Andrew Lam's Blog - Posts Tagged "writing"

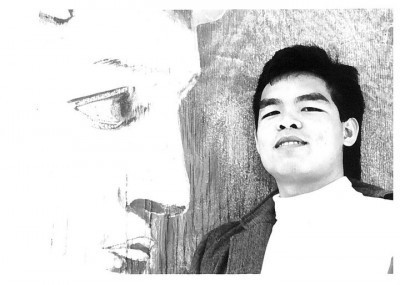

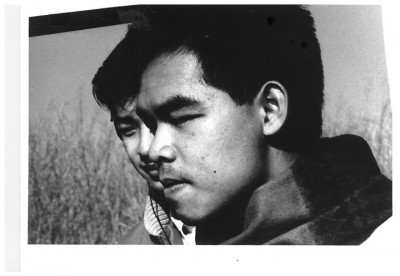

The Education of a Vietnamese-American Writer

When they heard the news, it was as if all the air had been sucked out of the living room. Mother covered her mouth and cried; Father cursed in French. Older brother shook his head and left the room.

I sat silent and defiant. I was only a small child when we fled Vietnam in 1975, but I remember how I trembled then as my small world collapsed around me. I trembled on this day, too, as I told my parents that I was following my passion.

At UC Berkeley, more than half of those in the Vietnamese Students Association, to which I belonged, majored in computer science and electrical engineering. These fields were highly competitive. A few told me they didn’t want to become engineers: some wanted to be artists, or architects, and had ample talent to do so, but their parents were against them. It was worse for those with family still living in impoverished Vietnam. One, in particular, was an “anchor kid” whose family sold everything to buy him perilous passage across the South China Sea on a boatful of refugees. He knew that others were literally dying for the opportunities he had before him, and failure was not an option.

Many of my friends were driven; theirs was an iron will to achieve academic success. On the wall of the dorm room of a Vietnamese friend was his painting of a mandarin dressed in silk brocade and wearing a hat. Flanked by soldiers carrying banners, the young mandarin rides in an ornate carriage while peasants look on and cheer. It was a visual sutra to help him focus on his studies.

And I, with a degree in biochemistry and on a path to attend medical school to the delight of my parents, was, in their eyes, throwing it all away – for what? I had, in secret, applied to and been accepted into the graduate program in creative writing at San Francisco State University. “Andrew, you are not going to medical school,” said Helen, my first writing teacher after reading one of my short stories. My response was entirely lacking in eloquence. “But … but … my mom is going to kill me.”

Filial piety was ingrained in me long before I stepped foot onto American shores. It is in essence the opposite of individualism. “Father’s benefaction is like Mount Everest, Mother’s love like the water from the purest source,” we sang in first grade. If American teenagers long to be free and to find themselves, Vietnamese are taught filial obligation, forever honoring and fulfilling a debt incurred in their name.

My mom didn’t kill me; she wept. It was my father who vented his fury. “I wanted to write, too, you know, when I was young. I studied French poetry and philosophy. But do you think I could feed our family on poems? Can you name one Vietnamese who’s making a living as an American writer? What makes you think you can do it?”

This was the late ‘80s, and the vast majority in our community were first-generation refugees, many of them boat people who had subsisted for years in refugee camps in Southeast Asia.

“I can’t name one,’ I said. “There may not be anyone right now. So, I’ll be the first.”

Father looked at me and with that look I knew he was not expecting an answer; it was not how I talked in the family, which was to say respectfully and with vague compliance. Perhaps for the first time, he was assessing me anew.

I matched his gaze, which both thrilled and terrified me. And crossing that invisible line, failure was no longer an option.

My friend with the painting of a mandarin became an optometrist and gave up art. I remember the first time he showed me the picture of the mandarin, saying “Do trang nguyen ve lang” – Vietnamese for, ‘Mandarin returns home after passing the imperial examination.” But the image needed no explanation, to me or any student from Confucian Asia; it embodied the dream of glorious academic achievement and with it influence and wealth for the entire family. Villages and towns pooled resources and sent their best and brightest to compete at the imperial court, hoping that one of their own would make it to the center of power. Mandarins were selected and ranked according to their performance in the rigorous examinations, which took place every four years.

Vietnam was for a long time a tributary of China and it was governed by mandarins, a meritocracy open to even the lowest peasant if he had the determination and ability to prevail.

Of all the temples in Hanoi, the most beautiful is Van Mieu, the Temple of Literature, dedicated to all those laureates of Vietnam who became mandarins, their names etched on stone steles going back eight centuries.

It was Vietnam’s first university, the Imperial Academy. That it became a temple to the worship of education seems entirely appropriate.

Under French colonial rule, China’s imperial examinations were replaced by the baccalaureate. To have passed its requirements was something so rare that one’s name was forever connected to the title. My paternal grandmother’s closest friend was Ong Tu Tai Quoc – Mr. “Baccalaureate” Quoc.

My paternal grandfather’s baccalaureate took him to Bordeaux to study law and when he returned, he married the daughter of one of the wealthiest men in the Mekong Delta. And for Vietnamese in America, education is everything. So, for someone lucky enough to escape the horrors of post-war Vietnam and be handed through the hard work of his parents the opportunity to become a doctor, to say “no, thank you” was akin to Confucian sin. By refusing to fulfill my expected role within the family, I was being dishonorable. “Selfish,” more than a few relatives called me.

But part of America’s seduction is that it invites betrayal of the parochial. The old culture demands the child to obey and honor the wishes of his parents. America tells him to think for himself and look out for number one. America spurs rebellion of the individual against the communal: follow your dream. It also demands it: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Many children of Asian immigrants learn early to negotiate between the “I” and the “We,” between seemingly opposed ideas and flagrant contradictions, in order to appease and survive in both cultures.

In Vietnam, as a child during the war, I read French comic books and martial arts epics translated from Chinese into Vietnamese, even my mother’s indulgent romance novels. In America, I read American novels and spent my spare time in public libraries, devoting the summers to devouring book after book. When not studying, I was reading. If I was encouraged to mourn the loss of my homeland, I was also glad that I became an American because here, and perhaps nowhere else, as mythologist Joseph Campbell urges, I could follow my passion, my bliss.

Some years passed…

Eavesdropping from upstairs during a visit home, I heard my mother greeting friends and learned of a new addition to our family. “These are Andrew Lam’s awards,” she said, motioning to a bookshelf displaying my trophies, diplomas, and writing awards. “Andrew Lam” was stressed with a tone of importance. “My son, the Berkeley radical,” my father would say by way of talking about me to his friends. “Parents give birth to children,” adds my mother, “God gives birth to their personalities.”

Later that day, I went out to my parent’s backyard for a swim. It was in mid-September when kids were going back to school and leaves had started to turn colors. Though it was sunny out, the water was very cold. I remember standing on tip-toe for a long time at the pool’s edge, fearing the inevitable plunge, yet longing for the seductive blue water. Then, I closed my eyes, took a breath, and leapt. It was cold. But as I adjusted to the temperature and swam, I couldn’t understand why I hesitated for so long.

Finding and following my passion and path in life is a bit like that. Scary. Delightful. A struggle -- to be sure. But once I dove into the pool, I took to the water. And I kept on swimming.

Andrew Lam is the author of "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora" and East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres,"(Heyday).

Eating Reading and Writing An Interview with Andrew Lam

Award-winning author and New American Media editor Andrew Lam discusses his work, contemporary journalism, the complexity of cultural exchange, and what he hopes to see when his work is read in a classroom.

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies: I first met you in person when you came to San Jose State to read from Perfume Dreams in April 2007. As we were leaving the reading, a woman asked you for a good place to eat Vietnamese food in San Jose. I was horrified that someone would essentialize this San Francisco-based writer as a native informant for her culinary desires. As I contemplated tackling her, you very calmly suggested several restaurants and even mentioned that you were working on a book on food. Is that a common experience for you?

ANDREW LAM: It is. I usually don't take offense. I do find, however, that it is annoying when assumedly smart, worldly editors would make that same mistake about me. As a writer, I am capable of writing about many subjects beyond the area of my own cultural background and have done so. I've written about other countries and their troubles- Japan, Thailand, Greece, etc. But when I am asked to write something, or when I am interviewed for something, it is only about Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora.

That is the crutch of being an ethnic writer - one is seen as a cultural ambassador from that community, and then a writer. The only way to break out of that mold is to be big enough in the literary circle so that one can address issues beyond one's biographical limitations.

AALDP: Journalists are often expected to cover a certain beat and to thus be an expert on a particular area, while creative writers frequently assert the uniqueness of their voices or perspectives rather than their representation of a whole group. Alexander Chee in Asian American Literary Review last year comes to mind. Do you feel that these identifications are valid?

AL: I think that used to be more valid than it is now. Part of the reason has to do with the fact that the media world has gone through a major shake up and fewer newspapers exist and while some still practice traditional journalism, that space between reporter and commentator (or essayist) is blurring. Reporters have opinions, after all, and the idea that Fox network seems to spearhead with great success is because people want their supposed reporters to have opinions. The Comedy Channel proves that journalism can in fact be practiced with humor and lots of running jokes and gags and biting observations. So while we still need reporters in the traditional sense, I feel many now are moving sideways across the various spectra of journalism. I myself write news analyses, do straight-forward reporting, and write op-eds. I never feel that I need to restrain myself to one genre. I think as long as I am fair and balanced, and honest with my own biases, I fit in with the new media.

AALDP: This next question also feels old-fashioned now that you have me thinking about

Fox News: how do you negotiate between being a fiction writer and being a journalist?

AL: Not an easy task. I often compare journalism to fiction as architecture is to abstract painting. In the former, one needs to have all the logic and facts at hand.

One needs to build a strong frame and foundation. One needs all the supporting arguments and examples planned out. In the latter, one immerses oneself into the imaginary - but just as real - world, and one needs to step back to let characters grow into well rounded people with their own will. One needs to accept them and then describe them. One needs to feel deeply, empathize deeply. It's very different.

For me, writing nonfiction has become routine. It is still difficult to do creative nonfiction and ideas sometimes refuse to clarify themselves, but overall the process is not daunting. Doing fiction on the other hand, requires lots of time, and solitude, both of which I don't always have since I work as a journalist and editor. Fiction writing can be a foreboding task. Yet the unfinished story calls out for attention and when neglected, characters show up in dreams, in reveries, as if asking: "When are you going to come back to let the drama play out?" They nag at the soul.

AALDP: In your essay “California Cuisine of the World,” in East Eats West, you discuss how Asian food culture has been embraced by the mainstream, at least in California. You write, “private culture has—like sidewalk stalls in Chinatown selling bok choys, string beans, and bitter melons—a knack of spilling into the public sphere, becoming shared convention” (81). You use this image of the private spilling into the public sphere at least two other times in your most recent collection. Do you think of this in terms of loss or gain—as nostalgic loss of the personal and private space or as triumphant claiming of the mainstream as one’s own?

AL: There is something gained and lost in any exchange and it's inevitable. It's a kind of cosmic law of creation. Often immigrants bring their traditional practices with them - think Chinese railroad workers who introduced bamboo and acupuncture with them in the 1800s - and they are always astounded at how quickly those private practices get adopted and transformed by others as well as by their descendants. If I do feel a certain visceral sense of loss seeing pho soup being made by non-Vietnamese I am also generous enough to know how much my cosmopolitan life is so much the richer because other cultures have been integrated into my own life. I think without that sense of generosity one cannot navigate in this complex world of ours. One would have to hide and retreat behind the walls of Little Saigon and Chinatown and treat the larger world as unknown territory.

AALDP: The title for your book, East Eats West, reminds me of listening to Richard

Rodriguez speak in the 1990’s. He talked about interviewing a white supremacist about

the man’s views on Mexican immigrants while the man ate a burrito. He described the

encounter in highly sexualized terms of the supremacist eating the “other.” Do you see

the mainstream popularity of Asian cuisine as a marker of the rising cultural power of

Asians or Asian Americans, or is it just cultural appropriation?

AL: The verb “eat” is so loaded. One can swallow the other, and one can also be swallowed by the other, or be transformed by having ingested something powerful. I play with the idea that both is happening at the same time, which is the essence of my collection of personal essays: It is the story of how a refugee boy from Southeast Asia swallowed America - its myriads of food and movies and language and literature and humor - and is in turn transformed by it. Conversely the other transformation is also happening. Since my arrival in America, I have watched the American landscape be transformed increasingly by the forces of immigration from Asia.

As to your question, in the ‘80s we were terribly afraid of the rise of Japan and consequently we became enthralled with Japanese culture - even as hate crimes against Asians became endemic and that famous case of the murder of Vincent Chin (mistaken for a Japanese) united Asian Americans. I remember falling in love with sushi and Japanese anime in the ‘80s. Others I knew were learning Japanese. Nowadays, it's Korean and Chinese cultures that are becoming global phenomena.

In MBA programs, one is strongly advised to speak another language, and usually it's Mandarin. "You know your cultural heritage is a major success when someone else is selling it back to you,” a friend of mine quipped after I noted the irony that Steven Spielberg produced Kung Fu Panda, which became an all-time box-office hit in China. Kung fu and pandas are both part of China’s heritage, but it probably requires the interpretation of an outsider to make you see your own cultures in new ways.

Cultural appropriation happens both ways as well. Hong Kong used to steal Hollywood blind until they started making really original inventive films and then it was Hollywood that started copying Hong Kong. It cannot be helped. There's a lot of exciting things that can happen when things are "appropriated" because they also get reinvented in the process and newness - ideas, tastes, sounds, movements - come out of that "stealing." All writers "borrow" too from their favorite writers and then find their own voice as they grow. Again, I'd say be generous and see that nothing is really original in the first place. The idea of cultural preservation seems to me a little odd. Cultures that need to be preserved are not fluid and are pickled, as it were. The real culture is what is reinvented to fit the present time, the present palate.

AALDP: I went to high school in Orange County and graduated in 1985—ten years and a

month after the fall of Saigon. The class valedictorian, David Nguyen, was perhaps the

most confident person I have ever met. I have certainly seen Vietnamese Americans of

the 1.5 generation do amazing things in a relatively short space of time after coming to

the United States, but what amazes me about your family’s story is the fact that not only

your generation but your father managed to achieve so much in such a short time: an

MBA and an institutionally and economically powerful position. How did he manage to

do this as an older man and recent immigrant?

AL: My father, Thi Quang Lam, is something of a super-achiever. He was a three star general in the South Vietnam Army (ARVN) and studied French philosophy. Then he spent twenty-five years in the Army. In America he also wrote three books on the Vietnam War in English (then translated them back into Vietnamese for the community). He wrote his first two while working as a bank executive and raising a family of three kids. He just finished his third at 77 last year. He always mourned the fact that he came to the US in his mid 40s instead of mid 20s- because he would have gotten a PhD at the very least and not an MBA.

One of his secrets to success in America is a military trained discipline – which never left him even though he was forced to leave it, his beloved army, at the end of the Vietnam War, which unraveled in 1975. In America he studied nightly, he got up at 5 in the morning to do homework, and exercise. He went to night school while working full time. When he got his MBA, he moved toward writing his memoir and analyses of the Vietnam War, giving details from the South Vietnamese General’s perspective. That sense of duty is chased with an iron will and became key to his success. I can still see it: my father sitting straight back, ramrod, at his desk for hours on end.

Even after retirement, he went on to teach high schools for seven years, and he taught Math, French, Physics. With a third degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do, he even broke bricks in class to demonstrate he was not lying about discipline. He’s quite a self-actualized person in many ways, perhaps an exception for his generation in the US. But his generation was full of brilliant people who never got a chance to achieve their potentials because of the many wars that took place in our homeland. So many were drafted and killed. In fact, that’s one of Vietnam’s greatest tragedies the lost generations. It is no wonder Vietnamese parents in the US are so forceful about their children making it in America – they are haunted by the robbed opportunities experienced by their own generation and those of previous generations.

In Perfume Dreams, I talked about being a Viet Kieu – Vietnamese expat – in Vietnam and how people measured their lost potentials in my own transnational biographies. They touched me. They marveled at my passport and all the entry and exit stamps. I hear phrases like, “Had I escaped to California…” or “If I came to the US at your age, I would have …” all the time. Their bitterness is extra deep because they know so and so who left and achieved great success in the West. Vietnamese, if anything, are a driven, ambitious and competitive people who are cursed with bad luck for being in a place where the superpowers never left them alone to develop in peace.

AALDP: Although you wrote about your father in Perfume Dreams, I think your second

book actually made me think more about your father because of the powerful scene in

which you tell your family that you want to be a writer. That passage struck me as an

almost archetypal image of the parent-child dynamic with you mirroring your father’s

own iron will and writing ambitions even as you distanced yourself from his expectations

for you.

In East Eats West you provide a great metaphor for the economic progress of your life: “I

left the working-class world where Mission Street ended and worked myself toward

where Mission Street began, toward the city’s golden promises—and it is in one of those

glittering glassy towers by the water that I live now” (28). Readers do not need to be

familiar with San Francisco’s housing market to get a sense of what an achievement this

is. How do you think your own class position has affected how you view American

culture? How does economic prosperity affect how one deals with issues of assimilation

or identity?

AL: I came from a privileged background, growing up speaking French, and with servants, chauffeurs, lycée and country club in Vietnam. Perhaps it’s why, having that experience, I am not particularly interested in wealth and status. I have no romantic notion about wealth and status. But I also remember what it was like to go from having an upper class status to being a refugee subsisting at the end of Mission Street in Daly City with other refugee families, and surviving on food stamps and the kindness of various religious charities. In other words, I have been both rich and poor, and now, yes, I am established, with established friends and so on, and my position as writer and journalist enables me to travel the world.

Admittedly, all that makes me feel connected to the cosmopolitan world and people would often describe me as “worldly.” But I hesitate to bring class into discussion about my writing since it often makes human reality seem abstract. Looking at stories through the “class” lens often makes people jump from one ideological conclusion to another. Often enough it never gets to the real stories – the human stories regardless of your economic status– that I want to tell. Economics play a strong part of everyone’s life and yet it also restrains narrative to some ideological bend, which is not what I’m after.

Besides, cosmopolitanism isn’t part of some upper class experience anymore. The migrant who slips across borders learns new ways of speaking and of looking at the world. His children, growing up with two, even three languages in the household, navigate various cultural expectations all the time. People’s fascination seems to be transnational these days, especially among the young. Kids who want to learn Japanese because they watch anime for instance. There’s a Korean restaurant in Berkeley that’s owned and operated by Mexicans who once worked in Korea – we have become, in some way, the other.

AALDP: You have a very optimistic view of cultural hybridity in much of East Eats West. But when you mention all of the terms we now have for mixed race people, you also include terms that can be used pejoratively. Would you say that there is any negative impact from cultural hybridity? How would you characterize Vietnamese attitudes toward the Amerasian children born during and after the war? Do you have a sense of Vietnamese American attitudes toward racial and ethnic mixing?

AL: That’s quite a lot of questions woven into one. I have been accused in the past of painting a rosy picture of East-West relations, especially in the area of cultural exchanges. It is not that I am not unaware of the more sordid, exploitative side of that equation, but it is because I’m interested in what hasn’t been fully explored. Certainly as a reporter and news analyst I’ve written quite a bit on the problems of globalization – racism, exploitation, human trafficking, unfair trading practices, copyrights infringement, accelerated environmental degradation, human rights abuse and so on. But in East Eats West, I wanted to explore what is barely being touched upon –the space where East and West intersect. And I’m not interested in the parameters that the pessimists would insist upon, where the conversation should take place within certain egalitarian ideals. After all, I am westernized by experience and choice, and am Eastern by original inheritances and my marvelous Vietnamese childhood. Part of that enormous complexity came from terrible tragedies – colonization, war, exodus, life in exile. You can be bitter about it, or you can pick and choose, integrating what’s workable into your own life. It’s all about how you synthesize the differences.

Yes, there are terrible combinations of hybridity that shouldn’t even be repeated. Some food combinations are a disaster. But that said, if one frowns on the mixing, the openness to inter-exchanges, one is missing out on the energy that is fusing the major part of the 21st century.

AALDP: I first became familiar with your work through my teaching. First the two short stories anthologized in Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose (1998) and later Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora (2005). How do you feel about your writing being used in the classroom? Is that a space you envision at all when you write? What would you want students to take away from your texts?

AL: A good essay can be as much a visceral experience as it is one in which ideas are transferred. I want readers to feel what it is like to lose a country and all the cultures and societies and customs that went along with it, then have to learn a new language, a new set of behavior, and reinvent a new self, then thrive – that’s the story I want people not only to understand, but experience. But I’d be happy if students went away from reading Perfume Dreams and East Eats West understanding that identities are not fixed in stone, and that after having gone through epic losses one also gains something as well, and new ways of looking at one’s self in place of history.

Perfume Dreams is sadder because it’s closer to the refugee experience, but East Eats West is more celebratory, it’s a regard of life when East and West not only met but became intertwined, creating a hybrid space, as it were, from which new ideas emerged. It is both an internal space, within me, and a cultural and political force of the 21st century.

AALDP: Is there anything you definitely wouldn’t want teachers and students to do with

your texts?

AL: Well, I hope they don’t burn them. But seriously, I think that people often see my work as particularly ethnic and on one level that’s fine. On another, however, I put a lot of effort into playing with language, and structure –and one thing I hope they do pay attention to is the various literary styles in which the essays were written – ranging from the reportorial, to the highly personal, to the little vignettes. I am always thrilled when my work is taught in a literature class because it seems to break some personal barrier for me – to be recognized as a writer in English and not just as an ethnic writer.

AALDP: I have anxiously been awaiting a collection of your short stories. Now I understand Birds of Paradise is due out next year. Will this collect your previously published fiction or will it be pieces we have not seen before?

AL: Many have been published in recent years. But there will be unpublished work as well.

AALDP: Will it include some of my favorite stories such as “Grandma’s Tales” and “Show and Tell?”

AL: I hope so but I fear they might be "eliminated" depending on the tastes of the

editor. But never fear, there are other pieces that might thrill you as well.

Eating Reading and Writing An Interview with Andrew Lam

Award-winning author and New American Media editor Andrew Lam discusses his work, contemporary journalism, the complexity of cultural exchange, and what he hopes to see when his work is read in a classroom.

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies: I first met you in person when you came to San Jose State to read from Perfume Dreams in April 2007. As we were leaving the reading, a woman asked you for a good place to eat Vietnamese food in San Jose. I was horrified that someone would essentialize this San Francisco-based writer as a native informant for her culinary desires. As I contemplated tackling her, you very calmly suggested several restaurants and even mentioned that you were working on a book on food. Is that a common experience for you?

ANDREW LAM: It is. I usually don't take offense. I do find, however, that it is annoying when assumedly smart, worldly editors would make that same mistake about me. As a writer, I am capable of writing about many subjects beyond the area of my own cultural background and have done so. I've written about other countries and their troubles- Japan, Thailand, Greece, etc. But when I am asked to write something, or when I am interviewed for something, it is only about Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora.

That is the crutch of being an ethnic writer - one is seen as a cultural ambassador from that community, and then a writer. The only way to break out of that mold is to be big enough in the literary circle so that one can address issues beyond one's biographical limitations.

AALDP: Journalists are often expected to cover a certain beat and to thus be an expert on a particular area, while creative writers frequently assert the uniqueness of their voices or perspectives rather than their representation of a whole group. Alexander Chee in Asian American Literary Review last year comes to mind. Do you feel that these identifications are valid?

AL: I think that used to be more valid than it is now. Part of the reason has to do with the fact that the media world has gone through a major shake up and fewer newspapers exist and while some still practice traditional journalism, that space between reporter and commentator (or essayist) is blurring. Reporters have opinions, after all, and the idea that Fox network seems to spearhead with great success is because people want their supposed reporters to have opinions. The Comedy Channel proves that journalism can in fact be practiced with humor and lots of running jokes and gags and biting observations. So while we still need reporters in the traditional sense, I feel many now are moving sideways across the various spectra of journalism. I myself write news analyses, do straight-forward reporting, and write op-eds. I never feel that I need to restrain myself to one genre. I think as long as I am fair and balanced, and honest with my own biases, I fit in with the new media.

AALDP: This next question also feels old-fashioned now that you have me thinking about

Fox News: how do you negotiate between being a fiction writer and being a journalist?

AL: Not an easy task. I often compare journalism to fiction as architecture is to abstract painting. In the former, one needs to have all the logic and facts at hand.

One needs to build a strong frame and foundation. One needs all the supporting arguments and examples planned out. In the latter, one immerses oneself into the imaginary - but just as real - world, and one needs to step back to let characters grow into well rounded people with their own will. One needs to accept them and then describe them. One needs to feel deeply, empathize deeply. It's very different.

For me, writing nonfiction has become routine. It is still difficult to do creative nonfiction and ideas sometimes refuse to clarify themselves, but overall the process is not daunting. Doing fiction on the other hand, requires lots of time, and solitude, both of which I don't always have since I work as a journalist and editor. Fiction writing can be a foreboding task. Yet the unfinished story calls out for attention and when neglected, characters show up in dreams, in reveries, as if asking: "When are you going to come back to let the drama play out?" They nag at the soul.

AALDP: In your essay “California Cuisine of the World,” in East Eats West, you discuss how Asian food culture has been embraced by the mainstream, at least in California. You write, “private culture has—like sidewalk stalls in Chinatown selling bok choys, string beans, and bitter melons—a knack of spilling into the public sphere, becoming shared convention” (81). You use this image of the private spilling into the public sphere at least two other times in your most recent collection. Do you think of this in terms of loss or gain—as nostalgic loss of the personal and private space or as triumphant claiming of the mainstream as one’s own?

AL: There is something gained and lost in any exchange and it's inevitable. It's a kind of cosmic law of creation. Often immigrants bring their traditional practices with them - think Chinese railroad workers who introduced bamboo and acupuncture with them in the 1800s - and they are always astounded at how quickly those private practices get adopted and transformed by others as well as by their descendants. If I do feel a certain visceral sense of loss seeing pho soup being made by non-Vietnamese I am also generous enough to know how much my cosmopolitan life is so much the richer because other cultures have been integrated into my own life. I think without that sense of generosity one cannot navigate in this complex world of ours. One would have to hide and retreat behind the walls of Little Saigon and Chinatown and treat the larger world as unknown territory.

AALDP: The title for your book, East Eats West, reminds me of listening to Richard

Rodriguez speak in the 1990’s. He talked about interviewing a white supremacist about

the man’s views on Mexican immigrants while the man ate a burrito. He described the

encounter in highly sexualized terms of the supremacist eating the “other.” Do you see

the mainstream popularity of Asian cuisine as a marker of the rising cultural power of

Asians or Asian Americans, or is it just cultural appropriation?

AL: The verb “eat” is so loaded. One can swallow the other, and one can also be swallowed by the other, or be transformed by having ingested something powerful. I play with the idea that both is happening at the same time, which is the essence of my collection of personal essays: It is the story of how a refugee boy from Southeast Asia swallowed America - its myriads of food and movies and language and literature and humor - and is in turn transformed by it. Conversely the other transformation is also happening. Since my arrival in America, I have watched the American landscape be transformed increasingly by the forces of immigration from Asia.

As to your question, in the ‘80s we were terribly afraid of the rise of Japan and consequently we became enthralled with Japanese culture - even as hate crimes against Asians became endemic and that famous case of the murder of Vincent Chin (mistaken for a Japanese) united Asian Americans. I remember falling in love with sushi and Japanese anime in the ‘80s. Others I knew were learning Japanese. Nowadays, it's Korean and Chinese cultures that are becoming global phenomena.

In MBA programs, one is strongly advised to speak another language, and usually it's Mandarin. "You know your cultural heritage is a major success when someone else is selling it back to you,” a friend of mine quipped after I noted the irony that Steven Spielberg produced Kung Fu Panda, which became an all-time box-office hit in China. Kung fu and pandas are both part of China’s heritage, but it probably requires the interpretation of an outsider to make you see your own cultures in new ways.

Cultural appropriation happens both ways as well. Hong Kong used to steal Hollywood blind until they started making really original inventive films and then it was Hollywood that started copying Hong Kong. It cannot be helped. There's a lot of exciting things that can happen when things are "appropriated" because they also get reinvented in the process and newness - ideas, tastes, sounds, movements - come out of that "stealing." All writers "borrow" too from their favorite writers and then find their own voice as they grow. Again, I'd say be generous and see that nothing is really original in the first place. The idea of cultural preservation seems to me a little odd. Cultures that need to be preserved are not fluid and are pickled, as it were. The real culture is what is reinvented to fit the present time, the present palate.

AALDP: I went to high school in Orange County and graduated in 1985—ten years and a

month after the fall of Saigon. The class valedictorian, David Nguyen, was perhaps the

most confident person I have ever met. I have certainly seen Vietnamese Americans of

the 1.5 generation do amazing things in a relatively short space of time after coming to

the United States, but what amazes me about your family’s story is the fact that not only

your generation but your father managed to achieve so much in such a short time: an

MBA and an institutionally and economically powerful position. How did he manage to

do this as an older man and recent immigrant?

AL: My father, Thi Quang Lam, is something of a super-achiever. He was a three star general in the South Vietnam Army (ARVN) and studied French philosophy. Then he spent twenty-five years in the Army. In America he also wrote three books on the Vietnam War in English (then translated them back into Vietnamese for the community). He wrote his first two while working as a bank executive and raising a family of three kids. He just finished his third at 77 last year. He always mourned the fact that he came to the US in his mid 40s instead of mid 20s- because he would have gotten a PhD at the very least and not an MBA.

One of his secrets to success in America is a military trained discipline – which never left him even though he was forced to leave it, his beloved army, at the end of the Vietnam War, which unraveled in 1975. In America he studied nightly, he got up at 5 in the morning to do homework, and exercise. He went to night school while working full time. When he got his MBA, he moved toward writing his memoir and analyses of the Vietnam War, giving details from the South Vietnamese General’s perspective. That sense of duty is chased with an iron will and became key to his success. I can still see it: my father sitting straight back, ramrod, at his desk for hours on end.

Even after retirement, he went on to teach high schools for seven years, and he taught Math, French, Physics. With a third degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do, he even broke bricks in class to demonstrate he was not lying about discipline. He’s quite a self-actualized person in many ways, perhaps an exception for his generation in the US. But his generation was full of brilliant people who never got a chance to achieve their potentials because of the many wars that took place in our homeland. So many were drafted and killed. In fact, that’s one of Vietnam’s greatest tragedies the lost generations. It is no wonder Vietnamese parents in the US are so forceful about their children making it in America – they are haunted by the robbed opportunities experienced by their own generation and those of previous generations.

In Perfume Dreams, I talked about being a Viet Kieu – Vietnamese expat – in Vietnam and how people measured their lost potentials in my own transnational biographies. They touched me. They marveled at my passport and all the entry and exit stamps. I hear phrases like, “Had I escaped to California…” or “If I came to the US at your age, I would have …” all the time. Their bitterness is extra deep because they know so and so who left and achieved great success in the West. Vietnamese, if anything, are a driven, ambitious and competitive people who are cursed with bad luck for being in a place where the superpowers never left them alone to develop in peace.

AALDP: Although you wrote about your father in Perfume Dreams, I think your second

book actually made me think more about your father because of the powerful scene in

which you tell your family that you want to be a writer. That passage struck me as an

almost archetypal image of the parent-child dynamic with you mirroring your father’s

own iron will and writing ambitions even as you distanced yourself from his expectations

for you.

In East Eats West you provide a great metaphor for the economic progress of your life: “I

left the working-class world where Mission Street ended and worked myself toward

where Mission Street began, toward the city’s golden promises—and it is in one of those

glittering glassy towers by the water that I live now” (28). Readers do not need to be

familiar with San Francisco’s housing market to get a sense of what an achievement this

is. How do you think your own class position has affected how you view American

culture? How does economic prosperity affect how one deals with issues of assimilation

or identity?

AL: I came from a privileged background, growing up speaking French, and with servants, chauffeurs, lycée and country club in Vietnam. Perhaps it’s why, having that experience, I am not particularly interested in wealth and status. I have no romantic notion about wealth and status. But I also remember what it was like to go from having an upper class status to being a refugee subsisting at the end of Mission Street in Daly City with other refugee families, and surviving on food stamps and the kindness of various religious charities. In other words, I have been both rich and poor, and now, yes, I am established, with established friends and so on, and my position as writer and journalist enables me to travel the world.

Admittedly, all that makes me feel connected to the cosmopolitan world and people would often describe me as “worldly.” But I hesitate to bring class into discussion about my writing since it often makes human reality seem abstract. Looking at stories through the “class” lens often makes people jump from one ideological conclusion to another. Often enough it never gets to the real stories – the human stories regardless of your economic status– that I want to tell. Economics play a strong part of everyone’s life and yet it also restrains narrative to some ideological bend, which is not what I’m after.

Besides, cosmopolitanism isn’t part of some upper class experience anymore. The migrant who slips across borders learns new ways of speaking and of looking at the world. His children, growing up with two, even three languages in the household, navigate various cultural expectations all the time. People’s fascination seems to be transnational these days, especially among the young. Kids who want to learn Japanese because they watch anime for instance. There’s a Korean restaurant in Berkeley that’s owned and operated by Mexicans who once worked in Korea – we have become, in some way, the other.

AALDP: You have a very optimistic view of cultural hybridity in much of East Eats West. But when you mention all of the terms we now have for mixed race people, you also include terms that can be used pejoratively. Would you say that there is any negative impact from cultural hybridity? How would you characterize Vietnamese attitudes toward the Amerasian children born during and after the war? Do you have a sense of Vietnamese American attitudes toward racial and ethnic mixing?

AL: That’s quite a lot of questions woven into one. I have been accused in the past of painting a rosy picture of East-West relations, especially in the area of cultural exchanges. It is not that I am not unaware of the more sordid, exploitative side of that equation, but it is because I’m interested in what hasn’t been fully explored. Certainly as a reporter and news analyst I’ve written quite a bit on the problems of globalization – racism, exploitation, human trafficking, unfair trading practices, copyrights infringement, accelerated environmental degradation, human rights abuse and so on. But in East Eats West, I wanted to explore what is barely being touched upon –the space where East and West intersect. And I’m not interested in the parameters that the pessimists would insist upon, where the conversation should take place within certain egalitarian ideals. After all, I am westernized by experience and choice, and am Eastern by original inheritances and my marvelous Vietnamese childhood. Part of that enormous complexity came from terrible tragedies – colonization, war, exodus, life in exile. You can be bitter about it, or you can pick and choose, integrating what’s workable into your own life. It’s all about how you synthesize the differences.

Yes, there are terrible combinations of hybridity that shouldn’t even be repeated. Some food combinations are a disaster. But that said, if one frowns on the mixing, the openness to inter-exchanges, one is missing out on the energy that is fusing the major part of the 21st century.

AALDP: I first became familiar with your work through my teaching. First the two short stories anthologized in Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose (1998) and later Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora (2005). How do you feel about your writing being used in the classroom? Is that a space you envision at all when you write? What would you want students to take away from your texts?

AL: A good essay can be as much a visceral experience as it is one in which ideas are transferred. I want readers to feel what it is like to lose a country and all the cultures and societies and customs that went along with it, then have to learn a new language, a new set of behavior, and reinvent a new self, then thrive – that’s the story I want people not only to understand, but experience. But I’d be happy if students went away from reading Perfume Dreams and East Eats West understanding that identities are not fixed in stone, and that after having gone through epic losses one also gains something as well, and new ways of looking at one’s self in place of history.

Perfume Dreams is sadder because it’s closer to the refugee experience, but East Eats West is more celebratory, it’s a regard of life when East and West not only met but became intertwined, creating a hybrid space, as it were, from which new ideas emerged. It is both an internal space, within me, and a cultural and political force of the 21st century.

AALDP: Is there anything you definitely wouldn’t want teachers and students to do with

your texts?

AL: Well, I hope they don’t burn them. But seriously, I think that people often see my work as particularly ethnic and on one level that’s fine. On another, however, I put a lot of effort into playing with language, and structure –and one thing I hope they do pay attention to is the various literary styles in which the essays were written – ranging from the reportorial, to the highly personal, to the little vignettes. I am always thrilled when my work is taught in a literature class because it seems to break some personal barrier for me – to be recognized as a writer in English and not just as an ethnic writer.

AALDP: I have anxiously been awaiting a collection of your short stories. Now I understand Birds of Paradise is due out next year. Will this collect your previously published fiction or will it be pieces we have not seen before?

AL: Many have been published in recent years. But there will be unpublished work as well.

AALDP: Will it include some of my favorite stories such as “Grandma’s Tales” and “Show and Tell?”

AL: I hope so but I fear they might be "eliminated" depending on the tastes of the

editor. But never fear, there are other pieces that might thrill you as well.

Eating Reading and Writing An Interview with Andrew Lam

Award-winning author and New American Media editor Andrew Lam discusses his work, contemporary journalism, the complexity of cultural exchange, and what he hopes to see when his work is read in a classroom.

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies: I first met you in person when you came to San Jose State to read from Perfume Dreams in April 2007. As we were leaving the reading, a woman asked you for a good place to eat Vietnamese food in San Jose. I was horrified that someone would essentialize this San Francisco-based writer as a native informant for her culinary desires. As I contemplated tackling her, you very calmly suggested several restaurants and even mentioned that you were working on a book on food. Is that a common experience for you?

ANDREW LAM: It is. I usually don't take offense. I do find, however, that it is annoying when assumedly smart, worldly editors would make that same mistake about me. As a writer, I am capable of writing about many subjects beyond the area of my own cultural background and have done so. I've written about other countries and their troubles- Japan, Thailand, Greece, etc. But when I am asked to write something, or when I am interviewed for something, it is only about Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora.

That is the crutch of being an ethnic writer - one is seen as a cultural ambassador from that community, and then a writer. The only way to break out of that mold is to be big enough in the literary circle so that one can address issues beyond one's biographical limitations.

AALDP: Journalists are often expected to cover a certain beat and to thus be an expert on a particular area, while creative writers frequently assert the uniqueness of their voices or perspectives rather than their representation of a whole group. Alexander Chee in Asian American Literary Review last year comes to mind. Do you feel that these identifications are valid?

AL: I think that used to be more valid than it is now. Part of the reason has to do with the fact that the media world has gone through a major shake up and fewer newspapers exist and while some still practice traditional journalism, that space between reporter and commentator (or essayist) is blurring. Reporters have opinions, after all, and the idea that Fox network seems to spearhead with great success is because people want their supposed reporters to have opinions. The Comedy Channel proves that journalism can in fact be practiced with humor and lots of running jokes and gags and biting observations. So while we still need reporters in the traditional sense, I feel many now are moving sideways across the various spectra of journalism. I myself write news analyses, do straight-forward reporting, and write op-eds. I never feel that I need to restrain myself to one genre. I think as long as I am fair and balanced, and honest with my own biases, I fit in with the new media.

AALDP: This next question also feels old-fashioned now that you have me thinking about

Fox News: how do you negotiate between being a fiction writer and being a journalist?

AL: Not an easy task. I often compare journalism to fiction as architecture is to abstract painting. In the former, one needs to have all the logic and facts at hand.

One needs to build a strong frame and foundation. One needs all the supporting arguments and examples planned out. In the latter, one immerses oneself into the imaginary - but just as real - world, and one needs to step back to let characters grow into well rounded people with their own will. One needs to accept them and then describe them. One needs to feel deeply, empathize deeply. It's very different.

For me, writing nonfiction has become routine. It is still difficult to do creative nonfiction and ideas sometimes refuse to clarify themselves, but overall the process is not daunting. Doing fiction on the other hand, requires lots of time, and solitude, both of which I don't always have since I work as a journalist and editor. Fiction writing can be a foreboding task. Yet the unfinished story calls out for attention and when neglected, characters show up in dreams, in reveries, as if asking: "When are you going to come back to let the drama play out?" They nag at the soul.

AALDP: In your essay “California Cuisine of the World,” in East Eats West, you discuss how Asian food culture has been embraced by the mainstream, at least in California. You write, “private culture has—like sidewalk stalls in Chinatown selling bok choys, string beans, and bitter melons—a knack of spilling into the public sphere, becoming shared convention” (81). You use this image of the private spilling into the public sphere at least two other times in your most recent collection. Do you think of this in terms of loss or gain—as nostalgic loss of the personal and private space or as triumphant claiming of the mainstream as one’s own?

AL: There is something gained and lost in any exchange and it's inevitable. It's a kind of cosmic law of creation. Often immigrants bring their traditional practices with them - think Chinese railroad workers who introduced bamboo and acupuncture with them in the 1800s - and they are always astounded at how quickly those private practices get adopted and transformed by others as well as by their descendants. If I do feel a certain visceral sense of loss seeing pho soup being made by non-Vietnamese I am also generous enough to know how much my cosmopolitan life is so much the richer because other cultures have been integrated into my own life. I think without that sense of generosity one cannot navigate in this complex world of ours. One would have to hide and retreat behind the walls of Little Saigon and Chinatown and treat the larger world as unknown territory.

AALDP: The title for your book, East Eats West, reminds me of listening to Richard

Rodriguez speak in the 1990’s. He talked about interviewing a white supremacist about

the man’s views on Mexican immigrants while the man ate a burrito. He described the

encounter in highly sexualized terms of the supremacist eating the “other.” Do you see

the mainstream popularity of Asian cuisine as a marker of the rising cultural power of

Asians or Asian Americans, or is it just cultural appropriation?

AL: The verb “eat” is so loaded. One can swallow the other, and one can also be swallowed by the other, or be transformed by having ingested something powerful. I play with the idea that both is happening at the same time, which is the essence of my collection of personal essays: It is the story of how a refugee boy from Southeast Asia swallowed America - its myriads of food and movies and language and literature and humor - and is in turn transformed by it. Conversely the other transformation is also happening. Since my arrival in America, I have watched the American landscape be transformed increasingly by the forces of immigration from Asia.

As to your question, in the ‘80s we were terribly afraid of the rise of Japan and consequently we became enthralled with Japanese culture - even as hate crimes against Asians became endemic and that famous case of the murder of Vincent Chin (mistaken for a Japanese) united Asian Americans. I remember falling in love with sushi and Japanese anime in the ‘80s. Others I knew were learning Japanese. Nowadays, it's Korean and Chinese cultures that are becoming global phenomena.

In MBA programs, one is strongly advised to speak another language, and usually it's Mandarin. "You know your cultural heritage is a major success when someone else is selling it back to you,” a friend of mine quipped after I noted the irony that Steven Spielberg produced Kung Fu Panda, which became an all-time box-office hit in China. Kung fu and pandas are both part of China’s heritage, but it probably requires the interpretation of an outsider to make you see your own cultures in new ways.

Cultural appropriation happens both ways as well. Hong Kong used to steal Hollywood blind until they started making really original inventive films and then it was Hollywood that started copying Hong Kong. It cannot be helped. There's a lot of exciting things that can happen when things are "appropriated" because they also get reinvented in the process and newness - ideas, tastes, sounds, movements - come out of that "stealing." All writers "borrow" too from their favorite writers and then find their own voice as they grow. Again, I'd say be generous and see that nothing is really original in the first place. The idea of cultural preservation seems to me a little odd. Cultures that need to be preserved are not fluid and are pickled, as it were. The real culture is what is reinvented to fit the present time, the present palate.

AALDP: I went to high school in Orange County and graduated in 1985—ten years and a

month after the fall of Saigon. The class valedictorian, David Nguyen, was perhaps the

most confident person I have ever met. I have certainly seen Vietnamese Americans of

the 1.5 generation do amazing things in a relatively short space of time after coming to

the United States, but what amazes me about your family’s story is the fact that not only

your generation but your father managed to achieve so much in such a short time: an

MBA and an institutionally and economically powerful position. How did he manage to

do this as an older man and recent immigrant?

AL: My father, Thi Quang Lam, is something of a super-achiever. He was a three star general in the South Vietnam Army (ARVN) and studied French philosophy. Then he spent twenty-five years in the Army. In America he also wrote three books on the Vietnam War in English (then translated them back into Vietnamese for the community). He wrote his first two while working as a bank executive and raising a family of three kids. He just finished his third at 77 last year. He always mourned the fact that he came to the US in his mid 40s instead of mid 20s- because he would have gotten a PhD at the very least and not an MBA.

One of his secrets to success in America is a military trained discipline – which never left him even though he was forced to leave it, his beloved army, at the end of the Vietnam War, which unraveled in 1975. In America he studied nightly, he got up at 5 in the morning to do homework, and exercise. He went to night school while working full time. When he got his MBA, he moved toward writing his memoir and analyses of the Vietnam War, giving details from the South Vietnamese General’s perspective. That sense of duty is chased with an iron will and became key to his success. I can still see it: my father sitting straight back, ramrod, at his desk for hours on end.

Even after retirement, he went on to teach high schools for seven years, and he taught Math, French, Physics. With a third degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do, he even broke bricks in class to demonstrate he was not lying about discipline. He’s quite a self-actualized person in many ways, perhaps an exception for his generation in the US. But his generation was full of brilliant people who never got a chance to achieve their potentials because of the many wars that took place in our homeland. So many were drafted and killed. In fact, that’s one of Vietnam’s greatest tragedies the lost generations. It is no wonder Vietnamese parents in the US are so forceful about their children making it in America – they are haunted by the robbed opportunities experienced by their own generation and those of previous generations.

In Perfume Dreams, I talked about being a Viet Kieu – Vietnamese expat – in Vietnam and how people measured their lost potentials in my own transnational biographies. They touched me. They marveled at my passport and all the entry and exit stamps. I hear phrases like, “Had I escaped to California…” or “If I came to the US at your age, I would have …” all the time. Their bitterness is extra deep because they know so and so who left and achieved great success in the West. Vietnamese, if anything, are a driven, ambitious and competitive people who are cursed with bad luck for being in a place where the superpowers never left them alone to develop in peace.

AALDP: Although you wrote about your father in Perfume Dreams, I think your second

book actually made me think more about your father because of the powerful scene in

which you tell your family that you want to be a writer. That passage struck me as an

almost archetypal image of the parent-child dynamic with you mirroring your father’s

own iron will and writing ambitions even as you distanced yourself from his expectations

for you.

In East Eats West you provide a great metaphor for the economic progress of your life: “I

left the working-class world where Mission Street ended and worked myself toward

where Mission Street began, toward the city’s golden promises—and it is in one of those

glittering glassy towers by the water that I live now” (28). Readers do not need to be

familiar with San Francisco’s housing market to get a sense of what an achievement this

is. How do you think your own class position has affected how you view American

culture? How does economic prosperity affect how one deals with issues of assimilation

or identity?

AL: I came from a privileged background, growing up speaking French, and with servants, chauffeurs, lycée and country club in Vietnam. Perhaps it’s why, having that experience, I am not particularly interested in wealth and status. I have no romantic notion about wealth and status. But I also remember what it was like to go from having an upper class status to being a refugee subsisting at the end of Mission Street in Daly City with other refugee families, and surviving on food stamps and the kindness of various religious charities. In other words, I have been both rich and poor, and now, yes, I am established, with established friends and so on, and my position as writer and journalist enables me to travel the world.

Admittedly, all that makes me feel connected to the cosmopolitan world and people would often describe me as “worldly.” But I hesitate to bring class into discussion about my writing since it often makes human reality seem abstract. Looking at stories through the “class” lens often makes people jump from one ideological conclusion to another. Often enough it never gets to the real stories – the human stories regardless of your economic status– that I want to tell. Economics play a strong part of everyone’s life and yet it also restrains narrative to some ideological bend, which is not what I’m after.

Besides, cosmopolitanism isn’t part of some upper class experience anymore. The migrant who slips across borders learns new ways of speaking and of looking at the world. His children, growing up with two, even three languages in the household, navigate various cultural expectations all the time. People’s fascination seems to be transnational these days, especially among the young. Kids who want to learn Japanese because they watch anime for instance. There’s a Korean restaurant in Berkeley that’s owned and operated by Mexicans who once worked in Korea – we have become, in some way, the other.

AALDP: You have a very optimistic view of cultural hybridity in much of East Eats West. But when you mention all of the terms we now have for mixed race people, you also include terms that can be used pejoratively. Would you say that there is any negative impact from cultural hybridity? How would you characterize Vietnamese attitudes toward the Amerasian children born during and after the war? Do you have a sense of Vietnamese American attitudes toward racial and ethnic mixing?

AL: That’s quite a lot of questions woven into one. I have been accused in the past of painting a rosy picture of East-West relations, especially in the area of cultural exchanges. It is not that I am not unaware of the more sordid, exploitative side of that equation, but it is because I’m interested in what hasn’t been fully explored. Certainly as a reporter and news analyst I’ve written quite a bit on the problems of globalization – racism, exploitation, human trafficking, unfair trading practices, copyrights infringement, accelerated environmental degradation, human rights abuse and so on. But in East Eats West, I wanted to explore what is barely being touched upon –the space where East and West intersect. And I’m not interested in the parameters that the pessimists would insist upon, where the conversation should take place within certain egalitarian ideals. After all, I am westernized by experience and choice, and am Eastern by original inheritances and my marvelous Vietnamese childhood. Part of that enormous complexity came from terrible tragedies – colonization, war, exodus, life in exile. You can be bitter about it, or you can pick and choose, integrating what’s workable into your own life. It’s all about how you synthesize the differences.

Yes, there are terrible combinations of hybridity that shouldn’t even be repeated. Some food combinations are a disaster. But that said, if one frowns on the mixing, the openness to inter-exchanges, one is missing out on the energy that is fusing the major part of the 21st century.

AALDP: I first became familiar with your work through my teaching. First the two short stories anthologized in Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose (1998) and later Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora (2005). How do you feel about your writing being used in the classroom? Is that a space you envision at all when you write? What would you want students to take away from your texts?

AL: A good essay can be as much a visceral experience as it is one in which ideas are transferred. I want readers to feel what it is like to lose a country and all the cultures and societies and customs that went along with it, then have to learn a new language, a new set of behavior, and reinvent a new self, then thrive – that’s the story I want people not only to understand, but experience. But I’d be happy if students went away from reading Perfume Dreams and East Eats West understanding that identities are not fixed in stone, and that after having gone through epic losses one also gains something as well, and new ways of looking at one’s self in place of history.

Perfume Dreams is sadder because it’s closer to the refugee experience, but East Eats West is more celebratory, it’s a regard of life when East and West not only met but became intertwined, creating a hybrid space, as it were, from which new ideas emerged. It is both an internal space, within me, and a cultural and political force of the 21st century.

AALDP: Is there anything you definitely wouldn’t want teachers and students to do with

your texts?

AL: Well, I hope they don’t burn them. But seriously, I think that people often see my work as particularly ethnic and on one level that’s fine. On another, however, I put a lot of effort into playing with language, and structure –and one thing I hope they do pay attention to is the various literary styles in which the essays were written – ranging from the reportorial, to the highly personal, to the little vignettes. I am always thrilled when my work is taught in a literature class because it seems to break some personal barrier for me – to be recognized as a writer in English and not just as an ethnic writer.

AALDP: I have anxiously been awaiting a collection of your short stories. Now I understand Birds of Paradise is due out next year. Will this collect your previously published fiction or will it be pieces we have not seen before?

AL: Many have been published in recent years. But there will be unpublished work as well.

AALDP: Will it include some of my favorite stories such as “Grandma’s Tales” and “Show and Tell?”

AL: I hope so but I fear they might be "eliminated" depending on the tastes of the

editor. But never fear, there are other pieces that might thrill you as well.

Eating Reading and Writing An Interview with Andrew Lam

Award-winning author and New American Media editor Andrew Lam discusses his work, contemporary journalism, the complexity of cultural exchange, and what he hopes to see when his work is read in a classroom.

Asian American Literature: Discourses and Pedagogies: I first met you in person when you came to San Jose State to read from Perfume Dreams in April 2007. As we were leaving the reading, a woman asked you for a good place to eat Vietnamese food in San Jose. I was horrified that someone would essentialize this San Francisco-based writer as a native informant for her culinary desires. As I contemplated tackling her, you very calmly suggested several restaurants and even mentioned that you were working on a book on food. Is that a common experience for you?

ANDREW LAM: It is. I usually don't take offense. I do find, however, that it is annoying when assumedly smart, worldly editors would make that same mistake about me. As a writer, I am capable of writing about many subjects beyond the area of my own cultural background and have done so. I've written about other countries and their troubles- Japan, Thailand, Greece, etc. But when I am asked to write something, or when I am interviewed for something, it is only about Vietnam and the Vietnamese Diaspora.

That is the crutch of being an ethnic writer - one is seen as a cultural ambassador from that community, and then a writer. The only way to break out of that mold is to be big enough in the literary circle so that one can address issues beyond one's biographical limitations.

AALDP: Journalists are often expected to cover a certain beat and to thus be an expert on a particular area, while creative writers frequently assert the uniqueness of their voices or perspectives rather than their representation of a whole group. Alexander Chee in Asian American Literary Review last year comes to mind. Do you feel that these identifications are valid?

AL: I think that used to be more valid than it is now. Part of the reason has to do with the fact that the media world has gone through a major shake up and fewer newspapers exist and while some still practice traditional journalism, that space between reporter and commentator (or essayist) is blurring. Reporters have opinions, after all, and the idea that Fox network seems to spearhead with great success is because people want their supposed reporters to have opinions. The Comedy Channel proves that journalism can in fact be practiced with humor and lots of running jokes and gags and biting observations. So while we still need reporters in the traditional sense, I feel many now are moving sideways across the various spectra of journalism. I myself write news analyses, do straight-forward reporting, and write op-eds. I never feel that I need to restrain myself to one genre. I think as long as I am fair and balanced, and honest with my own biases, I fit in with the new media.

AALDP: This next question also feels old-fashioned now that you have me thinking about

Fox News: how do you negotiate between being a fiction writer and being a journalist?

AL: Not an easy task. I often compare journalism to fiction as architecture is to abstract painting. In the former, one needs to have all the logic and facts at hand.

One needs to build a strong frame and foundation. One needs all the supporting arguments and examples planned out. In the latter, one immerses oneself into the imaginary - but just as real - world, and one needs to step back to let characters grow into well rounded people with their own will. One needs to accept them and then describe them. One needs to feel deeply, empathize deeply. It's very different.

For me, writing nonfiction has become routine. It is still difficult to do creative nonfiction and ideas sometimes refuse to clarify themselves, but overall the process is not daunting. Doing fiction on the other hand, requires lots of time, and solitude, both of which I don't always have since I work as a journalist and editor. Fiction writing can be a foreboding task. Yet the unfinished story calls out for attention and when neglected, characters show up in dreams, in reveries, as if asking: "When are you going to come back to let the drama play out?" They nag at the soul.

AALDP: In your essay “California Cuisine of the World,” in East Eats West, you discuss how Asian food culture has been embraced by the mainstream, at least in California. You write, “private culture has—like sidewalk stalls in Chinatown selling bok choys, string beans, and bitter melons—a knack of spilling into the public sphere, becoming shared convention” (81). You use this image of the private spilling into the public sphere at least two other times in your most recent collection. Do you think of this in terms of loss or gain—as nostalgic loss of the personal and private space or as triumphant claiming of the mainstream as one’s own?

AL: There is something gained and lost in any exchange and it's inevitable. It's a kind of cosmic law of creation. Often immigrants bring their traditional practices with them - think Chinese railroad workers who introduced bamboo and acupuncture with them in the 1800s - and they are always astounded at how quickly those private practices get adopted and transformed by others as well as by their descendants. If I do feel a certain visceral sense of loss seeing pho soup being made by non-Vietnamese I am also generous enough to know how much my cosmopolitan life is so much the richer because other cultures have been integrated into my own life. I think without that sense of generosity one cannot navigate in this complex world of ours. One would have to hide and retreat behind the walls of Little Saigon and Chinatown and treat the larger world as unknown territory.

AALDP: The title for your book, East Eats West, reminds me of listening to Richard

Rodriguez speak in the 1990’s. He talked about interviewing a white supremacist about

the man’s views on Mexican immigrants while the man ate a burrito. He described the

encounter in highly sexualized terms of the supremacist eating the “other.” Do you see

the mainstream popularity of Asian cuisine as a marker of the rising cultural power of

Asians or Asian Americans, or is it just cultural appropriation?

AL: The verb “eat” is so loaded. One can swallow the other, and one can also be swallowed by the other, or be transformed by having ingested something powerful. I play with the idea that both is happening at the same time, which is the essence of my collection of personal essays: It is the story of how a refugee boy from Southeast Asia swallowed America - its myriads of food and movies and language and literature and humor - and is in turn transformed by it. Conversely the other transformation is also happening. Since my arrival in America, I have watched the American landscape be transformed increasingly by the forces of immigration from Asia.

As to your question, in the ‘80s we were terribly afraid of the rise of Japan and consequently we became enthralled with Japanese culture - even as hate crimes against Asians became endemic and that famous case of the murder of Vincent Chin (mistaken for a Japanese) united Asian Americans. I remember falling in love with sushi and Japanese anime in the ‘80s. Others I knew were learning Japanese. Nowadays, it's Korean and Chinese cultures that are becoming global phenomena.

In MBA programs, one is strongly advised to speak another language, and usually it's Mandarin. "You know your cultural heritage is a major success when someone else is selling it back to you,” a friend of mine quipped after I noted the irony that Steven Spielberg produced Kung Fu Panda, which became an all-time box-office hit in China. Kung fu and pandas are both part of China’s heritage, but it probably requires the interpretation of an outsider to make you see your own cultures in new ways.

Cultural appropriation happens both ways as well. Hong Kong used to steal Hollywood blind until they started making really original inventive films and then it was Hollywood that started copying Hong Kong. It cannot be helped. There's a lot of exciting things that can happen when things are "appropriated" because they also get reinvented in the process and newness - ideas, tastes, sounds, movements - come out of that "stealing." All writers "borrow" too from their favorite writers and then find their own voice as they grow. Again, I'd say be generous and see that nothing is really original in the first place. The idea of cultural preservation seems to me a little odd. Cultures that need to be preserved are not fluid and are pickled, as it were. The real culture is what is reinvented to fit the present time, the present palate.

AALDP: I went to high school in Orange County and graduated in 1985—ten years and a

month after the fall of Saigon. The class valedictorian, David Nguyen, was perhaps the

most confident person I have ever met. I have certainly seen Vietnamese Americans of

the 1.5 generation do amazing things in a relatively short space of time after coming to

the United States, but what amazes me about your family’s story is the fact that not only

your generation but your father managed to achieve so much in such a short time: an

MBA and an institutionally and economically powerful position. How did he manage to

do this as an older man and recent immigrant?

AL: My father, Thi Quang Lam, is something of a super-achiever. He was a three star general in the South Vietnam Army (ARVN) and studied French philosophy. Then he spent twenty-five years in the Army. In America he also wrote three books on the Vietnam War in English (then translated them back into Vietnamese for the community). He wrote his first two while working as a bank executive and raising a family of three kids. He just finished his third at 77 last year. He always mourned the fact that he came to the US in his mid 40s instead of mid 20s- because he would have gotten a PhD at the very least and not an MBA.