Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2507

November 5, 2010

Bilingual Polling

Most discussion of potential sampling error problems with polling that I've heard in recent cycles has focused on cell phone only households. Time and again, however, pollsters seem to be able to adjust for this correctly. Joshua Tucker rounds up some research on a different potential source of error—monolingual polling in a country where many people primarily speak Spanish. This could account for the way polls seem to have systematically overrated Republican performance in Nevada, Colorado, and California.

Time to Scrap the Filibuster

Tim Fernholz that January would be an excellent time for the 53 Senate Democrats and Vice President Joe Biden to come together to eliminate the filibuster and return the senate to a majority rules dynamic.

I entirely agree. There's obviously some sentiment that the wake of an electoral defeat is a bad time to push the envelop on something like this. But I disagree. The fact that John Boehner is going to be Speaker of the House means that nobody is going to feel that the filibuster is the only thing standing between them and Barack Obama's socialist gulag. Instead the practical import of the filibuster is that it will prevent executive branch nominees from being confirmed in a timely manner. That's much lower stakes, and it's an issue where the President will have a clear upper hand vis-à-vis the unpopular Senate Republicans.

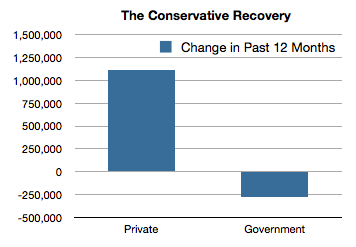

The Conservative Recovery

Here's the shape of the past 12 months' worth of job growth:

In a normal year, government employment goes up. After all, the population is growing so providing the same quantity of public services requires more personnel. At the same time, the workforce is growing so it's possible for the economy to support a larger quantity of public sector workers. And you would assume that during a period of allegedly explosive growth in the size and scope of government, that public sector employment would increase by an unusually large amount. Instead, it fell.

Which is to say that conservatives have been getting the kind of economic recovery they say they want. The private sector is growing and the public sector is shrinking.

I say: the net impact of this has been terrible. They say: what? I don't know. Generally they deny that it's even happening. But is the conservative line that had we laid off more government workers the private sector would have both picked up all that slack and also created even more extra jobs on top of that? My view is that that's backwards. The best time to seek to streamline the public sector is when the private economy is humming along. When the economy is growing strongly, if you lay off a janitor at the DMV he can get a job as a janitor at the new office building across the street. When the economy is growing, if the state lays off an accountant then the manufacturing firm across town might hire a new accountant. But when the economy is weak, you lay off the janitor and it takes him 12 months to find a new job. During that time, all the stores he used to shop at have lost a customer. And all those lost customers are a drag on the entire value chain of manufacturing, shipping, and retailing of goods. That, in turn, makes it harder for laid off workers to find new jobs further delaying the pace of transition.

To me, that's what's happening here. But what do conservatives think? They don't even seem able to acknowledge that government is shrinking.

The Irrelevance of Mitch McConnell

To echo something Josh Marshall said this morning, I think something the press reaction to the election has thus far missed is that Mitch McConnell is now totally irrelevant. Instead, both McConnell and the press seem to be running with the idea that since pre-election McConnell was the most important congressional Republican and post-election congressional Republicans are now more important, that McConnell must now be more important.

But this is wrong. For any bill to pass the House of Representatives, John Boehner needs to agree to it. And for any bill to be signed into law, Barack Obama needs to agree to it. Now you need to ask yourself, who's in a position to blow up a Boehner-Obama deal in the Senate? Not Mitch McConnell, that's for sure. The spoilers in the Senate are going to be rogue ideologues like Tom Coburn, Rand Paul, and Bernie Sanders who might plausibly defect from a bipartisan deal. The players in the Senate, if there are any, will take two forms. One is ideological faction leaders such as Jim DeMint (and . . . I dunno . . . Sheldon Whitehouse?) who could conceivable turn form legislative blocs capable of negotiating. The other is entrepreneurial dealmakers such as Lindsey Graham and Ron Wyden who could conceivably gin up legislative concepts that could become the basis for Boehner/Obama agreement.

But who cares what Mitch McConnell thinks? His main job is going to be coming up with stalling tactics to make confirmation of Assistant Secretaries of Commerce as annoying as possible.

The Limits of Ideological Self-Identification

William Galston has an excellent post about the shifting ideological self-identification of the electorate:

This shift is part of a broader trend: Over the past two decades, moderates have trended down as share of the total electorate while conservatives have gone up. In 1992, moderates were 43 percent of the total; in 2006, 38 percent; today, only 35 percent. For conservatives, the comparable numbers are 36 percent, 37 percent, and 42 percent, respectively. So the 2010 electorate does not represent a disproportional mobilization of conservatives: If the 2010 electorate had perfectly reflected the voting-age population, it would actually have been a bit more conservative and less moderate than was the population that showed up at the polls. Unless the long-term decline of moderates and rise of conservatives is reversed during the next two years, the ideological balance of the electorate in 2012 could look a lot like it did this year.

But of course that leaves us with the question of what implications this carries. To my mind, like most analysis of ideological self-identification it indicates that ideological self-identification is a pretty murky subject. Ask yourself on what subject has the public become more conservative?

Consider gay rights. To shift to the right relative to the 1992 status quo, we would need for every state in which gay marriage is legal to repeal that. We would also need to eliminate civil union laws. And rather than repealing Don't Ask Don't Tell and allowing gay and lesbian servicemembers to serve openly, we'd need to revert to a policy of explicitly authorized inquisitions and purges. Does anyone think that would be popular?

Or health care. To shift to the right relative to the 1992 status quo, we would need (of course) to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Fine. But do you hear Republicans talking about repealing the 2009 SCHIP expansion? I don't. How about the creation in 2003 of a Medicare prescription drug benefit? How about the 1997 creation of SCHIP? Or the Kennedy-Kassebaum Act? Or the Family and Medical Leave Act? I don't hear anyone talking about any of that. Nor do I hear anyone talking about undoing Bush-era increases in federal K-12 spending.

What's happened on these subjects is that the stance one needs to take in order to be a conservative in good standing has become less extreme. In the 1960s, the conventional wisdom was that to be a conservative in good standing you had to regard the Civil Rights Act as an intolerable regulation of private enterprise. Today, only Rand Paul thinks that and he's too embarrassed to admit it squarely.

There are probably issues on which the public has actually become more conservative. There's clearly much more support for the idea that torture is a legitimate tool of governance than there used to be. More interest in immigration restriction, perhaps. Maybe less interest in defense cuts? Obviously I don't think it would have occurred to anyone in 1992 that the government should prohibit the construction of a mosque in lower Manhattan.

The Not-So-Great Game

In case you think it's only the American right-wing whose foreign policy thinking is dominated by paranoid fantasies, Robert Farley offers this account of Russian thinking about Chinese plans to conquer Central Asia:

This brings [Aleksandr] Khramchikhin back to China. He has previously written some fairly alarmist pieces about the potential Chinese threat to Russia, so this time he focuses on the possibility that China would attack Kazakhstan. This seems to be a sufficiently fantastic scenario that it could be dismissed out of hand, but instead he argues that China would easily win such a conflict while absorbing Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan with minimal effort. This means that Russia would have to come to Kazakhstan's assistance or face the prospect of a 12,000km border with China stretching from Astrakhan to Vladivostok. (I'm not sure what happens to Mongolia in this scenario, but I assume it's nothing good.) And at this point, Khramchikhin argues that Russia might as well capitulate on the spot.

I suppose this is like how if Communists take over South Vietnam next thing you know they'll be running Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and probably Australia and Japan to boot.

I would say that one of the major lessons of the past fifty years has to be that it's extremely difficult to coercively dominate foreign populations who have nationalist objections to your rule. It's not impossible, but it's damn hard and the government of China would need to be pretty crazy to want to try to govern Kazakhstan. Crazy things do happen—look at Iraq—so I don't think it's totally safe to assume that the Chinese won't ever do anything crazy. But part of the craziness of any course of action along these lines is that Russia would have any number of low-cost ways to make things difficult for China by sending supplies and weapons across the very long and hard to police Kazakh-Russian border.

Much like with the idea that the Taliban somehow poses a threat to Russia, there just seem to be a group of people in the Russian security establishment who really want to be involved in the former Soviet Republics. This desire is leading them to hallucinate a whole host of possible threats.

I really enjoyed Peter Hopkirk's book, The Great Game, about Anglo-Russian imperial conflict in 19th Century Central Asia. But the bottom line is that this is a part of the world that contains very little of value. The ultimate fates of the British and Romanoff Empires were ultimately determined by factors that had nothing to do with Central Asia, and the bad habit a whole series of great powers fall into in this region is simply wasting resources.

Hillary Says No 2016 Bid

Just when I was hoping that Barack Obama's midterm setback would lead to a surge of dumb speculation about a Hillary Clinton 2012 primary challenge, she goes and ruins everything by telling a television station in New Zealand that she won't run even in 2016.

I wonder if she'll reconsider this. Assuming she doesn't, I think we ought to learn the lesson from 2008 that even though women face formidable barriers at earlier stages of the political process a credible woman candidate has a very good chance of winning a Democratic presidential nomination. Woman make up a clear majority of the electorate in Democratic primaries, but most Democratic politicians are men. Actual voting behavior indicated the existence of large gender gaps that basically left Hillary Clinton with the bigger half of the party. Barack Obama was able to overcome this because he appealed to African-American women and twentysomething women, but the list of people who could replicate that seems very short. What's more, Obama had a great primary campaign issue in the form of the war.

The process through which a person comes to be deemed a viable presidential candidate is fairly mysterious, but my point is that if a few movers and shakers do find a woman governor, senator, or cabinet member to start coalescing around she'd have formidable advantages against a field of male opponents.

The Mechanics of Monetary Policy

(cc photo by LateNightTaskForce)

I almost want to encourage people not to read Felix Salmon's excellent post explaining the mechanics of quantitative easing because the truth (you print money and give it directly to big banks) is ugly and would probably undermine support for a measure that I think would be useful. But instead what I'll observe is that one of the biggest differences between "quantitative easing" and old fashioned regular easing is precisely that by convention journalists never explain how regular monetary policy works. What you hear is that the Fed decided to "cut interest rates." But there's not an interest rate switch behind Ben Bernanke's desk that he flips toward cut.

Instead what happens is something very much like what Salmon describes in the QE scenario. The Fed decides that it wants short-term rates to fall and then takes the specific action of buying short-term bonds from major securities dealers. With QE2 all that's changing is that they're going after slightly longer-term bonds.

The only real difference here is a difference in degree. But the press tends to describe it as a difference in kind, contrasting "interest rate cuts" from "bond purchases" but in both cases you're buying (or selling) bonds in order to cut (or raise) interest rates. Like it or not, this is how we conduct monetary policy in the United States and nothing about going bigger or smaller with quantitative easing is going to change that.

As it happens, I don't like that idea a huge amount at this point. I think what we should be looking to do is to give the money directly to households. Instead of creating money and using it to buy $600 billion in bonds, create money and use it to send $2,000 to each American. That's an approach that would be superior from a humanitarian standpoint even if it didn't ultimately produce macroeconomic gains, and it would also have more political legitimacy.

Alternatively, if you want to talk about something that does look to me to be a useless giveaway to banks, consider the Fed's habit of paying interest on "excess reserves." This is counterproductive to the Fed's goal of injecting more money into the economy (since reserves held at the Fed are not in the economy) but it's a way of delivering extra profits to banks as a way of covertly recapitalizing them.

EPA Regulation and the New Congress

It seems to me that the only way for Barack Obama to avoid going down in history as something like the Zachary Taylor of the climate change era is to stand firm on the EPA's legal obligation to regulate carbon dioxide emissions and to marshall forty Senators who refuse to agree to legislation or amendments that would entail de facto repeal of the Clean Air Act. The administration should state clearly that it agrees that Clean Air Act regulation isn't the optimal approach to this issue, and should reiterate that this is why it's been willing to support a variety of alternatives. But it, along with a bloc of climate hawk senators, needs to insist that any alternative to the existing Clean Air Act framework be a real alternative that does in fact lead to reductions in harmful greenhouse gas emissions.

Other ideas, such as increased energy R&D, renewable electricity standards, subsidies for nuclear power or "clean coal" or what have you may or may not have merit in isolation, but none are a substitute for emissions reductions. Possibly Lisa Jackson should hang a giant banner of F.A. Hayek's case for air pollution regulation on the side of the EPA building.

I largely agree with the strain of analysis that says a carbon pricing scheme can only be implemented via a bipartisan legislative process. And as the Hayek point illustrates, there is literally no reason why fans of free markets or limited government should be possessed with blanket opposition to emissions reduction schemes. What's needed is a strategy of building political power to the end of bringing people back to the table. And the only way to do that is to make the status quo bias of the American government work for us. As long as the Obama administration sincerely wants to avoid caving on Clean Air Act regulation there's very little chance the GOP can make them cave. Unfortunately, so far the White House seems lukewarm. That needs to change. A pure regulatory approach to this problem is not very well-regarded among wonks, but it's extremely popular with the general public. And if implemented in a serious way, it should bring a variety of interests back to the table to talk about price-based alternatives.

Jobs

151,000 new jobs in October, unemployment rate flat. Once again a positive number that's consistent with the employment/population ratio never rising. Something to note—that I'll look at in greater detail—is that for months now we've been getting the economy that conservatives claim to want. The private sector is growing and the public sector is shrinking. The net result of this is very tepid job growth, which is precisely why liberals have been saying it would be a bad result. But conservatives who've been saying we're wrong about that have no right to complain about the ugly nature of the results. The fact of the matter is that attempting to undertake a substantial structural shift out of public sector employment in the middle of a recession is painful and insane. But it's what we're doing.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers