Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2440

January 25, 2011

How To Turn Your Schedule III Blend Into Pure Hydrocodone In the Comfort of Your Own Home

An anonymous correspondent writes in with the following vicodin-related advice:

On the supposed addiction reducing potential of mixing acetaminophen into opioids, it's worth noting that any addict worth his/her salt can get around this in about 20 seconds. Hydrocodone dissolves in cold water. Acetaminophen doesn't. Crushing up a handful of pills, stirring into a glass of water, and drinking the water doesn't require meth lab levels of investment, planning, or thinking. It's useless and it's stupid.

Don't tell the DEA you heard it from me.

Frum's Infrastructure Bank

David Frum's proposed State of the Union speech contains both a lot to like and some to dislike, along with this wonky proposal:

I propose that all revenues from gasoline taxes, aviation fees, and other similar sources be placed in a fund directed by an independent infrastructure bank. The bank would be permitted to issue bonds up to a certain level, too. Instead of Congress writing a highway bill every five years, the bank would develop a list of priorities — no politics allowed. I'd suggest we have seven directors of the bank. Three would be nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Two would be nominated by a conference of the Republican state governors, two more by a conference of the Democratic state governors. The directors would serve fixed and overlapping terms. When we're balancing the budget, we can move slowly through the list of bank infrastructure priorities. In a year like 2011, when it's cheap to borrow and workers need jobs, we can bring projects forward faster. Congress would always have the last word, in an up-or-down vote. And Congress would decide whether to increase or reduce the flow of future tax revenues into the infrastructure bank.

Every American will have the reassurance that these new infrastructure projects are not pork barrel. They were not chosen to reach some political deal. The money you pay at the pump or at the airport or in future taxes on carbon dioxide and other pollutants will be reinvested toward faster travel, more advanced telecommunications, and cleaner water.

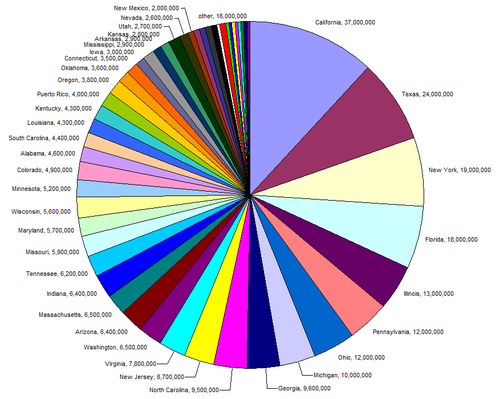

I like the spirit of this suggestion, but worry about the details. Slightly more than fifty percent of the American people live in California, Texas, New York, Florida, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, and Georgia and slightly less than 50 percent of the population lives in the other 41 states. Wouldn't the practical impact of board dominated by gubernatorial appointments be to even further exaggerate the American political system's over-weighting of the interests of low-population states? Crowded airports in New York, Dallas, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Miami, and Atlanta would be taxed to finance upgrades in Cheyenne and Albuquerque. Instead of a rail tunnel under the Hudson, we'd get a bridge to nowhere . . . exactly the problem this proposal was supposed to solve.

More generally, I'm skeptical of this kind of bipartisanship by fiat. If you think about an era of relatively unpolarized parties, mandatory bipartisanship in commission composition becomes an effective way of ensuring that patronage is doled out in an even-handed way. But in a polarized era, I think it mostly encourages tactical extremism in appointments—the most important qualification by far becomes the person's reliability as a partisan warrior.

January 24, 2011

Endgame

I can't sleep:

— Learning to love Katy Perry.

— Excerpts from the Harvard Magazine personal ads.

— Heaven forbid we allow a six floor building near a Metro station.

— Evan Bayh cashes is.

— The unbearable whiteness of anti-abortion punditry.

Katy Perry, "Teenage Dream"

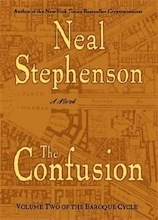

The Confusion

I didn't find The Confusion, Book Two of Neal Stephenson's Baroque Cycle, nearly as enjoyable as volume one. That's largely because the picaresque "Bonanza" sections of the novel don't seem to me to really add anything thematically to what we've previously seen of the adventures of Jack Shaftoe. I think this character simply isn't as fascinating as Stephenson thinks he is and it gets tedious at a certain point.

But the "Juncto" plotline dealing with the politics and economics of late 17th century Britain and Europe is great. Among other things, it contains an excellent narrative account of the seemingly mysterious fact that a shortage of money can lead to declining output of real goods and services. This is an idea people find highly counterintuitive for the very good reason that in your personal life you get more money by increasing your output of goods and services, so it seems clear that a national shortfall of money must be caused by insufficient production rather than vice versa. As Stephenson highlights, particularly at a time when people were walking around using little pieces of commodity metal as the medium of exchange this could easily become a very acute problem even in an otherwise advanced society. Given our current economic situation, for this reason alone I wish more people would read it.

Paleoliberalism

Here's a couple quotes from Yale historian Steve Pincus' 1688: The First Modern Revolution that I like:

Not only did the Whigs believe there had been a transformation of religious affairs, they also believed that the events of 1688-89 had ushered in a radical transformation of social policy. Robert Molesworth, who had been a strong supporter of the Whig ministry in the first decade of the century, clearly enunciated this position. Because defenders of the revolution believed, along with John Locke, that labor rather than land was the basis of all wealth, Molesworth argued that a government according to the revolutions principles would have a wide-ranging social agenda. "The supporting of public credit, promoting of all public buildings and highways, the making of all rivers navigable that are capable of it, employing the poor, suppressing idlers, restraining monopolies upon trade, maintaining the liberty of the press, the just paying and encouraging of all in the public service," all this and more Molesworth argued with the consequence of the revolution.

[...]

In the 1730s especially Opposition Whigs emphasized that the revolutionaries had adopted Lockean economic principles. They developed their economic policies on the assumption "that the lands of Great Britain are made valuable by the number of people employed in foreign and domestic trade, and in the woolen and other manufactures of this kingdom." The implication, based on "the authority of Mr. Locke," was a policy of progressive taxation. After the revolution, the regime, on Lockean principles, recommended "a Land Tax in preferences to any duties on commodities, whether imported or our own production." Others emphasized the postrevolutionary regime's assault on "exclusive trading companies." Still others pointed to the rage for social legislation, "salutory laws for the welfare of the public" that became possible only after the revolution.

The point is that there's nothing "classical" about contemporary libertarianism's hostility to progressive taxation, infrastructure spending, or social welfare expenditure. Nor is there anything "neo" about liberal support for free trade or suspicion that many real world examples of business regulation are aimed at restricting competition rather than serving the public interest.

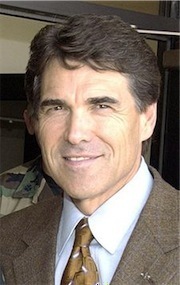

More Postcards From The Texas Miracle

Look who loves a good federal bailout:

Texas Gov. Rick Perry likes to tell Washington to stop meddling in state affairs. He vocally opposed the Obama administration's 2009 stimulus program to spur the economy and assist cash-strapped states. Perry also likes to trumpet that his state balanced its budget in 2009, while keeping billions in its rainy day fund. But he couldn't have done that without a lot of help from … guess where? Washington. Turns out Texas was the state that depended the most on those very stimulus funds to plug nearly 97% of its shortfall for fiscal 2010, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

This is one of the areas in which the political economy of the United States has had its most severe breakdown. Over the past year, conservatives have simultaneously complained about inadequate job growth and excessive public sector employment even though public sector employment has been declining and offsetting private sector job growth. At the same time, conservative state-level politicians who would have been in disastrous shape if not for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act have been running around the country pretending to believe that it's a huge burden on them.

If You Want Heavy Rail, You Need Density

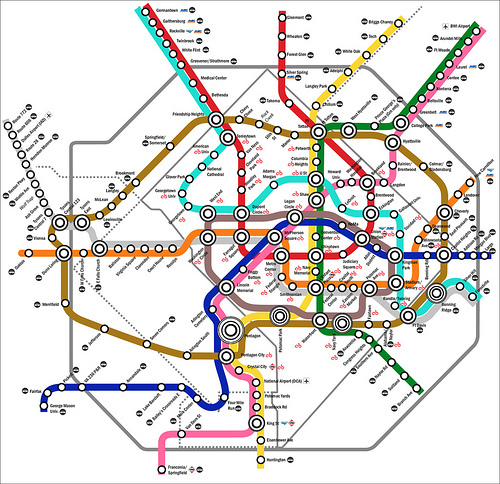

A Greater Greater Washington reader named thisisbossi dreamed up an impossibly ambitious scheme for expanding WMATA's heavy rail network:

Dave Alpert responded by saying the map brings to mind the actual heavy rail network of Paris, which "has more lines than even thisisbossi's map, and in a smaller space, too." To Alpert this shows that "the political will exists to build some of the best transit in the world in a nation's capital city, while here, at least a significant part of one major political party would spend absolutely nothing on transit or the capital city."

There's something to this, but I once again need to return the fact that in terms of population density Washington is closer to Fargo than it is to Paris. People notice that central Paris doesn't have skyscrapers and want to start analogizing it to America's skyscraper-less capital. But Paris has over 54,000 people per square mile. If that many people lived in DC, we'd have well over 3.2 million people living in the city instead of about 600,000. And clearly if that were the case we'd have the tax base to support a much more expensive mass transit system.

The issue is that even leaving aside the issue of restricted building heights in the central business district, DC's zoning code mandates densities in the bulk of residential neighborhoods that are low by Paris standards. I think big-time heavy rail investment is a smart idea that's paid off for Paris, London, New York, Tokyo, Berlin and many other cities around the world. But the thing that makes heavy rail pay off is that it facilitates high densities, and high density facilitates high productivity. But it doesn't make sense unless you're willing to pair the construction with substantial relaxation of low-density zoning mandates. Otherwise it largely just functions as a subsidy to people who happen to live near the new train station.

Palestine Papers

I'd been holding off on writing about the "Palestine Papers" until my colleague Matt Duss could write the definitive Palestine Papers blog post and now that he's done it I'll just go link to it. Let me also offer up the column I wrote after visiting Ramallah:

Fayyad's achievements come either as gifts from Israel (in terms of reduced checkpoints and road closures) or from the U.S. and Europe in the form of money used to underwrite a massive growth in the state apparatus. He has no democratic legitimacy and has no way to deliver sustainable economic gains under the current circumstances of the occupation. Politically aware Palestinians understand what's happening all too well: More than one described him as a tool of the occupation rather than a leader of the Palestinian people. Nonviolent resistance organizers observed that Fayyad's strategy is predicated on engaging in essentially no resistance of any form. His economic-development strategy amounts to running a tight ship in terms of personal corruption, plus begging for scraps from Israel and America, which severely constrains his political options in a way that utterly destroys his credibility.

One can question the wisdom of a strategy that amounts to propping up a dictatorial Palestinian collaborator regime. But the simpler issue is that if this strategy is to work at all, there's a great deal more urgency to the situation than Israel or the U.S. seems to perceive. If Fayyad starts scoring big wins on the core issues soon, he could emerge as something of a Palestinian analog to Michael Collins, the Irish military commander who delivered independence to his country at the cost of selling out Northern Ireland's nationalists. If not, the Fayyad era is likely to go down as an Arab version of Marshall Pétain's Vichy France.

These documents further reinforce that we're in the "if not" scenario here and that Philip Wiess is probably the future of American Jewish thinking.

Fighting Pain vs Fighting Addiction

Over the weekend I wrote about how the war on drugs interferes with the war on chronic pain, and Stephen Smith has an excellent followup, taking note of talk on restricting hydrocodone/acetaminophen blends like Vicodin:

Regardless of the merits of this new wave of regulation, it's worth examining why Vicodin, which is a compound of the opioid painkiller hydrocodone and acetaminophen (a.k.a. Tylenol), is so popular to begin with. Reading The New York Times gives you the impression that it's simply a popular and effective medicine, but there's another benefit to the combination found in Vicodin over straight hydrocodone: It's less regulated.

Pure hydrocodone is a Schedule II drug under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act, whereas hydrocodone compounded with acetaminophen is a more loosely regulated Schedule III drug, supposedly for its lower abuse potential. Wishing to avoid greater scrutiny, doctors prefer prescribing Schedule III substances like Vicodin over purer Schedule II formulations which don't contain liver-damaging acetaminophen. But why does adding a sometimes-unnecessary ingedient make it difficult (but not impossible) to abuse? For the same reason that the FDA is now regulating it: Because it's poisonous, and can even cause fatal liver damage in the quantities necessary to sustain a heavy addiction. Researchers refer to it as an "abuse deterrent formulation"—the modern-day equivalent of the government spiking industrial alcohol during Prohibition. Except rather than blindness-inducing methanol, we now use deafness-inducing acetaminophen.

Opioid addiction is bad, and it's perfectly reasonable for policymakers to try to minimize its incidence. But short of dying, experiencing chronic pain is one of the worst things that can happen to someone. The correct ordering of priorities is to try to make sure that nobody suffering from treatable chronic pain goes untreated, and then try to minimize addiction risks within that framework. The view that people suffering pain should get relief subject to the binding constraint that we need to fight addiction has a nice Puritan logic to it, but it doesn't make any real sense.

Magical Thinking on Chinese Economic Policy

Robert Samuelson offers a familiar and largely accurate litany of grievances against Chinese economic policy and then concludes with a bold call for . . . something to be done!

The U.S. response has been mostly carrots – to pretend that sweet reason will persuade China to alter its policies. Last week, President Obama and Hu exchanged largely meaningless pledges of "cooperation." Alan Tonelson of the U.S. Business and Industry Council, a group of manufacturers, says U.S. policy verges on "appeasement." We need sticks. The practical difficulty is being tougher without triggering a trade war that weakens the global recovery. Still, it's possible to do something. The Treasury could brand China a currency manipulator, which it clearly is. The administration could move more forcefully against Chinese subsidies. America's present passivity encourages China's new world order, with fateful consequences for the United States and everyone else.

So I guess I don't disagree with this. After all, who could? Like Samuelson, I think we should adopt strategies that are more effective at getting the PRC to do what we want than are our current strategies. But like Samuelson, I think strategies that trigger a trade war that weakens the global recovery would be a cure that's worse than the disease. Do such strategies really exist? I'm not convinced. "Move more forcefully" and "brand China a currency manipulator"—what does that mean exactly?

Suppose you were the leader of a foreign country and you were very upset about some set of American policies that distort global trade patterns but are backed by politically influential constituencies in the United States. Farm subsidies or the embargo on Cuba, say. What would you do to make Barack Obama give in to you? What could you do? What would Washington Post columnists write in response to your coercive efforts? What would your domestic press say about you once your efforts failed? I think it's easy to overstate the range of potentially effective tools of coercion available to national leaders.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers