Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2462

December 28, 2010

Film Subsidies

Ryan Kearney reports on the questionable practice of offering tax incentives for movies to film in particular locations:

But if you live in D.C. proper, as I do, you might stop laughing when you learn that your District stewards gave $1.4 million in taxpayer dollars to How Do You Know, which filmed in Adams Morgan last year. That's about one percent of the film's budget — a pittance for Columbia Pictures, which produced the movie, but a significant sum to District agencies facing major budget cuts. D.C.'s film office would argue that the money was necessary to ensure that How Do You Know filmed here. Opponents would argue that the screenplay was set in D.C. — Wilson plays a Nats reliever, Rudd an executive facing securities fraud — so where else would they shoot?

I think that's actually a fairly weak objection. Bones is set in Washington, DC but the producers manage to put it together with very few authentic DC location shots. This aggravates me to an extent, but doesn't imperil the success of the show in any serious way.

The real question here is why would you think a target tax subsidy for the movie industry is a smart economic development strategy. Let's say you start with a certain quantity of public services and a balanced budget. Your money's coming in from property tax, sales tax, income tax, and a few licensing fees. Now it's definitely true that a tax break for folks who film movies in your city might spur some additional business activity in your city. But you'll have to pay for it with either higher taxes or else fewer services. Won't the higher tax rates just offset the positive impact of the targeted tax break? And if you're willing to live with fewer services in exchange for lower taxes, wouldn't it be more beneficially to cut rates across the board?

Chris Christie Likes One Class of Public Employee: Himself

As we've seen before, one category of lavish spending on public employees that Christ Christie likes is lavish spending on himself, as when he was a US Attorney he repeatedly came in over-budget for his travel expenses without proper justification. Similarly, Steve Benen's been noting that Christie and his Lieutenant Governor decided to take simultaneous vacations, leaving the state in the hands of an Acting Governor during the snow emergency gripping the state.

It's not the biggest deal in the world, but I do think it's telling in a small way. After all, the whole point of having a Lieutenant Governor is that this kind of thing won't happen. Imposing a "no simultaneous vacations" rule would be inconvenient—folks like to travel on Christmas—but failure to impose such a rule vitiates the public function of the offices. You'd think a governor so eager to be filmed dressing-down sundry public employees for living high on the taxpayer's money would be more sensitive to these problems, but he seems to have a giant blind spot when it comes to his own conduct.

Mysteries of Preemptive Fiscal Adjustment

Felix Salmon writes about the Japanese budget situation and observes that "The lesson here, I think, is that it's very, very hard for a government to enact a serious fiscal adjustment unless and until the bond market forces its hand."

Well, I agree. But I'm less depressed about the whole thing than Salmon is. I mean, really, why would it be the case that governments enact serious fiscal adjustments when the bond markets aren't forcing their hand? What I actually find remarkable is the quantity of media and political whining that goes on about the fact that countries don't do this. Normally, though, we expect human beings and the organizations they run to respond to incentives. If people cease wanting to buy Japanese debt, then the Japanese government will find ways to issue less debt. But demand for Japanese debt is high, so why wouldn't the government keep issuing more?

That's not to say these endless debts are optimal policy for Japan. What they ought to be doing is trying to have more economic growth. Finance their government with a bit less debt and a bit more printing of yen. That'll create elevated inflation expectations and spur growth. More immigrants wouldn't hurt either. I think the real mystery is why unconstrained governments are so reluctant to really put the pedal to the metal.

Frontiers of Regulatory Arbitrage

A "private" company, roughly speaking, is one that's not traded on a stock exchange. And yet people might want to trade shares in such firms. So it seems folks have been setting up various kinds of exchanges and vehicles where you can do just that. Peter Lattman reports on the beginnings of an SEC inquiry into the trading in some of the hottest private stocks:

It is uncertain what exactly the S.E.C. is looking into, but several securities lawyers say it could relate to understanding the number of shareholders at these companies.

That would be relevant to regulators because Facebook and other start-ups have a reason to keep the number of shareholders to under 499. If they had 500 shareholders, S.E.C. rules would require them to disclose their financial results to the public.

The pooled vehicles being set up to acquire Facebook stock, for instance, could push the company's shareholder count above 499 if the S.E.C. counted the number of investors in the funds.

I have no opinion about the underlying issue here, but I think this illustrates several points about financial regulation. One is that regulatory arbitrage is pretty easy. Even a seemingly straightforward rule about how you can't have 500 or more shareholders turns out to have a loophole big enough to drive a truck through. But you also see that stopping regulatory arbitrage isn't some kind of impossible task. Neither the SEC nor the financial press is really in the dark about what's happening here and there may be a crackdown. This is also one of the reasons that regulatory discretion, much bemoaned during the Dodd-Frank debate, is sometimes a very good thing. Pretty much any hard-and-fast rule about this that you could write will have some kind of loophole in it. Only an agency with some discretion at its disposal will be able to enforce the spirit of the 500 shareholder rule.

Cycles of Car Ownership

The news that grocery delivery service FreshDirect is looking at raising funds to expand into DC and Baltimore is a nice indirect illustration of why I'm so obsessed with things like parking regulations.

The issue here is that which services are available in an urban neighborhood is in part a function of what everyone else is doing. If lots of households in Neighborhood X don't want to drive to the grocery store (either because they don't own a car or else because near-store parking is expensive), then a relatively low-cost grocery service for Neighborhood X is a viable business due to the high volume. And of course conversely, if Neighborhood X has a low-cost, high-volume grocery delivery service then at the margin households are less likely to want a car.

Parking regulations tend to tip this in the other direction. If new apartment buildings all need to provide more parking spaces than market conditions would support, then more residents will be car owners than would otherwise be the case. That will mean less pedestrian-oriented retail and fewer market opportunities for delivery-oriented businesses. That, in turn, makes car ownership much more objectively desirable than would otherwise be the case. The resulting level of car ownership and driving is perfectly authentic—people aren't suffering from false consciousness—and can thus present itself to people as the "voluntary" result of "preferences" and "culture." But in reality, it's in part the result of regulations. The regulations increased car ownership at the margin, which altered the economics of the neighborhood in a way that made car ownership more valuable.

During the 25 years after World War II, the United States employed regulations of this sort as part of an industrial policy oriented around automobile manufacturing, steel, highway construction, and homebuilding. But as a development strategy, I think cars/steel/asphalt/houses has more-or-less run its course. And as environmental policy, it stinks. An alternate strategy based on deregulation of land use, taxation of pollution, and investment in density-facilitating infrastructure would spur further technical and organizational innovations in the service sector to help meet the patterns of demand suggested by intensive land use and lower rates of car ownership.

Alfred Kahn

RIP:

Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where he spent most of his career, said on its Web site that he died from cancer.

As chairman of the Civil Aeronautics Board under President Jimmy Carter, Kahn was probably the first Washington regulator to put himself out of a job. He argued that airlines could serve consumers and business best by competing with each other, a novel notion at a time when prices and routes were government-controlled.

If you want to know why air travel is so sucky, it's largely because Kahn was correct. It turns out that in a competitive market, what consumers really wanted was affordable air travel. Under the old paradigm, airlines were providing service quality that was too good and too expensive. This is a bummer for those of us who mostly travel for work—when someone else is paying you want the high price, high quality equilibrium—but it's a small victory for efficient allocation of scarce resources and a great boon for domestic tourism and far-flung families trying to stay in touch.

December 27, 2010

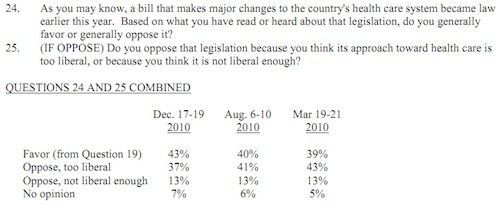

The Median Voter Supports The Affordable Care Act

We've seen this before, but today CNN has another poll (PDF) confirming that the Affordable Care Act's conservative critics are a minority:

I'm not 100 percent sure if "not liberal enough" is the way I would describe the law. But you make the ACA better by making it more aggressive. That's a public option, but it's also more forceful implementation of the Independent Medicare Advisory Panel concept and a more aggressive phase-out of the tax subsidy for employer-provided health insurance.

The Coherence of Conventional Ideological Categories

I liked Chris Beam's NY Mag article on libertarians, but I want to quibble with this:

Yet libertarianism is more internally consistent than the Democratic or Republican platforms. There's no inherent reason that free-marketers and social conservatives should be allied under the Republican umbrella, except that it makes for a powerful coalition.

People, especially people who are libertarians, say this all the time. But we should consider the possibility that the market in political ideas works is that there's a reason you typically find conservative and progressive political coalitions aligned in this particular way. And if you look at American history, you see that in 1964 when we had a libertarian presidential candidate the main constituency for his views turned out to be white supremacists in the deep south. Libertarian principles, as Rand Paul had occasion to remind us during the 2010 midterm campaign, prohibit the Civil Rights Act as an infringement on the liberty of racist business proprietors. Similarly, libertarians and social conservatives are united in opposition to an Employment Non-Discrimination Act for gays and lesbians and to measures like the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act that seek to curb discrimination against women.

And this is generally how politics goes in most countries. You have a dominant socio-cultural group allied with the bulk of the business community, and you have a more diffuse "left" coalition of reformers associated with labor unions and minority groups. There's nothing "inconsistent" about organizing politics this way.

Top Ten New (To Me, At Least) Culinary Experiences of 2010

Mmm…tasty. Aiming for diverse recommendations here reflective of the places I've been in the past year:

— Sichuan Pavilion in Rockville, Maryland. Probably too far out of the way to be worth your trouble if you're just visiting, but go here if you live in DC.

— Roast Fish Legend in Beijing. I'm having some trouble verifying on the Internet that this place exists, but I have a photo and you may have a friend who can help you decipher the Chinese characters. It's delicious. Get the roast fish (obviously); the black bean sauce is particularly good.

— Kushi in DC. Very close to downtown, very close to the Convention Center, definitely come if you're visiting the city. It's a very unusual, very good Japanese dining experience. If you love sushi, you'll of course want some sushi, which is excellent but similar to other excellent sushi; the real winner here is to explore the other options.

— Brunch at Casa Oaxaca, in Oaxaca. You can of course find a much better value for your money if you avoid doing anything this obvious, but the fact of the matter is that this was great brunch.

— No-name comedors in Oaxaca. Basically the reverse of the above. Point yourself away from the Zocalo and walk until you find yourself outside the city center and stop in for a bite or two at some places that have customers and smell good.

— The Lab Gastropub is mostly just convenient if you happen to be doing something at USC, but they served french fries with some kind of pumpkin dipping sauce that was fantastic and has proven hard to replicate.

— Xiabu in some shopping mall in Dalian, China. This is apparently a chain. They do hot pot. The people working there didn't speak any English, but after a lot of furious gesturing Ezra Klein and I were able to persuade them to bring us 100 RMB worth of food, about 80% of which was delicious.

— Go to ethnic restaurants in Berlin and tell them "I'm not German". Your (German) dining companions will be offended, but the results speak for themselves.

— If you're ever in Ramallah, don't miss the Palestinian-Italian fusion cuisine (think noodles or risotto with Middle Eastern flavors) at Orjuwan.

— Last but by no means least, El El Frijoles in Sargentville, Maine.

Enjoy.

The Economics of Ripoffs

Something that immediately presents itself when you're a tourist, especially in a poorer country and especially when you're a tourist in a common tourist destination like Oaxaca, is the prevalence of scams and ripoffs. You're always on guard for scams, you're also aware that a certain amount of getting scammed is inevitable, and since the overall price level is low and the scam-runners are likely poor you perhaps don't care too much if you get ripped off some.

But this all strikes me as an underexplored element of economic interactions. The great genius of capitalism is facilitating mutually beneficial exchanges. I want a can of Diet Coke more than I want 8 pesos, so I hand 8 pesos over to a shopkeeper and he hands me a can of Diet Coke. Win-win. Then there's fraud where you outright lie about what's happening. That we understand, and it's generally illegal.

But there's this whole other world where, to a greater or a lesser extent, one party to the transaction is getting ripped off. We know this stuff happens. People buy lottery tickets, people put tokens into slot machines, and people pay fortune tellers. You can model all this behavior as self-interested and mutually beneficial by simply asserting that the people buying tickets are obtaining some large quantity of subjective utility from the lottery, but I think examining lottery marketing tends to cut against this interpretation. And this can move up from the realm of pure gambling. I saw a TV ad the other day marketing life insurance to AARP members. The idea of life insurance is that average payouts are less than average premiums (hence profit), but this bad investment may still be a good idea for your family because the economic impact of the loss of a breadwinner will be so devastating. But the whole logic of life insurance completely fails to apply to retired people.

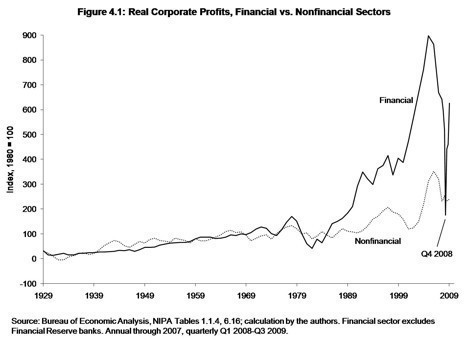

I thought of this all recently in terms of continuing discussions of the mysterious sky-high profitability of the financial sector.

We often have this conceit that ripoffs are an economically marginal phenomenon that applies to, sure, tourists and gambling addicts and maybe naive poor people going to see tarot card readers. But if you look at the price premium people are willing to pay for "organic"-labeled products and the dubious science behind the theory that these products are superior to conventional varieties, I think it's clear that yuppies aren't immune to getting ripped off, either. And I think we should be open to the possibility that this is happening in finance. How much do the sundry pension fund beneficiaries, 401(k) holders, endowed nonprofit managers, etc. of the world really know about the investment game? Are they really that much more savvy and sophisticated than their working class lottery ticket buying peers? Or does their self-image as savvy sophisticates make them that much more prone to being ripped off? After all, Bernie Madoff was able to swindle a bunch of very sophisticated investors out of a great deal of money. He did it through actual, prosecutable, criminal fraud. But not every scam and ripoff is a fraud, and not everything that's legal is a mutually beneficial transaction.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers