Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2467

December 17, 2010

Target The Forecast

From Adam Posen's talk (PDF) on monetary policy in the UK:

What British households have suffered in this regard [i.e., in terms of inflation] over the last year, however, is a decline in their purchasing power due to one-time factors that is neither amenable to reversal through monetary policy nor going to feed a more general rise in prices and wages. The MPC would only make things worse by making policy looking in the rear-view mirror, trying to make up for past mistakes, especially given the fact that the underlying trend inflation rate is below target.

His point is that the price level rose thanks to a VAT hike and a currency devaluation, rather than to an overheating of the British economy's productive resources. The logic seems compelling to me, but what's worth pointing out is that the point about rear-view mirror policymaking seems compelling as a general matter and not just in terms of this particular case. One of the slogans I've picked up lately from economics blogs is the idea that monetary policymakers ought to "target the forecast," i.e. explicitly stop paying attention to past performance and instead look at market measures of inflation expectations.

This should help keep things nicely contained and stabilized. If you explicitly say your objective is to keep market expectations of long-run inflation at around two percent (or whatever) then two good things come from this. One is that if expectations deviate from your target, investors are going to say to themselves "at the next meeting, these guys will act to bring expectations back in line with the target, so we should buy/sell before then." That on its own will bring expectations back in line with the target, allowing you to spend your meeting issuing self-congratulatory statements about your own credibility without actually doing anything. The other is that this eliminates the current ambiguous status of the central bank's self-published macroeconomic forecasts. Right now, when the Fed says growth is going to be such-and-such next year, that's supposed to be a prediction, but it kind of seems like a self-fulfilling prophesy. Either that, or the Fed is for some reason forgetting to take the Fed into account when writing its own forecasts.

Mitt Romney and Olive Garden

As a fan of David Frum, and of Mitt Romney, and of Olive Garden analogies, I'm primed to endorse this defense of Romney's flip-flopping:

I sometimes imagine that Romney approaches politics in the same spirit that the CEO of Darden Restaurants approaches cuisine. Darden owns Olive Garden, Longhorn steakhouses, and Red Lobster among other chains. Now suppose that Darden's data show a decline in demand for mid-priced steak restaurants and a rising response to Italian family dining. Suppose they convert some of their Longhorn outlets to Olive Gardens. Is that "flip-flopping"? Or is that giving people what they want for their money?

Likewise, the "pro-choice" concept met public demand so long as Romney Inc. was a Boston-based senatorship and governorship-seeking enterprise. But now Romney Inc. is expanding to a national brand, with important new growth opportunities in Iowa and South Carolina. A new concept is accordingly required to serve these new markets. Again: this is not flip-flopping. It is customer service.

Ezra Klein points out some problems with this line of thought. But I think the real issue here has to do with character. The executives of Darden Restaurants are basically trying to make money. And so are the owners of the firm. And that's fine. Most of us aren't so distressed by the idea that the firm is, on some level, a soulless money-making machine. But on this view, Romney is . . . what? A soulless power-seeking machine?

To a large extent our political system is already biased toward promoting power-crazed sociopaths into positions of authority. The public's aversion to people who appear to have this quality to a greater extent than other high-profile politicians seems very understandable to me. Meanwhile, at the end of the day Ross Douthat is right to say that this still leaves you necessarily puzzled by the question of what a Romney Administration would actually do. Is it so crazy for political activists and pundits to be curious about this?

The Latvian Catastrophe

Klaus Regling, chief executive of the European Financial Stability Facility, wants you to know that monetary union without fiscal integration is workable after all and he offers, as an example, Latvia:

Latvia which has a currency pegged to the euro, testifies to the success of this policy. Contrary to commentators who predicted disaster for Latvia early last year unless it gave up its hard peg – in line with advice from the commission – it did not devalue its exchange rate. A real effective devaluation was achieved through severe cuts in nominal income. Today its economy is growing again. Those outside "experts", who always seem to know what is good for Europe, should take note.

So to be clear about this, the Latvian economy suffered a 4.2 percent contraction in 2008. By way of comparison, in the horrible year of 2009 the US economy contracted 2.44 percent. So that was a very bad recession, much worse than the American recession. At this point, so called "outside 'experts'" predicted disaster for Latvia in early 2009 unless it devalued its exchange rate. Latvia declined to devalue and its GDP shrunk 18 percent! That's the disaster right there. Overall GDP growth for 2010 is forecast to be slightly negative again. So, yes, Latvia has returned the growth. But the toll was terrifyingly high.

As ever, there were some "real" shocks involved in this. Some loss in Latvian living standards was inevitable and unavoidable. But the unemployment rate in Latvia is nearly 20 percent. That means a great many able-bodied adults are simply not working, not producing any goods and services for market consumption. That represents a vast loss of living standards that could have been largely avoided in a floating exchange rate regime.

To suggest that this is some kind of success story that illustrates the underlying workability of the system is horrifying.

Freak Yourself Out About North Korea Day

As I've said before, the relevant leaders in the Republic of Korea, Japan, and the USA deserve some credit and recognition for the fact that over the past 4-5 years the very dicey situation with North Korea and a not-so-cooperative China has been managed without anything disastrous happening. But even as Bill Richardson, New Mexico governor and sporadic DPRK envoy, arrived in Pyongyang to try to calm things down, there are new spouts of conflict. And the really sobering thing about the North Korea situation is that even relatively optimistic scenarios that have the conflict successfully managed without war until the Kim Regime implodes aren't all that optimistic.

And if you want to darken your thoughts on this matter even more, I'd highly recommend reading Colonel David Maxwell's brief paper (PDF) on "Irregular Warfare on the Korean Peninsula" for the Small Wars Journal. I would reconstruct Maxwell's argument by saying that people normally think of the possibility of DPRK collapse primarily through a Central European frame. You're implicitly assuming something like the collapse of the German Democratic Republic and its reintegration into the Federal Republic of Germany. And then from that starting point you're observing that it'll be much more problematic than even that problematic undertaking was.

Maxwell looks instead through more of an Iraq/Afghanistan lens. Why assume, he asks, that incoming foreign soldiers will be greeted as liberators? Because the Kim regime was nasty? Well, the Taliban's nasty too. Saddam was nasty. What if a significant proportion of the population is hostile to incoming outsiders, and what if remnants of the DPRK security apparatus actively resist the new order? He notes that this is especially plausible since the official DPRK ideology is heavily oriented around (often mythical) feats of irregular resistance to Japanese occupation in World War II.

Beyond being alarming, Maxwell argues that we need better and broader planning for these collapse scenarios. That seems wise and all (planning is good), but part of the difficulty is that the political management of the situation would get much, much worse if there were high profile planning sessions about DPRK collapse. What's more, the government of China seems unlikely to be interested in participating in any such planning, and yet some kind of political coordination with Beijing is crucial.

Tax and Spend

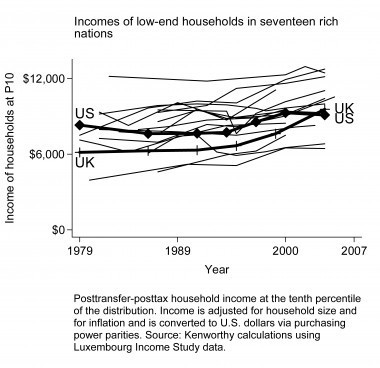

I'm a tax enthusiast, in part thanks to the work of Lane Kenworthy. But taxes are unpopular. So unpopular, in fact, that a combination of political opportunism and psychic revulsion from advocating for tax hikes leads progressives to spend a lot of time dreaming up ways to achieve beloved ends that don't involve tax hikes. But so here's a good Kenworthy post about how whatever happens with inequality, you help the poor by raising taxes and handing money over to poor people:

In some countries with little or no rise in income inequality, such as Sweden, government transfers increased and so did the incomes of poor households. In others, such as Germany, transfers and the incomes of low-end households did not increase.

Among nations with sharp increases in top-heavy inequality, we observe a similar disjunction. Here the U.S. and the U.K. offer an especially revealing contrast. The top 1%'s income share soared in both countries, and through the mid-1990s poor households made little progress, as the following chart shows. But over the next decade low-end American households advanced only slightly, whereas their British counterparts experienced sizable gains. The New Labour governments under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown increased benefits and/or reduced taxes for low earners, single parents, and pensioners. As Jane Waldfogel documents in her book Britain's War on Poverty, these were big policy shifts, even if not always high-profile ones. They produced a significant rise in the real disposable incomes of poor households.

Now insofar as skyrocketing Anglo-American income inequality is a symptom of a dysfunctional financial sector, healing finance should boost growth over the long haul and make lots of people better off. But lots of inequality (i.e., superstars like JK Rowling and LeBron James leveraging global communications technology to get super-rich) has nothing to do with finance and also little to do with the fate of the poor. What's relevant is that you need to have the gumption to take money away from people whose consumption has a low marginal value, and give it to people whose consumption has a high marginal value. And you want to try to do it in a way that doesn't strangle growth. The Nordic countries are living out there on the frontiers of political thinking, and manage to tax almost 50% of GDP on a sustainable basis. But it's all too rare that I see American progressives explicitly calling for a Nordic-style tax code.

Lucky for you, as a Christmas gift to the audience I'll be unveiling my thoughts on ideal taxation over the holiday season.

December 16, 2010

Endgame

We all living the good life:

— Foust on Boot on Afghanistan.

— Posen on UK monetary policy.

— Motivated reasoning among economics students.

— Lydia DePillis on the Height Act and Stephen Smith on the same.

— Richard Koo: "western nations have learned nothing from Japan's lessons and are likely to repeat its mistakes."

Kanye West, "Christmas in Harlem".

Bundestag Debate on Eurozone

Quentin Peel has an excellent report in the FT on a recent Bundestag debate that shows the shifting sands inside the German political elite:

German unwillingness to bolster the size of the €440bn eurozone stabilisation fund, or contemplate the issue of jointly-guaranteed eurozone bonds, was in danger of turning the European Central Bank into a "bad bank", said Frank-Walter Steinmeier, parliamentary leader of the Social Democratic party, and former vice-chancellor.

Jürgen Trittin, co-leader of the Green party in the German Bundestag, said the chancellor was regarded throughout the eurozone as a "Teutonic savings-monster" whose actions had aggravated the crisis. He accused her of "disorientation", and being driven by fear of the popular press. [...]

[Steinmeier] spelt out his three-point programme, outlined in an opinion article for the Financial Times on Wednesday, calling for a debt-restructuring for Greece, Ireland and Portugal, combined with a debt guarantee for the rest of the eurozone, and increased funds for the EFSF. He also backed the idea of issuing eurozone bonds in the medium term, combined with much closer political and fiscal co-ordination amongst the member states.

The price of integrating Europe in an unbalanced way that ran so far ahead of public consciousness has been criminally high. But I do think we see here that the basic calculation that forging ahead with a single currency would drive deeper integration is happening. Leaving aside the policy ideas here, what you're seeing is a European policy debate. It's not Germany versus some other country. And it's not a simplistic "Europhiles versus Europhobes" debate either. It's a real disagreement about the best way for Europe to proceed, like how Democrats and Republicans argue in Ohio about national policy.

Taxing Estates

I think if I read another snatch of writing where a progressive puzzles over why the estate tax is unpopular, I'm going to shoot myself. More informative, I think, would be self-examination. Why are liberals eager to tax estates. My own effort to think this problem over has actually made me less eager.

The estate tax is basically a wealth tax with a highly progressive rate structure. But instead of taking a tiny share of very wealthy households' wealth on an annual basis, it takes 0% of a given household's wealth on the vast majority of years and then a healthy chunk during whatever year the head of the household happens to die. There's no particular economic reason to structure a wealth tax this way. It was done, I assume, for some pragmatic reason of implementation and enforcement or else because it was "estate tax" was more politically sellable than "wealth tax." So that's fine, but it's not like the merits of this policy are some kind of holy writ handed down on tablets.

Now that's not to say the case for estate tax cuts is strong. A debt-financed temporary estate tax cut is lousy stimulus. A fully offset temporary estate tax cut would almost certainly reduce aggregate demand. And a debt-financed permanent estate tax cut doesn't boost long-term growth by boosting savings and investment—100 percent of the revenue loss is offset by increased bargaining. This is all just transferring wealth to rich people. So the case for a lower estate tax would have to be the case that nobody is making—permanent estate tax reduction fully offset by some kind of tax hike or spending cut. And you'd have to evaluate any such proposal on the merits depending on what it is.

Taxes and Mandates

Orrin Hatch on the constitutionality of the individual mandate:

The constitutional question is whether any of these enumerated powers authorize Congress to require that individuals purchase health insurance or pay a fine. The only potential candidates are the power to tax and the power to regulate interstate commerce. Last year, to get the legislation passed, liberals denied that the fine is a tax and made sure that the law calls it a "penalty" and exempts those failing to pay it from the punishment that applies to tax evaders. But today, to defend the legislation in court, the Obama administration argues that the penalty is a tax after all. Judge Hudson called this disingenuous argument "a transparent afterthought" and no court has agreed with it; some have declined to address it at all.

It seems to me that Hatch has inadvertently undone himself here. He says that liberals denied that the fine is a tax. And he says this was done in order to get the legislation passed. Well if they were denying, who was doing the accusing? Conservatives, it turns out. The Wall Street Journal editorialized against the stealth tax increase, Cato's Michael Cannon explained that "Health-Care Mandates Are a Middle-Class Tax," Greg Mankiw discussed the implicit marginal taxes involved.

Now looking at the Obama administration's legal strategy he's successfully identified some hypocrisy. Raising taxes is unpopular, so conservatives accused the mandate of being a de facto tax increase. Liberals pushed back against this criticism to pass the law. But now that it's passed, they're admitting that basically the fine is the same as a tax. He's got Obama nailed! But what's the legal force of this supposed to be? Political rhetoric isn't unconstitutional. The point is that the government's taxation powers give congress the authority to force people to pay money contingent on various kinds of behavior. If you want to buy gasoline, you need to pay the federal gas tax. If you want to not buy health insurance, you need to pay a fine. Either way, the behavior-linked collection of money is designed to (a) raise revenue and (b) assist in the regulation of the national economy.

The Revolving Door

I agree with Ezra Klein that sometimes people get too upset about the "revolving door" phenomenon, but in this post I think he misstates the main objection to it:

My hunch is that this is fundamentally because of money. If the public thought that expertise was the actual good being provided, they wouldn't mind very much. But the trail of cash suggests that the real trade is that firms and groups give money to former players, and then those former players give money to their former colleagues, and what the firms and groups end up getting isn't an explanation of how the committee process works, but some giveaway that they bought at the expense of the public. Put differently, the market isn't for people who can navigate the government. It's for people who know how to bribe it.

As I understand it, the concern is that the the job itself is a bribe. In a super-crass version of this, Firm A says to Regulator Z "you won't be in this job forever, but if you make a lot of decisions favorable to Firm A then we'll hire you after you quit." In a more realistic version what happens is that Regulator Z observes that many of his predecessors have gone on to lucrative careers in Industry A and that they probably couldn't have had if they'd pissed off all the Industry A CEOs. This biases his decision-making in a problematic way.

Sometimes I think this problem is more apparent than real. Any conceivable set of decisions that the FCC makes is going to be favorable to some set of large corporations. So being in the pocket of "big business" as such isn't a big problem. But sometimes the problem is very real. The entire financial reform debate, for example, has featured a lot of ideas that put the interests of the financial sector as such at stake. Many observers, including Ezra Klein, have posited that shrinking the size of the financial sector overall should be a goal of reform. Obviously, though, people with an ambition to go get jobs in the financial sector are unlikely to espouse such goals.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers