Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2445

January 19, 2011

Endgame

I just want to know you're there:

— There's a fascinating symposium on Germany and the political economy of the EU happening at Crooked Timber.

— How easy will it be for computers to emulate human brains?

— Business would create more jobs if they had more customers.

— Does employment actually lag output or is output growth just too slow?

— "[L]ocals wondered why a group of unelected preservationists got so much say over the project."

I love this video for She & Him's "Don't Look Back".

K-12 Educational Efficiency

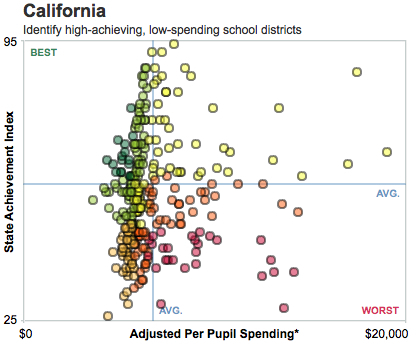

Today my colleague Ulrich Boser is releasing the results from a very important study of "productivity" in America's school districts. The project is complicated, so I encourage people interested in the subject to take a look at the report and the accompanying interactive tools. For illustrative purposes, here's a graph of California:

"Adjusted" per pupil spending means it's been "adjusted for differences in cost of living and student needs." The point here is just a pretty basic one, namely that there are enormous differences in outcomes that aren't attributable to spending in any clear or obvious ways.

(Ir)responsible Government

Brad Plumer notes that House Republicans are now discovering that the US Senate is a dysfunctional annoyance:

But guess who hates the Senate now? Earlier this morning, Republican House Majority Leader Eric Cantor kept insisting to reporters, "The Senate ought not to be a place where legislation goes into a dead end." (He said some variation of this three times.) Cantor's frustrated because the House is all set to repeal health care reform, and Harry Reid has said he's not even going to bother bringing the bill up for consideration in the still-barely-Democratic Senate. " The American people deserve a full hearing," Cantor said, "they deserve to see this legislation go to the Senate for a full vote."

I share Rep Cantor's pain on this point. But Cantor should spare a thought for the tactical advantages he's gaining here. The Affordable Care Act has, after all, a fair amount of interest group support. I bet hospitals in Cantor's district don't want to see it repealed. Nor do pharmaceutical companies. After all, one man's patient is another man's customer. But since repeal is just playacting for Fox News watchers, none of these groups are actually going to be pissed at Cantor or other pro-repeal House members. If repeal were a real possibility, there'd be much more intense anti-repeal lobbying and the whole situation would be much more complicated.

The Trouble With Bipartisanship

Katherine Skiba reports on the latest in pointless symbolism:

Defying tradition, Sens. Dick Durbin and Mark Kirk of Illinois will sit together during the State of Union address on Tuesday, a Durbin aide said Wednesday. Durbin is a Democrat and Kirk, a Republican. Normally members of Congress sit on opposite sides of the aisle, in the House of Representatives, for the speech.

The interesting thing here is that the symbolism does indicate the most plausible realistic basis for genuine bipartisanship—regional interest. Ideology aside, both Mark Kirk and Dick Durbin have an interest in twisting public policy so as to maximize the interests of Illinois vis-à-vis the rest of the country. But these kind of parochial interests are necessarily overweighted in a political system that's based on geographic representation. One of the positive features of partisanship is precisely that it cuts against this tendency and encourages members of congress to try to think in somewhat coherent, somewhat principled terms.

(I also note that Durbin is basically giving away the store here; a Republican in Illinois gains a lot from symbolic bipartisanship and Durbin gains nothing)

Taking Wellbeing Seriously

Mike Konczal wrote recently about Michael Walzer's Spheres Of Justice, which argues that egalitarians should care less about money and more about social meaning.

Konczal offers a gloss:

Inequality in education access, health care, life expectancy, quality of jobs are intrinsically linked to inequality in wealth and income with our poor levels of economic mobility in this country. Fairness and equality in our court and criminal justice system are largely a function of wealth. This economic stratification creates larger rigidities and barriers – some by accident, some by design – to further mobility and equality of opportunities in non-economic spheres. In this sense it can address control and power by the elite in a way that Rawls doesn't, and in a way that we could use right now.

Dara Lind sees it as to disentangle the two issues. I think this whole thing issue is best dealt with by simply adopting a more utilitarianish account of what matters in life.

If everyone earned the same amount of money but ten percent of the population suffered from chronic knee pain, that wouldn't be a perfectly equal outcome. What's more, merely guaranteeing the chronic knee pain sufferers access to affordable pain treatment wouldn't address the inequality unless the treatments actually cured knee pain. If they only worked a little, it would only help a little. If they didn't work at all, it wouldn't really help at all. The issue with chronic pain isn't that it occupies a separate sphere of justice, it's that it's so damn painful.

More generally, there's more to life than money. If you introspect, you'll see it's easy to think up experiences you wouldn't undergo in exchange for $10,000 a year in extra income. And I think everyone generally acknowledges this. Money can't buy you love and all that. But the policy discussion sometimes fails to acknowledge that in an affluent society many people suffer from problems that are more serious than lack of money, and that the problems themselves are what need addressing. Poor health is worse than poor "access to health care." It's scandalous that the poorest Americans often need to live in such high crime neighborhoods, but what really stands out about the USA in this regard isn't our housing policy or our gini coefficient but our very high murder rate.

Is Repealing the Affordable Care Act Secretly About Replacing It With a Different Secret Law?

In a word: No.

But don't tell wonk-turned-hack Douglas Holtz-Eakin who explains:

Replacing PPACA with real health-care reform that delivers quality care at lower costs. That is what the repeal vote is really about.

I always forget if I'm allowed to use the word "bullshit" on an official CAPAF website (that was a mention—thanks Professor Goldfarb!), but I think this is best analogized to the solid waste of a male bovine. This just isn't how public policy works. We change (or "replace") laws all the time, and it doesn't happen by first repealing predecessor laws tout court and then gesturing vaguely at a replacement. My guess is that Holtz-Eakin has a bunch of ideas about ways to improve health care policy in the United States relative to the post-ACA status quo. My guess is that I even agree with some of those ideas. The way to get those ideas enacted is to start explaining them to the press and the public and start talking to members of congress about turning them into bills.

At this point I'm not actually sure what the repeal vote is "really" about, but it's definitely not about starting concrete conversations about further changes to the American health care system.

The Corporate Recovery

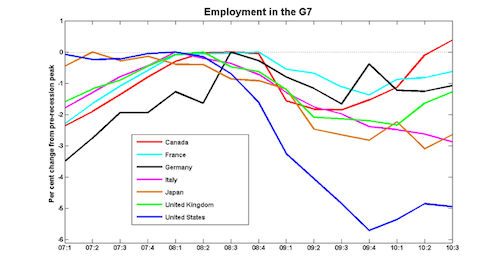

David Leonhardt reflects on America's corporate recovery:

The gross domestic product here — the total value of all goods and services — has recovered from the recession better than in Britain, Germany, Japan or Russia. [...]

Relative to the situation in most other countries — or in this country for most of the last century — American employers operate with few restraints. Unions have withered, at least in the private sector, and courts have grown friendlier to business. Many companies can now come much closer to setting the terms of their relationship with employees, letting them go when they become a drag on profits and relying on remaining workers or temporary ones when business picks up.

Just consider the main measure of corporate health: profits. In Canada, Japan and most of Europe, corporate profits have still not recovered to precrisis levels. In the United States, profits have more than recovered, rising 12 percent since late 2007.

On some level, though, this still looks to me like aggregate demand. Normally highly profitable firms would attract lots of capital and expand rapidly. People don't just sit around saying "what a highly profitable store I have here, let me count my money"—they try to franchise and get richer and richer. The exception is that if you expect generally depressed economic conditions then the mere fact that you're running one highly profitable store may still leave you doubting that a second store would make money. And, after all, with American households debt-constrained and many households suffering reduced income due to unemployment it seems quite reasonable to think that even profitable firms may not have expansion opportunities. You need to raise demand expectations by putting money into people's hands.

That said, what I think is clear is that a country with an institutionally stronger union movement wouldn't have let the current situation come to pass. What happened in Germany is basically that faced with a political culture that's absolutely terrified of stimulus, they worked out a labor-capital bargain that avoided mass unemployment even in the face of very poor GDP performance. It's possible that a hypothetically stronger labor movement in America would have worked out such a deal, but also possible (and more, I think, in keeping with the American character) that it simply would have demanded more stimulative policy and we'd have both lower unemployment and higher real output. As it stands, though, America's weak labor movement is concentrated in health care and the public sector so the bulk of its reduced store of ammunition has been focused on those elements of the economy.

Max Boot Learns About Collective Action And Free Riding

Via Justin Logan, Max "the most realistic response to terrorism is for America to embrace its imperial role" Boot is peeved that other people won't pay for our imperial endeavor in Afghanistan:

What irritates me about the whole situation is that it is the U.S. that has to pick up the tab. Our troops are already doing the bulk of the fighting. Why don't our rich allies — e.g., Japan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, France, Italy, Germany, Britain — pay for more of the cost of training? Some of those countries have made sizable troop contributions; others haven't. But the U.S. has done more than any of them in terms of fighting the Taliban directly. Why do we have to do so much more than the rest of them in financing the Afghan Security Forces too?

Then in the very next paragraph he offers up the explanation:

I should note that their failure to ante up should not be an excuse for us to walk away. This is not an act of altruism; it is very much in America's national-security interest to have a functional and effective security force in Afghanistan to prevent a Taliban/al-Qaeda takeover. Our security perimeter runs right through the Hindu Kush.

Look, obviously if the only consequence of Japan failing to pay for the training of Afghan Security Forces is that America does it instead then of course Japan isn't going to do it. There are presumably an array of things the Japanese government would like to spend money on, and most of them aren't things the US will pick up the tab for if Japan doesn't do it. So Japan will spend money on advancing Japanese priorities. What else should they do?

A large country is bound to generate a certain amount of free riding, but the upshot of Boot-style policies of whining followed by unilateralism followed by whining followed by unilateralism is a shortcut to national decline and insolvency.

Increasing the Money Supply

So today's Living Social Deal is that you pay them $10 and they give you a $20 Amazon gift card. Since there are such a wide variety of goods for sale on Amazon, Amazon store credit (especially in smallish quantities) is very cash-like, so a $20 for $10 swap is, in effect, a form of monetary expansion. And everyone knows I favor more expansionary monetary policy. So I'd encourage you to click here and take advantage of the offer even were it not for the fact that if three of you do so I'll get my gift card for free. Although, to be fair, the prospect of me getting a free gift card only makes the policy even more expansionary.

Is Our College Students Learning

A groundbreaking study (in terms of its sample size and rigor) finds that a large minority of college students don't really learn much in college. I've seen this written up in the mass media in a few sensationalistic ways (I saw a CNN chyron about "Is College Worth It?") all of which seem to me to involve sweeping away the two key broad points here:

— The higher education establishment does scandalously little of its own accord to try to measure learning.

— The problems here are clearly concentrated in specific sub-groups of students and schools and don't say much of anything about "the value of college" in a general sense.

I recommend analyses from Kevin Carey and Richard Kahlenberg who both delve deeper into the details.

Per Carey:

After controlling for demographics, parental education, SAT scores, and myriad other factors, students who were assigned more books to read and more papers to write learned more. Students who spent more hours studying alone learned more. Students taught by approachable faculty who enforced high expectations learned more. [...] Students majoring in the humanities, social sciences, hard sciences, and math—again, controlling for their background—did relatively well. Students majoring in business, education, and social work did not. [...] The study found that students whose financial aid came primarily in the form of grants learned more than those who were paying mostly with loans. Debt burdens can be psychological and temporal as well as financial, with students substituting work for education in order to manage their future obligations. Learning was also negatively correlated with—surprise—time spent in fraternities and sororities.

Kahlenberg focuses on the fact that these factors, combined with peer effects, seem to indicate that the more selective colleges are in fact better at generating learning:

Controlling for a range of individual student characteristics, including academic preparation, the authors find that students at selective colleges make stronger gains on the CLA—which measures critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills—than those at less selective institutions. Selective institutions are defined as those in which students at the 25th percentile have a combined math and verbal SAT score above 1150, and less selective are those in which students at the 25th percentile have a combined score below 950.

Unfortunately, however, the way most "selective" schools handle their admissions processes the overwhelming majority of the students who benefit from their educational services are the people with the least objective need. Elite schools that take their social mission seriously must act to diversify their student bodies. But of course the less-selective schools necessarily serve a larger group of people, so there's a need to reform their practices. They can't recreate the peer group effects of the selective schools, but they can be reformed so as to recreate the combination of high academic standards, engaged faculty, and lessened financial burden that are the characteristics of high student performance.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers