Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2471

December 14, 2010

Monetary Policy Since the Great Inflation

(cc photo by LateNightTaskForce)

Allison Schrager's defense of central bank independence seems like an excellent occasion to launch an argument I've been cooking up. She concludes with this:

It's fair to question how independent and long-term minded the Fed really is. In the last few decades the Fed was quick to aggressively cut rates during a recession to prop up a flailing economy. Yet there existed an asymmetry with this policy. When the economy grew very fast the Fed did not increase rates to match. It suggests central bankers (who know better) wanted to provide an economy with all upside and no downside: like politicians. Nonetheless, even if flawed, Fed independence remains a crucial component to a healthy economy. We saw this week how hard it is to push even mildly stimulative fiscal policy through Congress. You can you imagine what would happen if we let them have a direct hand in monetary policy too.

But okay. Say we start in 1980 and try to draw a list of times developed economies have fallen into recession. Call this the "too tight" list. Now lets try to draw a list of times developed economies have had bouts of inflation. Call this the "too loose" list. The too tight list is going to be way, way, way, way longer than the too loose list, which I believe would consistent almost entirely of France in the early Mitterand years.

I think it's perhaps time to consider the possibility that monetary policy has been systematically too tight in the developed world for the past 20 years. I think it's pretty commonplace to observe that policy in general tends to kind of swing form overreaction to overreaction. So in the 1930s we had a Great Depression. That led to an expansionary bias that led to a Great Inflation in the 1970s. It seems plausible to think that the pendulum swung in reaction toward unduly tight policy. And what would we expect to see if policy had become too systematically too tight? Well, we'd expect real GDP growth to slow down relative to where it had previously been (check), we'd expect working class wages to stagnate (check), and we'd expect to see countries with less inflation to also experience slower real growth, which is exactly what you see if you compare the US to Europe to Japan.

The political right is normally associated with argument for tighter money, of course, but I think conservatives should consider embracing this conclusion. For one thing: I think it's true. For another thing, if it's true then it provides a solution to middle class wage stagnation that's much, much, much more "free market" than the alternatives you're likely to hear from Jacob Hacker, Paul Pierson, Paul Krugman, Bernie Sanders, etc.

December 13, 2010

Endgame

I ain't coming back:

— Lukasz Gottwald's is credited on 10 percent of Billboard's 100 biggest hits of the year.

Highway Terror

Reader AS looked up the Bureau of Transportation statistics data and did a calculation for me:

In the US, 583 billion passenger-miles were flown in 2008, the most recent year available (I think I can mix numbers from '08 and '09 without loss of generality). So if all that travel was done by car instead (obviously not feasible) with a fatality rate of 11.35 deaths per billion miles, we'd expect an increase of 6,617 deaths. In other words, terrorists would have to blow up 16 full 747′s a year (about one every three weeks) to make air travel as dangerous as car travel. I think that number gets at the point you were trying to make about the exaggerated scale of the threat of aviation terrorism.

I don't think this is necessarily a point about how we should care less about aviation terrorism. But it is a call to try to think more rigorously and systematically about transportation security. I'm of the view that we under-emphasize the importance of reducing automobile-related fatalities in the United States. But it's also true that driving a car, while quite dangerous, is also very useful. So faced with a proposal to make driving safer we do try to trade it off against both direct financial costs and reduced convenience. A well-enforced nationwide speed limit of 50 miles per hour would save a lot of lives but it would also have a lot of downsides.

Air travel should be regarded similarly. We obviously have an interest in making it safe to fly in airplanes. But we also have an interest in making it fast and convenient to fly in airplanes. Currently flying in airplanes is dramatically safer than driving a car. Under the circumstances, only measures with a very high ratio of increased safety to increased hassle really make sense.

Now obviously part of the issue here is that people are more upset about deaths caused by bad guys than deaths caused by "accidents." So fair enough. But plenty of automative deaths are caused by bad guys who are driving under the influence. And more broadly I would say that if we want to invest more money and energy in terrorism investigations in general that seems a lot more rational to me than specifically working on the problem of aviation safety. Hire more FBI agents. Do more language training. Whatever.

Privatize Parking Lots By Selling Them

A "parking lot" is basically just an empty piece of land set aside for cars and I don't think it really makes sense for government to be in the business of providing parking spaces at sub-market rates. So when I heard that New Jersey Transit might be "privatizing" parking lots near commuter rail stations that sounded like a decent idea to me. But what does it even mean to "privatize" a parking lot? Well it seems to me that the way you would put a parking lot into private hands would be to sell the land which might then be operated as a market-rate parking lot or else redeveloped into something else like transit-oriented housing or shopping.

What's actually being proposed for New Jersey, however, is something different. New Jersey is going to contract-out the operation of the parking lots. That might lead to more rational pricing of the lots in the short term, but it will only make the overall problem worse:

[R]ather than taking on entrenched suburban interests, we're just adding another layer of government dependents, this time of the monied corporate variety (bidders include KKR, Morgan Stanley, Carlyle, and JP Morgan). The land on which transit parking lots sit is uniquely positioned to be converted into dense development, and the only thing worse than sitting on the land would be for the agencies to sign away their rights to change that within the foreseeable future.

Right. Today's privately owned parking lot could be tomorrow's transit-oriented development. And today's publicly owned parking lot could be sold to a private owner. But a parking lot that's publicly owned by contracted out to a private operator is the worst of both worlds—a kind of publicly guaranteed, contractually obligated subsidy to parking and parking-lot operation.

Private land ownership is neither a new concept nor a radical one. If a public agency owns some land somewhere that it wants to privatize, the correct way to privatize it is to sell it thus generating some privately owned land. This shouldn't be hard. If it's the case that a parking lot is the most valuable use of the land, then private owners can figure that out.

Wage Compression in China

Andrew Jacobs' article on China's glut of college graduates is so good that I have two different, unrelated points I want to make about it. For today, point one is about income inequality:

But the supply of those trained in accounting, finance and computer programming now seems limitless, and their value has plunged. Between 2003 and 2009, the average starting salary for migrant laborers grew by nearly 80 percent; during the same period, starting pay for college graduates stayed the same, although their wages actually decreased if inflation is taken into account.

This is roughly speaking the kind of change that egalitarians would like to see for the United States. Wages for working-class people are rising, the proportion of the population getting "good jobs" in the professional sector is going up, but on average professionals' compensation is flat or even falling. Now maybe in an ideal world the Chinese economy would be growing even faster and professionals would be seeing wage increases on average, but slower than the working class wage gains. Either way, the point is that this "compression" pattern of economic outcomes is perfectly consistent with a handful of super-rich people getting even richer. Indeed, a bet that part of what we're seeing in China is that a few lucky entrepreneurs are assembling vast fortunes riding the growth wave to the top. Nevertheless, in a more sense the trends in China are toward upward mobility (from farms to factories, and from factories to service jobs) and more equality.

This is relevant to the United States, too, where the relationship between working class wage stagnation and explosive growth in tippy-top incomes is really less clear than people sometimes seem to me to think. Clearly expanding the growth rate and the economic opportunities at the bottom end should be a priority. But if that happens will super-rich hedge fund managers suddenly get less rich? I don't see it.

Risk Aversion

Robert Samuelson has an interesting column about the economic problem of risk-aversion:

The Great Recession's most worrisome legacy could be this common allergy toward risk-taking. Having underestimated risks in the bubble years, we may overestimate them now. Consider the shriveling of venture capital – a big source of money for high-tech start-ups. In 2009, venture capital funds received less than half the $35 billion they raised in 2007, and inflows in 2010 are running 27 percent below 2009 levels. The institutions (pensions, endowments) and wealthy individuals that provide venture capital have less money to invest and are less willing to commit it to chancy firms.

I would put this another way, though. The allergy toward risk-taking isn't a consequence of the recession, it's something that existed even beforehand. After the dot-com bubble and the Enron/Worldcom accounting scandals, people were looking for safe investments. And the selling part of housing (for ordinary households) and mortgage-backed securities (for big shots) was that this was supposed to be a basically safe non-speculative investment with a somewhat higher yield than a savings account or a treasury bond. That turned out to be an illusion, but it was a risk-averse pursuit from the beginning.

In Praise of Labels

It seems very plausible to me that there are a number of areas of policy in which the right ideas are ideas that are currently being espoused by neither party. I write fairly frequently about things like land use regulation, occupational licensing, carbon emissions taxes, monetary policy via "helicopter drops," and a host of other issues in which the best solutions aren't currently being embraced by either Democrats or Republicans. And that's why I prefer to be affiliated with a think tank rather than working in partisan electoral politics.

But when you look at something like the No Labels initiative you see not merely advocacy of some ideas that neither party is pushing, but the idea that partisanship itself is somehow a bad thing.

That, to me, is a big mistake. If you go to a store you'll find that a huge quantity of the goods on sale are labeled to indicate which brand makes them. There's a good reason for this. Normally, how much you're willing to pay for a good or service depends on the quality of the good or service in question. But there's no way to sample the quality of a can of soda without buying it first. So how am I to know whether or not I want to buy that can of Diet Coke? Well it's simple. I may not have had that can of Diet Coke before, but I have had many other cans of Diet Coke. And I can infer that the Coca-Cola corporation, having invested a great deal of time and money in building the Diet Coke band is going to make a good-faith effort to turn out a consistent product. That doesn't necessarily mean everyone will like the taste of Diet Coke. But it does mean everyone knows more-or-less what Diet Coke tastes like, and then they can make their soda-consumption choices in a coherent way.

A good party system works the same way. Look at the 1960 Presidential election and see what happens when partisanship doesn't work as a reliable signal. I don't believe that the 1960 electorate in Alabama and Georgia was more conservative than the electorate in Florida and Tennessee. And yet Alabama and Georgia voted for Kennedy and Tennessee and Florida voted for Nixon. That kind of thing makes politics more interesting for reporters and more lucrative for sundry lobbyists and dealmakers, but it was bad for America and it's genuinely not a coincidence that it was strongly associated with white supremacist rule over a huge swathe of the country. The rise of recognizable and coherent parties creates some challenges for American political institutions, but the correct response is to tweak the institutions not to spend time wishing for label-free politics.

Karzai and America

(State Department photo)

Rajiv Chandrasekaran's excellent article on the troubled American relationship with Hamid Karzai offers up a telling anecdote:

As he spoke, he grew agitated, then enraged. He told them that he now has three "main enemies" – the Taliban, the United States and the international community.

"If I had to choose sides today, I'd choose the Taliban," he fumed.

So there you have it.

It seems to me that there are kind of two ways to think about this problematic situation. One, which seems prevalent in the relevant military circles, is to see the Afghan government as posing essentially tactical problems. Their job is to "win," problems with the Afghan government are problems for the goal of "winning," and so the question is about how best to manage the relationship while pursuing the goal of a "win."

A different way of looking at it would be to say that these problems with Karzai and his government actually create different obligations and interests for us than might otherwise be the case. If the de jure government of Afghanistan were a really promising and awesome force that was having an insurgency problem and badly wanted the assistance of the United States of America, then I would say we have very compelling reasons to make good on past commitments and do our utmost to help out. But if Karzai doesn't really want our help and isn't interested in doing the things that we think need to be done, then the reasons for being deeply involved are much less compelling.

Production, Consumption, and Prosperity

David Boaz at the Cato Institute uncritically endorses an extremely foolish Steven Horwitz take on consumption versus production in recession-fighting:

One of the most pernicious and widespread economic fallacies is the belief that consumption is the key to a healthy economy. We hear this idea all the time in the popular press and casual conversation, particularly during economic downturns. People say things like, "Well, if folks would just start buying things again, the economy would pick up" or "If we could only get more money in the hands of consumers, we'd get out of this recession." This belief in the power of consumption is also what has guided much of economic policy in the last couple of years, with its endless stream of stimulus packages.

This belief is an inheritance of misguided Keynesian thinking. Production, not consumption, is the source of wealth. If we want a healthy economy, we need to create the conditions under which producers can get on with the process of creating wealth for others to consume, and under which households and firms can engage in thesaving necessary to finance that production.

I think people find this sort of logic compelling because it has the combination of sounding virtuous and tough-minded, but also aligns you politically with the interests of rich people and powerful business executives. It's a hard to beat combination.

But ask yourself, why does the focus on consumption become prominent during economic downturns? Well it's because in a modern economy downturns often occur absent any kind of negative shock to our productive capacity. It's possible for such shocks to occur. The US military reduced most of Japan's cities to rubble in 1944-45 precisely in order to cripple Japan's ability to produce things. Increasing Japanese prosperity over the next ten years was about re-creating that capacity. But the year 2008 wasn't in the distant past, we can remember what happened and didn't happen. No American cities were destroyed by nuclear weapons. No draught crippled our agriculture. People didn't suddenly forget job skills they'd had. What happened was a large negative shock to demand not an earthquake or a flood or a plague. I was there and so were you.

People talk about demand during downturns because in a downturn you have an unusually large number of unemployed people. That's people producing nothing who the year before were producing something. If there were more demand, they'd produce something.

Now if you look around the world, you can find lots of examples of countries with lower unemployment rates than the United States that are nonetheless poorer than the United States. How does that happen? That happens because when you're not in a downturn, the only way for a country to improve its living standards is to actually get better at producing stuff. When almost everyone who wants a job has one, the only way to get richer is for people to start being more productive. Productive capacity matters—a lot. But when lots of people who want jobs aren't doing hobs, you've got a different problem. A failure to mobilize the productive people you already have. In the scheme of things, that's a good problem to have since it's much easier to solve. But it's also a much more frustrating problem to solve precisely because there's no good reason it should be lingering like this.

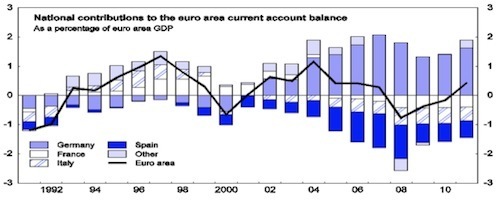

Evolution of Eurozone Trade Balance

I'm back in America, but still thinking about Europe. The OECD has a new survey out of the Euro area economy, including some slides (slides) from Pier-Carlo Padoan:

Among other things, you see here another illustration of the point that there's something very simplistic about the "Germany has high net exports because we make good cars" theory of global trade flows. BMW made good cars in the 1990s, too, but Germany ran modest trade deficits at that point. And if Germans (and Dutch, Austrian, Swedish, etc.) households started buying more consumer goods (or, equivalently, taking more vacations) the growth outlook for neighboring countries would be better. But this wouldn't just be a favor to the people of Spain, Germans would actually have more stuff. The Schröder government undertook a lot of politically difficult reforms in order to boost German productive capacity. But presumably the point of this was to actually reap more rapid increases in living standards and not just to try to win some kind of global exports championship.

Somewhat relatedly, I wonder what the economic cost of Germany's rather draconian Sunday store closure laws is? I have a sneaking suspicion that this is actually dramatically worse policy than people realize.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers