Commodifying culture

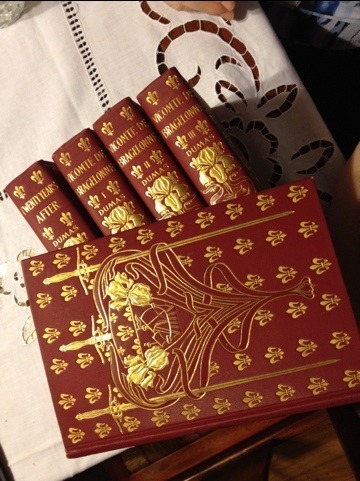

Feast your eyes on the book porn to the left.

Feast your eyes on the book porn to the left.

Go ahead, click on it and get the larger picture.

Gorgeous, aren't they? They're the complete set of the D'Artagnan Romances by Alexandre Dumas: The Three Musketeers, Twenty Years After, and the three volumes of The Viscomte of Bragelonne,the final volume of which is generally better known as The Man in the Iron Mask.

They were published by Thomas Y. Crowell Co., no longer extant as such, in 1901. Not first editions — that would look like this – but glorious nonetheless. Gilt on the edging, inlaid on the relief covers, onionskin endpapers in front of every engraved illustration…

Nice enough that you can still buy an facsimile of this exact edition, alas without the rich red covers and with something fairly hideous on the cover instead.

They're something to hold, to examine. Maybe not to read. Defintely something to have visible on a shelf where people can ooh and aah. They were given to me by my uncle for Christmas this year.

I have more than a few other books like that. I've got a hardcover American edition of the first Harry Potter, signed by Jo Rowling, made out to my daughter with a personalized message. A bunch of old books, a lot of autographed SF novels written by people I know, some of whom are pretty well known: Brin, Sterling, Doctorow.

I have a lot of the same books as epubs on my iPad. And it's qualitatively different. The e-books are commodities, and if one get deleted, I won't have any regrets. Whereas if my complete run of first printings of the Doonesbury compilations (even including the obscure one for the TV special!) were to get lost or damaged, I'd be quite upset.

There is a fetishistic quality to the physical object, a quality that means that I will probably never have a house without books. In fact, now that we have a larger house with bookshelf space, we have carefully placed 4×4 beams towards the back of every shelf so we can double-stack the books and still see every spine (a trick I recommend! Buys you two additional shelves of books per bookcase).

There is a fetishistic quality to the physical object, a quality that means that I will probably never have a house without books. In fact, now that we have a larger house with bookshelf space, we have carefully placed 4×4 beams towards the back of every shelf so we can double-stack the books and still see every spine (a trick I recommend! Buys you two additional shelves of books per bookcase).

Oh, there's a lot of books that probably I don't need and will never read again. But I carefully gather up and keep in order every Ian Rankin mystery novel, every volume of Transmetropolitan, each of the slender paperbacks of Mafalda in the original Spanish. And I make sure they can be seen.

Signaling theory is a small branch of cognitive science which argues that quite a lot of the things we do are intended as signals to third parties — especially prospective mates — about our status and interests. I think of what we do at our house with books as being basically that: a sign of who we are. We're just not the types of people who will ever live without physical books, because electronic copies aren't visible, and aren't valuable.

There is an implicit valuation of cultural objects based on physicality — indeed, implicit calculation of actual monetary value. Rarity matters — whether it's the fact that one of my two copies of M.U.L.E. is still in its original shrink-wrap (the Commodore 64 one, not the Atari 8-bit one — I played the heck out of that one!) or the fact that my print of the goblin market from Stardust is signed by Charles Vess.

In fact, I am having great trouble keeping myself back from boasting about even more of my geek possessions as I write this. I am engaging in signaling to you about what matters to me.

It's gotten a lot harder to signal music. It's everywhere. The rarity and the scarcity is gone. Some music geeks are working hard to bring it back, by putting out vinyl limited editions, precisely because the physicality of the vinyl format, with its generous cover sizes, the patina of survival, the whiff of authenticity from when music seemed (I do say "seemed") less commercial, all seem like the qualities that bring back that fetishistic element. People don't collect the MP3s of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band for the intact cut-outs in the album sleeve (that my vinyl copy from the 60s has, neener neener).

All culture, though, is becoming commodified. And cheapened — I mean that literally, cheapened on the open market. The benefits are enormous:

Even as pro-level content has gotten dramatically more expensive to produce, we have seen the quality of amateur content explode. Now there are Beatles in living rooms everywhere. Far far more people have turned out to have talent than I think was ever evident in all of history.Creative output can be shared fairly trivially, enabling people who have never before had access to libraries' worth of information to learn about darn near anything. Just tonight by daughter was complaining about her biology teacher, and I said that in this world, there's no excuse… just go find another bio teacher at bioteachershangouthere.com. Which may not exist, but should. The point being that where information was scarce, it is now more like air. Polluted, but everywhere.We live in an age where people are sagely telling us to move into tiny houses and get rid of the accoutrements of consumerism. An implicit message is that we should not be valuing many of the things we value nearly as much as we do. After all, is the value of The Three Musketeers in the binding or the text?

Bizarrely, I think for me, at least right now, it's in the binding. Content is ever more ubiquitous. Containers are what has grown rare and precious.

I think of this now with our increasingly digital medium of games. I have a 60s edition of Risk, alongside a modern one. I have a handmade Nine Men's Morris, a Lord of the Rings chess set. I have a MAME cabinet, and I can play Centipede with a trackball, dammit. And I still keep the cases of Playstation 1 games that I have not bothered to boot up in many years. But in not too distant a future, I'll probably be paying quite a lot extra to have a physical object to fetishize and show off my devotion to my craft and hobby.

Someday, when everyone gets to carry around the complete works of humanity on a cufflink, it's going to be interesting to see how we tell each other who we are.