Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2444

January 20, 2011

The Trouble With Summits

This week's column for TAP argues that the precedent of high-profile US-China bilateral "summits" is a bad one:

Chinese President Hu Jintao's visit to Washington this week is being widely billed in the media as a "summit" with Barack Obama, and that fact may be more important — and more disturbing — than anything that transpires.

It's great that Hu is visiting, of course. But the precedent that such visits should be big-time summits in the style of U.S.-Soviet meetings in their heyday and that major issues should be primarily addressed in bilateral fora is a bad one. Embracing "the summit" may seem appealing in the short term, but Sino-American bilateralism is a poor strategy for a world in which China will all but inevitably amass an economy larger than the United States' in the near future. Our long-term interests are much better served by almost any conceivable decision-making process other than so-called G2 summits with China. The short-term frustrations of pursuing a policy of robust multilateralism should not distract attention from the urgent need to do the hard work.

The core issue, to be a bit flip, is that the United States of America has a posse.

Do People Know What Powers The President Has?

I've seen a lot made of the fact that Peter Baker's long article on Obama and the economy doesn't talk about housing, foreclosures, or HAMP. But that's not all it doesn't talk about! It doesn't talk about the Federal Reserve, and the President's powers to appoint its Chairman and Board of Governors.

But this crew—the Federal Reserve System in all its agencies—is the arm of the federal government that has primary responsibility for fighting recessions. The greatest power the president has to influence short-term economic performance is his ability to staff the Fed. Obama acted swiftly to reappoint Ben Bernanke as Chairman and acted very slowly to nominate anyone to serve on the Board of Governors. This has to be part of any discussion of the President's efforts to deal with the economy. Did nobody ever bring it to his attention that he should fill these vacancies?

Senate Democrats and Health Care Repeal

I think I agree with Kevin Drum that Senate Democrats shouldn't run from a health care repeal fight:

With Republicans in control of the House, it's not like the Senate can really get much done anyway. So what's the harm in wasting a bit of time and making this a knock-down-drag-out fight? After all, the House leadership got a nice, clean repeal vote by bringing up the bill under a closed rule and allowing no potentially embarrassing amendments and virtually no debate. In the Senate, by contrast, Democrats control things, and they can bring up all the amendments they want. So maybe they should play along, hold hearings, and force Republicans to vote on, say, an amendment to the repeal bill that would keep the preexisting condition ban in place. And another one that would keep the donut hole fix in place. Etc. etc.

That seems about right to me. You start with a "clean repeal" bill and then you start adding specific amendments exempting various popular and appealing aspects of repeal from the repeal. What better way to dramatize the reality that the specific elements of the bill aren't nearly as controversial as all the thundering against ObamaCare could lead you to believe.

Thursday Dental Emergency Blogger

So . . . I've spent all day at first the dentist's office and then with an oral surgeon getting a tooth ache diagnosed and then some "emergency" extractions. Consequently, I'm not feeling so great and you should expect some reduced output going forward.

What Does Apple Make?

John Cassidy on Apple versus Goldman Sachs is very interesting, but I think this part of the account is a mistake:

Unlike some corporations, Apple doesn't record on its balance sheet much of the value of its patents and other intellectual property—the look and feel of the iPad, for example. If it did this, the figure for total assets recorded on its books would be considerably higher, and its ROA would be lower. But accounting is only a small part of the story. (As far as I know, Goldman doesn't capitalize its intellectual capital, such as it is, either.)

The main reason why Apple is so much more profitable than Goldman is a reassuring one. It makes tangible things—iMacs, iPhones, iPads—that millions of people want to buy, and for which they are willing to pay a premium price. (I am writing this post on an iMac.) Despite operating in a highly competitive industry, Steve Jobs's firm has successfully differentiated its product line to such an extent that it now has considerable monopoly power: it can charge considerably more for its gizmos that they cost to manufacture.

Apple doesn't have "monopoly power" (its market share isn't even that big) in the markets for laptops or smart phones. What Apple has is intellectual property—operating systems. After all, Apple doesn't really manufacture "Apple" products. But even though Foxconn builds the iPhones, the bulk of the sale price ends up with Apple because Apple owns the intellectual property. You can see this by looking at the makers of Android devices, who get software free from Google but earn much smaller profit margins than Apple does. That's not because people don't like Android phones—people love them!—it's because the phone manufacturing business, as such, just isn't that profitable precisely because nobody has monopoly power in building phones.

By contrast, intellectual property is necessarily a kind of government-created monopoly. Thus anyone who owns intellectual property that people like is in good shape, hence big profit margins. And the other really profitable end of the business is the other monopolistic one, where cell phone operators own slices of a finite set of usable spectrum.

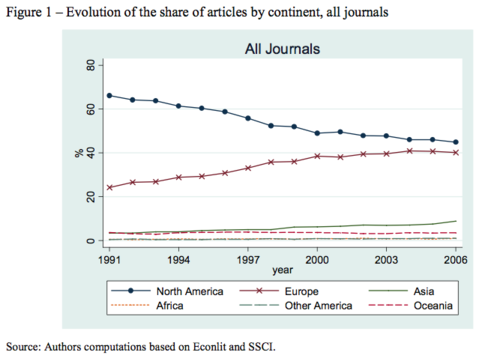

The Decline of American Economists

Frances Woolley offers us the latest sign of American relative decline:

This time, though, it's mostly the Europeans rather than the Asians who are catching us.

What Is Productivity?

A useful clarification from Karl Smith:

Countries aren't poor because the people don't have work, they are poor because the work they do is less "productive."

I put productive in quotes because I think even many readers of this blog instinctively equate productivity with the work ethic or can-do-it-ness of the worker. Productivity is mostly driven by machines and technology, however.

Having a lot of can-do spirit and a shovel is no match for being ho-hum and having a bulldozer.

Exactly. Chinese farm workers aren't lazy, they're working without machines which makes it difficult to be as productive as a guy using a tractor. I would add, though, that in the modern world productivity's about organization as well as machines. Federal Express didn't invent the airplane or the truck or the cardboard box, but they came up with a different way of putting it all together.

Against China Envy

Ryan Avent throws some much-needed cold water on the idea that China's recent economic growth shows that we ought to be emulating Chinese public policy. There's a lot to his argument, but I think this sarcastic aside actually captures the key point:

There is certainly a possibility that China has stumbled onto a striking new growth formula, and that Chinese citizens will ultimately grow every bit as wealthy as Americans and then some. That would be something! To move 1.3 billion people from grinding poverty to American income levels would represent a monumental step for human welfare. Who knows; it could happen.

There's often a tendency to get distracted by rates of change when levels are in many ways more relevant. China is a dynamo and Greece is a basket case, but Greece is much richer than China. Rapid Chinese progress does in part reflects the skill and wisdom of Chinese policymakers. But in large part it merely reflects the madness of a previous generation of Chinese policymakers—the people who left the country at such a low level in 1980 from which it's so rapidly been growing. If you look at the economic success of Chinese people in Taiwan or Hong Kong or Singapore or diaspora communities around the world, the striking thing about the PRC is how poor it still is.

The United States of America, meanwhile, is one of the richest countries on earth. A poor country can get richer by learning to do things that they already do in other countries. And a small country like Norway can get rich by managing natural resources well. But a large rich country like the United States actually needs to push the frontiers of the possible forward. Google and iPads aside, we haven't really done that over the past 10 years on the scale necessary to raise American living standards at a reasonable pace. That's a big problem, but there's not really any reason to think the Chinese have figured it out.

Farm Subsidies Benefit Landowners

(cc photo by luckywhitegirl)

Via Tad DeHaven, research from Barry K. Goodwin, Ashok K. Mishra, and François Ortalo-Magné tries to assess who derives the ultimate benefit from farm subsidies and discovers that much of it accrues to owners of agricultural land rather than farmers as such:

Farm subsidies make agricultural production more profitable by increasing and stabilizing farm prices and incomes. If these benefits are expected to persist, farm land values should capture the subsidy benefits. We use a large sample of individual farm land values to investigate the extent of this capitalization of benefits. Our results confirm that subsidies have a very significant impact on farm land values and thus suggest that landowners are the real benefactors of farm programs. As land is exchanged, new owners will pay prices that reflect these benefits, leaving the benefits of farm programs in the hands of former owners that may be exiting production. Approximately 45% of U.S. farmland is operated by someone other than the owner. We report evidence that owners benefit not only from capital gains but also from lease rates which incorporate a significant portion of agricultural payments even if the farm legislation mandates that benefits must be allocated to producers.

Highly regressive transfer, in other words.

What Would You Say To A Bunch of Heavily Armed Men Who'd Seized Control Of Your Village?

I saw the following photo, with caption, on the DOD multimedia website yesterday under the headline "Grateful Man." Their Flickr page has a different title:

A local Afghan man from Nawbor Village, Bala Murghab District, Baghdis Province, Afghanistan, talks through an interpreter (right) to (left) U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Nicholas Lewis, a scout with White Platoon, Bulldog Troop, 7th Squadron, 10th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, at Fort Carson, Colo., Jan. 16, 2011. The Afghan thanked the Afghan National Army and U.S. Army scouts for ridding his village of insurgents and bringing a better life to the Nawbor children, who gathered on the hill. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Kevin Wallace)

Now maybe the man is grateful and maybe the man isn't grateful, but don't you have to be pretty naïve to take this statement at face value? I mean, suppose this guy is an America-hating insurgent-lover, what's he going to say to a bunch of armed soldiers who took control of the village? If the Taliban ever seized control of my neighborhood and rolls around to ask what I think, I'm going to try damn hard to convince them that I'm on their side.

That's not meant as a knock on Staff Sargent Nicholas Lewis or Technical Sargent Kevin Wallace or anyone else involved. But the fact of the matter is that it's inherently difficult for a bunch of well-armed foreigners to obtain accurate information about what people think of the well-armed foreigner they're talking to at the moment.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers