Raph Koster's Blog, page 24

March 13, 2012

"X" isn't a game!

I called this out as one of the trends I saw at GDC. Last year, people were saying that Farmville was not a game, and I argued that it was. This year, I wrote about narrative not being a mechanic and had to extend my comments on it because of the controversy, and Tadhg Kelly bluntly said "Dear Esther is not a game." At GDC, the rant session featured Manveer Heir saying that it was arrogant and exclusionary not to consider it a game, and arguing that the boundaries of "game" needed to be large and porous. Immediately after, Frank Lantz gave his own rant, which used sports extensively as examples of games.

The definition of game that most people — and I am particularly thinking here of the layman's use of the term — is basically something like "a form of play which has rules and a goal." Lots of practitioners and academics have tried pinning it down further. I've offered up my own in the past:

Playing a game is the act of solving statistically varied challenge situations presented by an opponent who may or may not be algorithmic within a framework that is a defined systemic model.

Some see this as a "fundamentalist" approach to the definition. But I use it precisely because it is inclusive. It admits of me turning a toy into a game by imposing my own challenge on it (such as a ball being a toy, but trying to catch it after bouncing it against the wall becoming a game with simple rules that I myself define). It admits of sports. It admits of those who turn interpersonal relationships, or the stock market, or anything else, into "a game."

Some see this as a "fundamentalist" approach to the definition. But I use it precisely because it is inclusive. It admits of me turning a toy into a game by imposing my own challenge on it (such as a ball being a toy, but trying to catch it after bouncing it against the wall becoming a game with simple rules that I myself define). It admits of sports. It admits of those who turn interpersonal relationships, or the stock market, or anything else, into "a game."

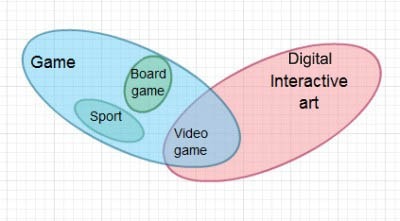

Basically, I see this whole issue as this Venn diagram. I group sports, boardgames, and yes, videogames under "game" because all of them are susceptible to being broken down and analyzed with game grammar. They all have rules. They all have an "opponent" that presents varied challenges to the player. They all have a feedback loop. They all present verbs to the player. They all present goals. The fact that some use real-world physics as the opponent, some use the human body, some use dice or boards, and some use a computer is not even relevant when you break down the game atoms. I can group these easily because I've dug into them so much that I know there is something there in common.

That isn't to say it isn't a very wide net — I wrote about games that fall on the boundary and seem lacking in goals altogether years ago, and still lumped them under game.

This doesn't mean I dislike all the huge potential that is in the other side of the diagram. On the contrary — Andean Bird began over on that side, and arguably was more successful there than as a game. And anyone who has followed what I've written over the last fifteen years knows that I believe that games can be art.

The question is whether that entire red area should have the name "videogame," which is what some are advocating. And I am resistant to that, in part because I suspect a Powerpoint slide deck could live over there. The unifying factor seems to simply be "displayed on a computer" to me. Mind you, I have great sympathy for the notion that a digital platform enables great new things for art! On the other hand, I also know that computers are not solely electronic, so even that boundary line feels a bit awkward.

So we could call all that stuff "game." Or alternatively, we need a name for what Dear Esther is, and that seems to me a simpler problem than renaming the category that encompasses baseball and tiddlywinks, which have both been called games for a very long time.

That said, I don't see any reason why that should be regarded as dismissive, exclusionary, or derogatory. Videogame designers have been crosspollinating with digital artists for a loooong time now — I think for example of Zach Simpson's work — and I think that the game developer community is certainly welcoming enough to things that live at the boundaries of either game or interactive art.

In short – there's no reason to call each other names. But naming things is still a valuable exercise, and I'd hate to lose precision on something that we are finally able to pin down.

March 12, 2012

My big GDC takeaways

Just some hastily scribbled notes here:

The art & the science are at least yelling at each other across a divide, if not talking.

Chris Crawford is more relevant than he has been in years. At least more discussed. People are now embracing things he said that they used to disdain. His face was put up on slides a bunch of times, and his spirit was invoked a lot. There were many calls for games to "grow up."

On the flip side, the social/F2P model is clearly not just winning but dominant — but there were a lot of discussions about how to do it ethically, rather than just rejecting it out of hand or embracing the monetization.

There's a little bit of an identity crisis. Some of this is from debates over terms ("is Dear Esther a game?" was a constant thread), which some feel to be exclusionary. Now that interactive art is burgeoning, it is either growing out of the rubric of "game" or expanding the definition. This is leading to people calling each other fundamentalist or clueless, which is not very productive.

In the process, that term definition exercise and the deeper analysis of the "science" of how games work has continued to make great strides, and many of the best talks were about understanding the audience psychology or understanding mechanics in greater depth. Game grammar-like diagrams popped up on many slides, and concrete game design exercises were showcased at great length — where we used to just get special-cases, we now get general principles.

A lot of the above was enabled by back-to-low-budget trends that enabled the indie and art game movements, and by the fact that mobile tech was easily accessible. The center of gravity has clearly shifted to mobile.

But there was also general agreement among business types that this Renaissance period is over. Budgets are about to skyrocket again, and we're now at the start of a "mature" period akin to the early glory days of consoles, or the early glory days of PC gaming. Expect creativity to give way to conservatism again and the stakes get higher in terms of budgets and time.

Basically, it feels to me like we're just about cresting the edge to a new plateau. We'll see what happens to disrupt this one.

March 9, 2012

GDC2012: Slides for Good, Bad, Great Design

Here's the PDF: Koster_Raph_GDC2012.pdf

Here's the PPTX, which includes the speaker notes, which this time are extensive: Koster_Raph_GDC2012.pptx

And the closest I can get to the speech itself is this page here, which has an image of each slide, followed by the notes… so you can just read it like an article.

I imagine video will be up on the GDCVault eventually…

March 1, 2012

GDC 2012: Good bad great design talk

I seem to have neglected to mention that I am speaking at GDC next week!

I'll be the last session of the Social and Online Games Summit, giving a quick half-hour session entitled "Good Design, Bad Design, Great Design" modelled after the blog post from a while back.

I'll be the last session of the Social and Online Games Summit, giving a quick half-hour session entitled "Good Design, Bad Design, Great Design" modelled after the blog post from a while back.

What makes a design good or bad? And more importantly, what makes it GREAT? And even more, does greatness even matter, when the goal is to make money? In this talk, industry veteran Raph Koster will look at an assortment of guidelines and aphorisms drawn from a variety of fields ranging from marketing to art theory, and see how they hold up. Raph will pay special attention to what they mean for the brave new world of social gaming. Hopefully you'll leave inspired.

Takeaway: Learn why it makes sound financial sense to reach for greatness in your work, and discover some of the science behind classic design principles from other fields.

If you're coming, see you Tuesday 5:05- 5:30 in Room 135, North Hall.

GGDC 2012: Good bad great design talk

I seem to have neglected to mention that I am speaking at GDC next week!

I'll be the last session of the Social and Online Games Summit, giving a quick half-hour session entitled "Good Design, Bad Design, Great Design" modelled after the blog post from a while back.

I'll be the last session of the Social and Online Games Summit, giving a quick half-hour session entitled "Good Design, Bad Design, Great Design" modelled after the blog post from a while back.

What makes a design good or bad? And more importantly, what makes it GREAT? And even more, does greatness even matter, when the goal is to make money? In this talk, industry veteran Raph Koster will look at an assortment of guidelines and aphorisms drawn from a variety of fields ranging from marketing to art theory, and see how they hold up. Raph will pay special attention to what they mean for the brave new world of social gaming. Hopefully you'll leave inspired.

Takeaway: Learn why it makes sound financial sense to reach for greatness in your work, and discover some of the science behind classic design principles from other fields.

If you're coming, see you Tuesday 5:05- 5:30 in Room 135, North Hall.

February 17, 2012

“Making of UO” articles at MMORPG.com

Read them here: Ultima Online UO General Article: The Making of a Classic Part 1 and part two.

I wasn’t able to really sit down with Adam Tingle, the author, but he did run around the blog archives a fair amount. There’s some inaccuracies here and there, but it’s a decent overview.

Throughout 1979 Garriott would design his computer role-playing game, revising it, adding to it, showing his friends, and finally when “D&D 28b” was finished, he renamed it Aklabeth…

It’s “Akalabeth” not “Aklabeth” — you can actually play it on your iOS device these days.

Together [Starr and Richard] started to knock ideas back and forth, based upon these new experiences, and came up with the premise of a multiplayer Ultima, or “Multima” as they affectionately termed it.

My understanding is that talk of “Multima” had been going on for quite some time, including discussions with Sierra (back when they ran the ImagiNation Network). This also leaves out the role of Ken Demarest, who was a moving force in getting the project started.

1996: So now that they had the art style, the funding, and the engine – they needed a direction for the game to head in…

Technically, we didn’t have the engine at the point the article states; the client was basically rewritten in 1995-96. Rick Delashmit had been there for a few months when my wife and I joined the project on Sept 1st 1995; other key early folks such as Scott “Grimli” Phillips and Edmond Meinfelder also joined in August to September of 95. That’s also around when Ken Demarest left, and Jim Greer — best known today for founding Kongregate.

I think I have told this story before, but the whole “dragons eating deer” example came from the design samples that my wife and I sent in as part of our job applications. We showed up on the first day and were taken aback when we were told that was how the game was going to work… So at least that much of the notion of “what the game was going to be” was set in 1995…

That crazy resource system stuff, particularly some of the AI, did in fact work in the alpha test. It led to rabbits that had levelled up and were capable of taking out wolves — or advanced players. We found this intensely amusing, and quoted Monty Python at each other whenever it came up.

Being as most of the team in charge of UO were coming from single-player games, with very few MUD veterans involved in the process…

This is just not really right. At least on the game dev team. From that September team, Kristen and Rick and I came from DikuMUDs. Edmond came from MUSH and MOO backgrounds. Scott and a tad later Jeff Posey came from LPMUDs. We had Andrew Morris, who was the original lead designer, who was a veteran of U7 and U8. And of course, our first artist, Micael Priest (most famous for his amazing poster art for bands in the 70s) wasn’t an online gamer either.

Later, as the team grew and absorbed a lot of folks from U9 (which was suspended for a while) there were plenty of non-online folks on the team. But the basic premises of UO were definitely set by folks from MUDs.

…the idea of GMs taking an active dynamic role, never materialised as initially intended…

The article says that the idea of having GMs take active roles in running events never panned out… but those who recall the Seer program and the many phenomenal live events that were run know that in fact, this did happen quite a lot.

By the time the alpha had ended, the Origin team had collected enough data, were able to fix bugs, glitches and exploits, and finally the home stretch was seen bobbing along the horizon…

This leaves out one dramatic and important step in UO’s history. The alpha was not an MMO in the “really massive” sense of the word. It supported the same sort of concurrency as Meridian 59 did — 250 or so. In between the alpha and the beta, the server was rewritten to allow for 2500-3000 concurrent players per shard. In order to do this, a whole bunch of new technology had to be invented for creating seamless borders between adjacent maps. These borders would prove to be a source of bugs for years (most dupe bugs made use of race conditions when moving across server lines).

Vogel would later admit “We were pressured on time. I wish we’d have had a little bit more time.”

All game dev teams say that, right?  In UO’s case, the time pressure was fairly extreme towards the end. After the huge reaction to the beta, all the eyes of the press were on us. A big meeting was scheduled to decide whether to ship — on a date that would make the all-important Christmas holiday sales. Nobody thought the game was ready to ship, but some higher-ups came around and helpfully told us that saying so in a meeting might be a career-limiting move. When the big “go-no-go” meeting was held, everyone voted yes except the QA guy.

In UO’s case, the time pressure was fairly extreme towards the end. After the huge reaction to the beta, all the eyes of the press were on us. A big meeting was scheduled to decide whether to ship — on a date that would make the all-important Christmas holiday sales. Nobody thought the game was ready to ship, but some higher-ups came around and helpfully told us that saying so in a meeting might be a career-limiting move. When the big “go-no-go” meeting was held, everyone voted yes except the QA guy.

All in all, if you go from when a team was put on the game (as opposed to just Rick & Starr), it was around Sept 95 to Sept 97 to make UO. Except that everything made up to the alpha test was thrown away and started over. So it’s really more like May 1996 to September 1997…

Vogel also often doesn’t get enough credit for putting in place all the vital things that simply were outside of the dev team’s scope, like, oh, billing and customer service.

Explaining events later, Rainz describes “I just cast the scroll on the bridge and waited to see what would happen. Someone made the comment ‘hehe nice try’, I expected to be struck down, instead I heard a loud death grunt as British slumped to his death”. Accidentally, this Internet consultant has just committed the most infamous act in gaming history.

I was busy coding something and missed this altogether. Scott rushed into my office and said “Did you see? They killed Lord British!” At first I wasn’t sure if he meant in the game or not…

Interestingly UO garnered an initial negative response from the press, Gamespot giving the game 49%

Both UO and SWG had the mixed blessing of being Coaster of the Year from Computer Gaming World… and also winning a variety of “best of” awards.

As time progressed Origin patched, refined, and grew the game in ways they saw fit, adding in a reputation system to calm down the rampant PKing

Somehow the article manages to then skip ahead to 1999, thereby missing out on discussing the great Trammel/Felucca split.

Anyway, a nice walk down memory lane, and perhaps the articles have stuff in them people have not heard before.

"Making of UO" articles at MMORPG.com

Read them here: Ultima Online UO General Article: The Making of a Classic Part 1 and part two.

I wasn't able to really sit down with Adam Tingle, the author, but he did run around the blog archives a fair amount. There's some inaccuracies here and there, but it's a decent overview.

Throughout 1979 Garriott would design his computer role-playing game, revising it, adding to it, showing his friends, and finally when "D&D 28b" was finished, he renamed it Aklabeth…

It's "Akalabeth" not "Aklabeth" — you can actually play it on your iOS device these days.

Together [Starr and Richard] started to knock ideas back and forth, based upon these new experiences, and came up with the premise of a multiplayer Ultima, or "Multima" as they affectionately termed it.

My understanding is that talk of "Multima" had been going on for quite some time, including discussions with Sierra (back when they ran the ImagiNation Network). This also leaves out the role of Ken Demarest, who was a moving force in getting the project started.

1996: So now that they had the art style, the funding, and the engine – they needed a direction for the game to head in…

Technically, we didn't have the engine at the point the article states; the client was basically rewritten in 1995-96. Rick Delashmit had been there for a few months when my wife and I joined the project on Sept 1st 1995; other key early folks such as Scott "Grimli" Phillips and Edmond Meinfelder also joined in August to September of 95. That's also around when Ken Demarest left, and Jim Greer — best known today for founding Kongregate.

I think I have told this story before, but the whole "dragons eating deer" example came from the design samples that my wife and I sent in as part of our job applications. We showed up on the first day and were taken aback when we were told that was how the game was going to work… So at least that much of the notion of "what the game was going to be" was set in 1995…

That crazy resource system stuff, particularly some of the AI, did in fact work in the alpha test. It led to rabbits that had levelled up and were capable of taking out wolves — or advanced players. We found this intensely amusing, and quoted Monty Python at each other whenever it came up.

Being as most of the team in charge of UO were coming from single-player games, with very few MUD veterans involved in the process…

This is just not really right. At least on the game dev team. From that September team, Kristen and Rick and I came from DikuMUDs. Edmond came from MUSH and MOO backgrounds. Scott and a tad later Jeff Posey came from LPMUDs. We had Andrew Morris, who was the original lead designer, who was a veteran of U7 and U8. And of course, our first artist, Micael Priest (most famous for his amazing poster art for bands in the 70s) wasn't an online gamer either.

Later, as the team grew and absorbed a lot of folks from U9 (which was suspended for a while) there were plenty of non-online folks on the team. But the basic premises of UO were definitely set by folks from MUDs.

…the idea of GMs taking an active dynamic role, never materialised as initially intended…

The article says that the idea of having GMs take active roles in running events never panned out… but those who recall the Seer program and the many phenomenal live events that were run know that in fact, this did happen quite a lot.

By the time the alpha had ended, the Origin team had collected enough data, were able to fix bugs, glitches and exploits, and finally the home stretch was seen bobbing along the horizon…

This leaves out one dramatic and important step in UO's history. The alpha was not an MMO in the "really massive" sense of the word. It supported the same sort of concurrency as Meridian 59 did — 250 or so. In between the alpha and the beta, the server was rewritten to allow for 2500-3000 concurrent players per shard. In order to do this, a whole bunch of new technology had to be invented for creating seamless borders between adjacent maps. These borders would prove to be a source of bugs for years (most dupe bugs made use of race conditions when moving across server lines).

Vogel would later admit "We were pressured on time. I wish we'd have had a little bit more time."

All game dev teams say that, right?  In UO's case, the time pressure was fairly extreme towards the end. After the huge reaction to the beta, all the eyes of the press were on us. A big meeting was scheduled to decide whether to ship — on a date that would make the all-important Christmas holiday sales. Nobody thought the game was ready to ship, but some higher-ups came around and helpfully told us that saying so in a meeting might be a career-limiting move. When the big "go-no-go" meeting was held, everyone voted yes except the QA guy.

In UO's case, the time pressure was fairly extreme towards the end. After the huge reaction to the beta, all the eyes of the press were on us. A big meeting was scheduled to decide whether to ship — on a date that would make the all-important Christmas holiday sales. Nobody thought the game was ready to ship, but some higher-ups came around and helpfully told us that saying so in a meeting might be a career-limiting move. When the big "go-no-go" meeting was held, everyone voted yes except the QA guy.

All in all, if you go from when a team was put on the game (as opposed to just Rick & Starr), it was around Sept 95 to Sept 97 to make UO. Except that everything made up to the alpha test was thrown away and started over. So it's really more like May 1996 to September 1997…

Vogel also often doesn't get enough credit for putting in place all the vital things that simply were outside of the dev team's scope, like, oh, billing and customer service.

Explaining events later, Rainz describes "I just cast the scroll on the bridge and waited to see what would happen. Someone made the comment 'hehe nice try', I expected to be struck down, instead I heard a loud death grunt as British slumped to his death". Accidentally, this Internet consultant has just committed the most infamous act in gaming history.

I was busy coding something and missed this altogether. Scott rushed into my office and said "Did you see? They killed Lord British!" At first I wasn't sure if he meant in the game or not…

Interestingly UO garnered an initial negative response from the press, Gamespot giving the game 49%

Both UO and SWG had the mixed blessing of being Coaster of the Year from Computer Gaming World… and also winning a variety of "best of" awards.

As time progressed Origin patched, refined, and grew the game in ways they saw fit, adding in a reputation system to calm down the rampant PKing

Somehow the article manages to then skip ahead to 1999, thereby missing out on discussing the great Trammel/Felucca split.

Anyway, a nice walk down memory lane, and perhaps the articles have stuff in them people have not heard before.

January 27, 2012

Awesome paper on games math

Giovanni Viglietta of the University of Pisa has posted up a paper called "Gaming is a hard job, but someone has to do it!".

Giovanni Viglietta of the University of Pisa has posted up a paper called "Gaming is a hard job, but someone has to do it!".

In it, he not only analyzes a variety games to determine their complexity class, but he also arrives at a few metatheorems that are generically applicable for all game design. In other words, "include these features and your game gains fun."

Remember, according to the Theory of Fun, pattern mastery and learning is why the brain plays games. And if you recall my presentation on Games Are Math, I made the case that entire classes of "tasty" problems can be described in mathematical terms (specifically, complexity class), because they are problems that always feel like they are on the margin of our ability.

So if you make use of these specific sorts of math problems — which are actually represented in the game as not looking like math at all, mind you — you are effectively inserting exactly the sort of problem that the brain finds most interesting.

These are not the only sort of problem the brain likes, of course — there ae psychological challenges, social challenges, physical challenges, emotional challenges, and so on. But an enormous amount of what we tend to call "gameplay" falls under the mathematical realm.

Among the metatheorems that Viglietti identifies:

Metatheorem 1. Any game exhibiting both location traversal and single-use paths is NP-hard.

Metatheorem 2. If a game features doors and pressure plates, and the avatar has to reach an exit location in order to win, then:

a) Even if no door can be closed by a pressure plate, and if the game is non-planar, then it is P-hard.

b) Even if no door is controlled by two pressure plates, the game is NP-hard.

c) If each door may be controlled by two pressure plates, then the game is PSPACE-hard.Metatheorem 3. If a game features doors and k-switches, and the avatar has to reach an exit location in order to win, then:

a) If k > 1 and the game is non-planar, then it is P-hard.

b) If k > 2, then the game is NP-hard.

c) If k > 3, then the game is PSPACE-hard.

Despite the jargon, these are immediately applicable to your games right now, and phrased in game terms are fairly simple features.

The paper goes on to provide proofs and examples for games ranging from Boulder Dash to Doom.

January 26, 2012

Narrative isn't usually content either

When I said that narrative was not a game mechanic, but rather a form of feedback, I was getting at the core point that chunks of story are generally doled out as a reward for accomplishing a particular task. And games fundamentally, are about completing tasks — reaching for goals, be they self-imposed (as in all the forms of free-form play or paideia, as Caillois put it in Man, Play and Games) or authorially imposed (or ludus). They are about problem-solving in the sense that hey are about cognitively mastering models of varying complexity.

When I said that narrative was not a game mechanic, but rather a form of feedback, I was getting at the core point that chunks of story are generally doled out as a reward for accomplishing a particular task. And games fundamentally, are about completing tasks — reaching for goals, be they self-imposed (as in all the forms of free-form play or paideia, as Caillois put it in Man, Play and Games) or authorially imposed (or ludus). They are about problem-solving in the sense that hey are about cognitively mastering models of varying complexity.

Some replies used the word "content" to describe the role that narrative plays. But I wouldn't use the word content to describe varying feedback.

In other words, perverse as it may sound, I wouldn't generally call chunks of story "game content." But I would sometimes, and I'll even offer up a game design here that does so.

The usual definition of "content" is "everything that isn't code or rules," meaning all the art and voiceovers and quests and whatnot. But that's not what it means in this context, because we're embarking on another one of thse annoyingly formalistic exercises here.

I have previously described the basic model I use for analyzing games formally as "a game grammar." This was mostly a conceit for a presentation title, but in point of fact it fits the formal definition of "grammar" moderately well. You see, this model, which I have also termed an atomic model of game design, is concerned exactly with the morphology of games: the structure and form they take. It builds on the seminal work of Chris Crawford, who defined interaction as

a cyclic process in which two actors alternately listen, think, and speak.

The game grammar model works the same way as all interaction does. The chief difference with game interaction is that one of those actors may actually be algorithmic: a computer, or a set of rules and processes. At core, a game is about figuring out the rules and processes that an opponent is using; said opponent might be a computer or a real person, or even the laws of physics and the physical constraints of your own body. Your job is to identify a goal (which might be handed to you by a designer, or might be one you set for yourself) and attempt to arrive at a way of interacting with this system that results in the outcome you want.

When we speak of a game system, that collection of rules is what we mean. Usually a system will be composed of multiple mechanics, each of which is made of up a variety of rules. A system like this has also been termed a "fun molecule," an "atom" or a "ludeme" by various authors.

A system, though, is sort of like an algorithm, or a printing press. It repeatably performs a process, but given different stuff to work with, you can get a pretty different experience out of it. The term for the "stuff to work with" is content, and most of the time it is effectively "statistical variation." An enemy with different stats, a level with different placement of platforms.

There is a class of games that focuses on user-generated narratives rather than on authorially imposed ones — you can read about the distinction in a very old talk called "Two Models for Narrative Worlds" I gave at the Annenberg Center at USC. In that talk I made the point that

These worlds can still tell stories. What we surrender is not narrative, but authorial control.

I coined the terms "impositional space" and "expressive space" to define the ends of this spectrum for myself.

Now, that talk long predates any of the game grammar sort of work. But effectively, my critique of quick-time-events and excess feedback used in narrative-driven games is primarily about impositional spaces, narrative imposed by the author(s) of the game; and it is essentially in a "ludic" context. And several folks took me to task for ignoring the expressive spaces and the spaces that are intended to serve as narrative generators in that critique.

Story, as it happens, has some rules too, largely based on how the brain works. For example, in The Art of Fiction John Gardner has a wonderful example of the ways in which repeated mention of physical objects causes them to become associated with emotions — in effect to become symbols. And then mention of objects associated with those objects does the same. In a sense, thematic freight becomes transitive.

Story, as it happens, has some rules too, largely based on how the brain works. For example, in The Art of Fiction John Gardner has a wonderful example of the ways in which repeated mention of physical objects causes them to become associated with emotions — in effect to become symbols. And then mention of objects associated with those objects does the same. In a sense, thematic freight becomes transitive.

That particular trick is used very very widely in all sorts of media. For example, Ravel's Bolero has become thoroughly associated with sex thanks to the film 10, and now at this point you can conjure up that association by just playing that music.

Expressive spaces in games rely on this trick extensively. In fact, all forms of post facto storytelling by players do. They ascribe meaning to moments, and then the player builds a narrative arc through their selective memory of events. I often call this mythmaking, and we do it pretty much all the time, without even thinking about it.

In games designed to cause the player to put together stories, such as Sleep is Death, Facade, or Dear Esther, there is a system there, an algorithm — and then there is the statistical variation that is fed into it. And that statistical variation, the content, is actually little symbols and narrative moments, ones that are often impressionistic or disconnected. The "problem" the player faces is that of arranging them into a coherent whole.

The fact that symbols and moments and memories are profoundly intangible things does not mean that they can't be manipulated in this way; fiction does so readily, as we have seen. From a mechanical point of view, though, they have much in common with the particular hand of cards you have been dealt, or the set of Scrabble tiles on your rack. You end your interaction with the system by making sense of them, which is different from finding a word in the tiles only by a matter of degree. Dear Esther's mechanics could be replicated with a different setting and group of symbols — to radically different emotional effect. When analyzed by the game grammar, we'd find two very different experiences to be the same game.

Let's consider a thought experiment.

I was once in a discussion with some fellow designers and one of them was playing with the idea of a game about memories. I offered up a design idea whereby there was a map of a house, and there was a deck of cards, each card labelled things like "comfy armchair" and "deep closet" and "empty bookshelf." The deck was shuffled, and some cards were laid in each room.

Players would then take turns tapping a card and telling a "memory" about that card and its place in that house. That this was the armchair where you remember curling up to read, a memory of safety and comfort; and another player says it was where they found great-grandmother when she finally passed away. All memories must be "true" — meaning, they cannot contradict anything anyone has said. After all stories were told, all the players decide which way they want to remember the armchair from among the stories told, by voting.

The person whose memory was selected keeps the card. At the end of the game, whoever has the most cards wins.

For greater emotional impact, you play this with real family, a real house layout, and real objects from your childhood.

Here we have both emergent consensus narrative and a game system. The memories are actually tokens in the game space — intangible ones, with a lot of emotional weight to them. You can approach the game mechanistically, and strategize. But you can also approach it experientially. It is mostly an expressive space. And ultimately, the real game lies in making sense of your family, its history. It is still pattern-matching, grokking each other and the complex web of relationships and half-truths and biased recollections that make up a family history.

In this game,

narrative is input — the affordance given to a player, the "move they can make"narrative is a resource — accumulated and managed towards a victory conditionnarrative is actually content, user-generated even, providing statistical variation into the systemnarrative is feedback — its accumulation, in the form of individual symbols, is representing the gestalt "game state"But it's still not a mechanic. You could in fact replace the memories with differently colored poker chips, and everything would proceed in the same manner. The experience would be substantially different, and the emotional impact far less.

You could also de-game this. Don't negotiate whose memories win out. Don't have the rule about non-contradiction. You'd end up with the experience of looking through a photo scrapbook — and likely, you would not tackle the challenge of understanding that the rules push you towards.

This game has never been played. If anyone ever does, let me know what happens.

In the post title I said that narrative isn't usually content. This game is an exception, as are the other ones I have cited. Ironically, games where narrative is content actually tend to have very very complex and robust rule systems. Chris Crawford's Storytron has years of development in it, almost all in the systems design. Facade is an AI wonderment. And even this little non-digital game has as "imported" rules a host of psychology and past family history, rules that are deeply perilous to transgress. (The mere addition of other players always imports complex social rules into a game; in this case, the deeply personal nature of the interaction brings in yet more. "We never talk about her drinking problem" and the like).

Because of this, I have no issue reconciling formalism in examining the "ludology" of games with the "narratological" approach of examining games-as-stories. My issues with small-system-big-feedback games described in the other post have to do with the lack of substantive pattern-learning, the lack of player agency, and thus the lack of the fundamental qualities that games bring to the table. And in that, I include emergent-narrative games and expressive spaces, which I certainly consider games — more complex games, in point of fact, than most games are. So for those who felt I was bashing the entire genre of emergent narrative games, I apologize for the lack of clarity there; that was not at all where I was going with that post.

So where does this all leave authorially imposed story? Primarily in the realm of interactive experience design. Which is a different discipline from "game design" though they have tremendous overlap. I am biased towards our getting game design right, but that does not mean that interactive experience design isn't a fascinating and deep area in its own right — or that it is unimportant to games. In fact, it's incredibly important. But that's a subject for another post someday.

January 25, 2012

HULKGAMECRIT and me

From Twitter and the hilarious HULKGAMECRIT.

HULKGAMECRIT: @raphkoster @ibogost @larsiusprime HULK WONDER WHAT FFEDBACK WOULD LOOK LIKE IF HYBRID GAME DESIGN & WRITER WERE TAKE CONTROL OF NARRATIVE!

Me: @HULKGAMECRIT There are a lot of those hybrids working. I'm one, trained as a writer, have MFA, do systems design & direct games too.

Me: @HULKGAMECRIT I think that means feedback would likely look much like it does today

HULKGAMECRIT: @raphkoster HMMM HULK SHALL THINK ON THIS…. HULK ALSO REALLY NEEDS TO PUBLISH MOSTLY FINISHED HULK ARTICLE ON JRPG DIALOUGE….

Me: @HULKGAMECRIT Hulk shouldn't think on it. Hulk should smash it.

HULKGAMECRIT: @raphkoster HULK DESIRE TO MAKE GAME INDUSTRY A STRONGER PLACE! THEREFORE HULK LAWS WERE ESTABLISHED TO SMASH ONLY WHAT NEEDS TO BE SMASHED!

@HULKGAMECRIT Feedback being the way it is may need smashed.

HULKGAMECRIT: @raphkoster EVEN THOUGH HULK IS GREEN AND SILLY…HULK SPENDS A LOT OF TIME THINKING! (HULK KNOW HULK IS WEIRD)

Me: @HULKGAMECRIT Never weird. Misunderstood

HULKGAMECRIT: @raphkoster

I guess it's not easy being green. Or gray, though I admit I never think of him that way.