Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2466

December 18, 2010

The Wage Decline

Alan Blinder is excellent:

When it comes to wages, the basic story of recent decades is redolent of Scrooge. Real average hourly earnings (excluding fringe benefits) now stand roughly at 1974 levels. Yes, that's right, no real increase in over 35 years. That is an astounding, dismaying and profoundly ahistorical development. The American story for two centuries was one of real wages advancing more or less in line with productivity. But not lately. Since 1978, productivity in the nonfarm business sector is up 86%, but real compensation per hour (which includes fringe benefits) is up just 37%. Does that seem fair?

Not to me. But I think that progressive discussions of this phenomenon wind up overcomplicating things when contemplating the causes. Over the past 30 years the Federal Reserve has proven itself to be much better at preventing inflationary episodes than at preventing recessions. There's no long-term tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. A perfect central bank should be able to produce full employment and price stability all the time. But no real central bank is perfect. And what the Fed has done for 30 years is err on the side of letting aggregate demand get too low. Sluggish median compensation growth is a straightforward consequence of this decision.

Nice Regulator, Mean Regulator

I of course endorse Natalie Avery's case for making the liquor license approval process more collaborative and less adversarial. There are some cases where adversarial regulation is really appropriate. Something like Spencer Bachus' view "that Washington and the regulators are there to serve the banks" is totally inappropriate for that sector.

But local government should want to see businesses grow and prosper. Where the need for regulation arises, the goal should be help firms comply with the regulations not be super-adversarial about it.

In general, I think we don't spend enough time thinking about when the "nice regulator" model is appropriate and when the "mean regulator" is what you want. But I think the main question to ask yourself is "would deliberately violating this rule on a consistent basis be a smart business strategy?" Think about restaurant kitchen sanitation. All else being equal, if you own a restaurant it's in your interest not to make your customers sick. Thanks to information asymmetries, I don't think we can trust this entirely to the market. Regulatory inspections are a fine idea. But we don't need to worry about restauranteurs willfully trying to run unsanitary kitchens. The regulatory agency here should be a "nice regulatory" model that tries to help businesses understand what they need to do to get up to code.

Banking's not like that. It makes a ton of sense for bankers to invest lots of time and energy in deliberately locating and exploiting loopholes and the like. Here you need a "mean regulator" who's suspicious of the motives of regulated entities and always on the lookout for problems.

Money and Metaphysics

Paul Krugman and Kevin Drum recently wrote about the problematic definition of "money" in the modern world.

I think this issue can be helpfully illuminating by dusting off one's BA in philosophy and attempting a little metaphysical analysis that will help clarify what the actual issue is here. What is money? Well money is currency. And it's easy to say what the currency of the United States of America is: dollars. So what's a dollar? Well the word is ambiguous. But a dollar is a unit of account—you can give the price of things that aren't dollars in terms of dollars. And a dollar is also a medium of exchange. One dollar, is a perfectly safe perfect liquid asset with a value of $1. Four quarters are a perfect safe investment in dollars. Four quarters are worth one dollar by definition so they can never lose value in dollar terms. And they're perfectly liquid: as long as you're in the USA, anyone will accept four quarters in exchange for goods or services valued at $1.

The problem of the "broader aggregates" is that there are lots of things that have properties closely resembling those of dollars. My checking account with PNC Bank is basically perfectly safe (thanks to the FDIC) and it's almost as liquid as quarters. The vast majority of stores will accept my debit card and there are ATM machines all over the place where I can exchange electronic checking account commitments for physical dollars. Something to note here is that some forms of physical currency actually fall as short or shorter of ideal-type money than checking accounts. A sack containing 10,000 Sacagawea dollars is, in most situations, a less liquid asset than an ATM/debit card linked to a bank account worth $10,000.

But circumstances can change rapidly. I remember a few years ago I was in New York during a giant blackout. That caused everyone's ATM cards to be suddenly, albeit temporarily, useless. 999 days out of 1,000 the guy with the sack of Sacagawea coins is a moron, but when the power goes out he's everyone's best friend. The impact of this massive monetary shock on the city's economy becomes difficult to evaluate since obviously the general lack of electricity was a substantial shock that caused all kinds of asset price fluctuations (perishable food plummets, batteries and flashlights skyrocket) and rendered many capital goods useless. But it's interesting to try to think about.

What if there was no blackout, but for some reason all ATM/debit cards in the Denver area didn't work for a week. Posit that the nature of the problem was well-understood and everyone is perfectly confident that their accounts will work again in seven days. So it's not a banking panic, it's just that suddenly these assets turn temporarily illiquid. The answer is you'd have a giant, albeit temporary, collapse in real output. Households would immediately pare back spending in order to conserve cash. Business relationships that are embedded in continuing social relationships would continue on a credit basis, but nobody would make any large purchases from strangers. Mass layoffs would be avoided only because the duration of the monetary crunch was known to be temporary and no boss would want to act like a giant asshole about the problem. Having the Army fly helicopters over the Denver area and literally drop dollars on the city would in fact boost growth.

So to return to where we started, the real issue Krugman is pointing to is not difficulty in defining money, it's difficulty in quantifying the money supply. That's primarily because the money-ness of different things can change over time. If money-ness were a constant property of assets, then you could say "a checking account is 99% money-like, so we'll say a $10,000 checking account constitutes $9,900 worth of money supply." The blackout, however, doesn't eliminate the checking out instead it makes it (temporarily) much less money-like. And it's challenging to quantify in real time how money-like different things are. We can say qualitatively that the "shadow banking" panic started to render large classes of assets less money-like. Letting money market funds go bust, as some retroactive bailout opponents think we should have done, would have had the same impact. So do radical revisions in estimates of the safety of short-term Italian debt.

December 17, 2010

Endgame

Your promises and lies:

— The books and bathtubs economy.

— The excellent Harriet Tregoning will stay in place running DC's planning department; Cathy Lanier's still in as police chief as well.

— After demanding extra time for START amendments, GOP Senators didn't offer any amendments.

— IMF doesn't want people to vote Labour in Ireland.

— Redskins sign Donovan McNabb to a big contract extension and then bench him in favor of Rex Grossman.

Pitchfork's glowing review of the Pretty Hate Machine re-issue led me to revisit the album. It's good! This is "Terrible Lie".

The Symbolic Power of Nuclear Deterrents

I once made a French diplomat really angry by suggesting that the persistence of the modest-sized British and French nuclear arsenals sent a really bad message about nuclear proliferation to regional powers all around the world. This interesting WikiLeaked cable from London about British thinking on the Trident and the French reaction to it offers some evidence in this regard.

Charli Carpenter explains:

The French reaction is very interesting indeed; the French appear to have understood a decision to reduce or eliminate the UK's nuclear force as a danger to France's own nuclear capabilities. Presumably, the threat would come from activists and political actors within France, who would leverage British de-nuclearization in arguments against the maintenance of France's own deterrent.

This suggests that France and the UK, even prior to their recent defense agreement, understood their nuclear deterrents to be symbiotic rather than competitive, even in a symbolic sense. The British and French nuclear arsenals have never threatened each other in anything other than a symbolic sense; the sole possession of nuclear weapons could conceivably suggest military and political leadership of Europe. I had long believed that the persistence of the French nuclear arsenal was the most important reason that Britain would not de-nuclearize, but I had assumed that this was because giving up Britain's nukes might be perceived as a concession of French military and political predominance. What I didn't expect was that the French would put direct (if discreet) diplomatic pressure on the United Kingdom out of fear that they might lose the rationale for their own arsenal.

This suggests that British nuclear disarmament might indeed send a powerful diplomatic message. Of course, France and the UK are the most similar of the nuclear powers, and it would be a reach to suggest that India, China, etc. would feel the same pressure to disarm as France. Nevertheless, that the French take the symbolic power of the message so seriously is very interesting indeed.

I would say that the issue here isn't so much the Indias and Chinas of the world as the Brazils and South Africas. Whether public opinion in non-nuclear third world democracies is more inclined to believe "responsible liberal democracies are moving toward disarmament" or else "important countries each need an independent nuclear deterrent" is relevant to the long-run trajectory of policies in these countries. And the posture of the British and French governments is a big boost to option number two, in a way that's bad for the world.

If You Don't Build It, The Price for All the Other Stuff With Increase

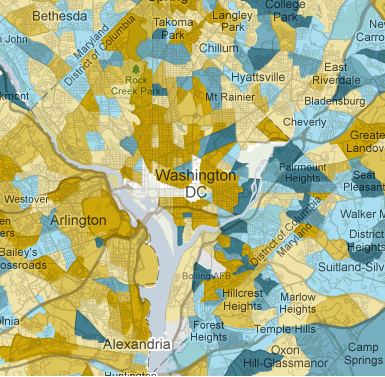

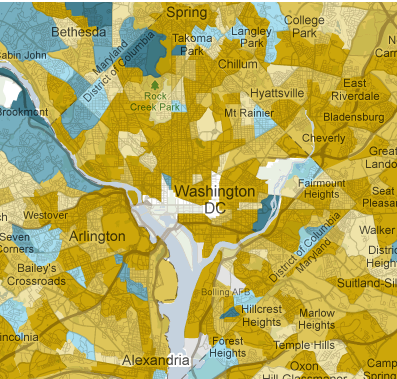

Lydia DePillis used the NYT's ACS Explorer tool to contrast the rise in DC median incomes with the sharper rise in median rents. Here's income:

Pretty good. And here's rent:

Much stronger and more consistent.

And this right here is the social cost of restrictions on construction. In a world where the cost of housing is primarily determined by construction costs, then rising incomes should lead to housing costs falling as a share of income. But that's not what's been happening in DC or other successful American cities. Instead, the price of housing is being determined in large part by the implicit price of regulatory permission to build. That means rents rise as a share of income, and wealth is transferred to incumbent homeowners. This is a regressive transfer that also happens to be bad for the environment and bad for overall economic growth.

What's the Point of Medicare Privatization?

David Brooks wants to privatize Medicare:

But it should be possible to strengthen the safety net while modernizing some of the Great Society structures. Paul Ryan, a Republican, and Alice Rivlin, a Democrat, have come up with a Medicare reform plan in which new enrollees would receive a fixed contribution from the government, growing a bit faster than inflation. They would apply that money against the cost of health insurance. This would make Medicare a defined contribution program and save hundreds of billions. If Obama said he was open to thinking about this sort of fundamental reform, he'd generate tremendous excitement on the right.

I think this is a dubious use of the term "save." If I went to CVS, bought a box of Diet Cokes, and kept them in the fridge in the CAP kitchen I'd save a substantial amount of money relative to my current practice of constantly going to the soda machine. That is to say, I'd have the same amount of Diet Coke but I'd be spending less money. Alternatively, I could reduce expenditures by not buying as much Diet Coke.

What Ryan-Rivlin does is buy less Diet Coke. It sets a hard cap on Medicare expenditures, thus reducing government outlays. Then in an unrelated move, it dismantles the publicly administered single risk pool of Medicare and replaces it with multiple privately administered for-profit risk pools. The combination of these two moves is a sleight of hand designed to make you think that the structural shift is "saving money" when in fact it does nothing of the sort. Creating multiple privately administered risk pools doesn't offer any efficiency gains. It simply creates an adverse selection problem and ensures that the rationing decisions made necessary by the hard cap will be made by employees of for-profit firms rather than government employees. It also makes the political economy of restraining Medicare spending worse, since in addition to senior citizens and health care providers you'll add insurance companies as a new constituency ready to demand that Medicare account for an ever-larger share of national output.

As best I can tell, the privatization idea is in here essentially as an ideological tic. The conservative establishment in America is very hostile to "spending" and "entitlements" but the reality is that conservatives don't actually want to cut Medicare. They don't want senior citizens' health care rationed and they don't want health care providers' incomes to decline. So there's an enormous market for concepts that will paper this dissonance over. But the fact of the matter is that Medicare is extremely efficient at transforming tax revenues into purchases of health care services; if you want to spend less money, you need to buy fewer services. There's almost no administrative efficiencies to be found.

The Mysteries of the Global Supply Chain

If you look at the back of an iPhone it says "Designed by Apple in California, Assembled in China." The actual parts out of which it was assembled come from a whole bunch of different countries. Consequently, the actual value is dispersed to a whole bunch of places. But as Jacob Goldstein expalins, under current statistical rules "the entire manufacturing cost of each iPhone — about $179 for each iPhone 3G, as of 2009 — is counted toward China's export totals" even though the China-located assembly process only accounts for about $6.50 per phone.

As Yuqing Xing and Neel Detert explain (PDF) in "How iPhone Widens the US Trade Deficits with PRC" the result is that what's really a very successful American export product (the iPhone's intellectual propert and industrial design characteristics are much more valuable than its manufactured components) ends up counting as a net import.

That's a little primer in why it's worth keeping in mind that objects in the balance of trade may not be exactly as they appear. Still fundamentally it strikes me as underscoring the fact that it's a problem for the world when a major economy doesn't let its currency float. There are a lot of different ways these trade statistics could be assembled, and a lot of different ways you can interpret them. What's not open to interpretation is the fact that in an open exchange rate regime, currencies adjust in line with trade flows. When Americans start buying more stuff from Canada, that makes Canadian money more expensive; when Canadians buy more American stuff, the reverse happens. This is all nice and automatic, and doesn't depend on any particular interpretation of the global supply chain. It's a good system, and China and the world would benefit from moving in that direction.

Private Mass Transit In a Congestion-Priced Future

I'm not nearly the private mass transit booster that Stephen Smith is, but his discussion of the possibility brings to my mind the fact that this is part of what's missing from a lot of congestion-pricing conversations. I often hear it said that to make congestion pricing work, you'd need to pair it with massive new investment in mass transit. And I don't think that's right at all.

If you take a snapshot of gridlock in any American city, part of what's striking about it is that the vast majority of vehicles on the road are going to be operating at well below their capacity. Mostly you're looking at individuals driving alone in cars that could comfortably seat two or four people. And many of the vehicles on the road can comfortably carry many more people than that. So if you look at Atlanta or Phoenix, it's not like the existing capital stock of vehicles is inadequate to the task of carrying everyone to work in a more efficient manner. What's lacking, instead, is the incentive. If you carpool, you cause yourself some delay and inconvenience and only save a little money on gas. With a good congestion pricing plan, suddenly everyone faces less delay and less inconvenience, but now carpooling entails substantial savings.

But—and here's my real point—the basic economic logic of congestion pricing would make private bus service much more viable. Right now, buses usually only work with hefty public subsidies. That's because every person who rides the bus to work is, in effect, doing a favor to everyone who drives by freeing up space on the road. But the actual allocation of the subsidy is highly politicized and only loosely related to actual demand. In a world where you have to pay for the space you take up on the road, but also pay lower taxes, then it's much easier to imagine private bus service taking off. That, in turn, would mean a much more rational pattern of bus-related investment. Meanwhile, funds that are currently expended on generalized bus subsidies could instead be used to specifically enhance poor people's disposable income.

And, yes, I'm well-aware that none of this is going to happen any time soon. But I think people are oftentimes insufficiently utopian in their thinking about public policy. Think about how different policy was in 1960 compared to today.

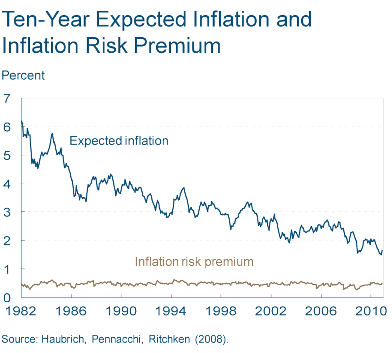

Disinflation Forever!

On the subject of targeting the forecast, via Mark Thoma the Cleveland Fed has a nice chart of the evolution of inflation expectations over time:

This looks to me like expected inflation was undesirably high in the first half of the 1980s, so the monetary authorities took steps to bring it down. And then they just . . . kept on taking steps to bring inflation expectations down. Why do this? Was there some big problem in 1997 that we had to solve? Or 2002? The trend here is subtle enough that you can miss it, but implicitly American monetary policy seems to be consistently disinflationary without specifically articulating this goal or offering a reason for it.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers