Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2469

December 15, 2010

There Is No National Sock Shortage

This USA Today story about kids asking santa for basic necessities is actually more tragic than most people recognize:

Santa Claus and his elves are seeing more heartbreaking letters this year as children cite their parents' economic troubles in their wish lists. U.S. Postal Service workers who handle letters addressed to Santa at the North Pole say more letters ask for basics — coats, socks and shoes — rather than Barbie dolls, video games and computers.

Something important to note here is that this is not only sad, but fundamentally avoidable. The world is not suffering from a shortage of socks. If the government tried to give an iPad to everyone who writes in asking for one, we'd swiftly run out of iPads. The supply is constrained. But we have lots of socks. There's nothing stopping the government from buying socks and giving them to everyone. What about the money? Doesn't the money have to come from somewhere? Not really. As Ben Bernanke says "[t]he U.S. government has a technology, called a printing press (or today, its electronic equivalent), that allows it to produce as many U.S. dollars as it wishes at no cost."

Now of course having the Post Office initiate a big sock-purchasing program would be pretty goofy. But the point is that we have in this country right now lots of factories running below capacity. Lots of workers doing no work. Lots of trucks not delivering anything. We're not short on ability to produce more things, or on ability to transport, and distribute more things. We have citizens who would buy more things if they had more money. The real shortfall we're facing, in other words, is a shortage of money. This is a good kind of problem to have, since it's actually really easy to fix: Just print more. But it's also an extremely frustrating problem to have, since it's so easy to fix. The shortage of money isn't the only problem America has. We also have, for example, a shortage of really excellent teachers and it's hard to know what to do with that. But our money shortage is very solvable.

Higher Education From 50,000 Feet

Someone else needed Mr Canaday's money more.

He's talking about the United Kingdom, but John Quiggin's effort to engage the UK tuition debate by starting again from first principles, is relevant to the United States as well. That's because here, too, we have policy debates that pivot around a status quo that's radically inegalitarian in a way that tends to confuse discussion:

My starting point is that, in a modern society and economy, nearly everyone needs to finish high school and the great majority need further education (academic, professional/technical or vocational) beyond that, if they are to thrive and prosper. So, rather than thinking about universities as the destination of a select few, and then about various second-best alternatives for others, we should be starting from the view of post-secondary education as a universal service like school education or health services. That does not mean that everyone should get the same post-secondary education (any more than everyone should get the same health services), but it does mean a presumption that everyone should have access to educational resources of similar quality.

That's radically different from a system where historically-determined differences in endowments and funding drive massive inequality in resources which in turn produce and perpetuate inequality in outcomes. This inequality is most evident in the dominance of Oxford and Cambridge graduates among the elite, but it is replicated all the way down the higher education hierarchy.

The higher education funding landscape in the United States is very complicated due to the mix of "private" and "public" institutions, the large quantity of public funds that are appropriated to private institutions, the large quantity of private funds that are raised by public institutions, and the way the tax code provides a public subsidy for private donations. However, the same basic structural issue exists. The institutions that are most exclusionary in their admissions policies are the ones that have the most resources. And this inequity replicates itself throughout the hierarchy. Within any given state's state university system, the tendency is for the more exclusive institutions to have higher budgets. Community colleges are worse-funded than selective ones.

All this defies logic.

I can think of two broad principles that would be more defensible than funding by exclusivity. One would be funding by need. This would say that teenagers whose parents have modest incomes need resources more than do teenagers whose parents have high incomes. So institutions that attract a disproportionately high income client base should attract little support from the public. That means reduced direct appropriations, and at a minimum social pressure on civil society actors not to donate to highly privileged institutions. Another would be funding by quality. Here you would say that resources ought to flow to institutions with a proven track-record of producing unusually large student learning gains. In our current system, I think that funding quality is what we think we're doing. Yale is "better" than the University of Connecticut so funds flow to it. But in our current setup, better simply means more exclusive. It's a measure of the quality of the inputs, not the quality of the instruction. The result is that both the public sector and the civic sphere are essentially acting to redistribute wealth and opportunities upwards.

Stuck in the Middle With Rich Lowry

National Review editor Rich Lowry has an interesting column on income inequality with a strange ending:

At the moment, American politics offers two separate, distinct ways not to address these issues: Either the brain-dead populism of the Left that blames it all on trade and the decline of unions, or the brain-dead populism of the Right that extols the working class without taking serious note of its agony. We'll have to do better: There's a crisis in the middle.

That's a pretty broad middle ground there that includes, among others, Barack Obama and really the vast majority of mainstream liberals. It's interesting that Lowry's article contains no mention, for example, of taxes—hardly an obscure political issue. Redistributive taxation seems to me to suggest itself as the most straightforward attack on inequality, and if you want to do the redistribution specifically as wage subsidies so as to not undercut bourgeois virtue I have no problem with that.

Monetary Policy and Asset Prices

(cc photo by Jeff Kubina)

I was arguing yesterday that 25 years worth of wage stagnation, occasional recessions, and no episodes of inflation together constitute a powerful prima facie argument that monetary policy has been systematically too tight. That doesn't necessarily mean it's been dramatically too tight or anything. Maybe it's just that interest rates should have been 0.25 percentage points lower from 1985 onwards. That would still make a big difference over time.

Something some people said in response is that we may not have had CPI inflation, but loose money might drive asset price bubbles. People say this fairly frequently, but I don't understand how it's supposed to work. I've seen several efforts to debunk the loose money = bubbles hypothesis via empirical work (PDF, for example), but I also think it's very problematic as a theory. After all, what does it mean to say there's a "bubble" in the price of houses or the price of tech stocks? It means, I think, that current prices are based on overestimating the long-run demand for homes or for the goods sold by tech firms.

Clearly, things like that do happen from time to time. But how would higher interest rates avoid those occurrences? It's easy to see how tighter money could lead to lower asset prices via slower growth and reduced demand and expectations of demand. But that doesn't eliminate the "bubble," the mismatch between anticipated demand and actual demand, instead it lowers the price of the asset by actually lowering demand.

Bubbles, it seems to me, have to do with the fact that (a) making correct estimates is hard, (b) frailties of human psychology, (c) certain "the market can stay rational longer than you can stay liquid" asymmetries, and (d) to an extent bad regulatory incentives. Making money tighter or looser should alter the average price of assets but there's no reason to think it would change the basic social and psychological dynamics that sometimes lead to large-scale mis-pricing.

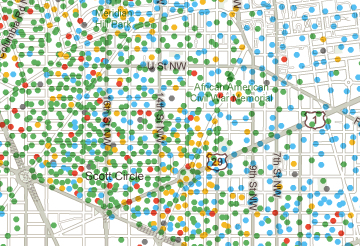

Census Tract Map

If I may say so, the New York Times' interactive explorer letting you see check out American Community Survey data for every neighborhood in America is awesome.

The first thing I looked at, personally, was the racial breakdown in the DC neighborhoods where I've been living for the past 7 years. I'm always hearing about what a divided, segregated city this is and that's never really been my personal experience. And, indeed, it turns out that Census Tracts 43 and 44 where I used to live are very mixed. Census Tract 47 where I live now measures as 84 percent African-American, but I think that data's probably out of date and the area's whiter than that now.

If you zoom out, though, you'll see that the conventional wisdom about a segregated city isn't false. Whites live on the west, blacks on the east, and there's a Hispanic cluster in the middle.

Ignorance is Bliss

Apparently for the Republican members of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the first rule of a shadow banking run is you do not talk about shadow banking:

The Republicans, led by the commission's vice chairman, former congressman and chair of the House Ways and Means Committee Bill Thomas, will likely focus their report on the explosive growth of subprime mortgages and the heavy role played by the federal government in pushing mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to purchase and insure them. They'll also likely focus on the Community Reinvestment Act, a 1977 law that encourages banks to lend to underserved communities, these people said. [...]

During a private commission meeting last week, all four Republicans voted in favor of banning the phrases "Wall Street" and "shadow banking" and the words "interconnection" and "deregulation" from the panel's final report, according to a person familiar with the matter and confirmed by Brooksley E. Born, one of the six commissioners who voted against the proposal.

A lot of this has been adequately debunked elsewhere, and I won't rehash it. But consider this. Suppose the housing bubble was 100 percent caused by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Community Reinvestment Act, and other government efforts to expand homeownership. What, exactly, is it that this theory would explain? Well, it would explain why housing came to be overbuilt. And it would explain layoffs in the construction sector. It would explain an elevated level of foreclosures and it would explain an unusually high rate of FDIC bank closures.

This is basically the story of 2007. Home prices fall, construction activity declines, unemployment rises, people start talking about whether there's a recession, blah, blah, blah. It's all somewhat interesting and somewhat important, but it doesn't even begin to explain how we got to where we were in the winter of 2008-2009 with unemployment heading up to 10 percent. And once unemployment's at 10 percent, you hardly need a theory of why a lot of people can't pay their mortgages. If you lose your job and can't get a new one, you're going to have trouble paying the bills. But how did we get the 10 percent unemployment? It's not like 10 percent of the country was previously engaged in building homes for poor folks getting rich on CRA loans.

There was a run. In the shadow banking sector. It came about as a result of regulatory changes. That run led to a huge increase in the demand for safe, liquid assets. For money, basically. And this in turn led to a huge decrease in the demand for goods and services.

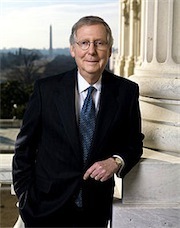

No Vote, No Pork

Here's a little Washington tradition that I don't really understand:

Earlier this year, McConnell asked for $4 million for marijuana eradication efforts by the Kentucky National Guard; $1 million for construction of the Kentucky Blood Center Building; and $650,000 for Advanced Genetic Technologies, a DNA research center at the University of Kentucky.

When reporters asked about his earmark requests Tuesday, McConnell said he was "actively working to defeat" the massive omnibus bill since the Senate never had a chance to take up individual appropriations bills.

"I think there are many Senate members who have provisions in it for their states who are also actively working to defeat it. This bill should not go forward," he said. "And regardless of whether members had some input in the bill much earlier in the year when the bills could have been moved to the floor bill by bill by bill, it is completely and totally inappropriate to wrap all of this up into a 2,000-page bill and try to pass it the week before Christmas."

Why don't Democratic leaders take this stuff out of the bill? Surely the point of legislative pork, if there is a point, is to build support for your legislation. If $650,000 for some friend of Mitch McConnell's who works at the University of Kentucky is the price of his support for a giant appropriations bill, then that's a reasonable price to pay. But if McConnell thinks that, all things considered, it's a bad piece of legislation that he won't support then there's no point. No vote, no pork. It's absurd for Senators to request and receive earmarks, then turn around and complain that they're voting against the resulting legislation because it spends to much.

Deficit-Talk

Atrios: "I really can't comprehend that with 9.6% unemployment politicians keep talking about the deficit as if it's the big problem."

Of course he's right. The deficit is a problem only in the sense that the short-term deficit is currently too small. But this is one reason I'm surprised so many liberals are being so stinty in their praise of the recent tax deal. We'd just all been spending 12 months arguing that contrary to the conventional wisdom, short-term deficits should be smaller. We also spent a lot of time observing that conservative deficit-talk is fraudulent and all they care about is tax cuts for the rich. Then the Obama administration, after a year of fruitless austerity gambits, finally called their bluff. "Fine, you can have your deficit-increasing tax cut extension, but give me some other deficit-increasing stuff that my economists say has a higher multiplier than your tax cuts for the rich." Now the deal is done, and for all the panels and commissions and all the money Pete Peterson's spent the parties are coming together to make the deficit bigger.

Which is as it should be. As Larry Summers explained in his farewell talk:

Even with all the fiscal measures of the last several years, total borrowing in the American economy has failed to grow for the last 2 years. That is the first two year period since the Second World War when total borrowing in the U.S. economy has not increased.

Let me be clear: Even with our deficits, the amount of extra debt is less than the amount of reduced borrowing in the private sector. Increased federal borrowing has offset, but only partially, deleveraging in the private sector.

The answer: More public borrowing. Which is what we're getting.

The tragedy here, as I've said before, is that Pete Peterson is a public-spirited man who's wound up wasting a great deal of money paying people to talk about the deficit. If instead he'd paid more attention to talking up the work of Peterson Institute of International Economics researcher Joseph Gagnon about the need for more monetary stimulus, then I bet today we'd already have lower deficits and lower unemployment.

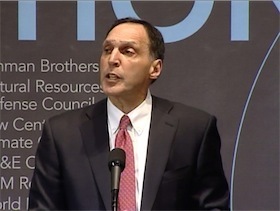

Doom and the Big Banks

Tyler Cowen has an interesting essay that's ostensibly about income inequality but in practice presents a very gloomy portrait of modern finance as both utterly dysfunctional and also irredeemably so. Ross Douthat responds by invoking a conservative version of the "break up the big banks" agenda whereby bank smashing is paired with balancing the budget.

I think this actually misses the full force of Cowen's saga of doom, which doesn't say that we won't restrain the financial sector because it's too politically powerful. It says we won't restrain the financial sector because we actually can't. For one starters, I think everyone should read Tim Fernholz on the myth of "too big to fail" where he persuasively argues that the basic logic of bailouts has very little to do with institution size. But I would also note that even though Cowen ends up dwelling on bailouts a bit in his piece, fundamentally the problem he highlights exists independently of bailout issues:

To understand how this strategy works, consider an example from sports betting. The NBA's Washington Wizards are a perennially hapless team that rarely gets beyond the first round of the playoffs, if they make the playoffs at all. This year the odds of the Wizards winning the NBA title will likely clock in at longer than a hundred to one. I could, as a gambling strategy, bet against the Wizards and other low-quality teams each year. Most years I would earn a decent profit, and it would feel like I was earning money for virtually nothing. The Los Angeles Lakers or Boston Celtics or some other quality team would win the title again and I would collect some surplus from my bets. For many years I would earn excess returns relative to the market as a whole.

Yet such bets are not wise over the long run. Every now and then a surprise team does win the title and in those years I would lose a huge amount of money. Even the Washington Wizards (under their previous name, the Capital Bullets) won the title in 1977–78 despite compiling a so-so 44–38 record during the regular season, by marching through the playoffs in spectacular fashion. So if you bet against unlikely events, most of the time you will look smart and have the money to validate the appearance. Periodically, however, you will look very bad. Does that kind of pattern sound familiar? It happens in finance, too. Betting against a big decline in home prices is analogous to betting against the Wizards. Every now and then such a bet will blow up in your face, though in most years that trading activity will generate above-average profits and big bonuses for the traders and CEOs.

It's true that the possibility of bailouts somewhat exacerbates this tendency. But it would exist even in a totally bailout free world. Richard Fuld and other Lehman Brothers honchos didn't get bailed out. But Fuld and other key Lehman executives still earned far more than most Americans during the good years, and even those who are still unemployed today are far richer than the average American. Looking back on the whole saga in retrospect, I'm sure they wish they'd gotten a bailout or somehow manipulated the situation a bit better. But if the alternative to getting rich and then going bust was to never get rich in the first place, then the alternative looks bad even without bailouts.

December 14, 2010

Endgame

Follow my lead:

— I'm amused by the quantity of "legal analysis" out there over the ACA case, as if the ultimate decision will come down to anything other than Justice Kennedy's personal preferences.

— Suburbs left behind as downtown office rents rise.

— Smart editorial on DC transportation policy.

— "The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited".

— Better web-metrics needed.

The Thermals "Never Listen to Me".

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers