Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2504

November 9, 2010

What Do People Think A Third Party President Would Do?

Ben McGrath's discussion of the endless discussion of a Michael Bloomberg third party presidential bid is appropriately arch, but still doesn't, I think, quite get at the core madness of this talk:

Speaking at Harvard, the day before the election, Bloomberg said, "I think, actually, a third-party candidate could run the government easier than a partisan political President," and then he went on, as he always does, to deny that he intends to pursue the position. He is, as he is fond of saying, Jewish, unmarried, pro-choice, anti-gun, pro-immigrant, and pro-gay-marriage. Add to that a strong allegiance to Wall Street, a weekend house in Bermuda, and his vehemence, last summer, in defense of the mosque near Ground Zero, and it's hard to see how he plays to the populist moment. A recent Marist poll indicates that only twenty-six per cent of New Yorkers favor the prospect of his running.

Yet the dream persists. "I think it's a strong possibility," Clay Mulford, the chief operating officer of the National Math and Science Initiative, and, as it happens, Perot's son-in-law, said the other day. "The mood of the country is not ideological but more practical. The timing is unusually right." Mulford mentioned that a Google search of his name and Bloomberg's would reveal that the two of them met, a couple of years ago, to discuss ballot logistics. "His people put the story out," Mulford said.

The question that needs to be asked about all these notions is what kind of legislative coalition is President Bloomberg supposed to be governing with? The version of ARRA that passed was the one Senators Collins, Snowe, and Specter were prepared to support. So what difference would it have made had Barack Obama been somewhat less liberal? I bet a third party president would initially impress people with his bold truth-telling and lack of need to cater to old bulls on the Hill. But it would swiftly become apparent that the constitution hasn't been repealed, that the only bills that pass are the ones members of congress will vote for, and that members of congress all belong to parties. The only way you'd be able to get anything done would be to find a way to work within the party system somehow.

The point is that most of the stuff people like to decry about American politics—the venality, the small-minded partisanship, the bickering, the corrupt deals—happens in Congress. Wishing for a different president doesn't address any of it.

Trade and QE2

The cavalcade of international whinging about QE2—the Federal Reserve's effort to lower medium-term interest rates—is really telling and important to understand. The first thing to understand it, I think, is that QE2 is not primarily about international trade. The key thing about the United States and international trade is that the US economy is enormous. If Vermont, which is small, were a country then "international trade" would be really important to Vermont and "trade with the United States" in particular would be hugely important. But Vermont's not a country. And because the US economy is so giant the volume of our trade with foreigners is small compared to what you see in most countries.

QE2 is about raising aggregate demand in the United States of America.

Now it is of course true that QE2 will have impact on other countries, and foreign policymakers should feel free to whine if they feel that America's policy choices are inconveniencing them. But that doesn't mean we should listen to them. In this regard I think it's worth doing more than Kevin Drum does to distinguish Germany and China. The Germans are merely being hypocritical about this (that's politics) but the Chinese are being nonsensical. Their problem with QE2 is that they've decided to subsidize politically powerful Chinese exporters by yoking their currency to ours in a way that leads them to import our monetary policy. Since they did that, they now want us to run a monetary policy that would be appropriate for China rather than a monetary policy that would be appropriate for the United States of America. But since the United States of America and China are very different places, economically speaking, it would be nuts of us to do this. Fortunately, China can unyoke itself from us any time it wants by letting its currency float more. They're acting like this currency tether is something we've been begging them to do when in fact it's something we've been begging them to stop.

This, by the way, is what drove me nuts about the proposals to hit China with tariffs unless they changed course. We don't need to coerce or cajole them into changing course, we just need to steer our own ship correctly and not pay attention when they whine about it. They know what they have to do in response and sooner or later they will.

My Application for Peter Thiel

Via Twitter, I see that one of the questions Peter Thiel asks applicants to his fellowship program (which unlike some of his philanthropic endeavors sounds to me like a totally good idea) is "Tell us one thing about the world that you strongly believe is true, but that most people think is not true."

Since I'm not eligible for a fellowship for people under the age of twenty, I'll offer my honest answer which is that guys like Peter Thiel are much more commonly reckless gamblers who got lucky making bad bets than they are brilliant visionaries who can peer into the future and see the best ideas.

In other words, if a thousand guys walk into a casino and all put $1 million down on different numbers on the roulette wheel, then the guys who win all make a second bet, someone will probably walk out of the casino with a billion dollars and an air of smug self-satisfaction. He'll rapidly be surrounded by flatterers and possibly spend the rest of his life talking about how seasteading is humanity's only hope to achieve real freedom.

Meanwhile, it seems to me that the recognition that successful capitalists mostly succeed thanks to good luck and willingness to run unwise risks is actually integral to the case for capitalism as an economic system. If it were otherwise, then we could just recruit Peter Thiel, Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Pete Peterson, Charles & David Koch, and George Soros to run the Central Planning Committee. After all, those guys are smarter than the rest of us so it makes sense to put them in charge of allocating almost all the capital in the country and not just the puny share they're able to obtain personally. In the real world, that'd be a disaster. There are a bunch of reasons for that, but that fact that a healthy fraction of the super-rich aren't nearly as smart as their flatterers think they are is on the list.

Oldster-Fueled Backlash Against The ACA Unlikely to Reflect Support for Small Government

It's been pretty widely remarked that the surge in Republican voting last week was driven largely by old people, but I'm really shocked by the extent to which the MSM has failed to derive the obvious conclusion from this. After all, criticism of Democrats had two main thrusts. On the one hand, incumbents were castigated for too much spending. On the other hand, incumbents were castigated for cutting Medicare. Surely both critiques were persuasive to some audience. But which critique do we think specifically found traction with senior citizens? Pretty clearly Medicare.

Now politics ain't beanbag, so if Republicans want to slam Democrats for reducing Medicare's projected future outlays they're free to do so. But you can't ride to victory on a backlash against Medicare cuts and then claim to be riding a backlash against big government. Medicare is big government. Really big!

Pat Garofalo pointed out yesterday that Jim DeMint (R-SC) is trying to square this circle by somehow pretending that Paul Ryan's "budget roadmap" doesn't cut retirement programs:

GREGORY: But then, but where, but where do you make the cuts? I mean, if you're protecting everything for those, the most potent political groups like seniors who go out and vote, where are you really going to balance the budget?

DEMINT: Well, look at Paul Ryan's Roadmap to the future. We see a clear path to moving back to a balanced budget over time. Again, the plans are on the table. We don't have to cut benefits for seniors, and we don't need to cut Medicare.

The reality is that Ryan's plan involves completely eliminating Medicare and replacing it with a less-generous system of vouchers that will let you buy private insurance. At root, the agenda here is totally incoherent.

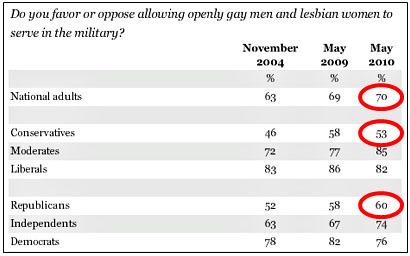

DADT Repeal and the McConnell Way

Looks like Republicans aren't going to back down on their threat to filibuster a defense appropriations bill unless it's stripped of Don't Ask Don't Tell repeal legislation, and it looks like Democrats are going to cave.

Just as a pure political spectacle here, this is a thing to behold. Filibustering defense appropriations bills is politically risky. And to do it in order to support a hugely unpopular position on a related issue is a giant risk. It'd be one thing if 60% of the public was on the Republicans' side about DADT. But it's not. Instead this is a 70-30 issue that cuts against them.

But not only are they getting away with the filibuster, they're turning their obstruction into a political winner by forcing the progressive community into circular firing squad mode. I try really hard to think of politics in terms of the substance of things rather than the quality of the performances, but from a sports fan type perspective you really have to admit that Mitch McConnell has delivered a gutsy virtuoso performance as a legislative leader. It takes a real kind of vision to recognize that relentless obstruction even of overwhelmingly popular progressive ideas can be turned into a political winner by creating fractures in the other side's coalition. Meanwhile though the political reporter set admires nothing so much as a winner, I feel like they still haven't really grasped how the McConnell Way works. But once you "get it" your understanding of the legislative landscape really starts to look different. And unfortunately for the country, I'm not sure they get it in the White House either.

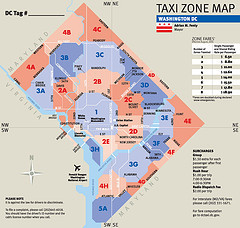

DC Cabbies Don't Like Competition

During his primary campaign against Adrian Fenty, DC mayor-elect Vince Gray was able to attract the support of a very wide array of interest groups without making any formal promises. Now, though, the people in whose debt he is feel that it's time to pay the piper. Cab drivers, for example, were solid Gray backers because they (accurately) blamed Fenty for imposing a rational meter system on the city rather than an insane zone system. Even the cabbies aren't crazy enough to actually suggest going back to the old system, but they do have a different bad idea:

Derje Mamo, a taxi driver who helped run transportation for the mayor-elect's campaign, said cabdrivers already are pushing Gray to reshape the Taxicab Commission and allow for the creation of a medallion system. A medallion or certification system would limit the number of cabs operating in the city. Proponents of such a system argue that too many taxis are flooding D.C. streets. 'He's got one year, that's it,' Mamo said."

Too many taxis? Systems of this sort are widespread in other cities, but they're not a good idea. Basically if you think it's too easy and convenient to hail a cab in Washington, you'll love an artificial regulatory restriction on the supply of taxis. In particular, if you think the city's peripheral neighborhoods are too well-served by cab drivers and that we need to shift to a dynamic where you can only hail a cab in the downtown core, you'll love this plan. You also might like it if you're an incumbent cab driver who wants to restrict new entrants' ability to compete with your business.

If Gray is smart, he'll recognize that this is change we don't need. But I worry that Gray will think the lesson of his victory is that city government should always bow to interest-group pressure.

November 8, 2010

Endgame

I swear I'll do my best to comply:

— Deregulation and suburban lawn care.

— Activist judges impose sharia on Oklahoma just as the voters feared.

— Barbershop crackdown because Florida needs more unemployed people.

— Call it the WTF Were You Thinking Project.

— Karl Smith has made charts and graphs that should finally make it clear: the problem is a lack of aggregate demand.

— PBS on Senate dysfunction.

The Postal Service, "Nothing Better".

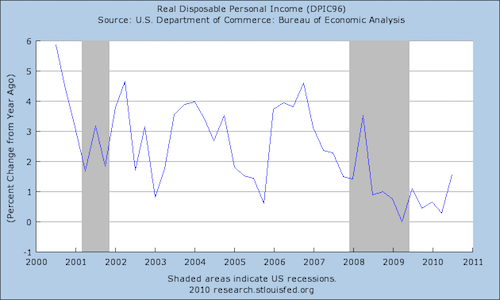

The Number That Matters

The labor market indicator I see discussed most often is the unemployment rate. Sometimes people push into the "broad" unemployment measures. But in political terms, I doubt this is the most important indicator. After all, even at the depth of the Great Depression the unemployed were only a minority of the population. And there's little sign that high-unemployment demographic sub-groups (African-Americans, young people, high-school dropouts) experienced some kind of particularly sharp turn against Barack Obama.

Something better to think about may be the change in real personal disposable income:

Another point where this is relevant is the continued mumblings that there's nothing policymakers can do about unemployment since all this joblessness is "structural." The labor market has been delivering bad outcomes across the board, not just a targeted blow to a handful of suddenly unemployably inept individuals.

The Vision Thing

Ross Douthat explains why he won't be missing Charlie Crist, Evan Bayh, or Arlen Specter and has wide comments on the general situation facing centrist legislators:

We hear a lot about the perils of political polarization, and for understandable reasons: America faces structural challenges that probably can't be addressed by one party alone, and the waning of bipartisanship is one of the many forces that make a Greece or California-like endgame seem depressingly plausible. But if a polarized political system produces fewer centrists overall, it also increases the power and potential leverage of the centrists who remain. For a time, the most important figures in the debate over health care reform were Chuck Grassley and Max Baucus; later on, that role passed to Ben Nelson, Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe, among others. (The same was true in the stimulus debate, the financial reform debate, etc.) A swing vote in the U.S. Senate should be able to wield disproportionate influence over the design of legislation; a swing bloc, if one existed, would essentially have veto power over whatever the majority wanted to do. And so the legislator who wastes this power — by engaging in horse-trading without any larger vision, by griping constantly about their own party's mistakes while voting the party line on every major piece of legislation, or by simply being a self-interested, unprincipled cynic — is as much to blame for the dysfunctions of the American political system as any uncompromising partisan of the left and right.

I think this was an underrated sub-plot of the 111th Congress. The people who occupied the legislative pivot points showed us basically nothing in the way of vision. When Scott Brown held all the leverage on financial regulation legislation, he used it to get a special carve-out aimed to benefit the bottom line of Massachusetts-based banks. Blue Dogs exempted car dealers from otherwise applicable consumer protection rules. Ben Nelson asked for the "cornhusker kickback."

This kind of thing is one reason I'm hoping that instead of obsessing over finding compromises with Republicans the President will refocus his attention away from the legislative arena. Left to their own devices, maybe some of the pivoteers will realize that they have an obligation to actually frame some kind of proposal for coping with the country's problems.

The Unrepresented

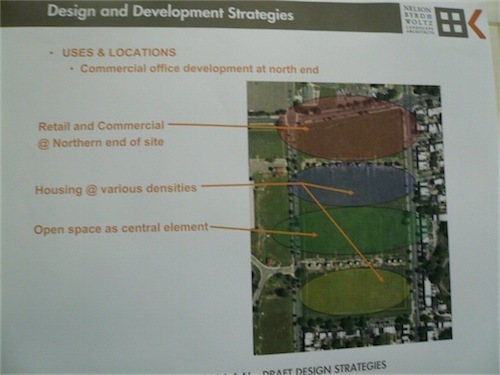

There's a 25 acre chunk of land in DC located just south of a major hospital complex and otherwise surrounded by residential neighborhoods called the McMillan Sand Filtration Site. It's no longer needed for water-filtration purposes, so the idea is to redevelop it as someplace where people can live and work and shop. That requires a regulatory plan in which the interests of people who live in the McMillan-adjacent neighborhoods is being given heavy weight.

Lydia DePillis reports that one thing they want is low-density development, especially on the most promising retail corridor:

Based on the surrounding geography, master planner Matt Bell of EEK and landscape architect Warren Byrd of Nelson Byrd Woltz outlined a rough sketch of how the site's 25 acres might be apportioned: Office buildings would go on the north end, across Michigan Avenue from the medical center; townhouses would go on the south end, along Channing Street; with multifamily residential buildings and park space somewhere in between. They also proposed building higher towards the west side of the site, so as not to crowd the short townhouses on North Capitol Street, though that corridor was identified as the most viable location for retail (a representative from Councilmember Harry Thomas' office relayed North Capitol residents' strong desire not to have tall buildings across the street).

My very strong suspicion is that the North Capitol Street residents have a subjective understanding of their actions as jeopardizing the interests of rich developers. Harry Thomas, likewise, presumably sees himself as standing up for regular people against the rich developers. But what about the future residents of the McMillan site? Who's asking those people whether they'd prefer taller buildings and a richer retail environment? And who's asking the people who won't be able to move to the McMillan site in the future but who would have been able to move had higher-density construction been permitted?

Similarly, how about the ecological impact? It's not as if the people who don't move to McMillan will just vanish. Instead, they'll live someplace else—someplace with longer commutes—and the emissions from their automobiles will in a small way contribute to environmental problems around the world.

Of course this is just one largish patch of land in one American city. But just about every single infill planning process in America suffers from the exact same bias. The views and interests of people who currently live nearby are represented, but the views and interests of the future-people impacted by the process aren't. Consequently, each planning process is systematically biased toward permitting too-little development.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers