Raph Koster's Blog, page 25

January 25, 2012

Fun vs features

You have a system. Let's say it's a system where you can throw darts. And you have to open your bar in one week.

Throwing darts might have a bad interface. The dartboard might be too small or too big or poorly lit. Darts may be a perfectly nice idea, but the implementation of it needs tuning.

At this point, you have a feature, but not fun. It's gonna take you four days to make it fun.

You can refine darts, get it fun. Make the UI good, have a great physics model and control, great graphics, and in general, you can get it to where you have a fun feature.

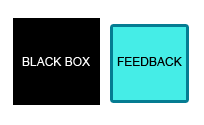

The exercise here is going to be threefold: making sure the inputs afforded to the user map well to their view of the "black box" that is the darts system; making sure the darts system itself offers interesting repeatable challenges; and making sure that the feedback from the black box Is both juicy and educational, so that the user can get better at darts. All this is hard.

Then you face a choice. Three days left, if you made darts fun. You can either go implement a pool table, or you can add content to darts. Content would be new kinds of darts, more kinds of dart games, etc. They don't call for a new system, just other kinds of data. Not much new code (and new code runs the risk of introducing bugs). You can make the best darn darts game in the country if you spent the three days on that.

The pool table, you could get that in instead. But what if it's not fun on the first try, just like darts weren't? Then you'd have a decent darts game and a crappy pool table.

Which is better, having the best darts game available, or having a middling darts game and a bad game of pool?

Adding features offers the potential for fun, but fun comes from tuning and balancing. It isn't magically there just because you got a pool table.

In order, I would have to tackle the black box, then the inputs, and finally the feedback. I can't make a bad system much better with great affordances and while I can make it juicy, it usually won't hold players.

I would choose to polish up darts, and promise to get a pool table in there as soon as I can. And when I do put in the pool table, it'll be as good a game of pool as we can make rather than being rushed to fit in before the bar opens.

This isn't the answer I would always have chosen in my career. I have done plenty of kitchen sink design. I have also settled for poor affordances and feedback far too often. I have even had perfectly wonderful systems be unusable because we could not figure out a way to make the feedback comprehensible.

I've always leaned towards elegant systems, meaning ones with few variables and few rules to them. When you populate a game with many of these, they very frequently end up leading to emergent behavior, which can be quite fun. But when you lean on the creation of simple systems, the temptation is even greater to have lots of them in your game. And that can and will lead to most or all of them feeling unpolished and unfinished.

I've gotten good enough at coming up with simple rule solutions that gosh, almost 10% of them work on the first try! (Yes, read that as sarcasm aimed at myself). But these days, I tend to assume that it will take me ten times longer to polish up and tune that rule system than it will to come up with the rules in the first place.

January 24, 2012

An atomic theory of fun game design

This is the original essay in which I worked out the basics of my game grammar approach. It later became a GDC talk. This essay was written in 2004, and the genesis of it was working through issues with the crafting system in Everquest II with Rod Humble. This essay no longer represents my current understanding of game grammar, but it's a decent start.

This essay has never been publicly posted (it was originally posted only to a private game developer forum, on June 26th of 2004), but I thought I should make it available both for historical interest and also for the sake of clarifying some of the things that I now take for granted when I discuss game design here on the blog. I can't expect everyone to have read everything I have ever written, of course, and in this case it's even worse since some of the material was only delivered at conferences. So many of the responses to the article on narrative were clearly from folks unaware of some of this work that it felt like the right time to post it up.

Since this was written, I have met fellow travelers — boy, was I pissed when Dan Cook's "Chemistry" article came out a few years later, and had such nicer diagrams! I also found Ben Cousins' work on "ludemes" later, a term I gladly stole. And I think this served as some inspiration to folks like Stéphane Bura and Joris Dormans who have pushed this in fresh directions I would never have pursued. There have been grammarian get-togethers, Project Horseshoe whitepapers, and more. I even have a pile of blog posts that fit under the "game grammar" tag here on this site for those who are curious about more.

Lately, I've been spending a lot of time thinking about the nature of fun. I've reduced it down to a cognitive challenge, the notion that fun is the feeling you get when you are exercising your brain by solving a cognitive puzzle. Sometimes the puzzle is provided by a computer, sometimes by another player, but either way, your brain is basically trying to perceive a pattern; victory usually comes from identifying the pattern, then correctly executing on some action that the pattern does not account for. For further thoughts on this and its implications for game design as an art form, I refer you to my presentation "A Theory of Fun."

This suggests that there are probably ways to break down or otherwise analyze what makes a given puzzle or challenge fun. Now, challenges or puzzles come in a very wide array of forms—spatio-temporal challenges like Tetris, and physical dexterity ones like soccer. What do all of these have in common?

Building a subgame atom

The following algorithm came about from attempting to map the basic features of MMOG combat systems onto MMOG tradeskills, which are usually regarded as not having met a sufficiently high bar of fun. Interestingly, MMO combat itself is often not regarded as having reached that bar either, and yet it succeeds in keeping players captivated for many months on end, when correctly executed.

A successful MMO probably needs to have many individual subgames (of which combat may be one) in order to be successful, and for maximum impact, each of them needs to fulfill all of the following requirements. In fact the atom needs to have certain known "system inputs" and "system outputs" so that it can be hooked together to build game "molecules" if you like.

We typically refer to each atom as being "a game system" in game design, but part of the point of this essay is to show that this definition is to a degree recursive. Once you have knitted together several atoms into a molecule, the molecule as a whole must also meet all the criteria for what makes an atom fun. When looking at a piece of interactive entertainment, it is made out of at least one atom, and possibly many molecules, as in the case of MMOGs. In the end, what we refer to as "scope of a game" is really measure of how many atoms it has.

Taking the MMOG combat example

I've selected hack 'n' slash MMO combat for my example, because it is a well-established mechanic that has undergone twenty years of refinement; it is a multiplayer mechanic, which brings in additional wrinkles for cooperative games that would otherwise be absent from the model; it can be performed either against computer opponents or other players; and it is typically not a full game in itself, but is one system among several in the MMO, thus demonstrating the recursive and connective qualities of game atoms.

When you break down what makes MMOG combat entertaining, there turn out to be a surprising number of required elements:

Preparation is required. In most cases, this may be as simple as healing up before entering the encounter. At its best, there is an opportunity here for hooking the combat system into the larger network of subgames via the need for non-combat roles. At a minimum, different forms of preparation should be viable, in order to provide different tactical choices.Important point: preparation cannot be allowed to overwhelm skill. In fact, in a game that is a pure test of skill, you may not have variable preparation. It's worth noting that when this is the case, advanced players will often come to the challenge less prepared on purpose, such as playing DDR backwards, handicapping yourself in chess, or playing Diablo in hardcore mode.A sense of place is required. Physical location affects tactics during the encounter, and affects the strategy of which locations to have encounters in. In other words, locations affect risk and reward.Important point: it's easy to have locations that turn out not to matter, in which case this becomes merely tedious. When they do matter, however, they add immensely.A solid core mechanic. This is in the nature of a puzzle to solve—it's a ruleset into which content can be poured, that is intrinsically interesting. Effectively, this core mechanic may be an entire atom in itself.Important point: Note that by itself, it is probably interesting only for a limited amount of time.A range of challenges. This is content; each enemy provides a unique puzzle. Combinations of enemies then provide additional puzzle types as well.Important point: whenever you reach the point where fighting the new enemy can be done using the same tactics as the previous enemy, you have not actually added a new challenge to the game. This is where players find repetition.A range of abilities required to solve the encounter. We design our encounters such that it takes teamwork to resolve them, via formally preventing any given character from having all the abilities required. Even in single-player games, however, the player who relies on a single ability usually ends up unable to compete at higher levels.Important point: Usually this starts out not being present at the lowest challenge encounters, and rises in necessity as you reach more complex encounters.Skill in using the abilities is required. Bad choices lead to failure in the encounter. This skill can be of any sort, really: resource management during the encounter, failures in timing, failures in physical dexterity, failures to monitor all the variables that are in motion.Important point: This says nothing about the level of preparation in advance of the fight, which leaves out the issue of skill entirely. It should be possible for a skilled and a non-skilled player to have radically different experiences, all other things being the same. Otherwise, players will rightfully say that they could automate the fight.A variable feedback system should be in place. The result of the encounter should not be completely predictable. Ideally, greater skill in completing the encounter should lead to better rewards, but some degree of variability in the reward is important to maintain interest and minimize "farming."Important point: you're playing with fire here, and if it makes you nervous, this is the only optional item on the list. Merely randomized drops is not sufficient, and it's incredibly easy to alienate players with long waits for what they want. The feedback should be such that it is always worthwhile, but perhaps not to you—or there should be a system whereby the feedback you get (e.g., the loot) is perhaps tailored to the way that the encounter was resolved. The reward should always be contextual to what the challenge was.The Mastery Problem must be dealt with. The system cannot permit high level players to derive maximum benefit from less challenging encounters, or you get bottomfeeding. This has the detrimental effect of also closing lower level players out from access to the content.Important point: the only effective way to do this is to forcibly make the lower level content no longer appeal to (or even be usable by!) higher level players.Failure has a cost. Loss of the given encounter or challenge ejects you completely from the atom, and pops you out of the stack. Next time you attempt the challenge, you are assumed to come into it from scratch.Important point: next time you come back, you may be differently prepared. The challenge you faced does not necessarily need to be reset to its original state, as "wear it down" is a viable approach to a given challenge. This leaves open the question of penalties for failure that extend beyond the individual challenge.Building an atom diagram

All of these things can be applied to any game system, but it requires approaching the issue theoretically. A simple list gives you this breakdown of required elements:

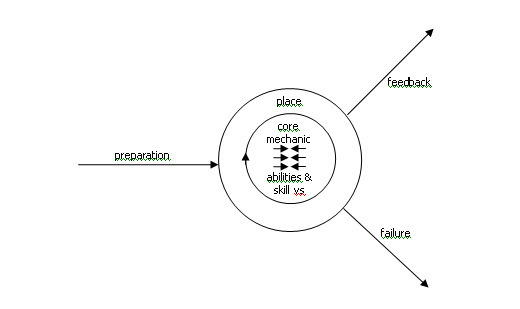

You can, using this atomic method, consider games as directed graphs of game atoms. A given atom looks like this:

In this diagram, you will notice that the abilities and skills are balanced—that is because otherwise, you get the Mastery Problem. The core itself then becomes a loop of repeatedly testing these abilities and skills against those of the challenge. It is worth pointing out that this entire core mechanic may well be composed of multiple atoms itself.

In terms of ludological theory, since atoms "stack," popping off the top of the stack effectively takes you out of the "magic circle" of privileged space.

You can then diagram games using this method, and see what the relationships are between game systems. Each input and output onto an atom can be linked to the input or output on another atom, and atoms can be nested within one another.

It's beyond the scope of this little essay to try diagramming an MMO, but even checkers provides an illustrative example.

The preparation step is generally skipped, since this is a two-player game. However, a typical form of prep would be to handicap one side or the other.The place is a fixed board, though interesting variant boards have been constructed using the exact same ruleset (CheckersFour being one such). The core mechanic of "checkers" is "capture all pieces." The range of challenges lies in different possible opponents. In that sense, you can consider checkers to be a "simple game" in that it is not a multi-stage experience. Most board games are not, but something like a puzzle game, which swaps out the space and perhaps the preparation on every level, certainly is. The range of abilities to solve this is very limited. You have pieces on the board. You can move them. You can jump with them. The skill lies in choosing which piece to move with. This part is in fact another game atom, because each move is a problem to solve itself: move, or jump? The variable feedback of winning the overall game of checkers is entirely driven by your emotional response and that of your opponent. The overall game of checkers does not attempt to solve the mastery problem via formal mechanics. If you come up against a toddler, you will win. This will make for a dull game for both of you. Because of this, we customarily avoid this sort of match-up. Failure to capture all the pieces results in loss. Next game, you have to start over from scratch, without any of the captures you achieved last game. All record of achievement is lost. Note that layering on something like a rating system or rankings or win-loss records actually nests the entire game of checkers as an atom within the "climb the ranking ladder" game.Now, nested within the game of checkers is another atom, that of moving a piece and attempting a capture.

The preparation step is actually that of the previous moves. The place is the specific tactical situation created by the previous moves. The core mechanic is "capture a piece." The challenge lies in the risk of capture of multiple of your pieces. Your range of abilities involve moving one piece diagonally. Depending on the game situation, that may be a king capture or a regular checker capture, and it might include multiple jumps. There is no skill required in this atom. This is an indicator that you cannot nest another atom within this one. It is a fundamental atomic unit of checkers.The variable feedback for success is interesting. There's the direct success of capturing one piece, there's extreme success of capturing multiple pieces via a chain of jumps, there's the orthogonal success of failing to capture a piece but instead creating a king, and there's the Pyrrhic victory of sacrificing a piece in order to create a better landscape in the next iteration of the atom. This variety is what makes checkers an interesting game. Removing one of these dynamics would make the game significantly poorer. Since there is no skill involved in the game of moving a single piece, there is no mastery problem. Failure ejects from the atom, and next turn you start on a new landscape that is worse off than the one you just left (because your opponent gets to move).Practical applications

All the above sounds very theoretical and useless. What happens when you walk through a crafting system using this? Let's look at what we do with tradeskills in most MMOs.

In the end…

A game diagram can be regarded as fractal. When you diagram your game, each possible skill choice will be an atom, and systems will be built out of linked and nested atoms. From far away, the whole game looks like one atom, one where the failure and success cases are both "game over."

If you have an atom that has a skill choice within it, and there's no atom nested within it, you're not done designing. If you have an atom that doesn't hit all nine elements, that atom probably won't be a fun game system, and needs to be redesigned.

Is this an algorithm for fun? No, but it's a useful tool for checking on the absence of fun, in that you can identify systems that fail to meet all the criteria. As such, it may prove useful in terms of game critique. Simply check each system against this list:

Do you have to prepare before taking on the challenge?Does the preparatory step pass this list as well?Can you prepare in different ways and still succeed?Does the environment in which the challenge takes place affect the challenge?Are there solid rules defined for the challenge you undertake?Can the one ruleset support multiple types of challenges?Can the player bring multiple abilities to bear on the challenge?At high levels of difficulty, does the player have to bring multiple abilities to bear on the challenge?Is there skill involved in using an ability? (If not, is this a fundamental "move" in the game?)Are there multiple success states to overcoming the challenge? (In other words, success should not have a single guaranteed result).Do advanced players not get a benefit from tackling easy challenges?Does failing at the challenge at the very least make you have to try again?If any of the above answers is "no," then the game system is probably worth re-addressing.

January 22, 2012

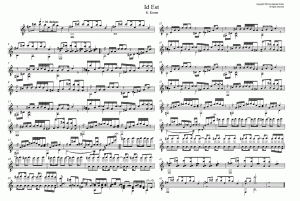

The Sunday Song: Id Est

On page 155 of Theory of Fun for Game Design there is some sheet music. It looks like this.

Click for full size

This is that song, played on solo acoustic guitar. Download audio file (IdEst.mp3)

– download

The song is played in DADGAE tuning, one of my favorite "weird" tunings — basically DADGAD with an added 2nd. As usual, I miked up like crazy: two condenser mics aimed at the guitar (one at the soundhole, the other at the 12th fret) plus a bigger diaphragm mic sitting a couple of feet away. I also used a pickup on this one, a Dean Markley Promag Grand.

I have the sound space set up a little weird… the ambient mic is "in the back," by applying a fair amount of reverb to it. It's panned around 36% to the right. The fretboard mic and the pickup and panned hard left and right, with much lighter reverb. And the soundhole mic is dead center, with a dry signal.

This has been knocking around the house since 2003, but I just got around to recording it right before the holidays. Enjoy!

January 20, 2012

Narrative is not a game mechanic

I love stories. My chief hobby is reading. I was formally trained as a writer, not as a game designer (there wasn't really any formal training for game design I got started, but that's another story). I think most game stories are not very good. And I quite enjoy games with narrative threads pulling me through them. When I find a game with a good story, I frequently prefer to the story to the actual game! So please keep that in mind as you read: I love story.

Narrative in a game is not a mechanic. It's a form of a feedback.

This simple fact is frequently ignored, particularly in games aimed at the mass market.

Let's start thinking about this by looking at what a game is. Games can and do exist without narrative. The core of a game is a problem to solve. As game grammar tells us, it's actually typically a series of nested problems: I need to reach this location, which means I need to defeat enemies, which means I need to traverse space, which means I need to mash a button. Some of these, like "defeat enemies," are complex problems in their own right. Some of them are trivial problems, such as "mash button."

Let's start thinking about this by looking at what a game is. Games can and do exist without narrative. The core of a game is a problem to solve. As game grammar tells us, it's actually typically a series of nested problems: I need to reach this location, which means I need to defeat enemies, which means I need to traverse space, which means I need to mash a button. Some of these, like "defeat enemies," are complex problems in their own right. Some of them are trivial problems, such as "mash button."

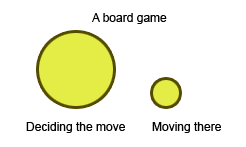

If you string these together, you'll typically find that the problems will alternate between abstract problems and simpler interface problems. For example, most turn-based board games alternate between the complex strategy problem of "what move to make next" and the simple interface problem of "pick up piece and move it here." Board games, of course, tend to be very forgiving regarding interface problems; if you drop the piece, nobody minds if you pick it up and put it where you meant.

If you string these together, you'll typically find that the problems will alternate between abstract problems and simpler interface problems. For example, most turn-based board games alternate between the complex strategy problem of "what move to make next" and the simple interface problem of "pick up piece and move it here." Board games, of course, tend to be very forgiving regarding interface problems; if you drop the piece, nobody minds if you pick it up and put it where you meant.

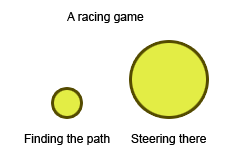

If you take something like a racing videogame, you now have a fairly hard interface problem; the sensitivity of the steering wheel or the analog stick is now an actual physical motor challenge — often a bigger challenge than the cognitive problem of where to point your car. Just turn on the "ideal path" feature that most racing games provide and you'll see that the challenge in the game as a whole tends to come from the dynamics of the controls and the black box of the performance characteristics of the car you have chosen.

If you take something like a racing videogame, you now have a fairly hard interface problem; the sensitivity of the steering wheel or the analog stick is now an actual physical motor challenge — often a bigger challenge than the cognitive problem of where to point your car. Just turn on the "ideal path" feature that most racing games provide and you'll see that the challenge in the game as a whole tends to come from the dynamics of the controls and the black box of the performance characteristics of the car you have chosen.

In a game grammar model, you always have a black box model, and you select something to input into the system. The system is going to give you feedback as to what effect resulted from your action. The game is in figuring out what the rules are for the black box. Not in a rigorous way, mind you — you tend to arrive instead at a mental model that gives you a heuristic as to how to approach the black box. Your learning is generally more intuitive — or even motor memory. It tends to function less at the logical level and more at the gestalt level (cf fluid versus crystallized intelligence).

The brain therefore tends to eventually dismiss whole classes of interface problems as trivial. "Click mouse" is one of these. "Mash button." Any black box which gets a heuristic of "guaranteed result" is going to make for a non-game very quickly.

The brain therefore tends to eventually dismiss whole classes of interface problems as trivial. "Click mouse" is one of these. "Mash button." Any black box which gets a heuristic of "guaranteed result" is going to make for a non-game very quickly.

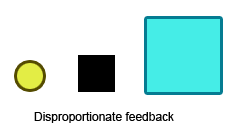

Ah, but the feedback for even a trivial action is very important. It matters that we hear the sound when we click the mouse. And should the designer choose, they can make the feedback be hugely disportionate to the problem solved. Feedback serves the purpose of cuing the user whether or not they are being successful in figuring out the black box. So we provide feedback each time an input is made, and the feedback is intended to help guide the user as to whether they are doing the right thing.

It is easy to see that if you remove any one of these things, you end up without a functioning game.

It is easy to see that if you remove any one of these things, you end up without a functioning game.

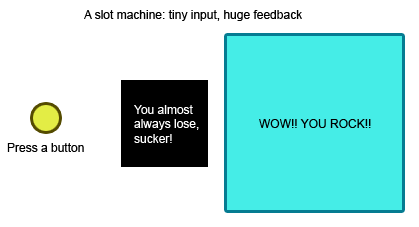

That said, the brain happens to loooove feedback. It triggers reward mechanisms in the brain. It is remarkably easy to trick the brain into thinking that it has accomplished something when it really has not. This can result in the player getting hooked on the feedback for a black box system that is actually remarkably simple — or even designed to not teach the player anything at all, as in gambling. In design, we often terms designs "juicy" when they provide plenty of rich feedback, but we sometimes call them "exploitative" when they simply abuse feedback to keep someone going.

That said, the brain happens to loooove feedback. It triggers reward mechanisms in the brain. It is remarkably easy to trick the brain into thinking that it has accomplished something when it really has not. This can result in the player getting hooked on the feedback for a black box system that is actually remarkably simple — or even designed to not teach the player anything at all, as in gambling. In design, we often terms designs "juicy" when they provide plenty of rich feedback, but we sometimes call them "exploitative" when they simply abuse feedback to keep someone going.

Games are a compound medium. They are made up of multiple other media, typically in the feedback. In other words, we rely on media such as film, writing, visual arts, music, and so on in order to provide the feedback. Games that do not rely on these other media much tend to get called "abstract" — a completely stripped bare game is actually a mathamatical diagram or formula, not something easily seen or cmprehended, so all games have to make use of other media at least a little.

Games are a compound medium. They are made up of multiple other media, typically in the feedback. In other words, we rely on media such as film, writing, visual arts, music, and so on in order to provide the feedback. Games that do not rely on these other media much tend to get called "abstract" — a completely stripped bare game is actually a mathamatical diagram or formula, not something easily seen or cmprehended, so all games have to make use of other media at least a little.

But these other media are of course very powerful in their own right, and each have their strengths. You can use music to convey emotion using elementary musical techniques. For music it's easy. Game systems can convey emotion as well, but for game systems it's hard, and near as we can tell, game systems also have a very limited emotional palette. So we not only use these other media to supplement the overall experience, but these other media can convey information that exists in complete parallel to the game system.

The commonest use of a completely parallel medium that does not actually interact with the game system is narrative.

The commonest use of a completely parallel medium that does not actually interact with the game system is narrative.

If we take the simplest form of "narrative game," the choose-your-own-adventure type of books, what we see is that the overall problem presented to the player, "get to a good ending," is fundamentally a decision tree, or directed graph in mathematical parlance. (Check out this link for a great giant diagram of one). So the initial problem is actually a decently substantial one — how do you get to a good ending, given that you have no picture whatsoever of the graph as a whole or even of what lies "behind the choice of doors"? Every page flip is a Lady or the Tiger sort of scenario.

What ends up influencing your choices is the feedback. Your first feedback comes from choosing to play at all: the first pages. This is exactly the same as giving you the starting layout of the pieces on a chessboard. From then on, each time you make a choice, narrative is used as the feedback mechanism to tell you whether a given choice makes sense or not in terms of leading you to your ultimate goal.

A bad example of these books would give you positive feedback all the way until it dumped you into a lava pit or other horrible doom. A good example would ensure that there was a rising action and feedback arc for each of the possible paths, leading to both a learning experience and a good story.

Side note: my favorite of these was actually one where you were trapped in a spaceship with nasty aliens, Inside UFO 54-40 . There was no path to the exit. You had to actually traverse the entire graph to realize this, and then when you got suspicious, identify the page that had no inbound link to it — whih then boldly celebrated your cleverness. The player's lesson learned is therefore quite profound: sometimes situations are set up not to be winnable, don't blindly obey the rules, and you should engage in lateral thinking when your survival is at stake.

Now I will pick on one of my absolute favorite games of the last year, Batman: Arkham City. There is a moment quite close to the beginning that has you climbing up a tower (spatial navigation puzzle with interface problems as well) only to reach the top of a cathedral where you are interrupted by a narrative moment: a video of the Joker playing on a television set, explaining that he has planted a bomb and you are about to die.

Now I will pick on one of my absolute favorite games of the last year, Batman: Arkham City. There is a moment quite close to the beginning that has you climbing up a tower (spatial navigation puzzle with interface problems as well) only to reach the top of a cathedral where you are interrupted by a narrative moment: a video of the Joker playing on a television set, explaining that he has planted a bomb and you are about to die.

AFter this long bit of rich narrative, you are presented with a very very small game. You have to rotate your camera to point at a window, and press the A button. If you do not do it within the time allotted, you die. If you succeed, you are treated to a gorgeous cinematic moment of leaping through shards of shattering glass and spreading your cape to a rigid wing, as you float away from a savagely exploding edifice in the midst of the brooding panorama view of Gotham.

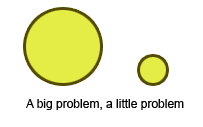

The diagram for this looks like a big pile of feedback followed by a tiny tiny problem, followed by another big pile of feedback.

This is a very common pattern in videogames these days. It even has a name: the quick time event. The black box is miniscule and simplistic. If we were to reduce the feedback, this "game system" would strike us as stupid. And it was stupidly simple in God of War, it was stupidly simple in Uncharted, etc. (Please note, I am naming some of my favorite games, made by collegeues and friends! Fortunately they, and Arkham City, offer plenty of rich systemic gameplay in between the movie bits.

This is a very common pattern in videogames these days. It even has a name: the quick time event. The black box is miniscule and simplistic. If we were to reduce the feedback, this "game system" would strike us as stupid. And it was stupidly simple in God of War, it was stupidly simple in Uncharted, etc. (Please note, I am naming some of my favorite games, made by collegeues and friends! Fortunately they, and Arkham City, offer plenty of rich systemic gameplay in between the movie bits.  ) It is almost, but not quite, as stupidly simple as the page flip in a Choose Your Own Adventure book.

) It is almost, but not quite, as stupidly simple as the page flip in a Choose Your Own Adventure book.

In fact, there was a quasi-parody series of games that basically took these sorts of supersimple game systems, and packaged them up with ridiculous feedback wrappers. It was called WarioWare. It derived all of its black box challenge from two factors: speed, and determining what the hell the confusing feedback meant. (The fun in the game was figuring out what stupidly simple action you were supposed to take).

There's nothing wrong, to my mind, with using narrative as feedback. But we have to keep in mind that all that narrative and visual content is the expensive part of making the game. It is also consumable, whereas a systemically driven game system can provide many many problems to solve and heuristics to develop (and therefore fun to be had), with relatively few rules. Because of this, narrative content is destined to be expensive, short, and over.

If you have built a game where your graph looks like this

And at the end of it you leave the player with "replay" that is nothing but this You're not going to get people to keep playing unless you keep releasing more content. This will matter quite a lot for any service-based game, be it MMO, F2P, social game, whatever.

You're not going to get people to keep playing unless you keep releasing more content. This will matter quite a lot for any service-based game, be it MMO, F2P, social game, whatever.

I also feel fairly comfortable in labelling a game with that sort of structure as "a bad game design" even if it may be a great game experience. The bar that designers should strike for should include a rich set of systemic problems precisely because that is what the medium of games brings to the table. It's what lies at the center of the art form.

If the systems of your game are outweighed by the feedback, you should grow suspicious. And if they are outweighed by feedback that takes the form of movies, you're making interactive movies first and games second.

January 19, 2012

The books I gifted in 2011

I gave a few books as gifts last year. These are the three non-fiction books I most often recommended to people. I ended up giving away multiple copies of these.

I gave a few books as gifts last year. These are the three non-fiction books I most often recommended to people. I ended up giving away multiple copies of these.

The thing they have in common: they all make you revise your view of the world.

1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created

It's sort of like Connections but for world history since that date, with a huge emphasis on the way globalization changed the world. One of the best moments is when he talks about plants… as American as apple pie (apples are from Kazakhstan); Italian food without tomatoes (they are from the Americas); the Irish and potatoes; southeast Asian cooking without chilies (from Mexico); Switzerland without chocolate (also Mexico); and rubber having basically moved from Latin America (where there's a native endemic pest that kills the trees) to Southeast Asia (where there isn't… but 40% of the world's rubber comes from those trees, we're utterly dependent on it for airplane tires, electrical wiring, and medical use; and we're just waiting for the moment when some idiot travels from Brazil to Indonesia with some mud on their shoe and kills the entire monoculture crop in Vietnam & South China.

I can't resist, even though it will bloat the blog post…

There's a chunk in there which explains how (if I can remember it correctly) the fact that Europeans were engaging in trade with Africa and got bitten by mosquitoes there meant that they became latent carriers of malaria… which then resulted in them getting bitten again by non-carrier mosquitoes in the tropics in Latin America, which resulted in the rapid spread of malaria to mosquitoes in the Americas, which meant that when silver was discovered in Potosi in Bolivia, or really riches anywhere, a malarial climate meant that the primary source of labor had to be imported from a population that carried a genetic resistance to malaria — namely West Africans; and this is why slavery never took strong hold in the territories outside of the anopheles mosquito's climate range.

Of course, the malarial areas in the Amazon meant that the silver could not be exported via the relatively short Amazon River route, and therefore had to be carried by llama to Peru, where it was shipped to the Philippines and to Spain; this is why there is such a substantial Asian population in Peru today.

This also led to the introduction of potatoes to Europe, which led to a massive rise in population, but since potatoes were cultivated via "clones" from only ten genetic lines, there was a massive monoculture which later led to the Irish famine. In Europe, it resulted in a massive financial crisis because of an excess of currency supply from all that silver in every nation in Europe, which led to dramatic inflation followed by the financial collapse of just about every monarchy on the Continent and the creation of a middle class.

Meanwhile, the reason there was an appetite for silver in the Philippines was because China had settled on silver (of which there are no significant local sources) as their currency, so they actually took something like half the silver from the Americas. In China, this ended up leading to a liquidity crisis when the mine in Potosi was exhausted which resulted in the Ming not being able to pay the troops for defense against the Manchu, so malaria indirectly caused the fall of the Ming dynasty. The Manchu then tried to exterminate the pirates who traded the silver with the Philippines, but couldn't quite because they were hooked on tobacco at this point (thanks to the Amazonian variety having been smuggled to Virginia). But they did get a lot of the pirates fleeing into the hills with sweet potatoes and maize, which resulted in the deforestation of the hillsides thereby destroying the incredibly intricate and careful Confucian-era water management schemes, which led to the epidemics of flooding that China saw until they initiated their modern dam projects.

I'm just scratching the surface — it's dense and intricate and in places nearly unbelievable. I loved it.

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood

It begins with African talking drums and the curious poetry they contain embedded in their beats, and from there embarks on a tour of all of information theory. We learn of entropy and Claude Shannon, of Babbage and Ada Lovelace, of the way that "a noisy line" is encoded into our very genome, of Maxwell's Demon and the telegraph and even a small bit of number theory. And it goes further, into quantum computation, tracing the way in which you can regard just about everything — the physical world itself — as information, data to be parsed and represented, in more and less accurate ways.

It does contain an excellent overview of information theory itself, but more importantly, it is a cultural history of information itself, how it spread and was conveyed. As this is the great cultural tide of our time since Gutenberg (and indeed, the book culminates with talk of Twitter), it resets yor entire view of what culture is and means.

I was struck by the chapters getting across the great shift we have undergone, from information's scarcity to today's utter overload — by the example given of Beethoven not knowing Bach's music, while today we know it all. For me this rings true in the way in which all styles of music seem to be popular at once these days, with top hits featuring banjos and swing jazz and Motown and Delta blues all mashed together. With everything at your fingertips, even the context of why they might fit together is yet more information, and today's child grows up in a world in which everything in the past is still the right now, because you can no longer even tell the dustier facts by their presence in dustier pages. In music, this leads to the Amy Winehouses and Adeles, who may as well have been born a few decades too late. In games, it is the 15 year old NES aficionado (my own son loves to talk about his collection of original Gameboy games… a platform that died while his mother and I were still dating).

The power of this book is also in drawing connections, connections between means of communication and the underlying math of communication itself. Through the course of the book we come to understand why computing is the way it is, and also, most critically, that information is not meaning. It ends on a note of awkward transcendence:

We are all patrons of the Library of Babel now, and we are the librarians…

The library will endure; it is the universe… We walk the corridors, searching the shelves and rearranging them, looking for lines of meaning amid leagues of cacophony and incoherence… every so often glimpsing mirrors, in which we may recognize creatures of the information.

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You

The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You

The third book essentially takes the above two and applies them to the present moment. If virtual cultures are a new form of globalization that basically threaten the very notion of the nation-state; and if they, as virtualities, are premised entirely on the concepts of information and information theory, well, then, that means that we are not only at the verge of a Panopticon but also in the curious place where there are people who control those mirrors, and decide what we know about ourselves.

In short, this book is about the fact that we have set up our digital world to lie to ourselves. Repeatedly. We have built it, step by step, to confirm our biases and to never show us anything that troubles our placidity.

This is not a new thing; our buttons have always been pushed by media in whatever way earned media the most money. Well, these days our "libraries" — meaning, our search engines — and our "newspapers" — meaning the blogs we read — are tailored to us. The example I typically give of this phenomenon is what happens when you log out of Google (which I know, you never do!), and then search for "abortion."

Google takes your IP address, the ZIP code it gets as a result, the sum of all the cookies it might have, and figures out whether you'd rather see Planned Parenthood or a right-to-life website as your top result. If you're logged in and you have a Google+ profile, it'll be the first result on a vanity search. The circulars you get, the identity files that companies maintain about you and sell to third parties… the ads that follow you from site to site to site… and yes, the news you get and the (certainly false) picture of the world you get, built to show you only what you would normally be shown.

Personalization services give you what they think you want, you see. And you are tracked and dissected and bucketed quite a lot. But there's no filter for "I like variety" or "I like surprises" or "I like things I didn't know I liked." That's why most citizens of the United States think that they know about the world, when in fact the world's news almost never makes it past the borders. It's how China maintains a great firewall, and how there could be thousands of North Koreans gathered to mourn the man who essentially built an alternate reality for an entire nation.

I love it that say, Amazon knows what books I have bought and liked and therefore offers up apropos selections for further reading. But the long-term result, which we see manifested clear as day, is that Republicans do not read books by Democrats, and vice versa. It is that millions of people who Tweeted yesterday saying "What is SOPA or PIPA and why is Wikipedia dark?" The information, it is out there. But it always reflects us right back to ourselves… well, that and a suitable, well-targeted banner ad.

We can go back to 1493 to see the long-term results of this sort of short-sighted thinking. "Recommended for You" is the cultural equivalent of China's blindness with the Potosi silver mines.

Taken together, these three books give much to ponder. I can't recommend them enough.

January 17, 2012

Commodifying culture

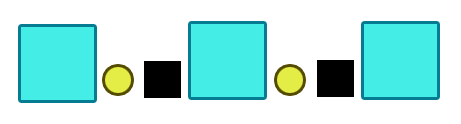

Feast your eyes on the book porn to the left.

Feast your eyes on the book porn to the left.

Go ahead, click on it and get the larger picture.

Gorgeous, aren't they? They're the complete set of the D'Artagnan Romances by Alexandre Dumas: The Three Musketeers, Twenty Years After, and the three volumes of The Viscomte of Bragelonne,the final volume of which is generally better known as The Man in the Iron Mask.

They were published by Thomas Y. Crowell Co., no longer extant as such, in 1901. Not first editions — that would look like this – but glorious nonetheless. Gilt on the edging, inlaid on the relief covers, onionskin endpapers in front of every engraved illustration…

Nice enough that you can still buy an facsimile of this exact edition, alas without the rich red covers and with something fairly hideous on the cover instead.

They're something to hold, to examine. Maybe not to read. Defintely something to have visible on a shelf where people can ooh and aah. They were given to me by my uncle for Christmas this year.

I have more than a few other books like that. I've got a hardcover American edition of the first Harry Potter, signed by Jo Rowling, made out to my daughter with a personalized message. A bunch of old books, a lot of autographed SF novels written by people I know, some of whom are pretty well known: Brin, Sterling, Doctorow.

I have a lot of the same books as epubs on my iPad. And it's qualitatively different. The e-books are commodities, and if one get deleted, I won't have any regrets. Whereas if my complete run of first printings of the Doonesbury compilations (even including the obscure one for the TV special!) were to get lost or damaged, I'd be quite upset.

There is a fetishistic quality to the physical object, a quality that means that I will probably never have a house without books. In fact, now that we have a larger house with bookshelf space, we have carefully placed 4×4 beams towards the back of every shelf so we can double-stack the books and still see every spine (a trick I recommend! Buys you two additional shelves of books per bookcase).

There is a fetishistic quality to the physical object, a quality that means that I will probably never have a house without books. In fact, now that we have a larger house with bookshelf space, we have carefully placed 4×4 beams towards the back of every shelf so we can double-stack the books and still see every spine (a trick I recommend! Buys you two additional shelves of books per bookcase).

Oh, there's a lot of books that probably I don't need and will never read again. But I carefully gather up and keep in order every Ian Rankin mystery novel, every volume of Transmetropolitan, each of the slender paperbacks of Mafalda in the original Spanish. And I make sure they can be seen.

Signaling theory is a small branch of cognitive science which argues that quite a lot of the things we do are intended as signals to third parties — especially prospective mates — about our status and interests. I think of what we do at our house with books as being basically that: a sign of who we are. We're just not the types of people who will ever live without physical books, because electronic copies aren't visible, and aren't valuable.

There is an implicit valuation of cultural objects based on physicality — indeed, implicit calculation of actual monetary value. Rarity matters — whether it's the fact that one of my two copies of M.U.L.E. is still in its original shrink-wrap (the Commodore 64 one, not the Atari 8-bit one — I played the heck out of that one!) or the fact that my print of the goblin market from Stardust is signed by Charles Vess.

In fact, I am having great trouble keeping myself back from boasting about even more of my geek possessions as I write this. I am engaging in signaling to you about what matters to me.

It's gotten a lot harder to signal music. It's everywhere. The rarity and the scarcity is gone. Some music geeks are working hard to bring it back, by putting out vinyl limited editions, precisely because the physicality of the vinyl format, with its generous cover sizes, the patina of survival, the whiff of authenticity from when music seemed (I do say "seemed") less commercial, all seem like the qualities that bring back that fetishistic element. People don't collect the MP3s of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band for the intact cut-outs in the album sleeve (that my vinyl copy from the 60s has, neener neener).

All culture, though, is becoming commodified. And cheapened — I mean that literally, cheapened on the open market. The benefits are enormous:

Even as pro-level content has gotten dramatically more expensive to produce, we have seen the quality of amateur content explode. Now there are Beatles in living rooms everywhere. Far far more people have turned out to have talent than I think was ever evident in all of history.Creative output can be shared fairly trivially, enabling people who have never before had access to libraries' worth of information to learn about darn near anything. Just tonight by daughter was complaining about her biology teacher, and I said that in this world, there's no excuse… just go find another bio teacher at bioteachershangouthere.com. Which may not exist, but should. The point being that where information was scarce, it is now more like air. Polluted, but everywhere.We live in an age where people are sagely telling us to move into tiny houses and get rid of the accoutrements of consumerism. An implicit message is that we should not be valuing many of the things we value nearly as much as we do. After all, is the value of The Three Musketeers in the binding or the text?

Bizarrely, I think for me, at least right now, it's in the binding. Content is ever more ubiquitous. Containers are what has grown rare and precious.

I think of this now with our increasingly digital medium of games. I have a 60s edition of Risk, alongside a modern one. I have a handmade Nine Men's Morris, a Lord of the Rings chess set. I have a MAME cabinet, and I can play Centipede with a trackball, dammit. And I still keep the cases of Playstation 1 games that I have not bothered to boot up in many years. But in not too distant a future, I'll probably be paying quite a lot extra to have a physical object to fetishize and show off my devotion to my craft and hobby.

Someday, when everyone gets to carry around the complete works of humanity on a cufflink, it's going to be interesting to see how we tell each other who we are.

January 16, 2012

Blog hosting upgrade

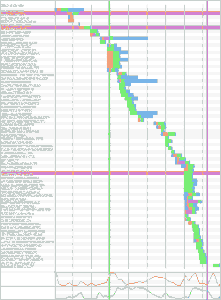

WebPageTest waterfall of page loading here

I just upgraded my hosting plan, and we'll see if that solves issues with the site performance. In addition to everything I mentioned in my last post, I also took some additional steps to improve performance, captured here for the sake of anyone else who has issues.

I fired off an email to the maker of Category Icons, which seems to be one of the common slow queries. For a while today I had it disabled outright, but I seem to have more headroom on this new hosting plan, so the icons are back.I found that wp-cron.php, which is what the blog uses for scheduling posts and other cleanup tasks, was generating a lot of hits — as in, a quarter million this month alone, far outweighing most of the blog traffic! This appears to be a common problem. I followed the advice found here on how to disable WordPress' built-in cron stuff and instead use a regular cron job. We'll see how that does and whether everything works more or less like before.I found that the Exploit Scanner plugin, which I have mentioned on the blog here before, was a huge culprit in adding cruft to the wp_options table. I suspect that a few scans simply failed to complete — heck, I cancelled one the other day because it was taking too long — and left the entire state of the scan in the table. There were only two of these, but removing them reduced the table from 8.4MB to 99.2k. Yes, you're reading that right. With that, my slow queries checking the wp_options table went away.While I was at it, I also went through the table and cleaned out obsolete options. Clean Options was helpful in this regard.Running tests with Webpagetest.org, I found that there were still some pesky files that were not getting compressed. So I added this to my .htaccess file to try to catch everything:# BEGIN deflating

AddOutputFilterByType DEFLATE text/html text/plain text/javascript

# END deflating

After doing all that, the site was still dog slow, and Nick, the support guy at BlueHost who helped me out, spent 45 minutes with me trying to figure out what else it could be before we arrived at the conclusion that I had simply outgrown their basic hosting plan. In the last couple of weeks I have been averaging 4000-8000 hits an hour, thanks to the controversies around free-to-play and immersion and thanks to Hackner News, BoingBoing, and Massively… So I upgraded, and now getting the site — even non-cached, the way I see it as an admin — is ten times faster than just getting the first byte was earlier today. Almost all readers will be getting cached pages, so it should be even faster for them.

This post itself should serve as a decent test of how well all this worked!

Sometime soon I will also be taking advantage of the dedicated IP that comes with this hosting, which might help a tiny bit more… but it will result in the site being hard to reach for a while as DNS records update, so I'm going to let it ride for now.

Speeding up the blog

As you may have noticed if you have been visiting the site lately, it's been both running very slow and also periodically giving lots of database errors ("error establishing a database connection"). So tonight I did a bunch of stuff to try to speed it up; I have no idea if this is enough, but it should be better!

Here's the list:

Installed WP Minify.I had to specifically exclude audio-player.js so that the little music player would work when I post up a song.Installed WP Smush.itI ran the bulk smusher, but it started erroring on finding a bunch of older images, building a weird compound messed-up URL for them. Makes me wonder how many of those old images are even displaying in the blog…Reconfigured WP Super Cache. In particular:On the Preload tab, had it preload everything.I now use the mod_rewrite setting.I did install WP-Optimize, but I can't say that it helped very much. I had already gone into phpMyAdmin and optimized all the tables. But this will make it a lot easier to do.I went through the wp_options table and cleared out a pile of orphaned options that included the word "_transient." In theory these are supposed to get cleaned up, but it didn't look like they were. There were around 400 of them.I also installed Clean Options, to try to stay on top of this better.I switched Category Icons to to use one query for the icons, instead of one per icon. No idea if this helped, but I suppose it should.Disabled the Gravatars (sorry!)Changed all the little flags from the Global Translator plugin to use an image map. This was a setting in the plugin that I hadn't noticed, but it was a ton of individual image fetches before.Reduced all the theme's images by around 90%.Axed the "Get Firefox" button. Everything that reached out to Mozilla was slow.Axed the Google +1 button from the front page. Everything that reaches out to Google is slow. There are still a fair amount of other things that reach out there too.Axed the Facebook Like and Share buttons from the front page. Everything that reaches out to Facebook is also slow.Oh yeah, and that Recent Facebook Activity sidebar too.Switched from vanilla PHP5 to FastCGI. Not seeing any errors, so we'll see how it goes.Added static caching of images to my .htaccess file. I used this, which I found on the Net:ExpiresActive On

ExpiresDefault "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType image/gif "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType image/png "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType image/jpg "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType text/css "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType text/html "access plus 15 days"

ExpiresByType image/swf "access plus 15 days"

I do not expect this to fix everything. In running repeated tests on www.webpagetest.org, the commonest issue at this point is a slow first byte — sometimes up to 10 seconds. I assume that is an issue with my host BlueHost.com. Also, as I write this, I am getting occasional "Error establishing a database connection" messages anyway. So something is still up. But hopefully this is better anyway.

The slow query that seems to lead to the error is, alas, super-generic:

# Mon Jan 16 00:14:53 2012

# Query_time: 1.280560 Lock_time: 0.000000 Rows_sent: 0 Rows_examined: 0

use ;

SELECT option_name, option_value FROM wp_options WHERE autoload = 'yes'

This post itself is sort of a test… we'll see what happens!

January 14, 2012

FAQ on the immersion post

Yesterday's post on immersion has occasioned a fair amount of commentary and questions. More importantly, different people seem to have read the post in very different ways. Given its nature, and who I was speaking to with it, that doesn't really surprise me.

Rather than answer them in comment threads scattered all over the place, I thought I would do it all right here. So here is a FAQ!

Are you trolling? Please tell me you are trolling?

No, I wasn't trolling. It was heartfelt. It was also dashed off in the middle of a sleepless night. I did not expect quite the level of passion in reply, I have to admit.

Immersion is a slippery word. What did you actually mean?

I meant the sense of playing a game without ever getting its mechanics rubbed in your face. In the past I have said that there are two core abilities a designer needs to have: to be able to strip away all the surface and only see the math and systems; and to do the exact opposite, and only see the surfaces, the fantasy of it.

These are also two ways to play a game. You can come to it as purely a math puzzle to solve, or you can come at it as an experience. And ironically, with all the advances we have made in terms of presentation, it feels like more and more games are less about the experience and more about the acronyms and mechanics.

Wait a second! Don't you bemoan the overemphasis on narrative in games in other posts?

Yup, I absolutely do! I have been a big advocate for paying more attention to mechanics in game design, and less to trying to be movies.

The reason that I worry about the overly-narrative approach that today dominates the AAA game landscape is that players are almost entirely on rails, and you as a player mostly make only a few choices to surmount a fleeting intermediate little minigame obstacle (a given fight, in the midst of the plot).

It provides one sort of immersion — the one akin to what you get when you read a great book or watch a good movie. But to me games are not about having a story told to you, they are about forging your own path. A linear CGI movie with occasional puzzles to solve is a valid genre that I even enjoy, but it doesn't provide me any authorial agency as a player, and would often work better as just a book or movie.

I recognize that this is just me and my player type though.

Is this post about MMOs?

No, it wasn't actually. I have not been hooked on an MMO since Metaplace, and before that one, it was a few years as well.

No really, admit it, it's about SWTOR, isn't it?

I swear, SWTOR was not particularly on my mind. The post was prompted in part by hearing someone talk about Skyrim and how they stopped playing because they figured out how to max out some aspect of crafting and stacking bonuses or something.

I admit there was some minor lingering stuff from reading about SWTOR and seeing a review talk in terms of the number of blues, purples, and whatever other color items are color-coded with as "the way MMORPGs work." But I don't think of that as a SWTOR issue, I think of that as a fundamental yuck that all the big MMOs seem to be doing: throwing the mechanics in your face. I disliked "these are purples" in all the MMOs.

I know! This is about mobile gaming, isn't it?

Not exactly. I mentioned mobile but what I really was getting at is that as computing and therefore gaming grow more pervasive, they are going to inevitably push us to be gaming under circumstances where we will always be interrupted, always have "short sessions" unless we manage to explicitly lock everyone else out, always be connected. I have been predicting all of gaming moving to this mold for years now, and it feels to me like it's actually here now. And to me immersion takes time.

OK, then why did you write the post?

Because so many people clearly had immersion as an underlying complaint in their objections to my posts on free-to-play. Most specifically, people who had strong connections to specifically the MMOs I made, which were designed to be as immersive as I could make them.

F2P does throw the mechanics in your face, you see. It has tradeoffs. So I wanted to write some thing got across to those people specifically that I do feel their pain, and I do understand why they mourn and miss that quality as the business models and games change around them.

But Skyrim sold really well! Isn't immersion alive and well in high-end games?

No. High-end games in general are in trouble, actually. So picking out one game as your champion is not a great example when even five years ago you would have been able to pick out many.

Can't there just be a spread of games of different kinds, like happens in movies?

In books and in movies, tech has mostly stood still (barring 3d, a pro-immersion tool). Not so for games. In fact, games have the issue that as tech advances poor tech is actually anti-immersive for most people, so immersion constantly requires greater and greater investment.

Isn't this because developers are failing players and focusing too much on behaviorism?

I think that it is too facile to pin blame on anyone. There's a large confluence of factors here that affect the nature of games: how they make money, what the tech level is, how they are distributed, and who their audience is. Developers do indeed have to go where the money is, but the money is where the players are.

Are you saying that it is the player's fault?

No, not really, but the audience plays into it. The broader audience we have today unquestionably prefers to be led through an experience rather than discover their way through it. We invest far far more in cueing users than we used to. A game that does not provide constant feedback feels dull, because games have sort of become like "sugar rushes."

Is it generational?

Nah.

Isn't geek culture overtaking the world? And doesn't that help immersion?

It's overtaking the world in one sense, but so are reality TV shows.  And today's immersion in geek culture and fandoms is quite different in a lot of ways, because of its transmedia nature. It's adapted to be interruptible, in bits and pieces. It is also frequently designed to reveal how things work behind the curtain.

And today's immersion in geek culture and fandoms is quite different in a lot of ways, because of its transmedia nature. It's adapted to be interruptible, in bits and pieces. It is also frequently designed to reveal how things work behind the curtain.

Why have books not stopped being immersive?

Lots of books are not immersive, as was pointed out in the comments.

But just as a comparison, books went to blogs, and blogs went to tweets. Long form everything is suffering and/or evolving in this new technological world.

Are you depressed?

No; I am nostalgic for elements of how it used to be. But I am also tremendously excited by the design canvas that these changes have opened up. As I have said elsewhere, never before have we been able to design a multiplayer game for literally millions to play the same game. That's new, and unheard of. Never before have we had access to this kind of player, this mass market audience, and that opens whole new kinds of game mechanics and game designs. That is unheard of too.

Aren't you just being a crotchety old man about this? Look to the future!

I usually look too far into the future, actually.

I, and anyone, really, is entitled to miss something that they see themselves as losing, while also being excited about what is yet to come.

So are you saying developers should stop striving towards immersion?

Heck no.

Are games today less immersive, or is it harder for a professional designer to immerse?

It is always hard for a professional to immerse. These days, we're training the audience themselves to see under the curtain, so maybe it is just getting harder for everyone. That wouldn't make me miss it any less.

Are you "throwing in the towel" on immersion, as Massively put it?

Nope. Instead, I am pondering the ways to get the qualities I value into this new landscape.

That said, players do have this mistaken impression of me as solely a sandbox, anti-content designer. That's because most of them have only seen SWG and UO from me. People who played on LegendMUD remember me as someone whose content was particularly quest-heavy. People don't realize that I did a chunk of the writing on Untold Legends (the first one)… and that I have a background in fiction writing, so it's not that I am opposed to writing in games. And they also have never gotten to see the literally dozens of primarily system-driven boardgames and puzzle games I have designed over the years, the non-immersive MMO designs that never saw the light of day (yes, I have in fact designed pure hack n slash Diablo-esque MMOs… they sit in a filing cabinet at companies I no longer work for). I am not just a sandbox designer… it's just that's what people know me best as.

You like F2P, and now you say immersion is dead. Have you sold your soul? Given up on it and caved into what makes you the most money?

Ha ha ha ha. *wipes tear* No.

January 13, 2012

Is immersion a core game virtue?

"I feel a sense of loss over mystery… I feel a loss over immersion. I loved… playing long, intricate, complex, narrative-driven games, and I've drifted away from playing them, and the whole market has drifted away from playing them too," Koster says. "I think the trend lines are away from that kind of thing."

– Gamasutra interview of me by Leigh Alexander

Karateka

Games didn't start out immersive. Nobody was getting sucked into the world of Mancala or the intricate world building of Go. Oh, people could be mesmerized, certainly, or in a state of flow whilst playing. But they were not immersed in the sense of being transported to another world. For that we had books.

Even most video games were not like worlds I was transported to. Oh, I wondered what else existed in the world of Joust and felt the paranoia in Berzerk, but I never felt like I was visiting.

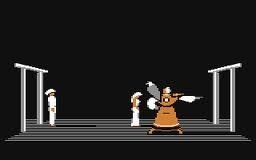

Then something changed. For me it started with text adventures and with early Ultimas. I could explore what felt like a real place. I could interact with it. I could affect it. And with that came the first times where I felt like I was visiting another world. It came when I first played Jordan Mechner's Karateka and for the first time ever, felt I was playing a game that felt like a movie.

I remember how we took that D&D Red Box Basic set and built a consensus world with it that ended up outweighing the rules to such a degree that we would often do role playing sessions for hours on end without any dice or books, just weaving our shared story together. We were sharing a dream.

For me, those dreams reached fruition with mud and then MMORPGs. Now other people were there too! And as a game designer, I focused pretty strongly on immersion as a core game virtue.

I wasn't alone. For others it came with the adrenaline of DOOM or the narrative of Half-Life, the world of Elder Scrolls or Wizardry or Fallout or whatever else.

Once upon a time, people actually dying on the field of play was an expected and normal part of sports. Whether it was a game of Aztec tlachtli or plain old rugby, it happened, and was considered an inevitable part of the sport.

Things that we once considered essential to games drift in and out of fashion. And I think immersion is one of those.

Immersion does not make a lot of sense in a mobile, interruptible world. It comes from spending hours at something. An the fact is that as games go mainstream, they are played in small bites far more often than they are played in long solo sessions. The market adapts — this reaches more people, so the budgets divert, the publishers' attention diverts, the developers' creative attention diverts.

As I watch my son and daughter play games or participate in role play sessions, I find myself reluctantly admitting to myself that it is a personality type that ends up immersed in this way, and were it not in games it would be in something else. Immersion isn't a mass market activity in that sense, because most people are comfortable being who they are and where they are. It's us crazy dreamers who are unmoored, and who always seek out secondary worlds.

It's just that games aren't just for crazy dreamers anymore.

Today even my immersive worlds have little XBLA pop-up alerts telling me that hey, someone just logged on and they want you to stop being Heothgar the Bold in Skyrim and instead come blow up some aliens on a party line while they made crude jokes in their actual voices and talk about how work went that day.

Even those immersive virtual worlds that I held so dear are full of acronyms and practices that strip away every shred of magic. PUGs and soul bound items and DPS counters and queues and level ranges and unlocking companions and cost for mounts and all that crap have very little to do with whether I dare cross the swaying rope bridge over the river, fearing that the rope may give way and leave me stranded on the side where the savage trolls are; very little to do with the moment of awe and fear that came from reaching out to grasp the crystalline diadem and pull it from the dusty cackling bones of the dead queen; very little to do with the twin moons over my head and the constellations made of the last gasps of stars whose light was quenched ten million years ago, when the universe was new.

It becomes an instrumental world, where the fantasy cannot live because it is always rudely awakening you to the fact that you are just at play, just playing a game, just pretending… And when we know we are pretending, well… The moment you realize it's all a dream is the moment you wake up.

I mourn. I mourn the gradual loss of deep immersion and the trappings of geekery that I love. I see the ways in which the worlds I once dove into headlong have become incredibly expensive endeavors, movies-with-button-presses far more invested in telling me their story, rather than letting me tell my own.

But stuff changes. Immersion is not a core game virtue. It was a style, one that has had an amazing run, and may continue to pop up from time to time the way that we still hear swing music in the occasional pop hit. It'll be available for us, the dreamers, as a niche product, perhaps higher priced, or in specialty shops. We'll understand how those crotchety old war gamers felt, finally.

The great opportunity ahead is to actually seize the moment at hand; to make games be the core entertainment medium of the century. We have always talked big about their potential.

Well, now we have the audience. We are starting to get the breadth of cultural reference, the emotional subtlety, the understanding of our craft, and the true diversity of core mechanics that opens up the broad audience, all of which enables us to fulfill that promise.

"Another way to think of it is, we always said games would be the art form of the 21st century: Gamers will all grow up and take over the world, and we're at that moment now," he continues. "It's all come true — but the dragons and the robots didn't come with us, they stayed behind."

I know many of you are frowning as you read this. The word of consolation is that said world with twin moons and stampeding herds of alien beasts, with derring-do and mystery, with the hours spent dreaming of its nooks and crannies — that world was always in your head, and not the screen.

Fewer games may be set there. And annoying alerts may pop up, and there may be a toll booth on the way to the dragon's peak.

But dreamers dream, and no one can take that away from us. Even if the light of the stars is quenched, that particular universe is always new.

Inspired by an interview given to Leigh Alexander at Gamasutra some time ago.