Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2460

December 30, 2010

Cracking Down on Drug Tourism

Relatively few Americans are aware that recent years have seen a large backlash in the Netherlands against the quasi-legalization of marijuana that their country is famous for. In particular, the "legalization in one country" paradigm has helped generate a lot of drug tourism that Dutch people don't seem to like very much. But Keith Humphreys reports that the drug tourism issue may not doom the coffee shops after all:

An EU judge has upheld the legality of Maastricht's proposal to restrict "coffee shop" sales to Dutch citizens. This decision probably saves the coffee shops as a social experiment in the long term despite the fact that the loss of tourist business will make some of them fold. Maastricht and a number of other cities were planning to close their shops rather than continue to experience the problems that come with drug tourism.

Good news for Dutch people. Of course this won't fly in the USA. If Michigan wants to create legal smoke shops, they'd need to put up with a stream of people from other states coming in to get high. Of course you might see that as a feature—something to draw business in from out-of-town the way Vegas did with gambling back in the day.

Constitutional Utopia

The field of constitutional law has always featured a great deal of what's known as "motivated belief" where people look at the document and tend to see it as supporting their preexisting policy conclusions. Ezra Klein had a great post on this yesterday. Since the 111th Congress saw Democratic control of the House of Representatives, Democratic control of the Senate, and Democratic control of the White House paired with an overwhelming Republican preponderance in the federal judiciary we saw in particular a huge upsurge in conservative belief that the constitution prohibits Obama/Pelosi/Reid policies.

One thing worth saying about this, is that I think a lot of this kind of constitutional thinking constitutes a form of pernicious dreaming about the post-political utopia. Like what if the constitution really did entrench conservative policy preferences? What would happen then? We're imagining that the structure of mass and public opinion are the same, and so is the structure of interest group politics. But suddenly most of the stuff progressives want to do is unconstitutional. What happens next? Do progressives all go home and just give up? That doesn't seem realistic. Do progressives stage a violent revolution, arguing that it makes no sense to let the dead hand of the 18th century block social justice in the 21st? That doesn't seem desirable.

The most likely outcome, and the most sensible one, is for progressives to just do what conservatives do—try to win elections and appoint judges who interpret the constitution in a way that's friendly to progressive policy aims.

Ebooks and Page Numbers

I love ebooks. I loved my kindle when I first got it, and now I love my kindle ap for ipad. But I share John Holbo's grievance:

But I'm thinking about quoting our John in something I'm writing (yes, on Zizek). But I can't footnote a Kindle edition. No pages. What will the world come to? Bibliography has gotten a bit old and odd in the head in the age of the internet, but the existence of pages themselves is kind of a watershed. On the one hand, there's really no reason why a text that can be poured into a virtual vessel as easily as it can be inspirited into the corpse of a tree should have to have 'pages'. Still, it's traditional. Harumph. I suppose I'm going to have to use Amazon's 'search inside' or Google Books and pretend I read the paper version, as a proper scholar would. Or just email John Q. and ask.

What's particularly aggravating about this is that it seems so unnecessary. The technical challenge here would be trivial, and the gains in terms of getting a bigger purchase on the educational market would be large.

Labor Markets, Immigration, and Inequality

Here's Mickey Kaus' proposed solution to inequality:

If you're worried about incomes at the bottom, though, one solution leaps out at you. It's a solution that worked, at least in the late 1990s under Bill Clinton, when wages at the low end of the income ladder rose fairly dramatically. The solution is tight labor markets. Get employers bidding for scarce workers and you'll see incomes rise across the board without the need for government aid programs or tax redistribution. A major enemy of tight labor markets at the bottom is also fairly clear: unchecked immigration by undocumented low-skilled workers. It's hard for a day laborer to command $18 an hour in the market if there are illegals hanging out on the corner willing to work for $7. Even experts who claim illlegal immigration is good for Americans overall admit that it's not good for Americans at the bottom. In other words, it's not good for income equality.

I agree with Will Wilkinson that the . If we banned all health and nutrition assistance to the poor, this would cause poor people to start dying off and the gini coefficient would show a reduction in inequality. Or as Wilkinson says, "nation-level income inequality would drop if the government herded all the poor people onto boats and dropped them off on a distant island."

But what about Kaus' example here of the great late-nineties immigration crackdown pioneered by Bill Clinton. Do you remember that? I don't remember that. I don't remember it because it didn't happen. Deportations reached a record high just this year, not in the late nineties. What happened in the nineties was that a tight labor market led to a spike in immigration.

Curtailing population growth might lead to rising real wages in an agricultural society or a small country with an economy based on fossil fuel exports, but that's not how the American economy works. If you want to tweak the distributive implications of US immigration policy the economically and ethically sensible thing to do is to increase legal immigration of high-skill people. The tightness or lack thereof of the labor market is mostly a consequence of monetary and fiscal policy, with more rapid growth of the labor force making it feasible to have more growth without risking inflation.

The DeJuan Blair Factor

I'm continually blown away by the fact that DeJuan Blair slipped into the second round of the NBA draft. This particularly egregious because it's not like he was a seventeen year-old playing in an obscure foreign league. He had two college seasons under his belt, and based on his play there his success in the NBA was very predictable. But he slipped because he stands at the intersection of two frequent errors in NBA drafting.

One is an irrational aversion to "undersized" big men. NBA teams correctly note that college success does not directly correlate with NBA success, so beyond raw numbers they look for physical tools that are likely to lead to success. This is reasonable as far as it goes, but different things project better or worse and rebounding in the NBA actually correlates pretty highly with rebounding in college. It's also true that size helps with rebounding, but the point is that if an undersized player has success at rebounding in college, he's likely to continue doing so in the pros.

The other issue is injury aversion. Kevin Pelton covered this issue in an article I linked to yesterday, but the problem here is that GMs seem to vastly overrate the value of your average draft pick. There are 30 players picked in the first round of the NBA draft and 30 more picked in the second round. There's only 30 teams, and in practice most teams play an 8 or 9 man rotation even though rosters are bigger than that. That means that even in the first round there's a very high ratio of draft picks to rotation spots. And of course some rotation players are actually pretty bad. On top of that, lots of times you draft a good player (LeBron James, Shaquille O'Neal, etc.) and then they leave in free agency. The upshot is that if you get a good year or two or three out of someone before their career is ruined by injury then you're coming out ahead.

Now of course it matters if you're talking about the number one overall pick or something. But teams drafting in the second half of the first round have absolutely no business worrying about injuries. What you should be worried about is whether or not the guy you get will be any good at all.

December 29, 2010

Endgame

Just like before:

— The Founders were no libertarians.

— Teams should worry less about injuries in the NBA draft.

— Immigration reform would bolster the housing market.

— Paul Krugman, neoliberal.

— Do incoming House Republicans understand that even if they ban lame duck sessions, future congresses can un-ban them?

Amerie's "1 Thing" didn't really succeed in launching Go-Go into the mainstream but I like it anyway.

Top Five Neglected Features of the Affordable Care Act

Underrated law signed earlier this year contains a number of provisions that are only tangentially related to the core health insurance market reforms, each of which would have been considered important achievements had they passed as standalone measures:

— Reform of student loan process to eliminate rip-off by for-profit lenders.

— Community transformation grants to help make the built environment more conducive to public health.

— $12.5 billion in grants for community health centers.

— Nationwide calorie menu labeling regulations.

Incidentally, I'm glad to see that the "Affordable Care Act" lingo that I started trying to popularize months ago as an alternative to "ObamaCare" has been taken up by the administration.

The Conservative Recovery

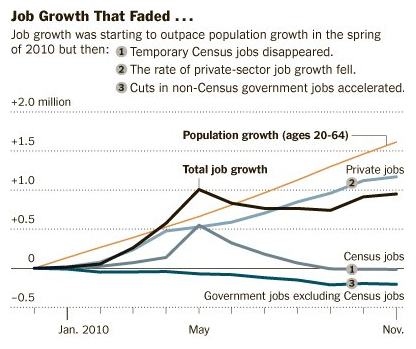

The state of the labor market is not good, which has understandably taken a toll on the popularity of Barack Obama. But what's underappreciated is the extent to which the bad labor market reflects what conservatives say they want to see. As David Leonhardt points out, we're basically seeing a structural decline in public sector employment:

Now I'm not saying people should be happy with the state of the economy. I'm saying, instead, that conservatives should wake up to the fact that their economy theory is nonsense. On their telling, the state of the economy is bleak due to Obama's socialistic policies and if we just trimmed back government the private sector would come roaring back. The truth is that under Obama the private sector has been growing and the public sector's been shrinking. But public sector shrinkage hasn't spurred private job growth, it's been a drag on it. Which is exactly how it should be. Your town's firefighters are also customers for your town's stores and plumbers. Cutbacks in bus service make it more difficult for people to get to work and participate in the economy. If we'd had more stimulus—specifically more fiscal aid to state and local government—then those public jobs wouldn't have gone away (lowering unemployment) and the income streams attached to them wouldn't have gone away either, spurring private employment and further improving the labor market.

Real Talk From Muriel Bowser on WalMart

With DC's mayor Adrian Fenty on the way out, I've been wondering if Muriel Bowser who took over his old City Council seat and has been a key ally of his on the council is someone I should be looking to for good ideas in the future. These remarks on WalMart reported by Lydia DePillis seem very sensible to me:

"I don't mean to offend anybody," she said, "but we already have enough beer and wine licenses. Where can somebody go buy clothes, right now?" The room was silent. "Where? Nowhere?"

"I get your concern," she continued, holding out her hands in an appeal. "But I need you to get my concern. I can't go to my community and say, this is all you deserve. I can't do that."

Bowser also pointed out that the community had brought Walmart upon itself by refusing densification at key spots along Georgia Avenue, ignoring recommendations from the Great Streets program.

That all seems about right to me. If you allow for dense development, the tendency is to make suburban-style big box stores a not-so-optimal use of space. If you insist on low-density, then you get big box stores. If you insist on neither high density nor big box stores, you get . . . noplace to buy clothing.

Monetary Policy Literature

Given that You Shall Know Our Velocity is not, in fact, about the velocity of money, Ezra Klein asks for recommendations of literary treatments of monetary issues.

I haven't actually kept up with his more recent work, but I think the earlier fiction of Neal Stephenson is intriguing in this regard. The key thematic elements are preoccupation with debt and hyperinflation in a way that I think is misguided in the present day but made sense in the early 1990s milieu. Interface, originally published under a pen name, is basically about the effort of a shadowy cabal to stage a coup aimed at preventing the US from defaulting on the national debt. Snow Crash gives the initial impression of a standard postapocalyptic "cyberpunk" scenario, but it swiftly becomes clear that there's been no war here. Instead the back story has to be an effort by the US government to cope with a deficit crisis by printing money. His "Great Simoleon Caper" short story offers an alternative path to currency anarchy in which encryption and the digitization of money lead to a breakdown of the tax system.

Anyways, this is reminding me that I really liked these books and should probably read Anathem or the Baroque Cycle.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers