Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2505

November 8, 2010

The Dialectic is Interested in Climate Scientists

I'm very much in agreement with Dave Roberts about the ultimate futility of any effort to "keep the politics out" of climate science:

Curry may be able to remain scrupulously apolitical, if that's her inclination. But climate science in general cannot escape politics. Not because scientists — or the advocates and politicians who take it seriously — did anything to bring it on themselves. It's just that an alliance of energy incumbents and far-right ideologues has chosen to lie relentlessly about it. In the milieu of current climate and energy politics, speaking the truth is a political act. The only way to escape politics is to lapse into silence.

That's moralized language. A different way of putting it would be à la Trotsky's quip that you may not be interested in the dialectic, but the dialectic is interested in you. It's possible to have meaningful dialogue about an issue on a technical "non-political" level if and only if the political system isn't interested in the question. In the early part of the decade, monetary policy was a "non-political" issue and Ben Bernanke could float quantitative easing at conferences and a bunch of guys with PhDs would discuss it calmly. Today it's different. Monetary policy makes headlines, Mike Pence issues press releases denouncing QE, Sarah Palin offers her take on Twitter, etc.

That's life. I understand that people don't like it. Personally I prefer talking about issues that aren't at the forefront of national politics. I've had great conversations over the past year about postal banking with people who are considerably more leftwing than I am and with people who are considerably more rightwing than I am. That's because obviously America isn't going to institute a postal banking system in the short-term, so it's a pleasant non-partisan conversation. So I definitely sympathize with the desire of scientists working in the climate space to stay "out of politics." But politics is interested in climate science! A lot of policymakers have looked at the science and drawn the conclusion that a dramatic policy response is warranted. A dramatic policy response, however, upsets many stakeholders who have a vested interest in attacking both the policy inference and the underlying science.

The Secret War on Poverty

Annie Lowrey did an excellent piece last week about the weird way in which poverty has vanished from the American policy agenda even as the 111th Congress in practice passed tons of legislation favorable to poor people:

In the just-finished campaign, as usual, every candidate claimed to be standing up for the middle class. Democrats argued that they delivered what the middle class needed: tax breaks, health care reform, and federal aid to states to help ease the recession. Republicans argued that Democrats failed to deliver the only thing the middle class wanted and needed: jobs. Neither party talked much about "low-income families," to use the preferred euphemism—or, more bluntly, poor folks.

In truth, the Congress of the last two years passed more legislation benefiting the poor than any other in memory. That the Democrats didn't campaign on their achievements may indicate one of two things. One, poor folks—unlike, say, politically generous Wall Street bankers or socially conservative Rust Belt Catholics—are generally not viewed as a constituency worth courting. Two, as with the stimulus bill's effect on unemployment, what the Democrats did mainly consisted of preventing a bad situation from getting worse.

The total inattention to the issue of poverty during the current recession by the "sensible center" is, meanwhile, quite damning. During the 1980s the notion that work, rather than relief programs, was the only road out of poverty gained a lot of steam. And in 1995 that principle was enacted into law as part of the Clinton-Gingrich welfare reform. And as long as the economy stayed near full employment the new policy paradigm worked. The whole thing was proclaimed a success and the left (as always) was proclaimed to have been discredited.

But anyone who cared about this agenda at all as a matter of substance would be lighting their hair on fire over the prospect of a years-long period of 7+ percent unemployment. After all, if you replace income-supporting programs with work-supporting programs you're implicitly undertaking an obligation to provide the demand for labor that would ensure the availability of jobs. And yet somehow I don't see "centrists" out there slamming Ben Bernanke for sabotaging welfare reform to reassure inflation-panickers or calling for congress to enact massive public works programs.

But which is it? Are people supposed to work or aren't there? If it's the former, you need to provide jobs for low-skilled people to do.

The Luck of the Irish

Here's Chris Edwards, director of tax policy at the Cato Institute and author of Downsizing Government writing at National Review online in March 2007 about how everyone would be more like Ireland if only they listened to rightwing economic policy:

Ireland has boomed in recent years, and it now boasts the fourth highest gross domestic product per capita in the world. In the mid-1980s, Ireland was a backwater with an average income level 30 percent below that of the European Union. Today, Irish incomes are 40 percent above the EU average.

Was this dramatic change the luck of the Irish? Not at all. It resulted from a series of hard-headed decisions that shifted Ireland from big government stagnation to free market growth. After years of high inflation, double-digit unemployment rates, and soaring government debt that topped 100 percent of GDP, Irish policymakers began to cut spending in the late 1980s in a desperate bid to recover financial stability.

Irish government spending fell from more than 50 percent of GDP in the 1980s to 34 percent by 2005. For Europe that is a triumph of restraint, given that the average size of government across 25 EU countries today is 47 percent of GDP. And Ireland has steadily reduced its tax rates. The top individual income tax rate was cut from 65 percent in 1985 to 42 percent today. The capital gains tax rate was cut from 40 to 20 percent in 1999.

However, the key to Ireland's success has been its excellent tax climate for business. In 1980, Ireland established a corporate tax rate for manufacturing of just 10 percent. That low rate was subsequently extended to high-technology, financial services, and other industries. More recently, Ireland established a flat 12.5 percent tax rate on all corporations — one of the lowest rates in the world, and just one-third of the U.S. rate.

James D. Gwartney and Robert Lawson writing for Cato back in 2005 said that Ireland should be seen along with Iceland as an important case study in the success of free market economics.

Today of course Ireland is a total disaster. I wouldn't try to blame their property crash on low tax rates. But by the same token a frightening number of pundits went "all-in" on the idea that Ireland's conserva-friendly tax policies were behind a boom that was in fact driven by a real estate bubble. There needs to be some accountability for this, because it appears to quite genuinely be the case that relaxed financial regulation is a can't-lose strategy for (temporarily) attracting financial inflows, sparking an asset price bubble, and boosting growth. But that doesn't mean countries should do it. And we need a system of international praise and esteem that's not so blind to these issues.

Obama Backs Security Council Seat for India

I'm glad to see Barack Obama announce support for giving India a Security Council seat. Reform of the UN Security Council is something of a doomed endeavor, but in my view that's all the more reason for the United States to play the role of good guy rather than protector of the status quo. India and Japan should have permanent Security Council seats. Brazil too. We should work something out with Africa. The EU should have some kind of consolidate seat instead of separate ones for France and the UK. There shouldn't be unilateral vetos of UNSC resolutions. The "Forging a World of Liberty Under Law" report from John Ikenberry and Anne-Marie Slaughter (currently at the State Department) had a lot of good ideas along these lines.

Will it happen? Not in the short-term, that's for sure. But let China and France be the spoilers here.

Over the long run, either these structures will shift or else they'll become decreasingly relevant. The former would be clearly preferable to the latter, but in either case it makes sense for the United States to try to get ahead of the curve.

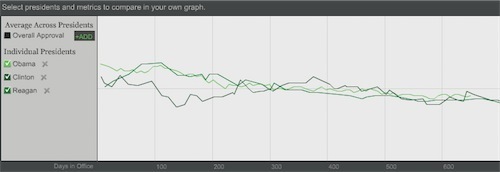

Obama Approval in Context

Lowell Feld brings some much-needed perspective to the future predictive value of Barack Obama's currently mid-forties approval rating. Here's Gallup's comparison of Obama to some other recent presidents:

I don't think progressives should draw false comfort from this. The mere fact that Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton had substantial political recoveries doesn't make an Obama turnaround inevitable. And both Reagan and Obama were substantially hampered in their last six years in office by the presence of an opposition congress. Nevertheless, both men did turn their public approval ratings around and both men passed important pieces of bipartisan legislation even after losing control of congress.

The point is that nobody now looks back on 1982 and says "well, conservative overreach killed the right for a generation." Instead it's more like "conservatives changed a bunch of stuff then suffered a setback and there's was some retrenchment but still the country was never the same."

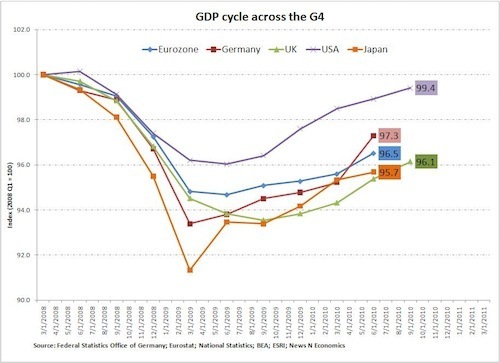

Europe Under Pressure

Bad as the American economy is doing, the picture in Europe is really a good deal bleaker as this Rebecca Wilder chart indicates:

Germany is having more of a classic rebound recovery than we are (and their kurzarbeit plan worked pretty well to help people weather the storm), but it's from a much sharper downturn. And much of the rest of the EU is looking disastrous. When the single currency area was formed, skeptics warned that it would prove unworkable amidst this kind of crisis to yoke very dissimilar economies together into one monetary system. And as Ryan Avent observes there's little indication that the main Euro-area governments wants to take the steps that would be necessary to make the system work:

Something clearly has to give. Policy changes are pushing Europe toward a very long period of stagnation if not an outright return to recession. Workers are underemployed and furious. Core and periphery have seriously diverging views on the direction policy should take. And markets continue to pressure indebted nations to make cuts they may not actually be able to make.

Either the ECB must seriously soften its stance, or Germany and France must suddenly become much more generous to struggling euro zone economies, or the euro zone will face its toughest months yet. If no exit valve for the building pressure can be found, then pressured economies will begin heading for the exits.

It's worth recalling that America's recovery turn a turn for the worse starting with a period of concern around Greece and the Euro. We finally got a single decent month of jobs numbers, but people shouldn't forget that there are still tons of problems lurking in the global economy.

When Do Deficits Matter and Why

I was challenged yesterday as to whether my pro-stimulus views mean I think that "deficits don't matter." On the contrary, belief that running a fiscal deficit during an economic downturn can be a useful tool of macroeconomic policy is part and parcel of the belief that deficits do matter and that contrary to the practice of the Ronald Reagan and George W Bush administrations we should not run large structural deficits over the course of the business cycle.

But the question is: What about deficits matters? You often hear deficits discussed as a kind of morality play. Government should "live within its means," whatever that means. Or else you hear conservatives—who don't care even the slightest bit about deficits—complain about "deficits" when what they mean is "spending when a Democrat is in the White House."

In the real world, though, deficits matter for a specific reason. If the government tries to borrow a huge amount of money, investors will start demanding generous interest rates in exchange for lending. And if investors can get high rates lending to the government, which is safe, they'll start demanding even higher rates of non-government borrowers. That becomes a problem for the private sector. Investments that are profitable at a low rate of interest are unprofitable at a high rate of interest, so the overall pace of investment and growth declines. Bad. The Federal Reserve can, however, act to keep interest rates low. The problem with this is that Fed action to lower interest rates might produce too much inflation. Inflation, when it gets high, is not just annoying but starts to really erode the workings of the price system and thus the whole economy. Again: Bad.

But those are specific reasons. We're not currently in a situation where Fed action to keep interest rates low is producing an undesirably large quantity of inflation. Inflation is currently below two percent and has been below two percent for a while. So there's not currently any problem with running a large deficit. On the contrary, we have a problem whereby a large number of able-bodied adults and other potentially valuable resources are lying idle.

Something to consider to test your intuitions about deficits is to consider the case of a country that has no national debt. During the upswing this country (call it "Norway") has been running budget surpluses and building up a nest egg. Then—bam!—a recession hits, and tax revenues fall below what's needed to finance government programs. In this situation I think it's very intuitive that the right thing to do is to spend down the nest egg for a year or two rather than add to people's problems with higher taxes or reduced spending. It's unfortunate that America wracked up a giant debt load in the 2000s rather than staying on the late-nineties trajectory, but that unfortunate fact doesn't alter the basic logic fiscal logic of a downturn.

November 7, 2010

Meg Whitman

Now that the campaign's been over for a while can we all step back and ponder how nutty it was for Meg Whitman to spend $140 million on a failed bid to become Governor of California? That's a lot of money. And if you spent that kind of money on philanthropic pursuits, you'd be a very powerful and influential person. If you're determined to exchange personal wealth for prestige and power, bankrolling your own political campaign seems like a very bad way to go about it.

At any rate, my advice to rich businesspeople who want to get into politics would be to aim lower. Self-finance a campaign for Mayor or State Treasurer or something. Try to do a good job. And then parlay your vast wealth into a leg up in your run for a major office. Politics is difficult. People who've run successful statewide campaigns in the past have real skills that money can't easily substitute for.

Tax Dollars Going to Subsidize Cheesier Dominoes Pizzas

I wrote about this once before, but the scandal of America's taxpayer-subsidized initiative aimed at getting people to eat more cheese has made it to the New York Times:

Then help arrived from an organization called Dairy Management. It teamed up with Domino's to develop a new line of pizzas with 40 percent more cheese, and proceeded to devise and pay for a $12 million marketing campaign.

Consumers devoured the cheesier pizza, and sales soared by double digits. "This partnership is clearly working," Brandon Solano, the Domino's vice president for brand innovation, said in a statement to The New York Times.

But as healthy as this pizza has been for Domino's, one slice contains as much as two-thirds of a day's maximum recommended amount of saturated fat, which has been linked to heart disease and is high in calories.

And Dairy Management, which has made cheese its cause, is not a private business consultant. It is a marketing creation of the United States Department of Agriculture — the same agency at the center of a federal anti-obesity drive that discourages over-consumption of some of the very foods Dairy Management is vigorously promoting.

Except for the fact that their pizza is bad, I don't particularly think it's worth giving Dominoes an especially hard time about their nutritional practices. Their nutritional calculator page is very handy (though the assumption that you're eating just one slice is a bit unrealistic) and many eateries leave you totally in the dark about this stuff. But there's just no need whatsoever for a government program of this sort.

And that, to me, is what's frustrating about a lot of the recent conversation around "government spending" and "are public employees paid too much." When the government is doing something useless or harmful that it shouldn't be doing at all then there's no salary or pension level at which public employees or government contractors are delivering value to the American people. If you've got a worthwhile public function, it's foolish to undermine it by being stingy about spending. But there's a fair amount of stuff like this in the budget that we could entirely do without. I'd like to think that the new Republican Congress' budget cutting zeal will give us a chance to re-examine some of these programs, but realistically I think we'll find that implicit and explicit subsidies to US producers of this sort continue to find favor.

The Misinformation That Matters

Evan Bayh thinks "Democrats should support a freeze on federal hiring and pay increases. Government isn't a privileged class and cannot be immune to the times."

Steve Benen asked a good question about this:

Reading this, I'm wondering, "How would that help the economy?" Bayh is arguing that we'd be better off if fewer unemployed workers get jobs and federal workers have less money. I'm sure he can explain why this would help the economy — and I'm sure it's very "moderate" — but I have no idea what that explanation might be.

I think that Bayh is probably operating with an explicit model of the economy as a closed zero-sum system. A recession is a negative shock leading to bad times. Policymakers then have the opportunity to influence the course of the recession by allocating the badness around. Failure to cut public sector compensation creates a "privileged class" and increases the quantity of pain felt by people outside that class, whereas ensuring that members of that class experience pain reduces the pain felt by others.

My view is that the Bayh Model is mistaken. Of course the primary losers in Bayh's plan will be those whose incomes are directly reduced. But individuals will respond to reduced income by reducing spending, and those reductions in spending will reduce everyone else's income. My model of the economy isn't a zero sum system. In my version, a typical recession is a needless waste of resources—unemployed workers, vacant storefronts, empty offices, idled factories—and public policy actually impacts the extent to which resources are wasted and the pace at which they're put back into use.

I think the primary political problem progressives have had over the past two years stems from the fact that our accurate account of the recession is less believed than Bayh's inaccurate model. I think virtually all Republican members of congress and many Democratic members of congress embrace the Bayh Model. And I think this is how it goes throughout the ranks. From ordinary citizens to campaign operatives to Hill staff to reporters etc. The Bayh Model had common sense on its side, most people are not specialists in the subject, and I think most non-specialists believe in it. They think that being hit by a recession is like being hit by a hurricane or a drought. It's something that causes a temporary period of intense suffering that can be managed well or poorly but primarily has to be endured. Common sense views "fiscal stimulus" (whether for good or for ill) as a form of humanitarian disaster relief, and common sense views Bayh's pain-sharing proposal as reasonable, and common sense doesn't think about monetary policy at all.

I think all this is mistaken and recessions are quite different from hurricanes. But I think that progressives have tended to focus too much on "crazy person misinformation" (Obama is a secret Muslim, Obama spent nine trillion dollars on a trip to India, Obama is from Kenya) and not enough on "common sense misinformation" of the sort Bayh is expressing. The widespread nature of common sense misinformation about the nature of recessions—not just among low-information voters but even among political professionals and policy elites—has been a huge drag on macroeconomic performance and that in turn has dragged down the entire progressive agenda.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers