Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2447

January 18, 2011

Free Market Health Care

I think it's a little bit strange that this week House Republicans will voluntarily cast a vote that can be characterized, 100 percent accurately, as authorizing insurance companies to refuse coverage to people on the grounds that they're in less-than-perfect health. Tough votes happen in congress all the time, but you don't normally ask people to walk the plank over something that has no chance of passing. After all, as Amy Goldstein notes the pre-existing condition problem is quite widespread:

As many as 129 million Americans under age 65 have medical problems that are red flags for health insurers, according to an analysis that marks the government's first attempt to quantify the number of people at risk of being rejected by insurance companies or paying more for coverage. The secretary of health and human services released the study on Tuesday, hours before the House plans to begin considering a Republican bill that would repeal the new law to overhaul the health-care system.

Something this helps highlight is the odd two-step that conservative opponents of the Affordable Care Act tend to do on the subject of what it is they want from the health care system. On the one hand, they take advantage of people loss-aversion and status-quo bias which works because most voters already have health insurance. On the other hand, to avoid simply defending an untenable status quo they assert that they have in their back pocket some free market solutions to our problems.

Unnoticed in this is that the only reason most people are insured today has to do with the non-market elements of the system. First, the tax code provides an enormous subsidy for employer-provided health insurance that ends up putting the majority of employed Americans into large risk pools at the expense of everyone who doesn't work full-time for a big company. Second, Medicare mops up the largest pool of non-employed people by giving single-payer health care to everyone over 65. Third, a regulation bans discrimination against people with pre-existing conditions as long as they maintain "continuity of coverage" as they shift from one employer to another. Fourth, COBRA allows people to maintain continuity of coverage even if they experience transient spells of unemployment. Fifth, Medicaid and SCHIP give coverage to many classes of poor people who'd otherwise be unable to afford it.

An actual free market approach to health care would require unraveling all of this and subjecting everyone to a world in which you can't get coverage if you're sick. Which is exactly how you would expect a free market to work. A pyromaniac is going to have a hard time getting fire insurance; if you say "give me some car insurance so I can polish off this bottle of vodka and go drive home" you're going to have a problem. There's no reason the market should provide health insurance to people with health problems, and there's every reason for the market to suspect that anyone who's asking for health insurance has a secret health problem.

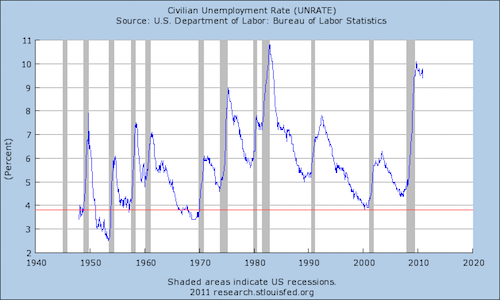

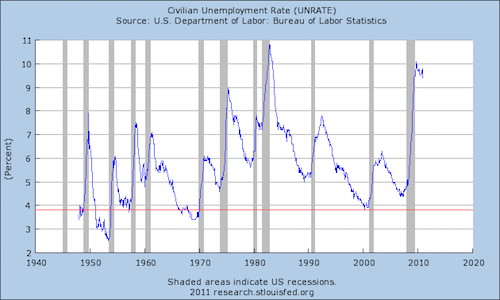

Jobless Recoveries and the Social Contract

Over the weekend, Kevin Drum blamed "jobless recoveries" on the collapse of the American social contract:

[I]n the past, holding onto workers through a recession was simply part of the social contract. Economically, it didn't make any more sense in 1955 than it does today, but firms did it anyway because it was expected of them. In union-dominated industries, contracts demanded this kind of behavior. In non-union industries, corporations did it as a way of keeping unions at bay (since unions had a much easier time organizing industries that provided lousy benefits). And white collar industries didn't feel that it was right to treat their workers worse than blue collar workers were treated. All of this conspired to create a social custom that bound workers and firms together.

This all evaporated in the 80s, of course, as younger workers largely got tired of dedicating themselves to a single company for life and corporations didn't feel like they could compete with rivals who were more ruthless about downsizing. As a result, workers are now fired much more quickly during downturns and hired back more slowly during recoveries. It's no coincidence that we first saw this pattern following the 1991 recession. It's just one more example of economic behavior which is, technocratically speaking, more efficient, but in which the benefits of that efficiency flow pretty much entirely in only one direction.

Putting my neoliberal sellout hat on for a second, the case for flexibility that Drum's leaving out would seem to be this. If you're an employer who's seen as having a social obligation to not let your workers go even if it's economically rational to do so, this is going to make you more reluctant to add new workers even if it's economically rational to do so. In the social contract between employers and employees, one party—the not-yet-employed—is cut out of the deal.

But then comes the punchline:

In the post-1980 policy regime, the business cycle has oscillated less frequently, but the depths of the recessions have seen higher-than-ever unemployment and the labor market peaks have become less impressive. And this, I think, is the real breakdown of the social contract. The idea of more flexible labor markets is that the "insiders" lose at the expense of the "outsiders" and the bosses only actually benefit in the short-term because profits tend to be competed away. But we have more outsiders than ever thanks to a Federal Reserve system that's very good at preemptively choking off inflation but not so good at preventing recessions. As of 2007, the story was that we'd achieved a "Great Moderation" of the business cycle via this combination of flexible labor markets and cautious monetary policy, but obviously that's not a viable characterization of the situation today.

Paul Krugman says the issue is in part that "engineering a recovery from postmodern recessions is much harder than engineering a recovery from a recession more or less deliberately inflicted by the Fed" but another way to put this might be that the Fed simply hasn't been doing a very good job. There's plenty of research out there, a fair amount of it by Krugman himself, about dealing with these "postmodern" recessions and the FOMC hasn't really done what the research suggests is necessary.

Pay to Play On Texas Inauguration Day

If you live in Texas, or if your professional life is in some way impacted by Texas public policy, you might like a meeting with Texas Governor Rick Perry. And he's happy to meet with you if you help throw him a lavish party:

The Republican governor and Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst were the featured attraction Monday night at an invitation-only soiree for donors giving as much as $100,000. Oil executives, beer distributors, lobbyists and big-dollar campaign donors — many with interests before the state — are providing the nearly $2 million for the swearing-in. In exchange, they are offered various levels of access. In addition to dinner Monday at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, where there were photographs with Perry, underwriters got VIP tickets to today's inauguration on the Capitol grounds.

As I wrote on Sunday, I think the corruption involved in this sort of thing is considerably clearer and more objectionable than with campaign contributions. Energy policy is a subject on which people have substantial good faith disagreements, and you would expect oil companies to back the election bids of candidates who hold views that are favorable to their interests. This creates a deplorable structural imbalance in politics, but it's not the same as bribing the politicians.

By contrast, picking up the tab for Rick Perry to throw himself a big party seems fundamentally similar to buying Rick Perry a nice car, paying for Rick Perry's daughter's sweet sixteen party, or passing him a garbage bag full of cash. Life in the state of Texas would proceed just fine if Perry's "inaugural gala" was him and a few close friends and allies going out to a nice dinner to and splitting the tab. The existence of a lavish party is fundamentally a private benefit, and having outside interests pay for it seems a lot like bribery. Perry is obviously not unique in this regard so I don't want to make it out like this is a particular slam on him. But I think the norms around this practice are screwed up and I happened to see this article this morning.

Tradeoffs in South Asia

Barack Obama's administration has, quite sensibly, continued the Bush administration's efforts to deepen ties with India. Indeed, the Obama administration has gone beyond what its predecessors have done and, again quite sensibly, endorsed a UN Security Council seat for India. Unsurprisingly, they don't love this plan in Pakistan (via my colleague Colin Cookman):

These apprehensions, which were conveyed by Army chief Gen Ashfaq Parvez Kayani to President Barack Obama, included the perceived US interest in transactional nature of ties with Pakistan; that war on terror had been imposed on Pakistan; alleged violation of Pakistan's sovereignty by the US; supposed US disrespect for Islam; much-touted American inner desire to defang and destabilise Pakistan; and its supposed indifference to Pakistan's strategic concerns particularly vis-à-vis India.

A senior official in a background briefing on Saturday pointed to Mr Obama's security strategy envisioning a greater role for India and Japan for Asian security and stability, and the growing support for Indian bid for UN Security Council's permanent seat as an indicator of a major shift in the dynamics of world order.

I think this points to one of the more underrated problems with US policy in the region. There's no reason for the United States to side with India over Pakistan or try to "defang" Pakistan, but I do think it's quite important for us to grow closer to India and to support perfectly legitimate Indian diplomatic aspirations. This seems to me to be clearly more important to our long-term interests than is the question of who controls which village in southern Afghanistan. But we're making a short-term commitment of money and American lives to a project in Afghanistan that's really premised on us doing whatever we can to obtain enthusiastic Pakistani backing.

January 17, 2011

Ideological Work

I largely agree with Steve Randy Waldman about the value of and need for "ideological work."

For my part, I'm continually baffled by the degree to which thought-leaders and politicians on the center-left think it's credible and/or political useful to present our agenda as wholly un-ideological and "pragmatic," somehow emerging magically through empirical study. Quine's Word & Object isn't about politics at all but it's full of valuable insights. All efforts to understand the world meld empirical and theoretical efforts, and all efforts to understand the world in a way that's politically relevant are thus necessarily ideological.

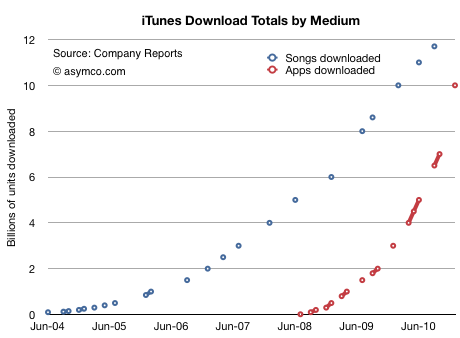

Vertical Integration

Horace Dedieu shows that aps are rapidly overtaking songs as Apple's most popular digital retail product:

The difference, of course, is that while I do buy both songs and aps from iTunes, I also buy songs from EMusic, from Amazon, etc. The iPod was launched as a device with a fairly general ability to play music files that competes with other music players, and then Apple also launched a music store that competes with other music stores. But Apple's app store doesn't work like that—it's not just a convenient venue for buying iOS devices, the devices have been designed so as to make Apple the exclusive retailer of iOS-compatible apps.

It's natural that players in the market will seek this kind of control over the digital retail distribution channel, since with zero marginal cost obtaining some form of monopoly power is critical. What's interesting is that the logic of the situation is that this sort of monopoly power ought to be obtained by the network operators (Verizon, AT&T, Sprint) who control the genuinely scarce resource of broadband spectrum. Apple's defeated that logic, thus far, by being smart slash lucky but in the long-run it seems to me that the rents will eventually flow to the operators.

The Presumption of Good Intentions

Josh Foust discusses one of the most severe problems with our recent national security policies, one that's difficult to discuss frankly in the current political climate:

The assumption of good intentions remains of the most critical failures of American imagination in both wars. I am at a loss for why this is the case—just about everyone who understands these things continues to beg the military to stop assuming Afghans know we have good intentions for the area, but it just hasn't sunk in yet. Actions speak louder than words, etc. It's not a hard concept to understand, but AMERICA GOOD is just not a given amongst locals. It's years past time people stop assuming this is the case. If you no longer think people just intuitively get the inherent goodness of America, then it becomes easier to see why they're pissed off at the destruction of their homes—not just "mud huts" but homes and a lifetime of memories and possessions (her continued inability to get that poor people care about their "mud huts" is worse than cringe-inducing). And, just as importantly, why it's not necessarily a good thing when they cooperate with you afterward.

To me, I think this is a critical way in which widespread "pro-military" attitudes in American media and political culture act, in practice, to undermine practical military effectiveness. There's a historical narrative about the United States being a force for good in the world whose military prowess is critical to the preservation of freedom that simply has nothing to do with the historical experience of large portions of the world. Nobody ever liberated Yemenis, or Pakistanis, or Venezuelans from Hitler or anything.

The Problem of Scale

James Fallows asks us to exercise our imaginations and ponder the scale of China:

If Americans wanted to imagine what it would take to be "strong" in the way China currently is, [Thomas Barnett] said, all we'd have to do is think of moving the entire population of the Western Hemisphere into our existing borders. Every single Mexican. (Rather than enforcing the southern border, we'd require everyone to cross it, headed north.) Every Haitian, Cuban, and Jamaican. Everyone from Central America. All 190 million from Brazil. And so on. Even the Canadians. China, by the way, is just about the same size as the United States, though a larger share of its land area is desert, mountain, or otherwise nonarable.

If we did that, we'd be up to about a billion people — and then if we also took every single person from Nigeria, and for good measure everyone in hyper-crowded Japan too, we'd finally be up to China's 1.3 billion size. At that point, like China, we'd have tremendous scale in everything. Rich people. Big businesses. A huge work force. Countless numbers of multi-million population cities. And we would also have a tremendous amount of poverty, plus pressure on resources of every kind, from water to food to living space. Just as China does now. Scale gives China some strengths. But it also creates tremendous challenges, as Americans would recognize if we thought about this prospect for even a minute. Seriously, reflect on this, and consider that it is China's reality now.

A useful exercise. And obviously we neither should, will, nor can do that. But I do think that what you might call the "national greatness" case for more immigration is underrated. All things considered, America is a pretty tremendous country and stands for good things in the world. Insofar as we tend to fall short in my view, it's on dimensions of conduct where the PRC does not excel. We're not talking about losing geopolitical influence to Norway. And, again, without being blind to the real problems with life in the US of A it's clearly the case that there are worse places to live and lots of people who'd like to come here. So insofar as we can recruit people to our standard—especially people who already possess skills, English-language fluency, or family ties to the country—the case for "bending the curve" of population growth upwards.

Most people don't realize this, but the United States continues to be a remarkably sparsely populated place. If the country as a whole had the same average population density as New Hampshire (!) it would contain about 522 million people and I don't think anyone would consider New Hampshire to be an example of dystopian.

Pas D'Ennemi à Gauche

Freddie DeBoer writes, among other things:

Many of the young, upwardly-mobile bloggers out there take their cues from Matt Yglesias and Ezra Klein. I don't begrudge either of them their policy preferences, even while I disagree with them. But each represents, in his own, the corruption and capitulation that comes with prominence and success in this culture. I genuinely don't know what the hell happened to Matt Yglesias. I long called him my favorite blogger. I've never mistaken him for someone who shares my politics. But he was, once, part of the resurgence of pride in leftism. He was one of the voices, in the midst of the Bush-era darkness, making it plain that he was unapologetic about being a creature of the left. In the last year or so, that stand has completely disappeared. He is now one of the most vocal of the neoliberal scolds, forever ready to define the "neoliberal consensus" as the truth of man and to ignore left-wing criticism. Indeed, I'm not sure that you could even understand that he has critics from his left, judging by what he chooses to discuss on his blog. This is a particularly cruel way to erase the left-wing from the discourse: to pretend that it doesn't exist.

I don't really know what it means to criticize a writer for holding that his own views are "the truth of man." Obviously, I agree with my political opinions and disagree with those who disagree with me. If I didn't agree I'd change my mind.

But one point that I agree with here, is that while I'll cop to being a "neoliberal" I don't acknowledge that I have critics to the "left" of me. On economic policy, here are the main things I'm trying to accomplish:

— More redistribution of money from the top to the bottom.

— A less paternalistic welfare state that puts more money directly in the hands of the recipients of social services.

— Macroeconomic stabilization policy that seriously aims for full employment.

— Curb the regulatory privileges of incumbent landowners.

— Roll back subsidies implicit in our current automobile/housing-oriented industrial policy.

— Break the licensing cartels that deny opportunity to the unskilled.

— Much greater equalization of opportunities in K-12 education.

— Reduction of the rents assembled by privileged intellectual property owners.

— Throughout the public sector, concerted reform aimed at ensuring public services are public services and not jobs programs.

— Taxation of polluters (and resource-extractors more generally) rather than current de facto subsidization of resource extraction.

Is this a "neoliberal" program? Well, this is one of these terms that was invented by its critics so I hesitate to embrace it though I recognize that the shoe fits to a considerable extent. I'd say it's liberalism, a view recognizably derived from the thinking of JS Mill and Pigou and Keynes and Maury "Freedom Plus Groceries" Maverick and all the rest. I recognize that many people disagree with this agenda, and that many of those who disagree with it think of themselves as "to the left" of my view. But I simply deny that there are positions that are more genuinely egalitarian than my own. I really and sincerely believe that liberalism is the best way to advance the interests of the underprivileged and to make the world a better place. I offer "further left" people the (unreturned) courtesy of not questioning the sincerity of their belief that they have some better solutions, but I think they're mistaken.

That's hardly a comprehensive reply to everything DeBoer wrote, but I hope it's an explanation of what the hell happened to me.

Things Looking Up In Ohio

Ohio, like most American states, has spent years groaning under the yoke of affirmative action policies. But along comes new governor John Kasich with the state's first all-white cabinet since 1962, solving the problem in one bold swoop. Now that real meritocracy has been restored to state government, though, things are finally turning around.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers