Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2450

January 14, 2011

Don't Look To The White House For Tax Reform

Lori Montgomery observes that Barack Obama's promise not to raise taxes on anyone in the bottom 98 percent of the income distribution means you can't do efficiency increasing tax reform:

President Obama's refusal to raise taxes for the vast majority of Americans will prevent him from pursuing a broad overhaul of the tax code and is making it difficult for him to achieve his goals for reducing the budget deficit, according to administration and congressional sources.

I've noted this before, but I think it's a real conceptual problem with this overall approach to tax politics. This is because the pledge prevents even reforms that make the tax code more progressive. In general, if you eliminate a tax credit and offset the revenue gain with a higher personal exemption, that will make most middle class households better off financially while also making the tax code more growth-friendly. That's good policy. But it's still the case that some middle class households would be better off with the old code.

That said, I don't think the specifics of the pledge are a huge deal in this case. That's because thinking of tax reform as a White House initiative is a mistake. If the President goes and leads the charge for tax reform, what happens is that tax reform passing becomes "a victory for the White House" and we start getting stories about "President Obama's goal of overhauling the tax code." And a proposal like that will be dead on arrival. Fundamental tax reform has a chance if and only if there's a bipartisan group of hardworking members of the House and Senate who sincerely want to reach consensus on a tax reform proposal. The role of the White House in a scenario like this is to be quietly encouraging, while making sure it doesn't become the tax that Republican who works on tax reform is immediately branded a traitor.

In general, people are eager to overrate the merits of intensive presidential involvement in difficult congressional fights.

Brooklyn Bucks

(cc photo by j_barry)

Here's a random paragraph from Paul Krugman's opus on the Euro:

I think of this as the Iceland-Brooklyn issue. Iceland, with only 320,000 people, has its own currency — and that fact has given it valuable room for maneuver. So why isn't Brooklyn, with roughly eight times Iceland's population, an even better candidate for an independent currency? The answer is that Brooklyn, located as it is in the middle of metro New York rather than in the middle of the Atlantic, has an economy deeply enmeshed with those of neighboring boroughs. And Brooklyn residents would pay a large price if they had to change currencies every time they did business in Manhattan or Queens.

I guess I wonder how inconvenient this would really be in 2010 as opposed to 1970. Individuals wouldn't, after all, really need to "change currencies" every time they went to Manhattan. You could buy things with your credit or debit card, and if you only had Brooklyn Bucks in your pocket, American dollars are only an ATM visit away. I think the real issue here isn't so much that it would be too inconvenient as that it wouldn't be inconvenient enough—getting US dollars and dollar-denominated financial assets would be so simple that US dollars would circulate widely in Brooklyn and Brooklyn Bucks would wind up being marginalized.

That's a long-winded way of saying that I think modern information technology has tended to erode the practical benefits of large currency areas and that the more "cashless" we get the more this will be the case.

Christians at War

Jeh Johnson is going to be getting some roundhouse condemnations for this:

Jeh C. Johnson, the Defense Department's general counsel, posed that question at today's Pentagon commemoration of King's legacy.

In the final year of his life, King became an outspoken opponent of the Vietnam War, Johnson told a packed auditorium. However, he added, today's wars are not out of line with the iconic Nobel Peace Prize winner's teachings.

"I believe that if Dr. King were alive today, he would recognize that we live in a complicated world, and that our nation's military should not and cannot lay down its arms and leave the American people vulnerable to terrorist attack," he said.

See Adam Serwer for the refutation .

What I'll observe is that this is a mere sub-set of the "Who Would Jesus Bomb?" problem in American public life. Martin Luther King was a Christian and a pacifist, and it certainly seems to me that any straightforward reading of the Gospel would support King's views on these matters. But though Christians are common in the United States, pacifists are exceedingly rare. What's more, in the US at least belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ is actually highly correlated with a tendency to embrace violent nationalism as an approach to the world. Consequently, people inclined to agree with the upshot of peace-loving Christian universalism of an MLK are relatively unlikely to embrace the Christian ethics that underly it, and vice versa.

Land vs Housing vs Real Estate

An offhand Scott Sumner remark says "here's a bad DeLong post, where he makes the common mistake of assuming a bubble prediction was correct, that was in fact wrong." DeLong is quoting a 2006 Paper Economy post that, in turn, cites a 2002 Wall Street Journal interview with Charles Kindleberger:

For weeks, Mr. Kindleberger has been cutting out newspaper clippings that hint at a bubble in the housing market, most notably on the West Coast. Nationwide, median home prices are up about 7% from a year ago, even though the stock market has tanked and the economy has floundered. Over the long term, economists agree, housing prices can't continue to outpace growth in household incomes. Mr. Kindleberger says he isn't certain there is a housing bubble yet, "but I suspect it is."

The trick with spotting real-estate bubbles, he says, is that they don't always spread. In 1925, for instance, real-estate prices in Florida soared and crashed, but that didn't spread to the rest of the country. Yet he notes that something is distinctly different about the nation's housing market today, when compared with 1925.

Sumner's point, I take it, is that in most markets if you bought in 2002 you're still in fine shape notwithstanding the recent crash.

But here's a different point. When you buy a house, you're typically buying two different things. On the one hand, you're buying some land. On the other hand, you're buying a physical structure that's located on the land. (If you're like me and own a condo, it's more complicated, but condo ownership is rare). The house plus the land is "real estate," although the house/land combo is often referred to on its own as "housing." Land and houses are, however, different things. And it might both clarify people's thinking and help retail real estate purchasers make better decisions to separate the two. Something really unusual (it might come to be regarded as an architectural masterpiece) would need to happen for the price of a house to increase over the long-term, whereas the value of a piece of land could go up or down for all kinds of reasons.

January 13, 2011

Endgame

If you don't really care:

— Ah, counterinsurgency; it's not a destroyed village it's "A Time to Build".

— Michael Chabon blogs and it's good.

— I think the message here is that Estonia is screwed.

— Supreme Court Justices try to think like criminals.

— Every once in a while I like to link to an insightful Steve Sailer post just to stir the pot and make people mad.

Kanye West featuring an awful lot of folks, "So Appalled".

The Pace of Change

Reacting to a story about the friendship between Debbie Wasserman-Schultz, Gabrielle Giffords, and Kirsten Gillibrand, Shani Hilton :

It's good that the women who are there have been able to support one another, but this is a reminder that women haven't made many inroads in Congress — or the congressional leadership — in nearly a decade. The 2010 election saw the first drop in women in Congress since 1979, from 93 to 90. It was also the first year since 1979 that women did not increase their ranks. There are currently 72 women serving as representatives: that's just over 16 percent of the 435 members. In the Senate, women fare a bit better, where 18 serve. The numbers have increased at a trickle, as Rutger's Debbie Walsh told CNN: "We tend to go up a few every cycle, three or four, maybe five seats, but women don't seem to be making any serious strides in terms of numbers."

I see the tactical and strategic case for emphasizing the negative—the pace of positive social change should always be higher—but that actually strikes me as a pretty remarkable record of steady progress. What's more, within the past ten years we also saw the first woman House Minority Leader and later speaker, we saw women head the DSCC and NRSC for the first time, etc.

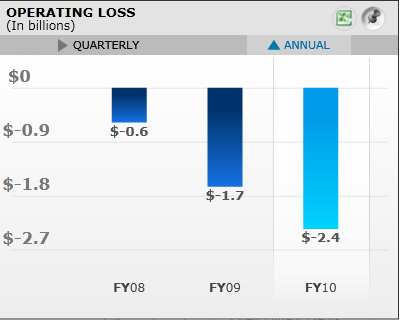

The Corporate Bureaucracy

Microsoft is a highly profitable firm. And it shows all signs of being able to continue to obtain large profits selling Windows and Office. By contrast, as Karl Smith observes, its "Online Services" effort to compete with Google sucks up large and growing quantities of cash:

Now it is possible that Microsoft will thrive, raise the dividend and deliver real gains to its shareholders. Yet, it is equally possible that Microsoft will lose in the new environment, go out of business or be forced to limit its dividend increases to less than the rate of inflation. In that case shareholders will lose money by having invested in Microsoft.

There is a simple way out of this. Shutdown the Online Services Division. Double or even triple the dividend and payout the profits to shareholders.

What's your guess on the probability that Microsoft will do this?

But, obviously, Microsoft won't do this. Successful companies basically never do this. And in particular companies like Microsoft with hugely successful businesses that will predictably decline in the future are especially loathe to just take profits while they can and accept eventual decline. The firms want to live! They want to grow and prosper. They want to reinvest profits in new lines of business. They want to conquer the world. The firm, in other words, is "captured by its corporate bureaucracy" and I agree with Smith that this is an underrated source of loss to the American economy.

I note that mitigating this problem is supposed to be one of the main advantages of fancy financial shenanigans. And there was a brief moment in which shenanigans were being deployed to reorganize conglomerates and unlock shareholder value. But that process seems to have essentially ground to a halt even as the quantity of shenanigans has exploded.

It's Always a Good Time to Regulate Well!

Ezra Klein and Kevin Drum have an interesting back and forth about Michael Mandel's idea that regulations should be somehow "counter-cyclical" which, in his formulation, basically amounts to saying they should be laxer during recessions.

The more I think about this, though, the more I think the insights here basically just amount to "it's always a good idea to have sound public policy." If you imagine some rule that's really important to preventing cans of beans from giving people botulism, that rule doesn't suddenly become less important in a recession. What's more it's hard to imagine a 12-month holiday on food safety rules for canned goods leading to a spike of job creation. It would mostly freak people out. Conversely, an unwise regulation like the rule in some parts of DC giving preference to franchised chain restaurants over non-franchised chain restaurants (or consider this) doesn't actually become worse during a recession.

I think that when there are downturns, public policy questions just become more salient. Good micro policies are, however, always really excellent things to have. Nonetheless, I don't think anyone really thinks the Italian labor market is holding up better than the American because of superior microeconomic policies.

Hunger and Inequality

Heavily subsidized Swiss cow (cc photo by LKM)

Tom Philpot goes long and global food shortages, but reaches a conclusion I'm not sure I entirely share:

But there's no reason to plunge into Malthusian anguish about a coming global population plunge. A lot people across the world are thinking hard about how to grow sufficient food without sucking dry the global water supplies or burning through fossil fuels like there's no tomorrow. For a bit of hope after imbibing a dose of Brown's bitter truth, check out WorldWatch's State of the World 2011 report, which surveys interesting sustainable-agriculture projects across the globe.

I agree that we don't need to plunge into Malthusian anguish either. And there's a more fundamental reason for that, actually. Global population is predicted to peak at around 9 billion people and I'm pretty confident we easily grow enough food to feed that many people right now. That's because eating meat is an extremely inefficient way of turning vegetation into food. If everyone gave up meat—or even just ate pork instead of beef—we'd have a big grain glut. The issue, of course, is that people don't want to give up meat. On the contrary, as the world gets richer people are shifting toward incorporating more meat into their diets. That, in turn, creates a kind of food chain gentrification problem for those individuals who aren't, personally, getting richer since it pushes up the price of grain.

The optimistic reading of that is that for all our horrible mismanagement of global water resources, it's really really unlikely that we'll reach a state of affairs where we're actually unable to produce the requisite calories to feed the world's population. The pessimistic reading is that producing enough food isn't enough—rapid growth in a handful of large poor countries can produce terrible consequences for poor people in other, still-poor countries.

Wilson Chandler vs Carmelo Anthony

Someone asked for more basketblogging, so I thought I'd take the opportunity to say that I think the value of acquiring Carmelo Anthony is being widely overstated in the basketball press. Like suppose you had to choose between Anthony and Knicks small forward Wilson Chandler, both of whom play 35 minutes per game this season.

Well if you care about rebounds, Anthony is doing quite a bit better, snagging 8.3 per game. His career average is only 6.3 but he's having a career-high rebounding year right now. Chandler grabs 6.3 rebounds per game. Advantage Anthony. They're the same in steals, Chandler blocks more (1.4 per game versus 0.6) and Anthony turns it over more than twice as often (1.4 to 2.9 per game). Then of course there's scoring. Anthony, I've been told by broadcasters, is the "best pure scorer in the game" reeling in an impressive 23.9 points per game while Chandler settles for a measly 17.7 PPG. But then again, Anthony's TS% is only .527 while Chandler's .579 is considerably more impressive.

Opinions differ about the merits of volume scoring versus efficiency. But Carmelo Anthony is currently paid $17 million to Chandler $2.1 million, so you would need to think Anthony was a lot better for a straight-up swap to look appealing. What's more, Anthony is currently 26 years old and looking for a maximum extension, meaning that four years from now you'll be paying him much more, though he's overwhelmingly likely to be a worse player by then. Chandler will be getting paid more four years from now than he's paid today, but he'll still be cheaper than Anthony and he'll be three years younger to boot. In general, it seems to me that NBA GMs underplay the problems with giving out max deals to Anthony-type players. Given the scale of the annual raises normally built into NBA contracts, a max extension for a 26 year-old is a kind of leveraged investment in a depreciating asset. There are circumstances under which that might make sense, but they're pretty rare.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers