Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2439

January 25, 2011

Hydrocodone: A Dissent

Reader AC has more on turning your vicodin into pure hydrocodone:

Just wanted to tell you that the reader commenting on the ease of abusing hydrocodone-acetaminophen medication is incorrect. What he says about the dissolution in water of both chemicals is correct, but whether or not the acetaminophen is dissolved or not in water you drink is irrelevant – it'll get into yr system either way. To extract the hydrocodone and remove the one must perform what's called a cold water extraction – dissolving the pills in water, then cooling down the water so the acetaminophen crystallises. After filtration the resulting liquid will contain very little acetaminophen but retain the hydrocodone. As this takes less than an hour, it doesn't really change the point yr reader was making, but I thought it was worth pointing out nonetheless.

So be careful.

Revisiting the Safety Net

Lane Kenworthy's post arguing that there's lots more stuff the social safety net should be covering is a useful corrective to what I wrote here.

So in response to Kenworthy and to several people who emailed, let me rephrase my point. Let's assume we don't undertake any major new programmatic commitments. We don't expand early childhood education, we don't send a higher proportion of kids to college, we don't do comprehensive wage insurance, we don't increase redistribution to the poor, we don't offer paid family leave, etc. Instead we simply try to avoid reductions in service levels for our existing commitments. Well what happens is that to avoid cuts we need need increases. That's because the share of the population that's elderly is rising and the cost of health care and education is rising as a share of GDP. Paying too much attention to political debates can tend to obscure this. The reality, however, is that Barack Obama's tax proposals don't raise enough revenue to pay for George W Bush's spending proposals over the long run. Evolving over time to Danish levels of taxation will be difficult, and yet it'll be necessary just to maintain our current programmatic commitments. I think the CBO sometimes obscures this by not publishing state/local versions of its famous "Medicare costs will bankrupt us" chart.

That's all to say, in other words, that while there are new things I would like to see the government undertake realistically a large portion of the revenue would have to be taken out of existing commitments. Our health care cost structure is famously higher than anyone's else, so it's not like this is impossible. But saying "let's cut Medicare to pay for universal preschool" is, I think, a different sentiment from "let's expand the welfare state by creating a universal preschool program."

The Decline of the Publicly Traded Firm

A long Felix Salmon post boiled down to a single bold hypothesis: "the total number of listed companies, which has been falling steadily for a decade, will continue to fall for the foreseeable future."

I can't prove it, obviously, but I suspect he's right. There's always been something somewhat illogical about organizing the economy around publicly traded firms (I think Keynes said that investment decisions shouldn't be the byproduct of a casino) and innovations like high-frequency trading and ETFs tend to heighten the contradictions. Does anyone think the mainstream corporate governance model is a stunning success? Oftentimes I think we implicitly assume that no fundamental innovations in the institutional structure of representative market democracies will take place, but also this stuff was invented in the past and may well be superseded.

Breaking the News

The basic phenomenon is nothing new, but the only thing preventing me from saying that the ratio of articles about Rahm Emannuel's mayoral bid to information about Emannuel's views on urban policy is almost infinite is my strong suspicion that the denominator is actually zero.

Better Trade Stats Needed

Pascal Lamy, part of the dynamic duo of French Socialists charges with overseeing the global economic system, has a good op-ed on the problems with existing "country of origin" designations in trade statistics.

The way the current system works, if an iPad shows up on a dock in the United States of America we ask where the ship left from. The answer is China, so then we say an iPad costing such-and-such amount was imported to the US from China. The reality is that the iPad is itself made up of a bunch of different stuff, including physical components from all over Asia. But it's mostly made up of intellectual property and brand value that are made in California.

Now Lamy goes on from this observation to suggest that more accurate trade statistics might lessen anti-trade sentiment. I'm not as convinced. I saw an opponent of the US-Korea free trade deal pointing out this morning that many of the "Made in Korea" goods that will be imported under the agreement will, in fact, be largely assembled from China-made components. What I do think would happen under more accurate statistics is that people might get a better sense of how central petroleum is to America's trade deficit. Americans consume much more oil per capita than do the citizens of other developed countries, and we consume much more oil than we produce. That means that over the long run for the figure to balance we need to run a substantial surplus in things that aren't oil. We need to sell many more goods and services to foreigners than we buy abroad. We need to consumer less non-oil than we produce, which is true of all oil importers, but our uniquely high level of oil use makes this uniquely true of the United States of America. And I think it's crucial to understand that America's high levels of oil consumption are, in part, a hangover of policies from the days of yore when the US was a net oil exporter and promoting high levels of oil consumption was part of a mercantilist strategy.

Tim Pawlenty and the Rhetoric of Freedom

It's slightly on the silly side, but I think this Tim Pawlenty self-promotional video is ultimately pretty awesome:

I continue to be fascinated by the way in which the rhetoric of "freedom" is always so closely associated with authoritarian populist nationalist movements. Absolutely nothing in the imagery of the video or the policy agenda of the Republican Party is suggestive of freedom. It's full of flags and grim-faced folks and bourgeois respectability and military jets flying in tight formation. It's an ad from a conservative politician that's about exactly what an ad from a conservative politician ought to be about—about preserving a way of life against Muslims, freeloaders, sexual deviants, and other threats.

Contrast Pawlenty's video with an advertisement that's actually about freedom:

You could totally imagine Job Cohen using that music and those images to talk about how the Netherlands is the most successful country on earth because it's also the freest and actually meaning that Dutch people enjoy an unusually high level of personal freedom. And wouldn't he be right?

Psephology And the Academy Awards

I have little of substance to say about the Academy Award nominations, but the new voting system does raise a number of psephological issues.

People generally don't think in detail about this, but the way the awards work is that members of a given branch pick the nominees for any given category, and then the general membership votes on the winner. Consequently, the electorate for the "Best Director" vote and for the "Best Picture" vote is identical. And since in practice nobody ever says "I liked A better than B, but B was 'better directed'" the Best Director winner almost always wins Best Picture. The reason this doesn't always happen is that the electorate for the nominations is different, so there's usually some non-overlap in terms of the nominees. The winners are picked via "first past the post" plurality voting, so the preferences of strong partisans of marginal candidates can impact the outcome. In practice, though, the same movie almost always wins both awards. The new system of 10 best picture nominees changes this by ensuring that at least five non-nominees for Best Director will be nominated for Best Picture.

How Cuts Can Be Both Small And Devastating

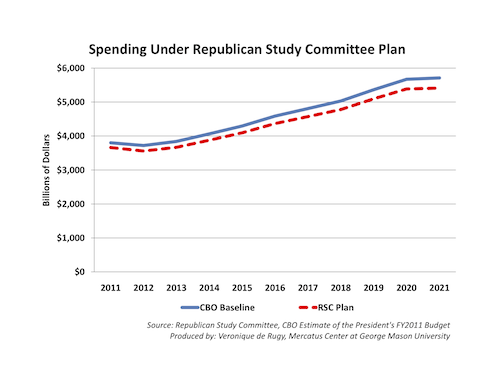

Veronique De Rugy evaluates the budgetary impact of the Republican Study Committee's proposed cuts:

Modest!

Nick Gillespie remarks:

De Rugy also rounds up a bunch of predictable comments about how the proposed cuts would be "devastating," "dramatic," and worse. Would that any of that were true.

I think this reflects a giant misunderstanding of how this works. If I were to recommend a 50 percent cut in what Jamie Dimon pays his maid that would both be a devastating cut in his maid's income and also a tiny cut in his overall expenditures. The RSC proposal rules out cuts in Social Security, the Department of Defense, Medicare, Medicaid, and farm subsidies. These programs combined constitute the vast majority of federal spending. Consequently, achieving even modest reductions in overall expenditure entirely out of the remaining non-defense discretionary budget requires devastating cuts.

Looking Back at SOTUs Past

I thought it was good of Ezra Klein to look back at his commentary on the 2010 State of the Union Address:

There are a fair number of speeches that Barack Obama has given that I can recall quite clearly. But the 2010 State of the Union isn't one of them. Looking back, I seem to have liked it well enough. And I apparently thought it had been sold as "a make-or-break speech for the president." But it wasn't. Single speeches virtually never are (for Obama, the 'race' speech in Philadelphia might be an exception). Presidents are too good at speeches to be broken by them, and Washington is too used to speeches to be transformed by them (though there was a time when that wasn't true). And the same goes for tonight's address.

I also loved the speech and also can't remember it at all. In my defense, though, I correctly predicted that it didn't matter at all:

I think Bob McDonnell gave arguably the best SOTU response I've ever seen—the choice to go with an audience is a big win. It still wasn't a good speech, per se, but it didn't suck. And that's a triumph.

As for Obama, I thought it was just great. A reminder that Obama is fantastic at delivering formal speeches and has a fantastic speechwriting stuff. The past twelve months are a reminder that giving fantastic setpiece speeches has limits as a political strategy. You drop out of speech mode into the realm of cold, hard vote-counting and I don't think anything's really changed in that regard.

This year the situation is perhaps slightly different if only because possible GOP presidential contenders will be watching and a bravura performance might cause someone to lose his nerve or whatever. I do think people have a persistent tendency to forget how good Obama and his speechwriting team are at delivering formal set-piece addresses, and then when they're re-surprised by his skills tend to forget how little this matters in practice.

Productivity, Housing, Wages, and "The Cost of Living"

One very typical line of dialogue in talking about politics goes like this:

LITERALIST: We need to raise taxes on rich people, the $100k and over crowd!

SUBJECTIVIST: $100k may be a lot of money in Kansas City, but try raising a family in New York or San Francisco on that and you sure won't feel very rich.

LITERALIST: Look, one hundred thousand dollars is double the median household income in the United States of America. If you're making twice as much money as the average household, you can't go whining about hardship.

SUBJECTIVIST: Feelings, nothing more than feelings.

LITERALIST: After all, the high cost of houses in high-cost areas reflects the fact that an apartment in Manhattan is a luxury good.

Brad DeLong has a couple of recent posts that play out some of this dynamic. But after reading some Ed Glaeser more recently, I think this whole line of inquiry is mistaken.

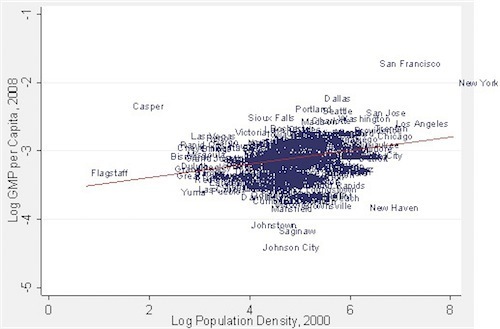

The issue is that high-density areas are more productive:

Since productivity is higher in denser areas, wages are also higher. So it's not at all clear that the guy earning $100k a year in New York could, in fact, take that salary to Kansas City with him. Meanwhile, in principle the price of housing ought to approximately equal the price of housing construction. The cost per square foot of building a 25-story apartment building is somewhat higher than the cost per square foot of building a single-family home, so the higher wages in New York ought to be partially offset by higher construction costs. In practice, however, the price of housing in New York is only very loosely related to construction costs. That's because there are large non-trivial* regulatory barriers to construction. On the flipside, during the urban disinvestment period of the 1970s and early 1980s it was possible to purchase real estate in many parts of New York City** for less than the cost of construction. And some households are beneficiaries of rent control legislation and the like.

The upshot is that on average the higher wages in New York should, in fact, be more or less offset by congestion costs and the higher cost of housing.

But that's only an average. In practice, the distributional consequences of supply constraints vary wildly. A person renting in New York City and earning $100,000 a year may in fact be "really" not that rich, despite his high income relative to the national median. The flipside of this is that he's probably much less good at his job than he believes, and is earning a substantial wage premium based on his willingness to bear the high housing costs. But someone who bought an apartment in New York in 1982 and now earns $100,000 a year is actually much richer than his income would suggest. People like this (i.e., people like a lot of my parents' peers) are really a kind of urban rentier class whose wage income may be pretty small relative to the financial value of the regulatory privileges they're receiving.

And the real point to be made about this isn't so much about how much taxes anyone should be paying as it is about how massively inefficient it is. If the restrictions on density were relaxed, we'd have more people living in high-wage, high-productivity areas and those places would be denser (meaning more productivity and higher wages) and housing costs would be lower relative to wages, meaning more disposable income. The point to recall is that the high per square foot cost of housing in New York and San Francisco isn't really the cost of "living" it's the cost of regulatory privilege.

(I thank Ryan Avent's discussion of WMATA for suggesting this analysis)

* By which I mean it goes well beyond conventional rules like the ban on child labor, basic worker safety, etc. that apply everywhere.

** And other American cities, with the precise time period varying from place to place.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers