Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2435

January 30, 2011

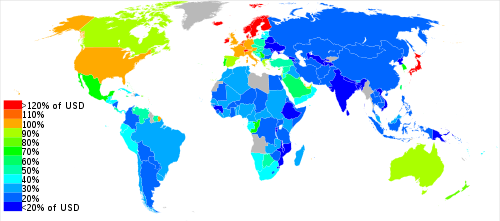

Fun With Purchasing Power Parity

Groceries are quite expensive at the Providenciales supermarket compared to what you pay in Washington, DC which induced me to want to find out if the price level overall is higher here or if it's just food. That led me to this neat map of Purchasing Power Parity all around the world:

Richer countries have higher price levels in general. But Japan is not richer than France, Germany, and the UK which makes its high cost of living evidence of a low-productivity service sector.

The Best of Times, The Worst of Times

Tyler Cowen responds to charges of pessimism:

If the numbers for median income growth are low we ought to take that seriously, as does Scott Sumner. We are not cheerleaders per se (BC: "I'm baffled why Tyler would focus on slight declines in American growth when the world just had the best decade ever." Is it then wrong to focus on any other problems at all? I also was one of the first people to make the "best decade ever" argument, which I still accept.) Medians also matter for the political climate, even though the median earner is not exactly the median voter. Adam Smith's welfare economics was basically that of the median, a point which David Levy has made repeatedly.

I'm also being called a "pessimist" a lot. Yet in my view our current technological plateau won't last forever. That's probably more optimistic than the Hacker-Pierson approach, which requires a Progressive revolution in economic policy (unlikely), although it is not more optimistic than denying the relevance of the numbers.

I more often get this from the other direction where people mistake my agreement with the assertion that 2000-2010 was about the best decade ever for humanity with undue complacency about the problems of the world. But the fact of the matter is that it can both be true that rapid catch-up growth in large population poor countries is a huge step forward for human welfare, and also true that developed countries in general and the United States of America in particular, seem to have run aground to an extent. Indeed, even though it's not rational for people in rich countries to feel threatened or upset about catching-up happening abroad, it's also very natural. We would probably feel better about the slow rate of growth in the US over the past 10 years if it had nonetheless been the fastest growth in the world. But, plainly, it wasn't.

The Fox Effect

Richard Ramsey writes about Fox Geezer Syndrome:

Over the past couple of years, I've been keeping track of a trend among friends around my age (late thirties to mid-forties). Eight of us (so far) share something in common besides our conservatism: a deep frustration over how our parents have become impossible to take on the subject of politics. Without fail, it turns out that our folks have all been sitting at home watching Fox News Channel all day – especially Glenn Beck's program.

The years 2009 and 2010 were a period of declining popularity for Barack Obama, for the Democratic Party, and for progressive politics in the United States of America. Under the circumstances, it's tempting to examine any particular trend in American political life that operated in parallel to this and see it as advantageous to conservative politics. Hence the skyrocketing popularity of a deliberate kind of political entertainment in which folks like Glenn Beck lie to gullible conservatives about what's happening in America appear to many as a form of successful political tactic. In reality, however, the declining popularity of Obama, Democrats, and progressives can be easily attributable to poor economic conditions. Now that trends have leveled off and Obama is back at 50 percent and we seem to be headed for a span of so-so growth I think we're going to find that while Beck has certainly carved out a lucrative business niche for himself, that in political terms creating a paranoid and misinformed base is not helpful.

Change At The Top

David Sanger and Helene Cooper explain the Obama administration's thinking in not directly calling for Hosni Mubarak to resign:

President Obama's decision to stop short, at least for now, of calling for Hosni Mubarak's resignation was driven by the administration's concern that it could lose all leverage over the Egyptian president, and because it feared creating a power vacuum inside the country, according to administration officials involved in the debate.

In recounting Saturday's deliberations, they said Mr. Obama was acutely conscious of avoiding any perception that the United States was once again quietly engineering the ouster of a major Middle East leader.

I hesitate to say much of anything about this because, again, what the heck do I know about Egypt. But given that the country is scheduled to have a presidential election in 2012, the terms of that vote rather than the disposition of Mubarak right now seem to me to be the key issue. Obviously, Egypt's presidential elections are shams. Appointing a new president for 18 months and then holding a new sham election doesn't do much good. What's really needed is concessions around the electoral process to give opposition candidates a fair chance.

1688: The First Modern Revolution

Given that use of the term "revolution" to describe a political regime change dates from the Glorious Revolution of 1688, it's ironic that the conventional wisdom has come around to the view that it wasn't a "real" revolution at all. In his 2009 book, 1688: The First Modern Revolution, Yale historian Steve Pincus tries to put the "revolution" back in the "Glorious Revolution."

As if often the case when an amateur dips into a historiographical controversy, at times Pincus seems to me to be reaching with his interpretation. But his point—which I think is well-taken—is that we should see the events of 1688 as one but one episode in a years-long process that really did constitute a Whig Revolution complete with revolutionary wars and a major change in the basic orientation of English economic policy. The parts of the book dedicated to arguing with other historians about how we should understand James II's agenda are kind of dull, and unfortunately this is where Pincus starts. But the latter parts about the Whig agenda and early liberal politics are fascinating. The Tory view that real wealth is based in land and hence is finite and merely shifted around rather than increased through exchanges isn't something anyone would admit to believing today, but I think it's fair to say that a kind of folk Toryism on this point animates a lot of thinking at all points in time. The fact that modern banking is really a kind of invention of statecraft and not a natural part of the exchange economy is important to understand even today and learning about its specific historical origins drives that home.

Service Without Servility

I wrote the other day about how most of the jobs of the future are likely to be pretty banal—think of categories of service sector work that people do today, and imagine a higher proportion of the population being engaged in them.

One response to this vision of the future is to deride it as saying that I'm trying to "convince those without that their future lies as the body servants of those with." But of course the whole essence of all economic transactions is that you're doing things for other people. Farmers are growing food for non-farmers. Carpenters are building houses for people to live in, and auto workers are building cars for the middle class to drive. Performing a "service" for someone else in exchange for money is no different from building something for someone else in exchange for money or from growing some food for someone else in exchange for money. But I think we have a cultural hangup around the idea that there's something inherently servile in the idea of service sector work. That it lacks the dignity that comes with manufacturing employment on an assembly line.

But while it's of course true that the very worst service sector jobs are in fact bad jobs to have, there's no reason to see this as being the case generally. We tend to acknowledge this by dignifying a certain sub-set of service sector work that requires advanced degrees as "professions" rather than "services." Hence your lawyers and doctors and architects. But consider this Planet Money host about a woman who's pursuing her dream of becoming a Lindy Hop instructor. I wish her well and don't think there's anything service or demeaning about sharing expertise in swing dancing with paying customers. And that's the point—if a smaller number of people are able to produce a larger number of material goods, then then "jobs of the future" will come in the form of more people doing this kind of thing, sharing their (labor intensive) skills and passions with interested members of the public in exchange for money.

January 29, 2011

WHPS: Who Cares?

Howard Fineman celebrates Jay Carney's elevation to the post of White House Press Secretary because it shows Barack Obama's understanding of the need to surround himself with savvy insiders:

[Obama] is setting up his reelection campaign back in Chicago, but that is an expensive piece of window dressing unlikely to convince people that he is somehow still, if he ever was, a guy from the heartland. David Axelrod and the gang will be back in the Windy City, but the operation will be run by a Chicagoan-cum-Washingtonian with national and even global ties — Bill Daley — and a cadre of the best and the brightest of the Clinton administration who came to the city to do good and stayed to do well.

Obama came to the White House in the manner of Jimmy Carter, with whom he was, early on, mistakenly compared. But while Carter never expanded his circle beyond the "Georgians," Obama has, with stunning swiftness, retooled his administration to play hardball in the D.C. League.

This seems to me to be a reference to a change that simply never happened; there was no point in time when the Obama administration was dominated by "Georgians." What's striking about the change between Rahm Emannuel and Bill Daley at the top is that the two guys share the exact same biographical qualities of being DC insiders who are also people Obama knows from Chicago. Beyond Emannuel, the key departed members of the Obama White House Mark One were Axelrod, Larry Summers, and Peter Orszag. Axelrod's being swapped out for David Plouffe and Summers & Orzag were never "Georgians." The entire argument that a change is happening really needs to rest on the Gibbs for Carney swap which, in turn, seems to rest on an almost comical overestimation of the role of the White House press secretary.

Apparently this overestimation is widespread in the press in a way that I can only hope reflects cynical source-greasing rather than genuine confusion. But I would say that a good rule of thumb is that whoever has a lot of time to spend batting around questions from the media is, by definition, not spending a ton of time offering input on questions of national significance.

Petropolitics in a Democratic Middle East

John Quiggin speculates on US foreign policy vis-a-vis a hypothetical post-authoritarian Middle East:

The point applies most obviously in relation to oil. The idea that the US can legitimately use its military power to ensure continued access to oil resources rests, in large measure, on the (not entirely unfounded) assumption that those controlling the resources are a bunch of sheikhs and military adventurers who happened to be in the right place, with guns, at the right time. Without the Arab exception, the idea of oil as a special case, not subject to the ordinary assumption that resources are the property of the people in whose country they are found, will also be hard to sustain.

Certainly if you were just to look at things in coldly rational terms, the resource-rich country the US should be seeking to dominate militarily is Canada, located conveniently next door. And, indeed, in the first half of the nineteenth century that's how hawkish American politicians saw things. But it would be politically unacceptable in a modern context to try to bully Canada or Norway into coughing up oil.

Egypt: The Known Knowns

I wrote a post on January 13 that I think looks pretty good today:

Just think of all the banal, publicly available factual information that's relevant to foreign policy and that most of us can't rattle off the top of our heads. What's the age structure of the population of Egypt? Is the Christian population growing faster or slower than average? Because of differential birth rates or differential emigration rates? Does Okun's law hold up there like in Canada, or has it broken down like in the United States? But if you tried to write an article about this in the popular press, nobody would care. A scoop about a "secret report" on Egypt would, by contrast, be a kind of news even if it didn't amount to much more than embassy gossip or slightly informed speculation.

That's not to say that anyone would, could, or should have predicted political turmoil in Egypt. But your best bet at predicting these things would come from being very well-versed in the publicly available information. Know the demographics, know what the staple foodstuffs are, know what's happening in the commodities markets, and you'll have some lead on where political instability is likely to happen.

Karl Marx, Real Business Cycle Theorist

Kudos to Benjamin Kunkel for trying to present an accessible Marxist account of the current financial crisis. I was struck reading the piece, though, by how similar the Kunkel/Harvery/Marx account of the crisis is to linguistically and ideologically quite different accounts from the right.

Essentially the Marxist and the real business cycle theorist are united in the view that these things happen and mass unemployment and prolonged periods of immiseration are just what happens in a market economy. The RBC stops there while the Marxist looks forward to the construction of an entirely new system along entirely new lines. The range of views associated with John Maynard Keynes and his followers or Milton Friedman and his followers says, essentially, no. A transient period of somewhat elevated unemployment could reflect a change in tastes—people decide they want fewer apples and more pears and various elements of the economic system need time to reshape themselves to fit the new conditions. But a prolonged period of widespread mass unemployment paired with a collapse in overall spending reflects something else. People haven't decided they want fewer apples and more pears, they've decided they want fewer goods and services and more safe liquid financial instruments. What has to happen in response is that governments need to create more safe liquid financial instruments—more dollars, more euros, more Swiss & British sovereign debt—until people decide they've had enough and want to increase their demand for goods and services.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers