Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2470

December 14, 2010

Third Parties

After reading Matt Bai on Michael Bloomberg's prospects as a third party presidential candidate along with various recent commentary about the idea of a from-the-left challenger to Barack Obama, I'm coming to the view that too much of this kind of talk focuses on the actual viability (or lack thereof) of possible third party runs. What's more interesting to me is all the ways that non-viable candidates can make a difference.

After all, it's reasonably common in recent years for an incumbent or quasi-incumbent center-left party leader to succeed in capturing the median voter and nonetheless lose power in the face of many people voting for further-left candidates. That's how Al Gore lost, that's how Paul Martin lost power in Canada, that's how Gerhard Schöder lost power in Germany, and it's arguably the reason Lionel Jospin couldn't beat Jacques Chirac for the Presidency of France. In all these cases, I think the Nader/NDP/Linke/Trotskyite voters were being short-sighted and counterproductive. But the point is that these things happen. A lot of people all around the developed world are basically pacifists and fundamentally don't accept the neoliberal economic consensus. And there's basically no way for a center-left movement to win without getting the votes of that constituency, even though few mainstream center-left political leaders (and certainly not Barack Obama) actually espouse those views.

The resulting problem of coalition management is both big and quite difficult. It's something worth paying attention to even though the idea of a third party candidate winning the presidency or of a primary opponent beating Obama is silly.

Progressive Institutions Rally for Senate Reform

I'm very heartened to see a coalition of progressive groups send a letter (PDF) outlining some Merkley/Udallish ideas about Senate procedure:

We ask Senators to move forward with reforms consistent with these eight principles:

1. On the first legislative day of a new Congress, the Senate may, by majority vote, end a filibuster on a rules change and adopt new rules.

2. There should only be one opportunity to filibuster any given measure or nomination, so

motions to proceed and motions to refer to conference should not be subject to filibuster.

3. Secret "holds" should be eliminated.

4. The amount of delay time after cloture is invoked on a bill should be reduced.

5. There should be no post-cloture debate on nominations.

6. Instead of requiring that those seeking to break a filibuster muster a specified number of

votes, the burden should be shifted to require those filibustering to produce a specified number of votes to continue the filibuster.

7. Those waging a filibuster should be required to continuously hold the floor and debate.

8. Once all Senators have had a reasonable opportunity to express their views, every measure or nomination should be brought to a yes or no vote in a timely manner.

All good points. I think it's a little bit silly that we live in a country where simply stating that the United States Senate should vote by the same majority rules process as is used by the House, the Maine State Senate, the German Bundesrat, the House of Lords, the Top Chef judges, the Electoral College, the Supreme Court, and just about every other institution is considered too radical. Still, these would be important steps in the right direction.

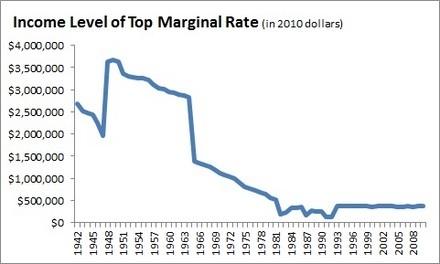

Who Pays When "The Rich" Are Taxed?

Paul Waldmann produces a very interesting chart which illustrates that not only have the top marginal headline tax rates declined over time, the :

This is a difficult to justify response to a world in which there's more dispersion of incomes at the very high end than their used to be. More tax brackets would be a welcome development. Indeed, thanks to the widespread available of computers these days it should be possible to entirely dispense with the idea of "brackets" and express the rate as a continuous function of taxable income or consumption or whatever it is you want to use as the tax base.

The Political Economy of Land Use Regulation

Christian A. L. Hilber and Frédéric Robert-Nicoud give us "On the Origins of Land Use Regulations: Theory and Evidence from US Metro Areas"

We model residential land use constraints as the outcome of a political economy game between owners of developed and owners of undeveloped land. Land use constraints benefit the former group (via increasing property prices) but hurt the latter (via increasing development costs). More desirable locations are more developed and, as a consequence of political economy forces, more regulated. Using an IV approach that directly follows from our model we find strong and robust support for our predictions. The data provide weak or no support for alternative hypotheses whereby regulations reflect the wishes of the majority of households or efficiency motives.

If Mark Warner is really concerned about the impact of regulation on economic growth, he might want to start talking about this stuff instead of just talking in general terms about the need to "address the regulatory uncertainty felt by many of our small and large businesses."

Labor Market Regulation and Innovation

Viral V. Acharya, Ramin P. Baghai, and Krishnamurthy V. Subramanian buck the conventional wisdom and stand up for labor market rigidity:

Stringent labor laws can provide firms a commitment device to not punish short-run failures and thereby spur their employees to pursue value-enhancing innovative activities. Using patents and citations as proxies for innovation, we identify this effect by exploiting the time-series variation generated by staggered country-level changes in dismissal laws. We find that within a country, innovation and economic growth are fostered by stringent laws governing dismissal of employees, especially in the more innovation-intensive sectors. Firm-level tests within the United States that exploit a discontinuity generated by the passage of the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act confirm the cross-country evidence.

I normally consider myself a member of the pro-flexibility neoliberal consensus that making it hard to fire people makes it unduly difficult for people to get jobs in the first place. But this is a very interesting result for the other side and I'd love to see the issue further examined with some other proxy tests for innovation.

China's Dangerous Lower Middle Class

The other point I wanted to make yesterday was about the political risk to the Chinese regime posed by disappointed college graduates:

While some recent graduates find success, many are worn down by a gauntlet of challenges and disappointments. Living conditions can be Dickensian, and grueling six-day work weeks leave little time for anything else but sleeping, eating and doing the laundry.

But what many new arrivals find more discomfiting are the obstacles that hard work alone cannot overcome. Their undergraduate degrees, many from the growing crop of third-tier provincial schools, earn them little respect in the big city. And as the children of peasants or factory workers, they lack the essential social lubricant known as guanxi, or personal connections, that greases the way for the offspring of China's nouveau riche and the politically connected.

Back in the 1990s it was often fashionable to argue that increased prosperity would magically transform China into a more liberal political system. Today, that's clearly not the case. What we're seeing here, though, is the more likely mechanism for political change—dashed hopes. Peasant farmers often just feel beaten-down and resigned to their fate. But these are the would-be upwardly mobile. People who know perfectly well that better economic opportunities are possible and thus are poised to develop complaints and resentments.

As long as China maintains the world's fastest-growing economy, it's hard for me to imagine political dissidence gaining any kind of toehold. But if the PRC leadership can't continue delivering the goods, these are the kind of people likely to turn into big time troublemakers.

The Debt Ceiling Showdown

Apparently Harry Reid thinks it's a good thing that the tax deal doesn't include an increase in the debt ceiling. I think Reid's dead wrong about that. Already we see Bob Corker "hoping to assemble a bloc of senators who will demand tax and spending reforms" and I'm guessing that zero percent of the people he gathers will see any contradiction between voting in favor of a huge increase in debt and being reluctant to authorize an increase in the debt ceiling.

But my advice to progressives who don't like the tax deal would be make sure they do some hostage-taking of their own on the debt ceiling. You don't want a scenario in which the narrative is about how "Corker and blah blah" are reluctant to vote yes.

It Only Counts If Your Party Cares

(cc photo by kevindooley)

Duncan Black: "I can instantly invoke, sadly, a looped memory of Cokie Roberts uttering what was the beltway chant at the time, 'up or down vote up or down vote up or down vote up or down vote up or vote,' a phrase which only appears to be operative when Democrats control the Senate."

I sympathize with this, but I think this is an instance of blaming the media for what's really a problem of political leadership. Barack Obama and his administration have made very little effort to stigmatize filibustering. Nor have the key members of the Democratic caucus in the United States Senate. Harry Reid has only mildly flirted with criticizing filibustering, moderates have strenuously opposed the use of the budget reconciliation process to pass key legislation, and in general Senate Democrats have spent the majority of the 111th Congress seeing the filibuster as a key tool for their own empowerment.

It's been great to see a handful of newer Senators—most notably Jeff Merkely and the Udalls—take the lead in pressing for reform. But any time you see very junior senators taking the lead on something, the negative space speaks volumes. The effort to deligitimize anti-Bush filibusters was led by Majority Leader Bill Frist and President George W Bush, not by backbenchers.

Interest Rates and Recovery

Sewell Chan of the New York Times is one of the top economic reporters out there. But one of the costs of traditional journalism is that you need to be too kind in your assessment of important people so that they'll continue to cooperate with you. And I think this interesting but far too nice profile of Kansas City Fed Chairman Thomas Hoenig is a case in point. The main thing I think you need to know about Hoenig as a monetary policy thinker is this. He's been a Fed President for 20 years. And he's been an inflation hawk for 20 years. However much the mainstream is worried about inflation, he worries more.

And in those 20 years, he's never been right. We've never had an episode of undesirably high inflation. And we've had several episodes of business cycle recession. A stopped clock is right twice a day, and Hoenig is right zero times in a twenty year span. Zero. It's a bad record. People shouldn't listen to him. But the only thing in the article that I think might actually mislead people is this:

A month after the Fed announced its intentions to buy bonds and push down interest rates, investors have done the opposite by driving up long-term rates, hardly a help to a sputtering recovery.

This is a bad form of reasoning. Think about a commodity like oil. More robust recovery would increase the demand for oil, thus raising oil prices. And ceteris paribus, higher oil prices would be a drag on recovery. So if we implement pro-growth measures, that's likelly to raise the cost of oil—but that doesn't mean the pro-growth measures are in fact anti-growth. The interest rate trajectory is the same. What's happened in the past month is that growth expectations have increased, and that's reflected in slightly higher interest rates. Hoenig was wrong again. It's true that those slightly higher rates are, ceteris paribus, a drag on growth. But that just goes to show that the Fed should do even more monetary easing and should keep easing until inflation expectations show a problem. As of now, they're still anchored below two percent. It's true that if we do that Hoenig will complain about inflation, but that'l just be another example of his unfailing wrongness about monetary policy.

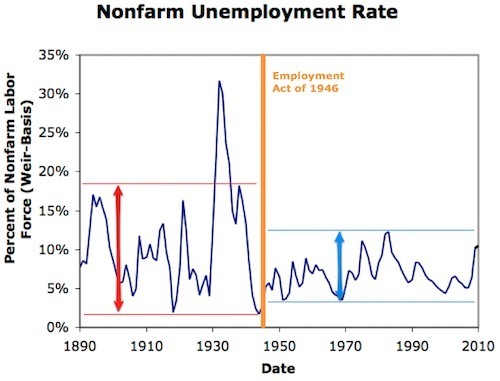

Before and After Macroeconomic Stabilization

Brad DeLong makes the case that despite the failures of current macroeconomic stabilization policy, you can still see that we're doing this much better since World War II than we did before:

This is worth noting because it's always worth pushing back against a certain kind of passive fatalism that becomes fashionable in bad times. History is a long game. As bad as the problems of the 2010s are, they're not as bad as the problems of the 1930s or the 1890s. By the 2050s, the world will still have problems but there's reason to believe that with hard work and determination we can make that a much better world. The 2050s are a long way off, of course, but in a world with a median age of 28 a great many of us will hopefully still be alive by that time.

I mention this because around the office not everyone is as convinced as I am by the merits of this tax deal. But I'm convinced because, fundamentally, I'm a real believer in macroeconomic stabilization policy. If it were up to me, I'd much rather see the deficit increased via infrastructure investments and other good stuff instead of tax cuts, many of them regressive. But I also do think that in a world of nearly ten percent unemployment job number one of the President should be to find the Maximum Politically Feasible Fiscal Stimulus and this deal seems like a decent approximation of that. If lefties want to try to hold out for a better deal, that seems non-outrageous to me, but what I would hold out for is even more stimulus rather than smaller tax cuts.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers