Alexander Laurence's Blog, page 2445

June 23, 2014

New Child of Lov music video emerges for "One Day ft. Damon Albarn

POSTHUMOUS MUSIC VIDEO FOR THE CHILD OF LOV'S "ONE DAY FT. DAMON ALBARN" EMERGES VIA SPIN Towards the end of 2013, The Child of Lov passed away at the age of 26. At the time, he had just released his debut album to critical acclaim and was preparing a stage show complete with full band, dancers, costumes, and imagery. Just prior to his passing, a music video for "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" was commissioned for the American director Christine Yuan; however, The Child of Lov would never see the video himself. Yuan had not met him nor did she know about his illness when she made the video but she clued in on the song's lyrics to find inspiration - "Hold me until the morning. Hold me until the morning. One day baby I got to die and I lie down." The Child of Lov was a prolific modern soul man who produced a large amount of work in a variety of mediums during the short time he was active as an artist. His legacy lives on through his music, poetry, and visual art. Watch: "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" -http://youtu.be/OPphaUiYssc

Towards the end of 2013, The Child of Lov passed away at the age of 26. At the time, he had just released his debut album to critical acclaim and was preparing a stage show complete with full band, dancers, costumes, and imagery. Just prior to his passing, a music video for "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" was commissioned for the American director Christine Yuan; however, The Child of Lov would never see the video himself. Yuan had not met him nor did she know about his illness when she made the video but she clued in on the song's lyrics to find inspiration - "Hold me until the morning. Hold me until the morning. One day baby I got to die and I lie down." The Child of Lov was a prolific modern soul man who produced a large amount of work in a variety of mediums during the short time he was active as an artist. His legacy lives on through his music, poetry, and visual art. Watch: "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" -http://youtu.be/OPphaUiYssc

www.thechildoflov.com

Towards the end of 2013, The Child of Lov passed away at the age of 26. At the time, he had just released his debut album to critical acclaim and was preparing a stage show complete with full band, dancers, costumes, and imagery. Just prior to his passing, a music video for "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" was commissioned for the American director Christine Yuan; however, The Child of Lov would never see the video himself. Yuan had not met him nor did she know about his illness when she made the video but she clued in on the song's lyrics to find inspiration - "Hold me until the morning. Hold me until the morning. One day baby I got to die and I lie down." The Child of Lov was a prolific modern soul man who produced a large amount of work in a variety of mediums during the short time he was active as an artist. His legacy lives on through his music, poetry, and visual art. Watch: "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" -http://youtu.be/OPphaUiYssc

Towards the end of 2013, The Child of Lov passed away at the age of 26. At the time, he had just released his debut album to critical acclaim and was preparing a stage show complete with full band, dancers, costumes, and imagery. Just prior to his passing, a music video for "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" was commissioned for the American director Christine Yuan; however, The Child of Lov would never see the video himself. Yuan had not met him nor did she know about his illness when she made the video but she clued in on the song's lyrics to find inspiration - "Hold me until the morning. Hold me until the morning. One day baby I got to die and I lie down." The Child of Lov was a prolific modern soul man who produced a large amount of work in a variety of mediums during the short time he was active as an artist. His legacy lives on through his music, poetry, and visual art. Watch: "One Day ft. Damon Albarn" -http://youtu.be/OPphaUiYsscwww.thechildoflov.com

Published on June 23, 2014 13:04

Depeche Mode - Delta Machine Remixes remixes

Out today: Depeche Mode - Delta Machine Remixes on Boysnoize Records

(Beatport only release for sale here HERE)

i-D Magazine premiered "Alone" (Djedjotronic Remix) HERE

Stereogum premiered "My Little Universe" (Boys Noize Remix) HERE

(hi res HERE)

Depeche Mode - Delta Machine Remixes

1 - My Little Universe (Boys Noize Remix)

2 - Alone (Djedjotronic Remix)

Today, Boysnoize Records exclusively release 2 stunning Depeche Mode remixes from last year’s highly acclaimed Delta Machine . "My Little Universe" and "Alone" receive the deluxe remix treatment they deserve, with Alex Ridha AKA Boys Noize himself working his magic on the former and fellow BNR buddy Djedjotronic completing the stellar line up with a with a suitable dark and brooding, techno affair. Stereogumexclusively revealed the Boys Noize "My Little Universe" remix HERE and it's free to share HERE. i-D Magazine premiered Djedjotronic's "Alone" on Friday HERE and it's free to share HERE.

The Depeche Mode remixes are exclusively for sale via Boysnoize Records only on Beatport HERE.

Delta Machine is the English band’s 13th studio album and was released by Columbia and Mute Records in March 2013. The record marked the end of a trilogy of records produced by acclaimed producer Ben Hillier and is considered by many as their most powerful, gothic, twisted, electronic album since Violator. The release of the remixes continues Ridha’s musical relationship with the band, his space age version of Personal Jesus having featured on Boys Noize – The Remixes back in 2011.

It has been a busy past year for Alex Ridha AKA Boys Noize, touring the world extensively and releasing an EP as Dog Blood and Out of The Black – The Remixes that saw Justice, The Chemical Brothers, Blood Diamond, Jimmy Edgar and more re-calibrate some of his own techno patterns. With the announcement of another world tour this year, and a string of further releases from his BNR blueprint, the Boys Noize machine is prolific as ever.

‘The main idea with this remix was to play with the contrast between intimate melody and claustrophobic rhythm. It's my attempt to translate the duality of feelings that is present in the original song.’ Djedjotronic

French born and Berlin-based label mate Jérémy Cottereau AKA Djedjotronic has been equally busy over the past few years. Since the release of his fifth record Walk With Me in 2012 on BNR he has charted at number 1 on beatport with analog bomb "Uranus" and remixed Gonzales, UNKLE, Tiga, Etienne De Crecy, Chromeo and Miss Kittin to name a few - his trademark insane techno sound with pumping computer beats, instantly recognisable.

(Beatport only release for sale here HERE)

i-D Magazine premiered "Alone" (Djedjotronic Remix) HERE

Stereogum premiered "My Little Universe" (Boys Noize Remix) HERE

(hi res HERE)

Depeche Mode - Delta Machine Remixes

1 - My Little Universe (Boys Noize Remix)

2 - Alone (Djedjotronic Remix)

Today, Boysnoize Records exclusively release 2 stunning Depeche Mode remixes from last year’s highly acclaimed Delta Machine . "My Little Universe" and "Alone" receive the deluxe remix treatment they deserve, with Alex Ridha AKA Boys Noize himself working his magic on the former and fellow BNR buddy Djedjotronic completing the stellar line up with a with a suitable dark and brooding, techno affair. Stereogumexclusively revealed the Boys Noize "My Little Universe" remix HERE and it's free to share HERE. i-D Magazine premiered Djedjotronic's "Alone" on Friday HERE and it's free to share HERE.

The Depeche Mode remixes are exclusively for sale via Boysnoize Records only on Beatport HERE.

Delta Machine is the English band’s 13th studio album and was released by Columbia and Mute Records in March 2013. The record marked the end of a trilogy of records produced by acclaimed producer Ben Hillier and is considered by many as their most powerful, gothic, twisted, electronic album since Violator. The release of the remixes continues Ridha’s musical relationship with the band, his space age version of Personal Jesus having featured on Boys Noize – The Remixes back in 2011.

It has been a busy past year for Alex Ridha AKA Boys Noize, touring the world extensively and releasing an EP as Dog Blood and Out of The Black – The Remixes that saw Justice, The Chemical Brothers, Blood Diamond, Jimmy Edgar and more re-calibrate some of his own techno patterns. With the announcement of another world tour this year, and a string of further releases from his BNR blueprint, the Boys Noize machine is prolific as ever.

‘The main idea with this remix was to play with the contrast between intimate melody and claustrophobic rhythm. It's my attempt to translate the duality of feelings that is present in the original song.’ Djedjotronic

French born and Berlin-based label mate Jérémy Cottereau AKA Djedjotronic has been equally busy over the past few years. Since the release of his fifth record Walk With Me in 2012 on BNR he has charted at number 1 on beatport with analog bomb "Uranus" and remixed Gonzales, UNKLE, Tiga, Etienne De Crecy, Chromeo and Miss Kittin to name a few - his trademark insane techno sound with pumping computer beats, instantly recognisable.

Published on June 23, 2014 10:55

Schonwald - Rays

Live dates Schonwald

Live dates Schonwald26/09 : Paris, Le Klub (+ guests)

04/10 : Lisbonne, A Comisao

This week, we are very glad to announce the release of Schonwald's new single, Rays, on June 24, 2014.

Spearhead of the Italian dark scene renewal, Schonwald, based in 2009 by Alessandra Gismondi and Luca Bandini in Ravenna, knew immediately how to find a just balance between electricity and sensualism, with a lot of deep and hypnotic basslines, synthetic striations and noisy acid guitars, mixing minimal wave drought and post-punk sweatiness.

This first collaboration between the band and Anywave contains two new titles and can be listened as a true 7" summer single : on the A-side, Rays is a cold-pop spiral, coming with a strange video in black and white, shot between a forest and the Adriatic Sea, winking to Antonioni's Deserto Rosso; on the B-side, Lower Lovers goes for a ride between The Normal and the early Cocteau Twins.

Rays video : http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y5RHl9D5MWE

Rays prefigures next Schonwald's album (out in September), we 'll keep you posted about very soon.

Press review :

"Schonwald are invading France at the end of June, with a hypnotic and psychoactive single, Rays, who would easily make The KVB or Soft Moon humble. Expect the walls to shake during all the good DJ sets in Paris this summer" - Villa Schweppes, June 2014

"Rays is an hypnotic post punk / new wave track, the frail vocal line is both haunting and enthralling. The drum machine beat drives the track over a wash of synths and pulsating bass. The sinister tone to the track makes one that you’ll revisit countless times. The minimalist electro deceives the complexity on display, new nuances and beats will surface one each listen." - Alt Dialogue, June 2014

Published on June 23, 2014 10:45

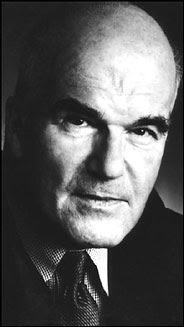

Gordon Lish Interview

Confessions of a SolipsistWhile DeLillo hides, Lish pontificates

Gordon Lish Interviewed about the world of Fiction and the burden of The Reader looking over his shoulder

by Alexander Laurence

Lish has taught fiction classes for 38 years, but now he has retired. He has hung out with writers like Don DeLillo and Cynthia Ozick, and has inspired many writers by his fiction workshops. Many writers have even claimed to have taken his classes who may have not been there. Whether yes or no, Lish is known as an editor, at Esquire Magazine and at Knopf, and now as a writer of some compelling works of fiction, starting with Dear Mr. Capote, up to recent works such as Epigraph and Self-Imitation of Myself. How I became interested in Lish recently was that I had heard he and DeLillo meet once a week, watch movies, drink and talk about women. I wanted to join them on one of these nights but DeLillo refused to join us. As I entered the Upper East Side abode of Mr Lish, with the photographer, he told us to remove our shoes, which we did, and ended up having a conversation for over two hours. Here is some of our talk.-------------------------------

AL: As far as the field of creative writing goes, you are a person who is known to a lot of younger writers, whether they have taken classes by you or not. Can you talk about your influence on these writers?

GL: I have taught at Yale, NYU, and Columbia. I used to teach week-long seminars and three-day seminars in various cities. I have taught privately. I used to teach two days a week at NYU. I would have about thirty students. At some point I wanted to teach longer hours. I ended up teaching as long as ten hours.

AL: What do you think of academic writing? Were you teaching a certain esthetic or focusing on a certain type of writing?

GL: Absolutely. You have to pay a lot of money to find that out. (laughter). I have been linked to Minimalism, but I have also sponsored Harold Brodkey and Cynthia Ozick. This is a convenience for people who don't want to comprehend these matters. Minimalism has nothing to do with it. Amy Hempel once wrote an article for Vanity Fair where she was arguing for this esthetic, which she understood to be the one that I was promoting. She said "Well, it's just leaving out the uninteresting parts." My take on these matters hardly could be reduced to writing or information. I teach people how to manage to make a totality, a totalizing effect out of singularity. This term is also used in Gilles Deleuze's Difference and Repetition. It's the means by which one dilates the origin into destination. I'm very specific about that. These poetics do not confine the result, but they tend to potentiate any result. There has, on the other hand, emerged an industry of writing. The Quarterly still receives mail after being defunct for three years. Before I threw stuff away I look at things sent in and there are still people who are delighted to give you their pedigree. They offer a recitation of where they published, where they studied, and often these people are teachers of writing. More often than not, they are teachers of writing, and you can't believe that they are writing.....

AL: As an editor and publisher, has a writer's resume or history ever mattered to you?

GL: Oh no. I throw it out. I don't look at it. If I do look at it now, it's just to share the ironies of it with my students. It's comical.

AL: Do you read a page?

GL: I don't even read a page. Less than a sentence. I fancy myself being able to read a page without reading a page. There's a look that good writing has, and I have a talent for seeing it. At Esquire Magazine, I used to look at a thousand pieces of unsolicited mail a week. I do think that there is a painterly aspect to the page, in the hands of a literary artist, or it's not there. I think it's either the typewriter producing these utterances, or it's a peculiar psychological or emotional presence. It's either coming out a sense of the error that art is, or persons who think they can get it right. Those people think writing is sounding like everybody else. They don't understand that real writing is sounding like only you can sound. I don't do a lot of reading, but I do a lot of looking.

AL: What do you think of the role of the writer presently? I know that Don DeLillo has written a piece about history and fiction. Does the writer have a social responsibility?

GL: DeLillo can look at things and get them right. That is to say, get them wrong, and by getting them wrong, making them stronger. I am not competent of looking at things. All I am able to look at is language, and behavioral features in myself, as occasions to fit the language to. If I tried to do what DeLillo does, or even render that bench stoop, I wouldn't have the ability and I wouldn't have the enthusiasm for the task. I wish that I had the strength of what DeLillo's texts exhibit to the world, and convey to others a sense of what ones looking at. I follow Walter Pater's view of the object only exists as a means for the subject to enact himself. In fact, I go further, and say that you, the subject, are only present to the object because of the nature of the subject. I only see anything because of the man I am. Everybody is looking at something else. I tend to be autistic and do things an autistic person does and which is failing to see what is central to the event, and instead sees something peripheral to it. If we went to see a stage play, you might find me distracted and looking at someone in another row or looking at the curtain, and not looking at the drama on-stage. I tend to be very solipsistic and very shut off from other people. The only objectivity, authenticity, stability there is to the extent that any of these words would apply to what I'm about to say, is in language itself, but of course the language is not stable.

AL: It's really strange that in the new book you deal with so few elements, there's a solipsistic monologue aspect, but at the same time you are referring back to the text as text, whatever it's called, "self-reflective," and I'm often reminded of Italo Calvino's work. An episode may be set off by a mundane occurrence in life, which eventually disappears into the writer's voice.

GL: The two new books which will be coming out in the near future, Arcade, and Chinese, and certainly the one that I am working on now, all represent a more considerable descent into the very terms you just described. These books become more and more self-reflexive. And how should I say, capricious, and caught up in the paradox of the reader becoming a burden. Yet what are you doing it for unless you are positing a reader? At least one person has to read. I imagine one among the mighty dead, like Beckett or Joyce. I might be happy if Kafka is the reader. I might not be too happy if someone in my immediate family is the reader. Besides my students, I think that Cormac McCarthy, Cynthia Ozick, and Don DeLillo are the only writers who I care about, and I would like them to be my readers.

Published on June 23, 2014 10:41

Death Has No Dominion Self-Titled out now on SQE

Death Has No Dominion Self-Titled Album Out Now On SQENew York Times T Magazine Premieres "Coming Like A Hurricane" Video Watch: "Coming Like A Hurricane" video via New York Time T Magazine orYouTubeListen: "Coming Like A Hurricane" via Wondering Sound or SoundCloud

Watch: "Coming Like A Hurricane" video via New York Time T Magazine orYouTubeListen: "Coming Like A Hurricane" via Wondering Sound or SoundCloud

Danish-duo Death Has No Dominion's self-titled album is out now on SQE. The New York Times T Magazine chatted with the band about the new album, their roles at the Danish clothing brandLibertine-Libertine, and the making of their new video for "Coming Like A Hurricane." In addition to The New York Times T Magazine premiere, the video for "Coming Like A Hurricane" which was directed by Dan Elhadad is available to post and share via YouTube. Last week The AV Club ran an exclusive album stream and said, "Fans of Dungen and The Tallest Man On Earth might like Death Has No Dominion...Tracks like "Harvest" and "Poughkeepsie Exit" are emotional and dramatic, telling the story of the band's journey through both aural space and to the Rubber House, a New York building once owned by Willem Dafoe." Wondering Sound described "Coming Like A Hurricane" as, "a stark, chilly acoustic folk number pulled along by soft, ethereal vocals and a drifting, ghostly melody. It's the kind of thing you might hear drifting in the breeze through a forest in the middle of the night - spectral, soothing and ominous at the same time." Death Has No Dominion is available now on CD in the SQE online store and digitally via iTunes.

The story of Death Has No Dominion exists within their music. It is not a story that begins with the phrase "once upon a time" and it does not unfold chronologically. It is implacable, built on atmosphere and emotional heft rather than centered on actual fact. If you listen closely, you can hear it, the tale of two musicians who found an inherent and inspirational connection in the juxtaposition of themselves.

Rasmus Bak and Bjarke Niemann are the two musicians. They have known each other for a certain amount of time. They are both from the same place, but the exact location of that place is not relevant to this story. In the fall, some time ago, the two musicians went to upstate New York to stay in a black house once owned by Willem Dafoe. It is called the Rubber House and among its many strange features is a gigantic dance room. Rasmus and Bjarke drank a lot of wine in the house and they made a lot of music.

On the first night they wrote a song called "Poughkeepsie Exit," a delicate, acoustic number that reveals a moody, intimate vibe. It opened their eyes to what this partnership could yield. They wrote more songs. They were interested in how a pair of ukuleles could manifest a soaring, quietly significant sound so unlike the instrument's usual aesthetic. There are very few preconceived notions about the ukulele. The musicians felt liberated from prescribed ways of playing and creating. There was nothing in their minds except the collaboration founded in each new moment. They were centered on the idea of a new dawn. It is an idea that found its way into everything they made after that. Things were not the same when Rasmus and Bjarke came back from that place.

During some future time, over the course of a certain number of months, the duo met regularly in the studio, writing a new song every time they came together. There were many songs, recorded in Los Angeles, Copenhagen and New York. Some of the songs became an album they named after themselves. The first track, "Harvest," set the tone for what followed, and each song constructed a visceral atmosphere of sound infused with emotive resonance. "Coming Like A Hurricane," a propulsive, ambient number, opened the possibilities of that sound space. Those two numbers, along with "Poughkeepsie Exit," are the key elements of the story.

Death Has No Dominion is a new dawn itself, in some ways. It represents a new means of artistic creation, of going with the flow and accepting whatever emerges. It is about a pureness of energy and an emphasis on the significance simplicity can yield. It is something you can hear in every note that is played, and it is also something that is present in the silent spaces between the notes. That is the story of the band. You must listen to fully understand it. Harvest Track List: 1. Harvest (stream)2. Monkey Island

1. Harvest (stream)2. Monkey Island

3. Reaching The Shore

4. Uproar In Heaven

5. Poughkeepsie Exit

6. May Your House Be Safe From Tigers

7. Coming Like A Hurricane (stream)

8. Out Of Your Mind

9. No Return

10. Daybreak Olympics For more information, please visit: http://deathhasnodominion.com/http://www.sqemusic.com/artist/death-has-no-dominion

Watch: "Coming Like A Hurricane" video via New York Time T Magazine orYouTubeListen: "Coming Like A Hurricane" via Wondering Sound or SoundCloud

Watch: "Coming Like A Hurricane" video via New York Time T Magazine orYouTubeListen: "Coming Like A Hurricane" via Wondering Sound or SoundCloudDanish-duo Death Has No Dominion's self-titled album is out now on SQE. The New York Times T Magazine chatted with the band about the new album, their roles at the Danish clothing brandLibertine-Libertine, and the making of their new video for "Coming Like A Hurricane." In addition to The New York Times T Magazine premiere, the video for "Coming Like A Hurricane" which was directed by Dan Elhadad is available to post and share via YouTube. Last week The AV Club ran an exclusive album stream and said, "Fans of Dungen and The Tallest Man On Earth might like Death Has No Dominion...Tracks like "Harvest" and "Poughkeepsie Exit" are emotional and dramatic, telling the story of the band's journey through both aural space and to the Rubber House, a New York building once owned by Willem Dafoe." Wondering Sound described "Coming Like A Hurricane" as, "a stark, chilly acoustic folk number pulled along by soft, ethereal vocals and a drifting, ghostly melody. It's the kind of thing you might hear drifting in the breeze through a forest in the middle of the night - spectral, soothing and ominous at the same time." Death Has No Dominion is available now on CD in the SQE online store and digitally via iTunes.

The story of Death Has No Dominion exists within their music. It is not a story that begins with the phrase "once upon a time" and it does not unfold chronologically. It is implacable, built on atmosphere and emotional heft rather than centered on actual fact. If you listen closely, you can hear it, the tale of two musicians who found an inherent and inspirational connection in the juxtaposition of themselves.

Rasmus Bak and Bjarke Niemann are the two musicians. They have known each other for a certain amount of time. They are both from the same place, but the exact location of that place is not relevant to this story. In the fall, some time ago, the two musicians went to upstate New York to stay in a black house once owned by Willem Dafoe. It is called the Rubber House and among its many strange features is a gigantic dance room. Rasmus and Bjarke drank a lot of wine in the house and they made a lot of music.

On the first night they wrote a song called "Poughkeepsie Exit," a delicate, acoustic number that reveals a moody, intimate vibe. It opened their eyes to what this partnership could yield. They wrote more songs. They were interested in how a pair of ukuleles could manifest a soaring, quietly significant sound so unlike the instrument's usual aesthetic. There are very few preconceived notions about the ukulele. The musicians felt liberated from prescribed ways of playing and creating. There was nothing in their minds except the collaboration founded in each new moment. They were centered on the idea of a new dawn. It is an idea that found its way into everything they made after that. Things were not the same when Rasmus and Bjarke came back from that place.

During some future time, over the course of a certain number of months, the duo met regularly in the studio, writing a new song every time they came together. There were many songs, recorded in Los Angeles, Copenhagen and New York. Some of the songs became an album they named after themselves. The first track, "Harvest," set the tone for what followed, and each song constructed a visceral atmosphere of sound infused with emotive resonance. "Coming Like A Hurricane," a propulsive, ambient number, opened the possibilities of that sound space. Those two numbers, along with "Poughkeepsie Exit," are the key elements of the story.

Death Has No Dominion is a new dawn itself, in some ways. It represents a new means of artistic creation, of going with the flow and accepting whatever emerges. It is about a pureness of energy and an emphasis on the significance simplicity can yield. It is something you can hear in every note that is played, and it is also something that is present in the silent spaces between the notes. That is the story of the band. You must listen to fully understand it. Harvest Track List:

1. Harvest (stream)2. Monkey Island

1. Harvest (stream)2. Monkey Island3. Reaching The Shore

4. Uproar In Heaven

5. Poughkeepsie Exit

6. May Your House Be Safe From Tigers

7. Coming Like A Hurricane (stream)

8. Out Of Your Mind

9. No Return

10. Daybreak Olympics For more information, please visit: http://deathhasnodominion.com/http://www.sqemusic.com/artist/death-has-no-dominion

Published on June 23, 2014 10:37

This Will Destroy You Announce Album, Out 9/16

THIS WILL DESTROY YOU ANNOUNCE ALBUMANOTHER LANGUAGE, OUT 9/16 ON SUICIDE SQUEEZE RECORDS, PREMIERE TRACK "DUSTISM," US TOUR BEGINS IN OCTOBER

Photo Credit: Karlo X Ramos

Photo Credit: Karlo X Ramos

Listen to track "Dustism" via Stereogum

Since 2004, This Will Destroy You has been forging some of the world's most brutal, dynamic, and precariously visceral instrumental rock. In addition to a vigorous tour schedule, their celebrated discography and critically renowned soundtrack work for feature films and documentaries have earned them a sizable and fervent international following. Another Language, TWDY's fourth full length LP, marks their euphonious return from a prolonged vacuous dark period that threatened to break both the band and the members themselves. Rather than be stifled by their experience TWDY were atomized and subsequently made anew, emerging with a revived energy and reinforced sense of solidarity. As a result, Another Language captures the band at its most potent, honed, and utterly powerful form yet, displaying an edified unity and graduated sense of song-writing, tonal complexity, and studio prowess.

TWDY's new found clarity of vision would come after a state of near dissolution that ensued after the massive success of their 2006 debut Young Mountain and 2008's eponymous follow up. Personal struggles, growing pains, the loss of band members, and a series of close, untimely tragedies set the tone for what would be the band's darkest and most introspective album yet, 2011's Tunnel Blanket. The following two years stress tested the band to the point of ruin; consecutive continent-hopping tours as well as the pressures of matching their previous two albums' accomplishments took a nearly unbearable toll. TWDY's spirits were lifted when both independent filmmakers and Hollywood began to eye their discography for prominent placement in several critically acclaimed films, including the Oscar-winning Moneyball. The arrival of 2013's Live in Reykjavik triple LP was warmly received by fans and critics alike, further rejuvenating the band after years of relentless, grinding tours. In October of 2013 TWDY returned to Elmwood Recording, once again working with engineer John Congleton, fully prepared to construct their next work from the inside out.

From the opening moments of Another Language it is clear that the band has achieved its aim. The reflective opening dialogue of guitar, choral-like organ, and shimmering Rhodes on New Topia float over nuanced warbling swells of tape before being completely disintegrated by a shock wave of blistering guitars, bass, and locomotive poly-rhythms. These peaks and valleys of emotive dynamism are expertly guided by the dexterous drum work of Alex Bhore, who offers up droves of ghost-notes and compounded cadences that energize the album with a fully realized freedom of movement. The band's frequency spectrum now extends to new heights via adornments of tubular bells, microcassette manipulations, and washes of tuned feedback by guitarists Christopher King and Jeremy Galindo while bassist Donovan Jones ensures that the band's roots dig deep into the netherworld of sub-frequencies. An earthy realism can be heard throughout Another Language's nine tracks, as if all of its sound sources have been so heavily disguised under layers signal manipulation that their original form is weathered beyond recognition. Composition duties were shared equally more than ever, offering TWDY an opportunity to delve deeper into the writing process with an unprecedented level of cohesion.

Forced to redefine themselves as individuals, artists, and as a unit, TWDY's Another Language exudes a corporeal sense of the formidable journey, which was overcome in order to arrive at their newly galvanized state of confidence and artistry.

This Will Destroy You is Jeremy Galindo, Christopher King, Donovan Jones, and Alex Bhore. "Another Language" recorded by John Congleton, Alex Bhore, and Christopher King. Mixed by John Congleton except "The Puritain" mixed by Christopher King and Jeremy Galindo. Mastered by Alan Douches. Strings by Jonathan Slade. Art by Land.

* * *

Another Language Tracklisting /

01. New Topia02. Dustism03. Serpent Mound04. War Prayer05. The Puritan06. Mother Opiate07. Invitation08. Memory Loss09. God's Teeth

Tour Dates /

10.21.14 - The Kessler Theater - Dallas, TX *10.22.14 - Fitzgerald's - Houston, TX *^10.23.14 - The Opolis - Norman, OK *^10.24.14 - Firebird - St. Louis, MO *^10.25.14 - Lincoln Hall - Chicago, IL *^10.26.14 - Pyramid Scheme - Grand Rapids, MI *^10.27.14 - Grog Shop - Cleveland, OH *^10.28.14 - Lee's Palace - Toronto, ON *^10.29.14 - Tralf - Buffalo, NY *^10.30.14 - Brighton Music Hall - Allston, MA *^10.31.14 - The Bowery Ballroom - New York, NY *^11.01.14 - First Unitarian Church - Philadelphia, PA *^11.02.14 - U Street Music Hall - Washington, DC *^11.03.14 - Cat's Cradle - Carrboro, NC *^11.04.14 - The Masquerade - Hell - Atlanta, GA *^11.05.14 - Workplay Theater - Birmingham, AL *^11.06.14 - One Eyed Jacks - New Orleans, LA *^11.09.14 - Fun Fun Fun Fest - Austin, TX

* w/ Future Death^ w/ Silent Land Time Machine

Links / This Will Destroy You on Facebook This Will Destroy You on TumblrFollow This Will Destroy You on InstagramSuicide Records

Photo Credit: Karlo X Ramos

Photo Credit: Karlo X RamosListen to track "Dustism" via Stereogum

Since 2004, This Will Destroy You has been forging some of the world's most brutal, dynamic, and precariously visceral instrumental rock. In addition to a vigorous tour schedule, their celebrated discography and critically renowned soundtrack work for feature films and documentaries have earned them a sizable and fervent international following. Another Language, TWDY's fourth full length LP, marks their euphonious return from a prolonged vacuous dark period that threatened to break both the band and the members themselves. Rather than be stifled by their experience TWDY were atomized and subsequently made anew, emerging with a revived energy and reinforced sense of solidarity. As a result, Another Language captures the band at its most potent, honed, and utterly powerful form yet, displaying an edified unity and graduated sense of song-writing, tonal complexity, and studio prowess.

TWDY's new found clarity of vision would come after a state of near dissolution that ensued after the massive success of their 2006 debut Young Mountain and 2008's eponymous follow up. Personal struggles, growing pains, the loss of band members, and a series of close, untimely tragedies set the tone for what would be the band's darkest and most introspective album yet, 2011's Tunnel Blanket. The following two years stress tested the band to the point of ruin; consecutive continent-hopping tours as well as the pressures of matching their previous two albums' accomplishments took a nearly unbearable toll. TWDY's spirits were lifted when both independent filmmakers and Hollywood began to eye their discography for prominent placement in several critically acclaimed films, including the Oscar-winning Moneyball. The arrival of 2013's Live in Reykjavik triple LP was warmly received by fans and critics alike, further rejuvenating the band after years of relentless, grinding tours. In October of 2013 TWDY returned to Elmwood Recording, once again working with engineer John Congleton, fully prepared to construct their next work from the inside out.

From the opening moments of Another Language it is clear that the band has achieved its aim. The reflective opening dialogue of guitar, choral-like organ, and shimmering Rhodes on New Topia float over nuanced warbling swells of tape before being completely disintegrated by a shock wave of blistering guitars, bass, and locomotive poly-rhythms. These peaks and valleys of emotive dynamism are expertly guided by the dexterous drum work of Alex Bhore, who offers up droves of ghost-notes and compounded cadences that energize the album with a fully realized freedom of movement. The band's frequency spectrum now extends to new heights via adornments of tubular bells, microcassette manipulations, and washes of tuned feedback by guitarists Christopher King and Jeremy Galindo while bassist Donovan Jones ensures that the band's roots dig deep into the netherworld of sub-frequencies. An earthy realism can be heard throughout Another Language's nine tracks, as if all of its sound sources have been so heavily disguised under layers signal manipulation that their original form is weathered beyond recognition. Composition duties were shared equally more than ever, offering TWDY an opportunity to delve deeper into the writing process with an unprecedented level of cohesion.

Forced to redefine themselves as individuals, artists, and as a unit, TWDY's Another Language exudes a corporeal sense of the formidable journey, which was overcome in order to arrive at their newly galvanized state of confidence and artistry.

This Will Destroy You is Jeremy Galindo, Christopher King, Donovan Jones, and Alex Bhore. "Another Language" recorded by John Congleton, Alex Bhore, and Christopher King. Mixed by John Congleton except "The Puritain" mixed by Christopher King and Jeremy Galindo. Mastered by Alan Douches. Strings by Jonathan Slade. Art by Land.

* * *

Another Language Tracklisting /

01. New Topia02. Dustism03. Serpent Mound04. War Prayer05. The Puritan06. Mother Opiate07. Invitation08. Memory Loss09. God's Teeth

Tour Dates /

10.21.14 - The Kessler Theater - Dallas, TX *10.22.14 - Fitzgerald's - Houston, TX *^10.23.14 - The Opolis - Norman, OK *^10.24.14 - Firebird - St. Louis, MO *^10.25.14 - Lincoln Hall - Chicago, IL *^10.26.14 - Pyramid Scheme - Grand Rapids, MI *^10.27.14 - Grog Shop - Cleveland, OH *^10.28.14 - Lee's Palace - Toronto, ON *^10.29.14 - Tralf - Buffalo, NY *^10.30.14 - Brighton Music Hall - Allston, MA *^10.31.14 - The Bowery Ballroom - New York, NY *^11.01.14 - First Unitarian Church - Philadelphia, PA *^11.02.14 - U Street Music Hall - Washington, DC *^11.03.14 - Cat's Cradle - Carrboro, NC *^11.04.14 - The Masquerade - Hell - Atlanta, GA *^11.05.14 - Workplay Theater - Birmingham, AL *^11.06.14 - One Eyed Jacks - New Orleans, LA *^11.09.14 - Fun Fun Fun Fest - Austin, TX

* w/ Future Death^ w/ Silent Land Time Machine

Links / This Will Destroy You on Facebook This Will Destroy You on TumblrFollow This Will Destroy You on InstagramSuicide Records

Published on June 23, 2014 10:33

June 21, 2014

Julian Rios Interview

Julian Rios Interview

Spanish author Julian Rios, who lives in Paris, was in New York recently, and we spent some time together. He is the author of several books including Larva, Poundemonium, and the new one is Loves That Bind. He also wrote two books with Octavio Paz, including Solo For Two Voices. Paz had just passed away a few weeks before we spoke. They had actually been writing some new work in the past year. Rios sees writing from Spain and Latin America as being of the same root. He has been a favorite author of mine for years, ever since I read Larva and some shorter works published in magazines.

It was my pleasure to finally meet him on the occasion of his newly translated novel, Loves That Bind.

by Alexander Laurence

AL: I just got back from London yesterday, and I realized while I was there that I was going to talk to you soon. Several of your books take place in London, and although you're Spanish, and have lived in Spain and Paris most of your life, you write often about being in London. Why is that the setting of some many of your novels?

Julian Rios: London is a kind of resume of the universe. New York is also. It happens that I knew London very well and it was a city that I liked. For me, the London that I like is not the "Anglo-Saxon" London, but, as I say, the resume of the universe, a kind of melting pot of different languages and different cultures. Different types of people have been established in London for many years, and they created their own cultures, whether it's the Italians, the Chinese, the Indians, the Pakistanis, etc. That adds up to a fascinating concentration of cultures.

AL: You are interested in the literary history of London too....

JR: I am interested in the mythical side of London because it is a mythical city. It's like how T. S. Eliot calls it "unreal city." It's more real than reality. You have the real city and the mythical side of the city that exists in novels. For me, in many of my novels, the important side is the London seen from a foreign point of view. If somebody is a foreigner, he feels at home with other foreigners, because nobody belongs to London and everybody is a foreigner in a sense. That is the question. In Loves That Bind for example, each day the narrator takes a different path in London trying to chase or to find his lover. Each part of London connects in a way with different views, experiences, remembrances, past loves, and literary allusions. There are many things there.

AL: Is the character Emil the same person as the other books?

JR: He comes from Larva and Poundemonium. He's the same character. He's called Milliaus: a thousand aliases. That's his name in Spanish. It belongs to the same cycle and different parts of my book, or multi-novel, if you want. In Larva, the language was more important; in Poundemonium, the life of Erza Pound and literary history; and in Loves That Bind, the characters are most important. I have just finished a new novel, Monsturary, where the characters are equally important.

AL: I noticed that you are interested in puns and multi-lingual words. Does that come from the influence of James Joyce and Arno Schmidt, or is it that you are a Spanish person living in several countries and fluent in several languages?

JR: Maybe it's not the Castillian but the Out-Castillian in me. I am a kind of an "Out-Cast." I'm outside my own country. I am from the Northwest of Spain. Galicia is a Celtic land. There's a situation in the world now where everyone is sort of a displaced person. If you go to an airport in any part of the world, you have the global village there, the immigration, and everybody is moving, even if you have your own roots to some land or culture. The world is moving into that direction which is the direction of uncertain situations. We don't have any fixed point of view anymore. In my novels I choose London as a setting, because I like the idea of a labyrinth as a city. I found in that situation, when you have foreigners with other foreigners, you are home without a home. You can't go home again. There's no home anymore, or every part is a provisional home.

AL: With Larva there was this sense of a multi-novel, that it doesn't end with a book. Can you explain your sense of novel? I know that I have spent much time reading Maurice Roche's work, especially CodeX, and I'm surprised that he even links the word "novel" to it because it destroys all the conceptions of a regular novel.

JR: You think of characters and plot. I am against this kind of experimentation. I always insist on a double-track. In the circus it's like riding two horses at the same time. Of course you are a writer and you're writing, you're not filming, then you use words. For me, the use of words is very important. I need the sensuality of the word. I want the word to have flesh. One of my books is called The Sensual Life of Words. At the same time when I write a novel I am telling a story. I don't like books that are only interested in a verbal pyrotechnics and flashes without content. Plot, characters, and telling a story are very important to me. In Loves That Bind, you will follow a real story about love, and a sad one I think. Some people read intellectual things but a novel is also a notation of the heart. A recent reviewer said that I was part of a generation of new novelists born after Franco, and Franco doesn't appear in the novels. In Loves That Bindthere are four or five concrete allusions to Franco. The time of the novel, 1973, Franco was still around. I am not writing from a stratospheric situation. I am definitely connected to my times and everything that matters in political and individual terms.

AL: Since you are known for writing Larva, people see you as a forerunner to the hypertext. It is a very difficult book to read.

JR: Larva has many sides. If you read the last part of the book which is made up of notes, meta-narratives, that's only one part. Larva is a very complex work, and maybe it is a premonition of experiences we have now. We cannot control everything when you use computers. Larva was written before the computer age, but the first Spanish readers had the sensation of a computer work: that you could open windows and go there, and go backwards. That means a new approach to reading. Hypertext is always in the text. The texts of Joyce and the other great authors are really hypertexts. You can really open windows infinitely.

AL: Is the new novel, Loves That Bind, a simpler approach to writing?

JR: The structure, at first glance, is much more traditional. Each chapter consists of one day. The book takes place in one month. The setting is London in 1973. I learned something on this novel: I learned to seem simple when I am much more complicated. I want to seem accessible to everybody, so they can understand, and at the same time, I want to disguise the difficulties on the surface. I am very happy with that. If you want to stay on the surface and come away with an impression. The majority of the readers will read it one time and get an idea and an experience, but if you have more time you can see things that you didn't see things the first time. It's important for a book to have real readers. I found it important to have a sensuality in writing and communicate that, and also to keep in mind that reading is an intellectual activity. Everybody tries to seduce the reader. I was reading a review today and the critic was embracing the novel and comparing it to Tarantino and Pulp Fiction. For me, a novel which is the equivalent of Tarantino means it is the opposite of a real novel. A novel should convey an experience so different from cinema. The problem is writers trying to tell stories like filmmakers.

AL: Some younger readers are more influenced by visual media. They like film and pop culture and music and TV and can relate to that instead of Modernist literature.

JR: Zamyatin, the Russian novelist said "The future of the Russian literature is in its past." That seems to be against progress. I understand that the century is almost over and we are leaving the 20th century. Look backwards and see how many beautiful novels this century has produced. You have Nabokov, Joyce, and Proust. Many critics think that the 19th century was the big century of the novel. The 20th century produced many great writers if you look back. Right now we have many programs, many publications, but not many good writers. Writing needs time. Publishers are pressuring their authors: "Give me your next novel!" Many writers are producing like copycats. Writing needs time for maturation and style. No new author needs to remake Ulysses. But they need to take the moral example of those writers who did things with dedication and time and hard work and emotion. This time, the fin de siecle, is very characteristic, and the same as the last one. Very simple naturalistic novels were produced, and so were realistic works without ambition. Every work was conservative and conformist. I think that will be the end of the century.

AL: Have you been writing for a long time?

JR: Maybe too young. When I was a child I wrote poems and I wanted to be a writer. But the important thing for me is to work against facility. I used to be an easy-writing person. I soon learned a writer is not only a person who writes something but a person who doesn't write certain things. That is very important, because everybody has these great or fantastic ideas. We have to realize that a writer is someone who refuses to write some things.

Published on June 21, 2014 17:57

Harry Mathews Interview

An Interview with Harry Mathewsby Alexander Laurence

Alexander Laurence: You have spent most of your life in Europe, mostly in Paris and in France, and a few years in Spain and Italy too. Paris has been your real base since 1952. Do you think about the United States a lot, and the fact that you are an American living abroad? Do you think about your “American-ness?”

Harry Mathews: I do not think that I expected to become anything else besides an American. I did, I think, have some misguided expectations about changing my spots and fitting into the European communities where I have lived. After stubbing my toes trying to do that, I gave it up, and accepted the fact that I’ll always be an American wherever I live, and no matter how well I know the language. I very much enjoy the life that I have lived in Europe. I enjoy equally being an American, more and more so. I had really no problem with America except in the very beginning when I didn’t know much about it. I thought Amerca was the milieu that I had grown up in, which was just a tiny part of it. I started coming back to America in the late fifties. I visited the West Coast several times, the South a little bit, and Texas, of which I’m particularly fond. I enjoy very much having two places to live, to feel that I could live happily in either Europe or America, to be at home in either place. But I have no illusions;I have no desire to be anything but an American. It’s not something that I think about except in terms of language. In that respect, living abroad is useful. When you’re living in a country and you’re surrounded by people that are not speaking your language, and especially in my case, where your wife and your step-children are all speaking in a foreign langauge, you’re obliged to become aware day after day of what your langauge is.

AL: You never thought of writing a novel directly in French?

HM: No. I’ve written shorter things, at most three or four pages. That will be about it because it’s only rarely that what I want to do when I write will correspond to my limitations in French. Learning written French proficiently as an adult takes a lot of work, and although it has been done by a few people, they still have a different relationship to the language than someone who has grown up speaking that language. Those people will never write French as well as someone who has gone to school and high school in France.

AL: Why do you suppose that is?

HM: That’s a good question. I would suggest that the answer is this: one’s relatioship to the language is a dramatic and possibly traumatic one. The experience of learning to read and write, first in terms of just letters and words, then in terms of syntax, is a dramatic and possibly traumatic experience. The writer who has not undergone that kind of drama, which is perhaps only available to people who are between the ages of five and fifteen, will never be able to write as well as someone who has. The theory of language which most appeals to me is one that says the trauma of the absense of the mother’s breast is replaced by words. That is to say the mouth is filled up with words that take place of the breast, beginning with the cry, then articulations of that cry. I think that the teaching of language by the mother to the child, or the family which centers on the mother, is post-traumatic. I think that the trauma has preceded it, and that language can be, on the contrary, a consoling substitute and one that is not alienating. For me, the drama began with finding out that language was not only a link between my body and my parent’s bodies, that in fact the link between me and my family’s surroundings could be alienated by written language. This is just a concept and not a record of what I felt at the time. But something happened then which I think probably happens to other people. There is also the fact that learning is painful.

AL: You are part of the Oulipo. Do you think that if you stayed in New York, there would have been that sort of community available? Paris has a history of groups, literary movements,and communities.

HM: I had a group in New York long before the Oulipo. The Locus Solus group was my first and most important literary environment.

AL: Which was related to the book that came out in 1971: An Anthology of New York Poets?

HM: Yes. It was the whole New York that I hadn’t known, that I got to know through Kohn Ashbery. I wouldn’t want to limit it to the people who were on or in Locus Solus, because through them I discovered a community that I could be a part of any time that I wanted to. I wasn’t here in New York very much, so I wasn’t a working member of the so-called New York School. But I was an honorary member. It was something that I knew that I could count on for support and acceptance. The Oulipo plays a very different role. First of all, it’s not a writing group.

AL: You meet once a month?

HM: Sure. It’s great. It’s wonderful. It’s a sort of a family, no doubt about it. It makes living in Paris much easier.

AL: Do you think that such a group like the Oulipo, could have been in New York or San Francisco?

HM: Well, in San Francisco you have the Language Poets, but again, that’s a writing movement. The Oulipo is not a writing movement.

AL: I was thinking of a group or a community that consciously creates an association of ideas. It seems that in the past American writers have worked independently, but in retrospect, they are thrown together in groups or movements by critics.

HM: That’s true in France as well, and it’s certainly true of the writers in the Oulipo. We don’t work together as writers at all. You’re right that it is a group, you’re right that it’s a nice substitute family to belong to, but it’s not a group of writers. In fact, many members are not writers. And those who are writers write in many different ways. We do not necessarily agree with each other about each other’s writing. What we share is an interest in exploring the possibilities of constrictive forms. People in San Francisco, like the Langiuage Poets, Carla Harryman and Richard Silliman for instance, discuss each other’s work; and that’s fine. Theirs is a real literary movement. It’s like Braque and Picasso trying things out with each other and testing their ideas. On the other hand, the Nouveau Roman, for all its fame, was not a true literary group or movement. It was a publishing gimmick, one that worked.

AL: When did you first meet Raymond Queneau, and when did you first become aware of his work?

HM: I first became aware of his work in 1956. That was before the Oulipo existed. I admired him and actually met him and read many of his books before my or even his Oulipo days. I heard of the Oulipo in 1968. It didn’t interest me at all. I didn’t know what was going on because the people who told me about it, as most people do, got it wrong and presented it in an inaccurate way. Later Georges Perec told me more about it and invited me to one of the lunches. That led to my being elected to the group.

AL: So you first met Perec soon afterwards?

HM: I met Perec in 1970.

AL: How did you meet him? Do you remember?

HM: Yes, I remember very well. My first novel, The Conversions, was about to come out in French, and I had left some proofs with a friend who gave them to an editor who worked with Georges Perec’s publishers, and she gave them to him. He wrote me an enthusiastic letter, and I wrote him back. Then we called each other up and met for drinks one afternoon.

AL: What did you think of Perec’s writing?

HM: When I met Perec, I hadn’t read anything by him. After we became friends I read his books as they came out. I thought of him primarily as a friend: I was interested in his books because they were his. I was neither surprised nor not surprised when he wrote La Vie Mode D’Emploi.

AL: You were elected to the Oulipo in 1973, the same year as Italo Calvino. How did this happen?

HM: What happens is there are guests of honor who may or may not become members of the Oulipo. I went there and we got along fine. (They used to have lunches, now we have dinners.) I talked a litle about my work.

AL: Did they know you at the time?

HM: Some of them did. Queneau did. Most didn’t. I do know that I went and had a good time, and they seemed to enjoy my company. Later I received a letter that told me I had been elected as a member to the Oulipo. There was no ceremony. It was totally informal.

AL: Did you feel that being elected was a transformation for you, that you and your writing changed somehow, or was the change not significant at all?

HM: I was very pleased. It was marvelous to be elected to this group and being accpeted by them. I got involved little by little, and learned more about their ideas. I didn’t know much about them, about the theoretical aspect of it. I had done Oulipian things on my own, but I hadn't thought in general terms about constrictive form. In fact, I guess that you're right to ask that question because one big difference it made was reassuring me about what seemed to be almost an aberration in having written this way. I hadn't known anything about Oulipian procedures. So what before I had felt uneasy about now was given a blessing. That was very comforting.

AL: Could you talk about some of the recent Oulipian activity? What have you done as a group and not individually?

HM: The work inside the group has led to publications of specifically Oulipian research. Two volumes published by Gallimard, and a whole series of smaller pamphlets which were eventually collected. A third volume of them will be out fairly soon. That's one ongoing part of our activity. Then there are the uses to which individual writers put the Oulipian idea such as Perec, Calvino, myself, Jacques Roubaud, Queneau, and so forth. What happens in the Oulipo is we invent or rediscover or analyze constrictive forms. The books happen outside, independently. The books are our own business as individual writers.

AL: So when you write a new novel, does it ever happen that someone like Jacques Roubaud will come up to you and say how he admires your work?

HM: Never. At a meeting of the Oulipo, we might say, in parenthesis, to one another "You've written a masterpiece." But we never discuss each other's work except in its explicitly Oulipian aspects. That's not the point. The Oulipo is not about written works. It's about procedures.

AL: Is it about production?

HM: It's about structure and procedure. Production in the sense of potential production, but not the product. I can give you an example of what happens which is much more interesting for all of us. I've just started a novel last month, and at the last meeting I presented one of the structures that's going into the novel and explained how it will work. But that has nothing to do with what the book is going to be like as a whole, or whether it will be good or bad. I'm glad you asked that because it's important to get that clear.

AL: One way the Oulipo has progressed is that it has invented some structural ideas, and then essays about them have been collected into a volume.

HM: We have ideas all the time! We have both practical ideas and theoretical ideas. I'm strong in the practical realm. I mean that I'm good at devising things to do. Jacques Roubaud is not only good at devising things to do, he's also a meticulous theoretician. He's very good at defining and working out the theoretical consequences of the general thinking that's going on.

AL: Are there some structural ideas that do not get carried out?

HM: That's not the point. The point is not the carrying out, but developing the structure. The only carryings out that are important are what we call "record setting." That's what Georges Perec did with the palindrome and the lipogram. He demonstrated that you could write a very long, beautiful palindrome. This had never been done before. He also demonstrated that you could write an extraordinary interesting, entertaining, and fascinating novel without using the letter e. That had never been done before. In that sense, those are actual Oulipian acts because they demonstrate an unrevealed potentiality of a form like the palindrome. There are many natural palindromes. There's no big deal about a palindromic word, for instance. But to do what he did is a true Oulipian activity. Perec demonstrated that the palindrome exists as an extensive form.

AL: What are the meetings of the Oulipo like Today? Can you describe one to me?

HM: Sure. They all resemble each other very much. There's one on November 16, 1989. A dinner. We'll go to Paul Fournel's, a very good writer, who also runs a publishing house in Paris. He and his wife will welcome us at seven o'clock, and we'll have drinks for an hour or so, then have dinner together. We'll work through the evening. We have an invariable sequence of categories that we work through: first comes "creation," then "erudition," "action," and "lesser proposals," which is a sort of odds and ends. At the beginning of the meal, one of us is picked to preside over the meeting, and someone else picked to be the secretary takes notes on it. We are initially asked if we have contributions to make. If I have something to say in the category of "creation" I'll say "yes, I do." After a few minutes, we have a schedule for the evening. The meetings end about ten-thirty or eleven. There is a slight tendency to rowdiness as the hours pass.

AL: So, each meeting ends with a good feeling?

HM: Yes, usually.

AL: Or is there a lot of arguing?

HM: Oh, sometimes there is some violent arguing, but the argument is mostly about getting definitions accurate. Sometimes there will be a procedure that is presented which may or may not be Oulipian, and the discussion or argument will be "Is this Oulipian?" Does it correspond to Oulipian principles: if not, why not? If so, why? So there can be some lively discussion. Rarely does someone leave in a state of upset.

AL: Your fourth and latest novel, Cigarettes, was popular? Or not?

HM: It was more popular than the others. It certainly didn't get to a lot of readers.

AL: It was translated into French soon after its publication here, in the States, in late 1987. When did you start this novel, and when did you finish it?

HM: Ah, that took me forever to write. I think that I began it in 1978, and it took me eight or nine years to write it all. A lot was going on at the time. I did work on it more or less continuously. It was very hard formally to handle, and I gave myself a lot of strict rules. I was doing things that I had never done before. That was one of the rules: not to do anything I had done before.

AL: To me at least, one of things that I noticed about Cigarettes is that it seems like was written by a female writer, if you don't look at the cover. Surely the texture of the language is more feminine.

HM: Oh, that's nice to hear. I agree with that. I hope it's true.

AL: Female writers, especially female writers who write popular or romance novels, usually write in forms familiar to everyone though.

HM: The form of Cigarettes isn't familiar to anyone, but the language is. Although a lot of people found it difficult. I was astounded at the number of people. To me, it was utterly transparent. Many people found it difficult, especially the beginning, and that totally baffled me.

AL: Yes, I think that I had some difficulty with the first part of the book originally. But soon as I became more accustomed to the book, it became more fascinating as it unfolded. It worked. I think that the reader must rely on memory more with this book than with others.

HM: But that applies to any detective novel, sometimes far more so.

AL: Your most recent books, 20 Lines A Day and The Orchard, are much different. One is a journal and the other is a memoir. Can you talk about how these works came about.

HM: They were very important to me, as was The Armenian Papers, all three. 20 Lines A Day and The Armenian Papers were written without any idea of what was going to happen. They were written off the top of my head. It was a surprise to me how they came out. Jacques Roubaud said that after working as an Oulipian for twenty years, my instincts were geared to intuitive forms. Or at least I had enough intuitive formal sense to be able to wing it without a structural procedure in mind. I was interested in 20 Lines A Day particularly, because of the processes expressed in that book. I don't mean formal processes or writing processes, but the psychological process of writing each day. That was something that I didn't know. That seems to be what the book is about. It is coming to terms with myself when faced with a blank page each day.

AL: Other than that process, is it that you don't like to repeat yourself in following the same approach to writing, and if so, is it due to boredom that you avoid writerly habit?

HM: Every book is different in the way it is written. I do not think it's a question of being bored. I think I’m drawn to trying different things.

AL: I wanted you to comment on the phrase "The wealthy amateur," the first words ofThe Conversions.

HM: Grent Wayl.

AL: And this phrase also shows up in Perec's book.

HM: About Bartlebooth?

AL: Yes. And another character. He is described this way. I'm not sure that I understand this phrase. It sounds like something out of a novel by Jules Verne. Is there some special significance behind it?

HM: No. Grent Wayl is like the protagonist in Impressions of Africa. He's like the people in the novels of Raymond Roussel generally. He's like Roussel himself. Roussel as a writer was really an amateur. He was an amateur in other fields. I don't understand the question. The opening of The Conversions is a very loaded sentence. There isn't an explanation. There's no hidden meaning.

AL: I thought that there was a problem here, that this phrase was some known designation of the past.

HM: It's sort of like a 19th century figure. There's nothing realistic about it, in The Conversions

AL: The Way Home is a book published by The Grenfell Press (Leslie Miller). You collaborated on this book with the artist, Trevor Winkfield. Your short story is there next to photoengravings by Winkfield. More and more recently I have seen these editions coming out with artists and writers collaborating.

HM: They have been doing this for a long time. It's become profitable now. Speculators have now entered the market, so there is a market for it. More than there was at one time, thirty years ago. Then, even poets like John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and Frank O'Hara were doing books with painters.

AL: What is an average day like for you now?

HM: I get up around eight, and have breakfast. I usually read part of The Economist, or if I've finished that, I usually read part of a book of contemporary history. I work from about nine till one in the afternoon, till lunch. That is my goal. And after lunch, I may work again. There's usually a lot of things that arrive in the mail that need attending to. This week I've been spending an half an hour in the afternoon proofreading the copyedited text of a bunch of critical essays. There are things like that. I schedule myself, but I don't always keep to the schedule. That is the only way I get anything done. When the work is all done I usually play the piano for an hour. It's fun and games from then on. In Paris, I'm usually with my wife. We talk, read, or go out. It depends. It's the social part of the day. My days are pretty much alone, except for lunch with Marie.

AL: So you've been married to Marie Chaix, also a writer, for quitea while now.

HM: For thirteen years.

AL: And she stays in Paris when you come to New York?

HM: She comes with me when she can, but she has a daughter who is still in high school.

AL: You have a new novel on the way?

HM: It's called The Journalist. Immeasurable Distances, a book of critical essays will come out in December 1991, published by The Lapis Press.

November 1989

Published on June 21, 2014 17:55

Martin Amis Interview

Interview with MARTIN AMISby Alexander Laurence

I looked forward to talking with Martin Amis, British novelist, and author of the new book, THE INFORMATION (Harmony). He is the author of numerous books, including Money, London Fields, The Rachel Papers, Time's Arrow. Like many, we had read many of the articles in The New Yorker and Vanity Fair. The media circus was like as if Kato Kaelin wrote the next Ulysses. Amis complained about being misquoted in The Chronicle, an article which came out the morning we interviewed him. He called the article sloppy and atrocious. Amis pointed out that the writer had misquoted him as saying "desperation" instead of "desertion;" while he drank a "Virgin mary" not a "Bloody mary." He ordered another one while we talked to him in a hotel around Union Square about his new novel. Much hoopla had already been made about his large advance, his new set of teeth, his mid-life crisis, his divorce, but we focused on the art of fiction.

Do you do e-mail?

Martin Amis: I went on-line yesterday on the internet and answered some questions and typed up some answers. It was weird because I don't use a computer as I said when they asked me how I worked. I said "I work in a velvet smoking jacket and write with an ostrich quill." It's not quite the truth.

Good to hear it. In the spirit of Ronald Firbank....

MA: Exactly.

Have you gotten many writers asking you for advice?

MA: You get a little of that. Some advice or encouragement. If someone is struggling with their first book, the only advice I would give them is "Just get to the end, then worry. But do finish it." Then you'll know what you have in front of you. Don't worry about the little decisions along the way.

You didn't worry too much with your first novel The Rachel Papers?

MA: No. Also because I was the son of a writer, ther was never any question of its getting published. I guessed. Simply out of mercenary curiosity most publishers would have taken it. Children of writers are usually good for one or two books, and that's it. There's a curiosity about book number one, rather less for book number two, and then you shut up. That's been the pattern. I'm still at it. I think that some people do think that I've inherited a full set of writer's genes, and that I lie on a hammock drawling into a type recorder, but it's just so easy for me.

I was wondering how you were affected by being around an author growing up, your father, Kingsley: how has that influenced you?

MA: What it does is it de-glamourize the job, because nothing is more banal than what your dad does for a living. I'm the same as all writers but I'm different in that way. I can get off the train of these thoughts of being a writer. I can just let them run on, and not take them too seriously. I'm detached about it. But say you're dad was an army man like Ian McEwan; it seems like a big achievement to write books. But with me, it doesn't seem like an achievement or an oddity. So when I get a bad review I don't lie on the sofa in the fetal position all day.

In The Information there are two types of novelists: there's Gwyn Barry who writes effortlessly like you did with Rachel Papers, which you wrote so young; and there's Richard Tull who writes compendiums of knowledge which don't interest anyone. Do you think that these writers are not so much based on other people so much as them being a struggle between two sides of yourself?

MA: Yes, expect that Gwyn Barry writes crap effortlessly. Neither one of them is me. Many writers would just have one writer as the main character, then there would have been a been a subtle psychological conflict in a writer's mind, but I'm a broad and comic writer, so I get the two and force them apart. Gywn is a compenium of all stupid and vein thoughts you get when you're feeling pleased with yourself and smug, and when you feel slightly over-rewarded. Tied up with that too is the idea that this worldly success is irrevevant, and no big advance, no prize , no sash, no yarn is going to tell you what you want to know: are you going to last after you're dead? It's locked in. You're never going to know the answer.

Richard Tull is obsessed with the idea of immortality: reaching a vast audience, getting good reviews, and it's somehow going to redeem him, that he's considered in the same light as Homer, Dante, Shakespeare....

MA: That's right. Funny enough, as a subject, it's failure that is rich and complex, and poignant. Success is a drag as a subject: it's what Jackie Collins writes about. Success is for the soaps. Failure is what's interesting. Failure is where we live. On the whole, we don't walk around gloating over our little triumphs. We walk around aching about our defeats and disappontments, and since the writer's ego is infinite, there's always some damn thing you're not getting. Even if you won the Nobel prize, you'd be thinking, well, I didn't win it last year and I'm not going to win it next year.

So you think that they're going to give you the Nobel this year for this book?

MA: Yeah. But it matters and it doesn't matter. I read in L. A. at a place called Book Soup, partly a restaurant, and then I ate there at the bar, so I could smoke while I ate. I looked down the bar and there were ten people, and eight to nine of them had my book in front of them. They were chatting and having drinks. I thought "This is the way the world is supposed to be." I want to go to any bar in the world and have people with my book. You want everyone to read you and no one else, basically.

Do you think that since this is a book about two novelists that it's self-conscious or Post-modern?

MA: It isn't really. I've written things that are more Post-modern than this. The fact that it's about writers takes care of that kind of tricky-ness. There's no messing around with the narrative, there's no levels of reality or unreliable narrators. Although the publication of the book has come surrounded by all these Post-modern ironies.

Is it a third person narration? I thought that there was an "I" repeated a few times subtly through the book. Who is this narrator?

MA: There's an "I" in the first sentence. The narrator is me but he disappears halfway through the book. I wondered about that: I think that I wanted to tell the reader where I was coming from. It is a book about mid-life, and for me the mid-crisis came in the form of blanket ignorance, I felt. I just didn't know anything about the world. Milan Kundera said that "We're children all our lives because we have to learn a new set of rules every ten years." Which is a good remark. But I think that the real new set of rules is when you hit forty. All of what you knew up till then is of no use, and you have to start from scratch. I felt that I had to open up to the reader about that and say "How can I be an omniscent narrator when I don't know anything." Which is what it felt like.

Perhaps, besides the mid-life, was this novel trying to track down a modern consciousness in sme way?

MA: Like Richard Tull thinks he's going to do. This novel is a "cri de coeur" rather than a way of indirection like some Post-modern novels. This is direct and straight me. As I say in this book, I think that most books are written in a language thirty years out of date, a generation out of date. The rhythms of thought that are actually out there don't correspond. We write in a kind of pedagogic code. Maybe writing does lag behind the times. I wanted to suggest the new rhythms of thought which change all the time. I think that the modern consciousness gets more and more to be an ungodly mix. What was Timothy J. McVeigh's consciousness like? He probably sees it as kind of straight, that he has a motive and he knows what he's doing. I guess it's a ragbag of Rambo movies and repressed homosexuality.

Do you think you were criticizing self-obsessiveness or vanity?

MA: Um. We need all this vanity and egotism if you're going to write.

Yeah. You need that to get going, but were you creating a critique of vanity, that this was a contemporary problem?

MA: It's a sad thing, but it's an inevitable thing. Writers are really like everyone else in that department. Although I think that everyone sees a bit of their own egotism in these extreme examples. But what are we going to do about being self-obsessed? Try stopping them. I don't think that they're any more sel-obsessed than they used to be. Some things have changed: the language, the setting, the furniture. One difference is that we're so much more clued up about what we're supposed to be thinking and feeling. I'm sure that people freaked in the middle ages when they had their mid-life crisis at age twenty-five. We know what we're going through.

A classicist would think that since Homer, there's not much new under the sun, and with Modernism, there are different levels and they chop it up a bit differently.

MA: That's all true. Funny you should mention the chop up, the William Burroughs thing, where you chop up a page, throw it up in the air and reassemble it in some different way. Some monk in the 12th century was doing the same thing, "art of the scissors," everything has been tried. There is nothing new. What is new is the background. The observable world changes. The rhythm of thought about the world are always changing, heading in some direction, heading away from innocence. That's all we really know about the world: that it's getting less innocent just by the accumulation of experience.

There's a theme in the book of continuing meaninglessness in the world, that Richard is fighting a losing battle to find meaning or control his existence against what is out there, which is nothing.

MA: Yeah. Nothing is the void we come from and return to. You're dead for a lot longer than you're alive.

What can happen at the end of a mid-life crisis than to discover that?