Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2448

January 16, 2011

The Case For Federal Higher Education Policy

People are bound to debate at the margin what services should be publicly subsidized and to what extent. But voters like services and dislike taxes, so there's always a robust market for trying to fudge the idea that less subsidization means lower levels of service. One frequent dodge here is federalism, whereby you sort of wave around the idea of state government as a way to evade the issue at hand. To wit, via Kevin Carey comes the thinking of Rep Virginia Foxx of North Carolina:

Q. More generally, you have said you don't believe there's an appropriate role for the federal government in higher education. How far do you think the current, fairly significant role can — or should — be rolled back?

A. The federal government's involvement in higher education can and should be scaled back gradually in the coming years. Ideally we'd be able to reduce the burdensome federal bureaucracy and delegate much of the funding and policy decision making to state governments. This would help to foster better solutions to the specific issues confronting higher education and provide improved accountability for taxpayer dollars.

This is doubly nonsense. For one thing, as Carey argues if you devolved responsibility for research spending decisions to state governments then instead of "improved accountability" what you'd find is that each state government wants to fund research at home state universities. For an equal dollar amount of spending, we'd get less value.

More generally, I for one think labor mobility and social mobility are excellent things. If a poor kid from Detroit manages to get into the University of Michigan, graduate, and go get a good job in Chicago or New York or Atlanta or Houston then that's an American success story. And it's something officials responsible for education policy in Michigan shouldn't be afraid of—the long-term decline of automobile industry employment isn't something they're responsible for or able to change. But it's naturally that Michigan public officials will to an extent overweight the interests of Michigan qua Michigan relative to those of Michigan residents. If you tried to entirely devolve responsibility onto the states, then you'd find economically declining areas allocating a larger and larger share of a shrinking pool of resources to a kind of desperate effort to prevent people from leaving the area rather than giving them the skills that will best suit them in life.

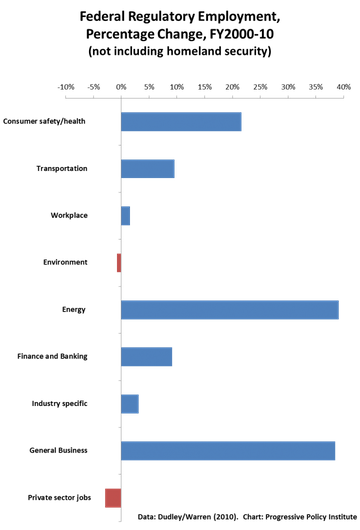

What We're Not Regulating

Apparently "Homeland Security accounts for roughly 90% of the increase in federal regulatory employment over the past ten years" and Michael Mandel shows that the increase in non-HS regulatory employment seems to have been quite uneven as well:

It's on the environment and in the banking sector where I think the case for more rigorous regulation was strongest ten years ago, yet those have not been the points of evidence. Admittedly, though, it's somewhat difficult to fully interpret this data without a better understanding of how the "energy" element relates to the environment.

Inaugural Galas

The last sentences of an article about South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley's inaugural gala:

Former Gov. Mark Sanford chose to forego a black tie gala for both his first election and re-election in favor of a low-key barbecue at the State Fairgrounds. Haley's event was paid for through private donations. Top sponsors included BlueCross BlueShield, Boeing, Duke Energy and SCANA.

This sort of arrangement actually looks to me a lot more like bribery than do conventional campaign finance shenanigans. If you assume a race between two perfectly sincere, utterly non-corrupt contenders it's still natural that private firms would want to spend funds helping the candidate they prefer to win the election. You don't need to be trying to influence anyone for it to be rational to spend the money. Paying for Haley's party is different. BlueCross BlueShield, Boeing, Duke Energy, and SCANA are really just providing a private benefit—a fun party—to Haley, her family, and her close political allies.

The Great Coincidence

Krugman: "It says something about the times we're in that Milton Friedman now looks left-of-center, at least on monetary issues."

Isn't part of what it says that it's a kind of odd and unfortunate coincidence that macroeconomic stabilization debates got tied up with other kinds of more conventional ideological ones? After all, if you assume Milton Friedman's argument for a negative income tax were being made in good faith the main difference between Friedman and a contemporary American liberal is that Friedman was strongly anti-paternalist. I think he's wrong about paternalism, but this plainly has nothing to do with monetary policy. It's like how on the one hand I don't like coconuts and on the other hand I don't like missile defense programs. I think a lot of progressives in America disagree amongst ourselves about how paternalistic the welfare state ought to be (and even though I don't agree with Friedman's take on this I agree that it should be less paternalistic than it currently is) so there's no real reason there shouldn't also be a range of views on monetary policy.

A Public Option for Banking

Chase says that unless it goes unregulated, the poor will suffer:

"We don't want to raise fees on our customers," a company spokesman said. "But unfortunately, regulation is forcing us to do it. And as a result, some customers may end up unbanked."

This statement is striking for a number of reasons, and the eye-popping earnings the bank announced on Friday don't exactly make the company more worthy of sympathy. So I've spent the last week trying to figure out why I was so sure I did not believe it the instant I read it.

Read on for why this is false (and see also Felix Salmon) but note as well that if you're concerned about poor people not having bank accounts there are a number of more straightforward ways to address this than knuckling under to Jamie Dimon.

After all, it's easy to understand why banks aren't super-interested in serving poor customers. The idea of getting bank deposits is to get a lot of deposits, and poor people by definition don't have much money so the rational executive is not super-focused on them. One cut at coping with this is to focus on those firms who do have existing retail relationships with poor people. When Wal-Mart has entered the check cashing business, poor people have benefitted and I think the decision to refuse Wal-Mart's effort to obtain a bank charter was a mistake.

But of course the most straightforward way to provide banking services to poor people is to just provide the service—create a public option for small-scale depository banking. Since postal services generally already have widespread retail operations, this is often done in collaboration with the post office and is known as "postal banking." But in an electronic age, you don't really need physical banks at all. Everyone could just be given an account with a $5,000 maximum on a Treasury Department computer and they could mail you an ATM card with your draft registration card when you turn 18. The accounts could pay 0 interest and wouldn't need to offer any services beyond basic "money goes in, money goes out" and nobody would have to be "unbanked." It would cost the government some money to administer such a system, but it would also amount to the government getting interest free loans from Treasury Bank customers so if people actually used it it would be a wash.

The Voldemort Effect

A coinage from Julian Sanchez:

In the Harry Potter books, the titular boy wizard is the subject of a mystical prophecy, destined to come into mortal conflict with the evil Lord Voldemort—and perhaps even capable of vanquishing him. But there's a wrinkle: One of Harry's classmates, Neville Longbottom, also fits most of the prophecy's description: born at the end of the seventh month, to parents who defied Voldemort three times. The prophecy adds, however, that "the Dark Lord will mark him as his equal"—which he does to Harry, in the failed attack that leaves the infant Harry with his iconic lightning-bolt scar. But that attack had only occurred because Voldemort, learning of the prophecy, had assumed it applied to the Potter boy, not little Neville. In other words, as Harry's sage mentor Dumbledore notes at one point, it was Voldemort's choice to regard Harry as his predestined foe that made it true.

There's a similar phenomenon in American politics, which I long ago mentally dubbed The Voldemort Effect. Maybe it's always been this way, but it seems like especially recently, if you ask a strong political partisan—conservatives in particular, in my experience—which political figures they like or admire, and why, they'll enthusiastically cite the ability to "drive the other side crazy."

I think the equivalence here is not only mistaken, but actually 180 degrees off base. You do see this Voldemort Effect in a lot of conservative thinking, but if liberals go awry it's more likely to be in the reverse way—a lot of Team Blue's thinking about politics is dominated by a kind of desperate search for leaders who won't drive the other side crazy. Hence Bill Clinton, southern good ol' boy. Hence John Kerry, decorated war hero. Hence calm, rational compromising Barack Obama instead of polarizing meanie Hillary Clinton. And that goes back to war hero George McGovern, southern good ol' boy Jimmy Carter, Massachusetts Miracle technocrat mastermind Michael Dukakis, etc. In retrospect all of these people are hated by the right and "obviously" represent just another strain of out of touch liberalism, but in advance each and every one appealed to the rank and file as somehow "different" from his predecessors in some key way.

The smug conceit here is that our answers are so self-evidently correct that the other side's failure to embrace them constitutes a kind of psychological disorder or a medical condition. Team Blue is medicine the country needs, but Red America's allergic. What we need is to find a figure with just the right mix of personal and cultural qualities, someone who won't activate the Red antibodies. The idea that the Republican Party voting base consists primarily of people whose interests would not in fact be served by the Democratic Party's agenda—that, indeed, in a loss-averse world it's conceptually quite difficult to frame an agenda that isn't contrary to the interests of some large group of people—seems totally off the table.

January 15, 2011

Quicksilver

I'm not sure it made a ton of sense to launch my "read more books" resolution by reading something as long as Quicksilver, but it certainly did turn out to have the extension treatment of monetary policy themes I was looking for.

As is often the case with the later work of successful "genre" writers, I thought this got a bit annoyingly self-indulgent at times, with Stephenson sometimes eager to show off some bit of 17th Century trivia (like that to "realize" your investment comes from the name of the Spanish currency, the real) in a distracting way. But at other times it's quite engaging and brilliant.

The message is that it's wrong to think of modern liberal capitalist democracy as a natural state of things from which bad deviations occur due to blundering or malfeasance. Rather, the world we know is a deliberate, contingent, human creation whose key elements had to be thought up by particular people for particular reasons. People think of things like telescopes as invented, but forget that banking and religious tolerance and nation-states are also inventions.

Doing It Differently

Ezra Klein observes that the Obama administration is mainly staffed with veterans of the Clinton administration since that's the only administration there are veterans of:

It's all a reminder, though, that party often matters a lot more than candidates do. Thinking back to the primary, Barack Obama was the guy who was going to transform Washington and chart an alternative to Clintonism and prioritize energy reform and wrest foreign policy away from the class of Democrats who had mucked it all up so badly. His was supposed to be a new, or at least somewhat different, Democratic Party than we'd seen in the '90s.

But then he got to Washington, sat down with the people who seemed to know what they were doing, and found that moving his agenda meant playing by the town's rules, that the people with the most relevant experience to the tasks he needed done were mostly Clinton veterans, that the voters weren't there for energy but were potentially there for health care, and that it made sense for him to put Hillary Clinton herself in the top foreign-policy slot. It's hard to imagine that Hillary Clinton or John Edwards would've done anything all that differently. For all the sound and fury of the primary, the state of the party and of the country told you a lot more about who would be in charge and what they'd be doing than did the rhetoric of the candidates.

I think there are giant, heaping important elements of truth in that. But there are also gaps. There are moments when an awful lot really does hinge on the president himself. Lots of important Democrats thought it made sense to push ahead with health care after Scott Brown's win. Lots of other important Democrats thought it made sense to surrender on health care after Scott Brown's win. Both "camp surrender" and "camp advance" included influential members of the Obama administration, both camps contained people who'd worked for Bill Clinton and people who hadn't worked for Bill Clinton, etc. But this was an important decision, not something sorted out on the staff level, so it turned out to be quite important that Barack Obama had an important job in the Obama administration. There's a substantial chance the call could have gone the other way with someone else in that office.

Look back on it, the main reason I ultimately agree that party matters a lot more than candidate attributes is because even though people matter a lot, it's hard to predict how they will matter. It turned out to matter, a lot, that in December 2009 Barack Obama was the kind of guy who wanted to gut it out and win ugly on health insurance reform. But I don't think if you asked me in March of 2008 to say what I thought distinguished Obama from Clinton and Edwards that "desire to gut it out and win ugly on health reform" would have been high on my list. And actually I don't think the candidates themselves are even in a good position to predict how they'll react to the vicissitudes of governing.

Jeff Sessions' Sleeping Bag Protectionism

Another one for the "ideological dissonance" files comes via Sallie James who observes that Jeff Sessions, one of the Senate's fiercest conservatives, is also a fierce defender of sleeping bag oriented industrial policy:

Under [the Generalized System of Preferences], Bangladeshi sleeping bags that competed with the Exxel Outdoors product were able to enter the U.S. duty-free. On behalf of Exxel Outdoors, Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-AL) last year refused to let any renewal of GSP pass that would not remove at least some sleeping bags from the scope of the GSP program (Inside U.S. Trade, Dec. 23).

With the future of the GSP program still uncertain, Kazazian said he is now expanding his Alabama plant in part to put pressure on Congress to either not renew the GSP program, or renew it in a modified form that would exclude imported sleeping bags from its scope.

That an Alabama Senator would be campaigning for higher sales taxes on Bangladeshi-made sleeping bags seems bizarre until you realize that they also make sleeping bags in Alabama. This kind of rent-seeking is unfortunate, but also pretty banal. But as I've been saying, what's so remarkably about Sessions' selective embrace of high taxes and big government is how dissonant it is with the contemporary conservative movement's insistence that the United States is facing some kind of ideological Götterdämmerung as the forces of freedom face off against Barack Obama's sharia socialism.

Construction Workers and the Recession

It's both true that the quantity housing construction has declined sharply and also that the unemployment rate has risen sharply, but as Scott Sumner points out for all that people want to keep talking about construction workers you just can't make the numbers add up on this:

January 2006 — housing starts = 2.303 million, unemployment = 4.7%

April 2008 — housing starts = 1.008 million, unemployment = 4.9%

October 2009 — housing starts = 527,000, unemployment = 10.1%

In a well-managed sectoral shock, what happens is a lot of construction workers lose their jobs and then . . . most of them get new jobs. But when you let aggregate demand collapse, that's not what happens and instead you end up with 10 percent unemployment. Instead of the construction workers getting new jobs, folks who sell things to construction workers lose their jobs and the cascade tumbles forward.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers