Raph Koster's Blog, page 26

January 11, 2012

F2P vs subs

One of the comments on my recent posts accused me of being naive about marketing. That was a first for me.

A lot of commenters believe that free to play business models are fundamentally less ethical than other business models, that they are by nature predatory. So I thought I would offer up some simple facts.

The typical F2P player does indeed play for 100% free. It is not a nickel-and-dime model, as some commenters think. The vast majority of players in an F2P model never pay anything at all.

F2P players never end up paying $60 for a game they then find they dislike, as happens in the packaged goods world. In packaged goods, there are a lot of marketing practices designed to make you pick up and pay for something you do not want, often in large lump sums. (In grocery stores, it's making you move more slowly on the expensive aisles, by doing things like having smaller, bumpy tiles on the floor; in games, it is things like touched-up screenshots).

As a consequence, free to play is more democratic — more people can try a game, and this has opened up gaming to a huge audience that had never been in the hobby before.

That said, people playing for free are subsidized by those who pay — often quite a lot. These people only pay because they really want to, by and large, though of course, like any business, there are many tricks used in order to get people to convert to payers. But overall, a single-digit percentage of users are paying enough so that the average across all users including the free ones works out at something that is profitable.

Those who pay tons are termed "whales," which is a term borrowed from Vegas, and this is where people start to grow uncomfortable. But the fact is that whales existed in subscription and retail models too. They were the people who ran 10 to 30 subscription-based accounts — a phenomenon far more common than most players realize. They are also the people who buy the collector's edition of the game, all the novels, the figurines, the hint books, and fly to the convention every year.

It probably freaks all of us out that there are people who pay thousands of dollars a month for a game, until we realize that we probably all have hobbies where we would spend thousands of dollars, if we only could. Those who can afford it are very lucky… and if I could spend thousands of dollars a month on my hobbies (more musical instruments! more travel to exotic places! more books!) I have to admit I probably would.

Whales exist independently of the business model, and what free-to-play does is allow them to spend more on their hobby. Thus the free to play business model ends up monetizing core fans better while actually giving access to more players at the free-to-cheap end. Players whose price sensitivity was on the order of $5 instead of $15 get to play and pay what they want to pay, whereas in a subscription model, they were simply left at the door.

So in that sense, free to play is simply a more efficient means of getting the revenue. But in terms of a per-head revenue figure, it is dramatically worse than subscription model. The net effect of this is to make free-to-play businesses operate like retail stores, using as many tactics as they can to improve margins and maximize revenue. (I have often though that managing inventory for a grocery store would be the best possible training for running a social game in live operation).

Sub-based games and retail-based games also had their own library of tricks and tactics. I've never been contacted by a subscription based game saying "hey, we noticed you haven't actually logged on this month, so we went ahead and skipped billing you," just like I wouldn't expect a local gym to pass up dinging my credit card every month even though I don't go. Where sub games charged people for not playing, and retail games priced lousy games at the same price as good ones, free-to-play games charge you on the basis of upsells.

This works by making the base experience noticeably less attractive than the upsold experience: not very different from the gap between coach and business class on a plane, or between good and bad seat prices at a concert. But since a free-to-play player makes the purchase decision one purchase at a time, the base experience has to be good enough for them to consider paying at all. The moment the operator is perceived as overly grasping, the player can simply walk away or refuse to pay. That means you re-convert customers at every upsell, which is an inherent safety valve against abusive practices. Only happy customers are willing to pull out their wallets.

There are cases where this valve doesn't work — most people cite games such as ZT Online, which basically function like a casino. This drives people to keep playing using tactics that many find troublesome — myself included. But we've had an active debate going on for years whether MMOs by their very nature were headed down that slippery slope, and I believe that the fact that the discussion is ever-present is healthy for the industry. I would be far more worried if people took it for granted as standard operating procedure.

Game fans are also troubled by the injection of money into an equation that they are used to seeing depend largely on skill, particularly in competitive arenas. This is not a new debate — we have seen it in everything from sleeker swimsuit fabrics for competitive swimmers, to horse breeders with dough getting access to the right bloodlines, to salaries for Major League Baseball teams. It is not a new debate, and it happened just as much with the other business models as well, albeit in a more underground fashion.

People get creeped out by the science behind marketing. It's a lot more pervasive than people think, and an educated consume should definitely learn about it all and learn to recognize it. But there's nothing happening here that isn't already happening at your local market. If anything, expect that over time the science will be applied more and more to games regardless of business model. Social-game-style metrics are increasingly in use in console games, for example.

In the end, my message is this:

Free to play is not evil, it's just different. If you're freaked out by seeing business practices nakedly, realize that what's changed is that you can see them. And to my mind, that's actually better for you than blissful ignorance.

January 10, 2012

Product versus art

Yesterday, I posted about ways to improve free-to-play games, which got one commentator to say that I was comparing traditional designers to creationists, and free-to-play designers as evolutionists. A science versus religion debate, in other words.

Well, that was not really my intent. Let's say instead empiricists versus intuitionists.

That said, I think an important takeaway, which echoes my earlier post about dogma in programming approaches, is that taken to an extreme both approaches can be dangerous. After all, religion misapplied led to holy wars, and science misapplied led to eugenics.

The spectrum in the case of games might perhaps be seen as intuition leads to art, and empiricism leads to treating games as product.

Are either wrong?

Let's start thinking about this by considering the extremes. I've been promoting and defending the idea of games as art for a very long time now. But even in some of the oldest of those essays, I've argued against overly self-conscious, pretentious art:

…it's sort of fashionable to put down being artsy, these days. After all, the public's image of art is religious icons dipped in excrement*, it's tediously boring French films, it's dumping cases of type on a page and calling it poetry. These days, you can read about Art (with a capital A, of course) and substitute in this phrase: "pretentious, incomprehensible, shallow, manipulative, boring crap." Why sign up to defend something that has that rep?

Well, it's a valid rap. I have no tolerance for artsy crap. I find pretentious, overly craft-driven, self-referential, obscure, tangled, and weighty books to be garbage. Same for movies. I don't like most foreign films. I think it's the problem with poetry today. It's why jazz lost its audience. Why nobody cares who is writing the Great American Novel.

(*All apologies to Andres Serrano, because actually, Piss Christ is real art regardless of how provocative it is or disrespectful it is real art is often quite disrespectful!)

On the other hand, I've also at length made the case that taking the notion of product to an extreme is bad business, that in fact the right way to approach a customer base, particularly one you hope is a long-term one, is to woo them, romance them, and build a relationship.

The discomfort many have with free-to-play models, which they express with words like "soulless," is precisely that they see free-to-play as already having crossed the line to seeing games entirely as product. All you have to do is taken a look at the comment threads here, on Twitter, and on Google+ to see that.

The thing is, this is a spectrum, not a binary choice. Shakespeare wrote his plays to make money. Robert Heinlein, beloved of geeks, got started writing because he saw a chance to make $50 in a writing contest, and famously argued for rewriting little and keeping manuscripts in circulation until they sold. Dickens was paid by the word, and man, it shows. These ae all cases where we can say that art emerged anyway. But perhaps we should look at an example that is far more product-centric than that: the Stratemeyer Syndicate.

Edward Stratemeyer was absurdly prolific, creating piles of well-known children's book series: Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Bomba the Jungle Boy, Tom Swift… I could go on. And of these, his greatest creation was probably Nancy Drew, a titian-haired teenage girl detective who, along with her friends Bess (the "plump, timid one") and George ("the tomboyish one") and sometime boyfriend Ned Nickerson ("the fish's bicycle") solved mysteies in her native town of River Heights, and eventually all over the world.

Edward Stratemeyer was absurdly prolific, creating piles of well-known children's book series: Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, Bomba the Jungle Boy, Tom Swift… I could go on. And of these, his greatest creation was probably Nancy Drew, a titian-haired teenage girl detective who, along with her friends Bess (the "plump, timid one") and George ("the tomboyish one") and sometime boyfriend Ned Nickerson ("the fish's bicycle") solved mysteies in her native town of River Heights, and eventually all over the world.

Few would argue that the Stratemeyer Syndicate approached these works as product. (For a modern equivalent, we may perhaps look to James Patterson). Edward Stratemeyer's method was to write summaries of each book — outlines, and sometimes less — and farm these out to writers to actually write. They worked for hire, did not get authorship credit, and could be shuffled across multiple book lines. There was no single "Carolyn Keene."

Even further, once he passed away and the Syndicate was run by his daughter, the books were rewritten, sometimes mildly and sometimes with the entire plot discarded. The editing process here has gradually simplified the books, along with removing racism and period references. This has led to a thriving collectibles market for the original editions.

Nancy Drew changed with the times, and most argue, not for the better. You see, she was a perennial bestseller for literally multiple decades. She was born out of the early suffragettes, she became a feminist icon that inspired the likes of Gloria Steinem, she was put into a series of bad movies in multiple decades, was parodied, and in general had enormous cultural impact.

Many prominent and successful women cite Nancy Drew as an early formative influence whose character encouraged them to take on unconventional roles, including Supreme Court Justices Sandra Day O'Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and Sonia Sotomayor;[130] journalist Barbara Walters; singer Beverly Sills;[131] mystery authors Sara Paretsky and Nancy Pickard; scholar Carolyn Heilbrun; Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton; former First Lady Laura Bush;[10] and former president of the National Organization for Women Karen DeCrow.[132] Less prominent women also credit the character of Nancy Drew with helping them to become stronger women; when the first Nancy Drew conference was held, at the University of Iowa, in 1993, conference organizers received a flood of calls from women who "all had stories to tell about how instrumental Nancy had been in their lives, and about how she had inspired, comforted, entertained them through their childhoods, and, for a surprising number of women, well into adulthood."

In other words, Nancy Drew managed to do what we want from art.

It isn't really surprising though, to read a book like the truly excellent Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her by Melanie Rehak, and learn that really, the driving force behind Nancy was a woman named Mildred Wirt Benson, who managed to write the first Drew books many many of the later ones while coping with dying husbands, newborn babies, a thriving journalism career, and flying airplanes until she was in her 80s. She passed away an active working journalist at the age of 96. And even the person who edited the stories that many fans regard as having diluted the original conception of the character, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, was a suffragette when she was younger, a graduate of Wellesley, and managed to take over and successfully run her late father's business for decades and also raise a passel of kids.

It isn't really surprising though, to read a book like the truly excellent Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her by Melanie Rehak, and learn that really, the driving force behind Nancy was a woman named Mildred Wirt Benson, who managed to write the first Drew books many many of the later ones while coping with dying husbands, newborn babies, a thriving journalism career, and flying airplanes until she was in her 80s. She passed away an active working journalist at the age of 96. And even the person who edited the stories that many fans regard as having diluted the original conception of the character, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, was a suffragette when she was younger, a graduate of Wellesley, and managed to take over and successfully run her late father's business for decades and also raise a passel of kids.

It is undeniable that some of the qualities of these women's lives made it into the books, these books that were perhaps meant as mere product, books built to a very rigid formula of a fixed number of chapters with cliffhangers at the end of every one. Works tailored to the science of children's book writing, as best as it was understood at the time.

In reading Rehak's history (which I really can't recommend highly enough), it becomes clear that there are specific approaches that were established by Edward Stratemeyer that in fact did push away from product. The biggest of them is the clear sense that he cared about his readers. He answered their letters by hand — letters coming in from all over the country, everywhere the underground trade in syndicate books took place across backyard fences and in empty stickball lots.

If anything, the decline of Nancy Drew over the years can be traced back to one thing above all: the sense that those who handled her, over time, came to care more about what Nancy Drew could do for them, as a business, than they did about what Nancy Drew could do for their readers. Harriet Adams came to see Carolyn Keene as a personal alter-ego, and it hurt the books. The last time the Drew franchise was "reimagined" for print the current owners of the property had her as a boy-crazy shopaholic teen. That version is off the market now, whereas you can still buy reprint editions of the original texts from the 1930s, cloche hats and roadsters and all.

Where does this tie back to games as art versus games as product? It's simple, really.

When you create something thinking first of how it will benefit you, you are making the kind of product that people call "soulless" or "unethical."

When you create something thinking first about the value it will provide the customer, you are doing the thing that builds lasting loyalty.

Make no mistake, providing value to the customer is the heart of a lasting business. It's one of the things that metrics measure poorly. And it is the direction in which art lies.

The simplest measure I can think of is to ask yourself whether your product is building a community. If it is, you have managed to tap into an emotional relationship. Measure away, and be as empirical as you have the will to be. But do not forget, ever, to nurture that little flame of real connection — the fan letters, the dogeared books, the fan conventions, the many things that show that really, you don't own this particular piece of the landscape.

Oh, you may own the franchise rights. But Nancy Drew really belongs to those that read her, and you cross those passionate people at your peril. In the long run, the stewardship of something like this offers far far more monetary value than creating anything disposable. It is where product meets art.

Don't do things for your sake. And don't do them for the sake of Nancy Drew, either. Do them for the sake of the little girls who grew up to be strong women, and the lasting impact and connection you will have to those customers, people, fellow journeyers, and friends.

January 9, 2012

Improving F2P

Are you one of those game developers who think that free-to-play games suck? You think they're soulless, or that their builders do not understand how to treat a customer? Or why games are sacred and special?

After all, f2P developers are often looked down upon by traditional game developers, particularly indie ones, as not being artistic.

Well, in the spirit of greater understanding on all fronts, I'm here to tell you how to understand these developers.

The thing to understand about the free-to-play market, and its best developers, is that F2P developers treat everything as science. Everything is subject to analysis, and everything is subject to proof, and the business process is about seeking what works. If what works happens to also be an original, innovative, interesting design that meets a checklist set of criteria for being art, well, all the better. But really, it's about what works.

We have to be honest with ourselves. There is an awful lot of stuff that we have cherished for a long time in the games business which turns out not to work. Sometimes it takes us years to shed the scales from our eyes about the fact that hoary conventions of yore are just that — conventions, mutable and open to change.

A screenshot from the Atari version of Panzer-Jagd.

After all, was not the great innovation of World of Warcraft that it "removed the tedious bits"? Many of those tedious bits were "proven mechanisms." And regardless of whether we feel that some babies went out with the bathwater, there's a certain part of you that has to go with what worked — and if a few babies going out with the scummy water is the price, then, well, it can be hard to argue against.

There is also the plain fact that it takes a player to play a game. What worked for grognards who were willing to fix the BASIC errors in Panzer-Jagd on the Atari 8-bit (*sheepishly raises hand*) does not necessarily work for the player who delighted in Doom, which in turn fails the player tossing angry red birds at hapless pigs.

The field moves on because the audience does, and what works moves with it. Having some science in the mix to track, assess, and predict those movements is only common sense.

And the more the audience divorces itself from we who make their entertainment, the more important it is that we be clear-eyed about what their tastes and behaviors actually are. And that, in turn, greatly undermines the value of "experts," — because we are in many ways, the most likely to be hidebound and unable to see past the blinkered assumptions precisely because we built them up with hard-won experience.

But! And it's a big but.

Sometimes, though, what works only works within the field of measurement. If it turns out one of those useless mewling babies was going to grow up to be Einstein, we would have been pretty dumb to toss him out when he was a sullen teenager (even if he did get good grades). A lot of things fall outside of the typical field of measurement.

Anything that unfolds over a very long period of time. By the time you have true long-term data on a split-test, you've essentially chosen a path through inaction.

Anything that lies in the realm of emotion is invisible — we can easily see results, but we cannot see, barring a focus group, the whys for a given action. (There are various measurement techniques, such as net promoter score, which try to get at this indirectly).

Anything that is a short-term loss for a long-term gain. Many sorts of behaviors players might engage in may pay out when considered as a systemic aggregate, even though regarding them as a funnel may show them to be terrible. One example might be character customization — it's an extra step that likely costs some users in an F2P funnel, but it may also yield far greater revenue over time due to character customization.

Anything that exists outside of the game proper, where it can be hard to tie cause and effect together. Examples include things like community development, the value of strategy websites built by players, etc.

Most critically, measurements are excellent at telling you where to iterate. They are not so good at quantum leaps.

The place where expert opinion still has great value in the F2P world lies in getting out of the hill climbing that pure metrics optimization puts you in. Metrics help you find local maxima, not the highest point in the possibility space. Making good decisions about what sorts of new features to test, for example, is something that goes better with expert opinions in the mix. There are other areas where it matters as well — a highly visible one today being marketing.

It has been highly interesting to watch the rise of marketing programs in social games. Social game companies (not so much the Asian companies or those with MMO in their DNA) have had their own blind spots in thinking about retention in general, so a lot of the hill-climbing has aimed towards maximizing short-term revenue. This can be easily seen in the near complete lack of brand-building in the social games space. But maximizing short-term revenue, while a perfectly valid business strategy, starts to break down as the cost of developing and deploying a game rises. Gradually, the space finds itself in need of long-term revenue models to offset the rising costs.

As budgets and launch polish bars have risen, classical game development knowledge is moving more to the forefront, at least at larger social game companies, because suddenly the "fail fast" model has a much larger upfront investment than it used to. "Fail fast" and "launch early and often" work best when product is cheap to deploy. The ability to envision a viable larger product is a skill set that mostly comes from experience. And at this point, the social game space has raised its own homegrown experts in that, as well as bringing in many from traditional videogames.

Those game developers who look upon free-to-play and lament the lack of retention, community, branding, narrative, or whatever, would best serve the games and the customers by embracing the science. Doing so does not mean denying their instincts, though they may well learn a bunch along the way, and have some beloved applecarts upset by hard data.

If you ask me, the best way to make F2P games better would to find ways to provide provable metrics on why the things we value add to the bottom line. Community, artistry, narrative, brand, retention, customer sentiment, whatever your particular religion is — find a way to measure cause and effect and demonstrate the business value. For example, provide specific data on how forum dwellers measurably increase your bottom line, and any F2P company will immediately start optimizing for it.

And by the way,this should matter to you even if you aren't doing F2P right now. After all, if you are not yet working at a free-to-play company, you probably will be soon, precisely because science is better than religion at actually solving problems.

If something is neglected in the F2P world, it is probably because it isn't easily measurable. Not because the companies hate the traditions of games, but because they are empiricists above and beyond all else.

January 8, 2012

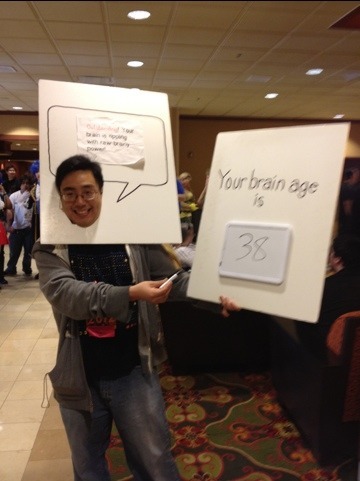

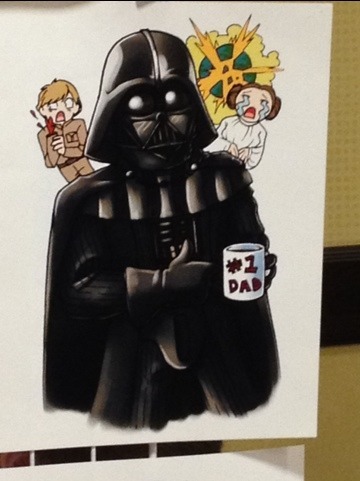

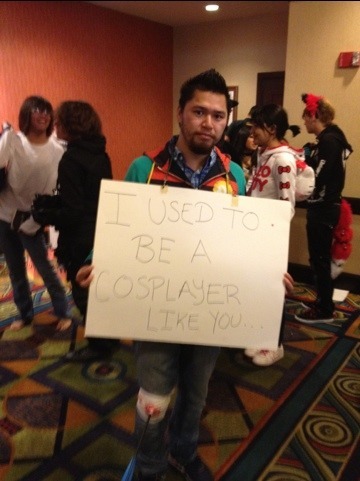

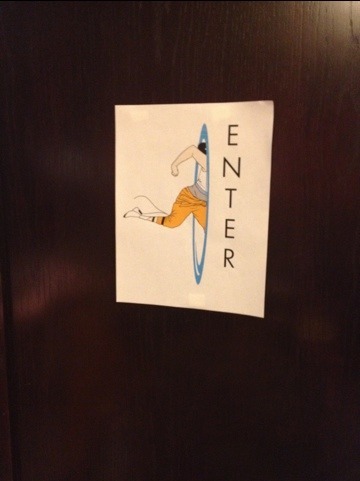

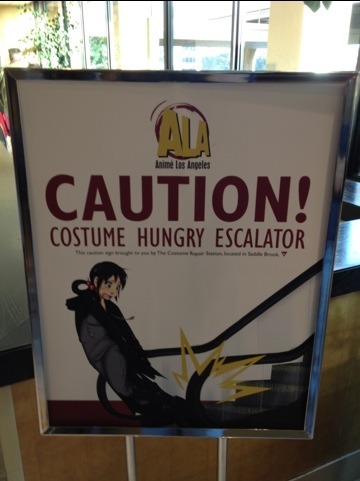

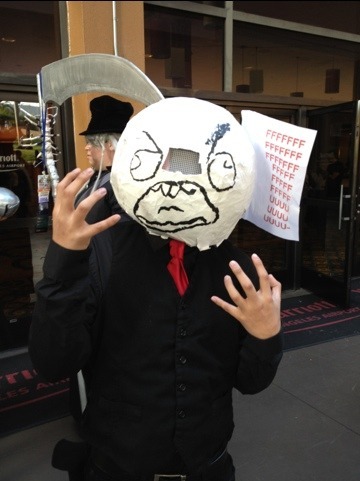

Pics from Anime LA

Here is an assortment of pictures from yesterday at Anime LA. I spent the day there shepherding a gaggle of teen girls who were all doing Homestuck cosplay.

If you watch my Twitter feed, you have already seen these. The one of Darth Vader as #1 dad went a tiny bit viral. There are also a TARDIS, a bunch of candids as people try to eat hamburgers while in costume, a

walking rage comic that was my favorite costume of the show, and of course, there is an arrow to the knee.

January 7, 2012

Some times you should write new code

A fair amount of folks have taken the last few posts (on making games more cheaply and on rigid programming philosophies) to a bit of an extreme further than I intended. So in the spirit of contradicting myself, here are some good reasons to write new code.

When you have something new to learn.

I still remember how proud I was when I independently invented the bubble sort in response to a problem. Then how baffled I was when I tried to figure out how quicksort works.

Writing your own version of a known solution is a fantastic learning tool. Trying to learn how to write jazz progressions? Grab a jazz song, change the key, and start modestly tweaking the chords (an 11th into an augmented, or whatever). Then build your own melody on top of it. Trying to learn how to draw? Start copying people who know how. Trying to figure out how a given game genre works? Try cloning or reverse-engineering a game in that genre. It's a classic method of learning and there is no shame in it. If you have any creative spark, you'll quickly move past this sort of journeyman work and start adding your own elements to it. (This is one of my caveats to Dan Cook's post on game cloning).

I really enjoyed the process of learning every aspect of client-writing when working on Metaplace (I wrote a client — the first one, actually! — and maintained it for a year or so before we switched to the "real" clients). I did things I had never done before. It was a great learning experience. I may never do those things again, but that's fine.

When you want to invent.

A lot of the things I want to do involve having stuff baked into the engine at a deep level. And that means that retrofitting them into an engine can be hard. If you are really working on something new, then sure, you are going to have to write code.

It can be hard to tell when the things you are trying to work towards is a superficial bell-and-whistle or is really integral to the product. In the case of the procedural terrain in Star Wars Galaxies, there was a fair amount of inventing there. But there was also a lot of research into past work on terrain generation, Perlin noise applications, and so on. In the end, it touched many elements of the game: it allowed very large planets without comparably huge data files; it drastically cut the development time for the title; it allowed the terrain to be dynamically modified algorithmically, which enabled free-form structure placement for houses and mob spawns;it even allowed a neat way of adjusting graphics detail level to accommodate a wider range of target client machines.

Now, there were plenty of problems that it caused too! But my point is that there simply wasn't a solution available that happened to do all that, so inventing what ended up being a large and complex system was the choice.

When the available solutions are too big.

Sometimes, there's stuff like a giant physics system or a huge STL library or whatever that you could just use. But it is a Swiss army knife that bloats your codebase, makes your executable too large to fit on a mobile device, or adds in extra complications you just don't need. It's one thing if your game needs gravity; it's another if having gravity means that every rock in the world is going to collide against the ground every frame, which may result in your whole game running too slow.

When you see the real problem.

Sometimes you have a customer, and sometimes the customer is yourself. Either way, the following applies: you need to find out what the customer actually needs, rather than what they are asking for. They (yourself included!) usually don't know. They will ask for something that is too big or too small.

Finding the sweet spot there takes practice. I look for the elegant solution that can grow with the customer to some degree, but also outright blocks them from getting into trouble. (I am just as prone to get myself into trouble as any customer would be). Customers, yourself included, often ask for a solution to a use-case by describing the solution they want, rather than the use-case.

I don't have any very specific advice to give on this other than

Try to think about the problem abstractly. They might be asking to cache an image, but really, if they need to cache an image, they probably need to cache several different kinds of things. They might ask for a tool that lets them specify points on a curve for AI motion, but really, they're asking for better ways to control AIs, and think that the path tool is the best solution. They don't know what you can actually provide, so they ask for something they already know about that meets immediate needs, and stop there.

Minimize. By this I mean, pursue something elegant. Few moving parts will often give more expressive capability than a complex system. I started thinking this way when I became fascinated with the principles behind artificial life. If you go back and read the Ultima Online articles on the AI systems there (1, 2, 3), you'll notice that the system is deliberately limited to very few variables. In fact, I recall going to Scott Phillips and asking if it was OK to burn one more byte on a variable for aversions… A great example can also be found in this phenomenal article on the AI in the original Pac-Man. Notice how four ghosts have radically different behaviors, they interlock, and yet they can all be described with remarkably little code. (Going back to classic arcade games is always a great lesson in systemic design).

The bottom line though, is that the sweet spot is going to pleasantly surprise the user, whether that is you yourself or someone else, precisely because it solves the real problem that the user imperfectly understood.

When it's the puzzle for the player to solve.

Games are usually for fun. Fun is about learning. Learning requires there being new puzzles to solve. New puzzles do not come out of a code library.

A perfect example would be when you go to create the AI for your opponents, whatever the game may be. There are AI libraries out there, certainly. But an AI library would not have given that Pac-Man code. Saying "embrace code reuse" doesn't mean "never write code." And especially for something like AI, where it effectively is the black box aspect of the game that the player is trying to figure out (and therefore from which they derive their learning and hence fun).

So, why would you want to not write new code for AI, particularly if a) you haven't done it before b) you want it to do something that you can't find an off-the-shelf solution for c) you have some inventing to do? It's going to be where your game lives or dies, and if you reuse someone else's wholesale, they will have played your game before, and you are no longer making a system-driven game but a content-driven one.

That said… you'll probably need A*, and attempting to reinvent it from scratch is an unnecessary delay.

January 6, 2012

More on making games cheaply

I only offered 6 points, but 3 of them are ones that people are wanting to argue about!  I suppose that is a pretty good hit rate…

I suppose that is a pretty good hit rate…

A few folks took exception to my comment that "code doesn't rot, our ability to read it does."

The first objection is that most code is born rotten, that it is rare to find code written to the standards that allow it to be easily maintained. I can't really argue with that, though of course there are plenty of practices that ameliorate this: code reviews, code standards, etc. I'd answer with "that's just code where our ability to read it perished as it was being typed."

The second objection is basically that platforms shift out from under code. This is absolutely true — but is also a sign that you're not actively maintaining your codebase. Times of truly catastrophic platform shifts where everything you did is invalidated should be relatively rare these days, honestly.

That said, if the platform really does shift out from under you, I think it's a great opportunity to ask yourself whether it's time to port or rewrite. If the new platform offers new capabilities, then you should seriously consider rewriting and refactoring your architecture as you go.

My intent here was not to argue "never write new code" nor "never rewrite code." For example, stringing together libraries is usually a bad idea. Then again, it sure does seem like most libraries turn into sander/screwdrivers over time!

Really, this was about fighting back the NIH syndrome, and the impulse to rewrite everything all the time. Heck — I myself actually prefer to have control over the tech base and the game design, because to me they are so intertwined… and virtually no engines do the specific things that I am asking for (say, procedural planet generation, for example). But then, I still look for a renderer that works "out of the box." Keep the risks to the new stuff without which the product cannot exist, basically.

Ted Brown left a comment over on the BoingBoing article about the blog post, taking issue with two points I made:

…big design docs do have a time and place. At the beginning of a project, it forces the team to eliminate as many assumptions as possible. And when the team gets large or geographically distributed, concise and updated documentation is critical for production to run smoothly. Obsolete docs that are not actively pruned are landmines, yes, but it's a chore, and creative designers hate chores. So they badmouth it instead of finding a better solution, like making it a job task for someone.

Building a big design doc at the start of the project is the worst time possible, IMHO. Paper docs do not contribute very well to eliminating assumptions — instead, they tend to compound them, because you are layering assumption on assumption. In Ted's next point (quoted below), he makes the point that you can't test interactivity, analog elements, and timing with paper prototypes. Well, you can't test anything with a paper design doc. You can only describe. There's value in the exhaustive working through of possibilities are careful thinking about contingencies, and it's a valuable discipline to learn — but the problem with engaging in a long chain of logic on paper is that if any given step is wrong, you invalidate an awful lot of work.

I find it better to test at each assumption, which requires moving to working prototype as fast as possible. Documenting after that is fine with me…! But again, I prefer concise, bullet-pointed docs at that point, not paragraphs. One of my most painful professional memories is the amount of effort we put into making massive design bibles for first Privateer Online (which never saw the light of day) and then Star Wars Galaxies… they were gorgeous documents with piles of detail, and their ultimate relevance to the eventual product was fragmentary at best.

I fully agree that concise design docs are extraordinarily valuable as production proceeds. But they're better when they document the prototypes, and are more like functional specs for implementation. I am actually all too prone to spend lots of time on documents myself, so I am not one that regards it as a chore.  Instead, I have to fight this tendency.

Instead, I have to fight this tendency.

I commend to you all this excellent talk on visual design docs by Stone Librande: http://www.stonetronix.com/gdc-2010/OnePageDesigns.ppt . The video is also available on the GDC Vault under GDC 2010 — it's members-only, though. I personally spend most of my design time these days in doing diagrams, checklists, and storyboards.

Two, binary mapping of game states — which is all you get when using dice and cutouts — is great for RPGs and strategy games, but wholly unsuitable for games involving analog states, such as timing (e.g. fighting games) or physics (e.g. anything with a bouncing object). If you are making a game that can be completely described with dice and paper, you are not taking full advantage of the interactive medium. System design is important, but interactivity is what makes a game a video game.

Paper prototype systems all you want. But use code, animation, and art to prototype anything else.

I wasn't saying only use paper and dice. I was emphasizing that prototypes can be very cheap. That said, I happen to know that lots of modern FPSes, to take on example, were in fact prototyped on paper — the mechanics being less important these days than the level design, given where FPSes are in their genre lifecycle.

I would argue with the implicit definition of interactivity as implying near-real-time feedback, and that being the defining quality of a video game as opposed to other sorts of games. But that's a whole other post…

January 5, 2012

My biggest coding takeaway

Rigid programming philosophies are the devil.

Look, I am upfront about the fact that I am not an amazing programmer. I am not even a really competent one. I hack. I didn't go through a CS degree, I don't actually know a lot of the lingo, etc.

On the other hand, I have in fact been credited as a programmer on published games. I have programmed in quite a lot of languages, I prototype my own stuff regularly, and my name is on several technical patents. I seem to have a knack for seeing architectural solutions to problems, and for inventing technical solutions. (I generally prefer to partner with a genius coder for the actual implementation thereof — and have been lucky enough to work with many of them!).

So take everything I am about to say with the appropriate grain of salt.

I have seen too many projects get hosed by "the right way to do things"… like say planning your entire game in UML on three hallways worth of paper on the walls, only to find the resulting code too slow to actually use (this is a true story… and I apologize to the many friends and extremely smart folks who worked on the project I am talking about!). Or insisting on the absolute perfect approach to object-oriented or domain-driven design or whatever, when two lines would get you the same result with better performance, less obfuscation, and easier maintainability.

The right way to do things the first time is the way that gets it working the fastest so you can see if your solution even makes sense.

The right way to rewrite it once that works is to make it fault-tolerant and scalable.

The wrong thing to do is build a giant system first, and try to account for every possibility. Odds are very good that you need to write a screwdriver, not a power drill that can double as a belt sander. And really, in the long run, wouldn't you rather have a tool chest with a solid screwdriver, a decent hammer, and a good pair of pliers — rather than a power drill/sander/screwdriver than can pound nails with its handle?

This doesn't mean that you don't plan ahead. Sure — your first pass should include as elegant a solution as you can think of for the actual problem at hand; it just shouldn't include solutions for problems you invented for yourself. And it doesn't mean that you might not end up with complex systems in the end. Sure — over time, you will encounter new problems, and it will turn out the hammer you already have can handle them with minor modifications — which can turn into cruft over time if you are not careful.

But why start further down that path than you need to? A is a cool idea and a useful pattern, not a solution to every problem.

FWIW, I feel the same way about religious adherence to project-management-philosophy-of-the-day stuff too. Basically, as soon as I hear "we're doing this this way" followed by a few buzzwords, I can't help but heave a giant mental sigh. So hmm, perhaps the right title for this post should have been "dogma is evil."

Lastly, never trust a programmer who says that he only knows one language. The more in love with one language someone is, the more likely they seem to be to fall into the above trap… and if you are one of said programmers — try more languages.  Each language I have learned has introduced me to a new programming concept that rewrote my mental model of programming in general. It's OK to have favorites — I do! — but it's always best to use the right tool for the job.

Each language I have learned has introduced me to a new programming concept that rewrote my mental model of programming in general. It's OK to have favorites — I do! — but it's always best to use the right tool for the job.

(FWIW, my favorite at any given moment is entirely based on "what lets me stage up a working prototype as fast as possible").

January 4, 2012

Making games more cheaply

There are basically two big things that drive a lack of innovation in games.

The first of them is risk minimization. The second of them is risk minimization.

The reason I say "two" is because some forms of mitigating risk are undertaken with intentionality: purposely making a game that is a clone, for example. This isn't always a bad thing — sure, sometimes it is done in order to capitalize on a market trend, but other times it's done to learn how a given genre works, and in that scenario it's a common and vital tool in a designer's toolbox.

But this post is about the second sort of risk mitigation, which primarily centers around the fact that as games get more ornate, they get more expensive to make. High upfront costs push you naturally and inevitably towards incremental changes, with the biggest risks being taken on content rather than game systems. This is a pattern that leads inevitably towards "genre kings" — and the stage after genre kings tends to be stagnation and loss of audience reach.

So how can we as an industry keep costs down? Well, here's my take, somewhat more elaborated from my now long-ago presentation on "Moore's Wall."

1. Stop rewriting code. Engine reuse, library reuse, etc.

There must be a 95% overlap in what the code does between all FPSes, but somehow FPS developers have giant programming teams.

There is this myth that "code rots." But code does not rot. What rots is our ability to read it. If code worked in the past, it is going to keep working unless something in the input changes. The real reasons that code breaks over time are because we a) fail to update it b) update it too much and let it get crufty and byzantine. It is rare that this cannot be fixed with a refactor.

It's been said by Steve McConnell (in Code Complete) that an average programmer is going to generate 15-50 bugs per 1000 lines of code. Regardless of whether you agree with the notion of measuring "bugs per KLOC", the fact remains: in well-maintained code that has seen constant use, this figure should decrease over time. In a from-scratch rewrite, it is virtually certain to reset the bug count.

The standard argument against all this is "my game is special" or "we need all these new features." Well, tight scope is an enhancement to creativity.  Figure out a way to work with what you have, and you will probably get more creative output than you would have gotten with all the feature adds.

Figure out a way to work with what you have, and you will probably get more creative output than you would have gotten with all the feature adds.

2. Stop chasing bleeding edge graphics. Chase unique aesthetics instead.

There are many reasons why chasing bleeding edge graphics is an issue in holding costs down.

It almost always increases the amount of steps in the artist tool chain, and frequently also increases the amount of training and expertise the artist needs to have (thereby increasing the amount you have to pay them).

It is almost always experimental to some degree when pursued as a competitive advantage, because cutting edge graphics is active research. If you have to triage and select one area to invest in for risk mitigation, it should be in your game system design.

If you acquire the system instead, then you're almost certainly driving costs there too, by requiring a bleeding edge engine version that probably costs full price from your engine vendor.

It almost certainly doesn't help you in brand differentiation, so you ironically end up spending more on marketing, not less thanks to your unique instantly identifiable look.

Bottom line: great art direction beats great graphics technology any day, and it's cheaper.

3. Embrace tools.

It's astonishing how many game teams shortchange tools — even in larger companies where the economies of scale make this a no-brainer. Granted, good tools designers are hard to come by.

If I had to get across one fundamental lesson on tools design, it would be "stop making tools for pros." Pros shoot themselves in the foot more than inexpert users do. They have a propensity to push at the boundaries of what is possible and discover edge cases, or to bring their own backgrounds and agendas to the problem ("this library should work according to this particular programming philosophy" or "the editor has to look just like Unreal" or whatever).

In any project, 90% of the work is in the basics. Invest in that. Make awesome tools, with friendly frontends, for the basics. Data entry, map making, lighting, importing assets, setting up animations. This is stuff you want to be able to hand off to a junior person if need be, because of the sheer volume of it. You are virtually guaranteed that at some point, a non-expert is going to be maintaining or editing this stuff.

Don't build in the ultimate awesome advanced tools into there. They get used a tiny fraction of the time, and you only want the experts messing with that stuff anyway. Leave the 10% on command lines, or let the experts use their custom made SQL-backed Excel spreadsheet for game balancing, or whatever.

Tool complexity — and therefore tool power — is actually a barrier and cost increaser.

4. Embrace procedural content, of all sorts, just don't count on it being the answer to everything.

Procedural content is generally bland & repetitive, and players see through it given time.

It's also something computers are very very good at.

It may be hard to believe today, but ragdoll animations were once in the province of "procedural content." There's hardly an artist or games programmer alive who doesn't apply procedurally generated noise to stuff. Particle systems usually have a random number generator in them. I could go on and on. Get creative with where you can make use of procedurally generated stuff.

You can't make your whole game with it. But handcrafting every detail is a great way to never finish.

5. Embrace systemic game design rather than content-driven design. It is harder to do but makes for games that have longer life with less content.

Particularly in the AAA games market these days, it can be hard to remember what system-driven game design looks like, because we encounter it so rarely. Puzzle games are probably the last major bastion of this design approach to have serious visibility to gamers.

But the fact is that a systemic game design is far more likely to be played decades from now than any content driven game design. For one, it probably embraces procedurality. For another, it probably eschews the graphics arms race. For a third, it tends to have less special case code than a content driven game and is therefore easier to write, easier to maintain, and easier to reinvent and extend.

Every major game genre is born from an initially systemic approach, even the most content-heavy ones like adventure games.

Don't get me wrong, systemic game design is hard. Harder than replicably pouring content into a fixed mold, because it entails your creating the mold as well. But the key here is that in an competitive market, a fresh systemic design will require less content investment than using someone else's systems and putting your own content in — because then you have to provide n+1 volume and polish of content than the title you cloned/reimagined.

And if you hit the jackpot of systemic game design — a game that has enough emergent properties and strategies to keep generating fresh scenarios from the system — then you will have actually created more content hours than a static approach.

The key in systemic approach is, as I have said before, in attempting to create NP-hard problems.

Side note: some may object to this emphasis on the grounds that the prevailing free-to-play business models are premised on selling small quantities of content. Well, guess what — the best and most lucrative F2P games are built on solid systemic foundations, not on static content. Think collectible card games, for example. In addition, the best virtual goods are consumables, which again points back at a systemic core game, rather than a content-driven one.

6. Embrace prototyping. Make your game playable and fun before you have any art. Stop writing big design docs.

Big design docs are useless. There, I said it. Trying to build a game off of one is like trying to recreate a movie from the director's commentary track. They are largely castles in the air. The only time that big design docs serve a real purpose is when they are describing static content.

Embracing prototyping is a huge mental barrier for people. But it is what gets you to that long-lived self-refreshing systemic game design. You can prototype almost any game with some dice and some index cards. And plenty of ideas that sound good on paper turn out to suck when tried out for real.

Prototypes properly done are cheap. Prototyping is whistling five melodies and seeing which one you remember the next day.

Anyway, that's my recipe.

December 16, 2011

Good design, Bad design, Great design

Good design is familiar.

Bad design is boring.

Great design is exciting.

Good design embraces human nature.

Bad design exploits human nature.

Great design is humane and humanistic.

Good design guides.

Bad design controls.

Great design invites.

Good design drives habit.

Bad design drives frustration.

Great design drives passion.

Good design teaches.

Bad design lectures.

Great design has you teach yourself.

Good design is invisible.

Bad design calls attention to itself.

Great design calls attention to what you can do.

Good design celebrates accomplishments.

Bad design loudly celebrates minor accomplishments.

Great design enables accomplishments.

Good design does what the user wanted.

Bad design does what the designer wanted.

Great design does what the user didn't know they needed.

Good design is at the user's skill level.

Bad design never asked the user.

Great design makes everyone think they can use it.

Good design is intentional.

Bad design is planned (exhaustively, on paper).

Great design reveals itself while working in the materials.

Good design gets people to pay for utility.

Bad design gets people to pay as quickly as possible.

Great design makes money as an incidental consequence.

Good design makes companies.

Bad design can make plenty of money.

Great design builds legacies, cultures, and communities.

Good design converses.

Bad design tells.

Great design connects people.

Good design executes on the possible.

Bad design ships on time.

Great design reaches for the implausible.

Good design has only the parts it needs.

Bad design is cluttered.

Great design has fewer parts than seem possible.

Good design doesn't fail.

Bad design fails a lot.

Great design fails even more.

I have done good design.

I have done plenty of bad design.

I always want to do great design.

December 13, 2011

Rules versus mechanics

Ian Schreiber posted on Twitter asking

Game designers: in your everyday use of the terms, is there a difference between "rules" and "mechanics"? If so, what?

I do make the distinction, and I had to think a bit about how to even phrase it. So here's a quick thousand+ words on it.

First off, I think these are both terms that will feel different to a player vs a designer.

Let's consider a simple example: jumping in a platformer.

Let's consider a simple example: jumping in a platformer.

In a platformer, the player sees the instructions "you can jump by pressing this button." They see the rule that if they miss a jump, they fall and die. They also see that if they land on an enemy, it kills the enemy, which is another rule. They then think of all of this as the jumping mechanic.

From a more formal point of view, we can use Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman's terms and break apart the instructions and rules into the three types of rules that they describe in Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals.

Constituative rules are the ones that are mathematical. Fall and die. Make contact with an enemy whilst at a higher screen-space position, enemy dies.

Operational rules are what is printed in the instructions.

Implicit rules are unstated rules of behavior (no smashing the console when you die).

Now, the idea that you can jump and land on an enemy is not in here as a rule. That's because it isn't one. It's emergent out of the system of rules.

The classic MDA paper by Hunicke, Zubek, and LeBlanc makes the analogy this way:

The MDA framework formalizes the consumption of games by breaking them into their distinct components:

Rules -> System -> Fun

…and establishing their design counterparts:

Mechanics -> Dynamics -> Aesthetics

Under this model, jumping to land on an enemy is clearly in the realm of Dynamics, which

…describes the run-time behavior of the mechanics acting on player inputs and each others' outputs over time.

The trick then is reconciling all of the Salen/Zimmerman rules types with this model. And indeed, when we look at examples of mechanics in the MDA paper, we find that the definition there tends to be centered around systems — MDA is essentially a system-based way of looking at things.

In an atomic model of game design, such as those used by all the game grammarians (myself, Dan Cook, Stephane Bura, etc), the core precept is that games are made out of games, which I call ludemes after Ben Cousins (Dan calls them "skill atoms"). Each ludeme has rules in its own right; each ludeme may exhibit mechancs, dynamics, and aesthetics. And most importantly, game atoms nest. They're recursive. Essentially, each ludeme is a system, a little machine, and when you dig into what is inside the machine, you find smaller machines, eventually reaching the game equivalent of the wheel, the lever, the fulcrum, the pulley, etc.

Many of these ludemes will never have all three types of rules that Salen and Zimmerman describe. Game grammar focuses solely on the constituative rules. Its objective (as best described in Dan Cook's article "The Chemistry of Game Design") is to focus on what a given ludeme is teaching the player. Common higher-order ludemes (and therefore, clusters of ludemes) are then a direct match-up to Björk & Holopainen's game design patterns.

Many of these ludemes will never have all three types of rules that Salen and Zimmerman describe. Game grammar focuses solely on the constituative rules. Its objective (as best described in Dan Cook's article "The Chemistry of Game Design") is to focus on what a given ludeme is teaching the player. Common higher-order ludemes (and therefore, clusters of ludemes) are then a direct match-up to Björk & Holopainen's game design patterns.

Critical to this is the notion of separating the feedback from the "black box" machine that lies at the heart of the ludeme. Under this sort of model, "falling and dying" is properly understood as being feedback given by the system on the way to a goal — reaching the next platform. So it isn't a rule at all — it's an outcome, which is not the same thing.

So, if you ask a player, they may tell you that falling and dying is a rule, and that jumping is a mechanic, and that landing on an enemy is also a mechanic.

If you ask a designer (well, a quasi-academic one like me), you might get a lot of different answers based on what of the above they use as their preferred tools for understanding how games work.

So: after all that, my answer to whether rules and mechanics are the same thing, and if not, how they are different! My approach will be biased by the game grammar way of looking at things.

I tend to think of rules as component elements of mechanics.

I tend to think of mechanics as the "black box" portion of ludemes or skill atoms.

So to decompose the jumping example:

There is a prep stage (existing vectors of motion, specific position of the player's token). These arise out of previous interactions with ludemes in the game. (All ludemes always have a prep stage, which is implicitly defined as "everything you have done previously).

There is an input (pressing the button to jump). The key cognitive challenge is choosing the right prior prep, which given that this is a highly granular movement activity, largely means a timing problem of when to press the jump button.

There is a goal, which is largely determined by player agency. It may be "lan at targeted point," it may be "land on an enemy."

The input enters a black box system, where the input is evaluated.

In this case, the input is evaluated against specific constraints (physics such as vector upwards, effect of gravity, destination location). I call these rules — specifically, of the constituative sort. They are discrete; you can take out gravity, or add inertia on the landing, etc.

The state is updated with the result. In the case of "land at targeted point" you are basically going to make it or not. Feedback is given to the player of either falling and dying, or getting there.

In the case of landing on an enemy, you actually intersect with a separate ludeme altogether, which has as its goal "destroy enemy" and has as one of its rules "collide while in a higher screen space position on the Y axis." Feedback is given based on that rule being met.

In aggregate, "jumping" is then a mechanic, because it is inclusive of prep and feedback. "Jump on enemy" is a mechanic too, which includes the entirety of jumping (nested ludemes).

Dynamics therefore exist, as in the MDA model, in the interstices between the mechanic and the player's aesthetics experience — which game grammar would specifically define as the feedback, the elaboration of the mental model of the contents of the black box, and the emotions that our cognitive system triggers as part of its own feedback mechanisms.

So no, to me rules and mechanics are not exactly the same, Ian. But I couldn't think of how to fit the above into a Tweet.