Andrew Lam's Blog - Posts Tagged "writing-life"

'Birds of Paradise Lost': A Conversation With Author Andrew Lam

Anna Challet: Birds of Paradise Lost is your first book of fiction - how did you come to publish a fiction collection after so many years of working as a journalist?

Andrew Lam: I've been writing short stories for twenty years now, on and off ever since I was in the creative writing program at San Francisco State University. Though I later found a career as a journalist and an essayist, fiction is my first love and I never left it, even though there was no easy way to make a living from it. The collection is a labor of love and devotion, and whenever I found free time from my journalism work, I'd work on one story or another, or at least sketch out my characters, and research various issues related to my characters' dilemmas. After twenty years and thirty stories, thirteen pieces were finally selected and the collection was born. So far, the blurbs from [authors] Maxine Hong Kingston, Gish Jen, Robert Olen Butler, Oscar Hijuelos, Sandip Roy and others, have been most encouraging.

AC: You've written many personal essays and non-fiction pieces about coming to the United States from Vietnam. How does it feel to bring that experience into the lives of your fictional characters?

AL: Well, I always say that writing non-fiction versus writing fiction is a bit like architecture versus abstract painting. In non-fiction you have to stay true to historical events, be they personal or national ... In fiction, it's as if you enter a dream world that you created, but your characters have their own free will. They don't do what you want them to do - they get into trouble, do drugs, fight over petty things, and do outrageous things that you wouldn't want your children to do. In other words, you can only provide the background, the seeds - in my case the background of the Vietnamese refugee. When a well-rounded character takes over, he doesn't lecture you about his history and how he is misunderstood. He lives his life, does things that are unexpected, and makes you laugh and cry because of his human flaws and foibles.

AC: How did you come up with the title?

AL: It's the title of one of the thirteen stories in the book, and it's a story that deals with death and hatred and self-immolation. In the story, the narrator's best friend commits self-immolation in Washington, D.C. and leaves a note that says he hates the Vietnamese communist regime and wants his death to call attention to communist cruelty. But he also leaves his friends back in San Jose, California, reeling from his death. Was it a patriotic act? A passing tourist captures a picture of the man on fire, and the flame reminds the narrator of the bird of paradise - both like a bird and a flame, a phoenix of sorts.

AC: English is your third language, after Vietnamese and French. How is it that you've come to write in English - your "stepmother tongue?"

AL: You know, I have a funny story to tell about English and how I came to fall in love with the language. When I came to the United States in 1975 I was eleven, and within a few months my voice broke. I was desperate to fit in and spoke English all the time. Trouble was, in my household it was a no-no to speak English because somehow it is disrespectful to call parents and grandparents "you" - impersonal pronouns are offensive in Vietnamese. But I couldn't help it. I recited commercials like a parrot and I got yelled at quite often. My older brother one night said, "You speak so much English when you're not supposed to, that's why your vocal chords shattered. Now you sound like a duck." I thought it was true. I went from this sweet-voiced Vietnamese kid who spoke Vietnamese and French to this craggy-voiced teenager. I thought, "Wow, English is like magic." It not only shattered my voice, it changed me physiologically. I believed this for months ... There's magic in the language. I never fell out of the enchantment.

AC: Many of the characters in your stories seem to be preoccupied with time - telling the future ("The Palmist"), being unable to let go of the past ("Bright Clouds Over the Mekong"), living in constant fear of what surprise the present moment might bring ("Step Up and Whistle"). Do you often find yourself writing about characters who struggle in dealing with time?

AL: I hadn't thought of it in that way, but it's true that the past is ever present in the characters' lives in Birds of Paradise Lost. Perhaps it can't be helped. So many of them either experienced trauma - fleeing Vietnam, watching someone be killed - or inherited trauma from those who fled Vietnam, that the past is always flowing into the present. The future is of course the possibility of an absolution, the possibility that they can conquer this haunting aspect of the past so that they can begin to heal. Not all of them do, of course, just like in real life.

AC: What are your thoughts on being identified as a writer of immigrant literature? Given that you've written so much about the Vietnamese diaspora over the past twenty years, how do you think the concept of immigrant literature is changing in the United States?

AL: I think in a larger sense, immigrant narrative is comprehensive and speaks to the core of human experience. Isn't the first story told in the West about the Fall? Adam and Eve were immigrants too from somewhere, a lost Eden, a paradise lost. We all now are so mobile, so nomadic ... That experience of losing home, longing for home, that yearning for meaning and rootedness and identity in a floating world, it's what often makes an immigrant story into an American story ... Today, more people are crossing various borders in order to survive, thrive, change their lives. Even if you don't cross the border, with demographic shifts, the border sometimes crosses you ... America's story is largely an immigrant story. That hasn't changed since the Pilgrims ate their first turkey some four hundred years ago, and they were the original boat people.

AC: As an immigrant, what do you think of the current debate over immigration in this country?

AL: It's unfortunate that the country of immigrants has turned its back on immigrants. The atmosphere after 9/11 is toxic. In the war on terrorism, the immigrant is often the scapegoat. He becomes a kind of insurance policy against the effects of the recession. By blaming him, the pressure valve is regulated in times of crisis ... What we have now is a public mindset of us versus them, and an overall anti-immigrant climate that is both troubling and morally reprehensible. Missing from the national conversation are voices of pro-immigration reformers and civil rights leaders, who can speak on behalf of those who have no voice. Where are the leaders who can speak to the idea that it is not alien to American interests, but very much in our socioeconomic interests - not to mention our spiritual health - to integrate immigrants, that our nation functions best when we welcome newcomers and help them participate fully in our society?

I am glad to see the wheels are moving at last toward comprehensive immigration reform after last year's election. I am glad that immigrants themselves are speaking up. I am hopeful that the pendulum swings toward seeing immigrants in favorable terms once more.

All three of my books, "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and "Birds of Paradise Lost," are immigrant narratives -their dreams, their traumas, their struggles - and I write them with the confidence that these stories, written from the heart, will belong, in time, to America.

Andrew Lam was recently interviewed by Michael Krasney on the National Public Radio (NPR) program, Forum. To listen, click here.

Q&A With Andrew Lam - Hothouse Blog

“When I was eleven years old I did an unforgivable thing: I set my family photos on fire. We were living in Saigon at the time, and as Viet Cong tanks rolled toward the edge of the city, my mother, half-crazed with fear, ordered me to get rid of everything incriminating… When I was done, the memories of three generations had turned into ashes. Only years later in America did I begin to regret the act.” – from “Lost Photos” – October 1997 – Perfume Dreams - by Andrew Lam

Andrew Lam—journalist, essayist, short story writer—reflects on the world in the way only one who has lost his homeland can: with compassion, understanding, and a global stance. His essays, personal and poignant, examine the Vietnamese diaspora and the bridges and barriers between hemispheres, while his story collection defines the idea of exile in completely new ways. Here, in the first installment of this two-part interview, Lam very kindly responds with depth and detail to my questions.

KARIN C. DAVIDSON

Your first languages are Vietnamese and French, and you write in English. It’s not surprising that voice and language play an enormous part in your stories. Do you think your aptitude for these languages carries into your fiction?

Absolutely. I fell in love with the English language, learning it while going through puberty. I am told that children learn foreign languages in the same primal part of the brain as their native tongue, but by high school it becomes a challenge, as brain plasticity has been lost. But in learning a language, your voice breaks, when plasticity is still available and language is both primal and not. That’s how it felt for me. Learning English changed me inside out: I was growing, and my voice broke, and I spoke in a new voice, with a new timbre. It was a kind of enchantment and I never fell out of it.

It helped, of course, to speak Vietnamese and French first. I hear the music in each language, the varying cadences, and the intonations used in different parts of the throat, the mouth, and the nasal area. I can hear voices from many of my characters very clearly – which makes writing short stories like writing plays. And, as an essayist of twenty years, I can hear my own voice very clearly, which makes it less troublesome to write in the third person narrative, that is, when using my own voice for the omniscient viewpoint.

I think I know the answer to this trio of questions, given your travels as a journalist, but readers here might not. And so: Have you ever made a literary pilgrimage? What were your experiences? How did this journey influence your writing?

An interesting set of questions, and the answer to the first is both yes and no. I never intentionally go on literary pilgrimages but have been to places where literature plays a profound role in the experience. Hanoi’s Temple of Literature, for instance, is one of the most beautiful temples I’ve ever visited. Etched on fading tablets atop giant stone turtles are the names of the Mandarins, those of enormous talent and will, who passed the Imperial exams, written as poetry forms, over a thousand years ago. I felt a kinship with these names, for I know the effort to stay awake in late evenings or early morns to write the next sentence, to hear aloud the cadence of your own voice, to get one more line in before darkness takes over.

There are places that remind me of books I’ve read. The Notre Dame de Paris of my childhood brought the memory of reading Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” A promenade on the Thames and a visit to Shakespeare’s theatre, The Globe, made me recall “Prospero” and “Romeo and Juliet,” and imagine myself in the audience when the plays were first staged.

At my literary agent’s home in Boston, I was shown some of his prize treasures: door knobs that once belonged to Somerset Maugham, and, of course, I had to touch them, and felt—at least in my own imagination—their razor’s edge.

In Belgium once, through a chance invitation to a castle, my hostess—a Vietnamese woman married to the baron—prepared pho soup and the aroma perfumed the ancient halls. She gave me Vietnamese books to read. It was strange feeling: to be both at home and in a completely strange setting.

But perhaps nowhere have I found the act of writing more powerful than in the Whitehead Detention center in Hong Kong, where I covered the stories Vietnamese refugees who, at the end of the cold war, were facing forced repatriation. The experience became part of my first book,Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora. But it was there, more than two decades ago, that I witnessed the act of writing as a desperate attempt toward freedom. People who were being sent back to communist Vietnam to an uncertain future wrote and wrote. As papers were hard to get, they told their life stories in tiny words so as to save space on a page. They wrote without having an audience. In the end, many gave me their diaries, their private letters, their testimonies and poetry to take out of the camp. These stories, told as a way to convince the UN of their political prosecution at home, could not be taken back to Vietnam, as they would ironically become evidence that they were “anti-revolutionary.” On the other hand, these writings were not admitted by the UN as evidence of those persecuted in Vietnam. I translated and published a few pieces, but the rest sat for years in my closet, a reminder that for some, refugees and persons who sit in a cell, writing is bleeding.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have been influenced by James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Vladimir Nabokov, Kazuo Ishiguro, Richard Rodriguez, Maxine Hong Kingston, and so many more. I identify with books that I love, and I love these writers for particular books they’ve written.

What is your idea of absolute happiness?

No one asked me this question before, at least, in this particular phrasing. I am not preoccupied with happiness, absolute or partial. It seems to me that it is a conditional state, subject to its opposite, grief and sorrow. Of all these feelings, I’ve had my share. But I will say that for perhaps as long as I can remember, even as a child living in Dalat, Vietnam, my preoccupation is with freedom, in the Buddhist sense. In respect to literature and art, I feel a piece of work has its worth when it, at the deepest level, serves as a spiritual vector to awaken the mind, or to open the gate beyond which opposites loose meanings, and it’s where the Buddha sits, which is to say, the experience of absolute bliss.

This is the second part of an interview with Andrew Lam–journalist, essayist, short story writer.

The first part can be found in the April 3rd Hothouse post,

“Andrew Lam: Language, Memory, Bliss.”

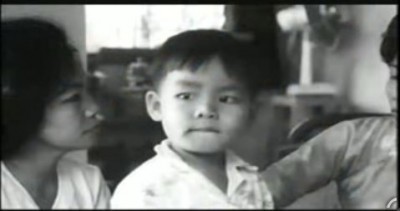

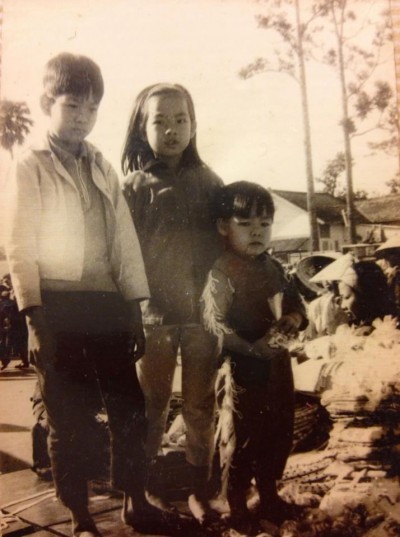

Is there a childhood memory that you return to again and again?

Let me tell you a story. In 2003 a PBS film crew followed me back to Vietnam, and in Dalat, a small city on a high plateau full of pine trees and waterfalls, they coaxed me into revisiting my childhood home. The quaint pinkish villa on top of a hill was now abandoned, its garden overrun with elephant grass and wildflowers.

We broke in through the kitchen and, once inside, I proceeded to explain my past to the camera. “Here’s the living room where I spent my childhood listening to my parents telling ghost stories, and there’s the dining room where my brother and I played ping-pong on the dining table. Beyond is the sunroom where my father spent his early evenings listening to the BBC while sipping his whiskey and soda.”

I went on like this for sometime, until we reached my bedroom upstairs. “Every morning I would wake up and open the windows’ shutters just like this, to let the light in.” When my palm touched the wooden shutter, however, I suddenly stopped talking. I was no longer an American adult narrating his past. The sensation of the wood’s rough, flaked-off paint against my skin felt exactly the same after three decades. Heavy and dampened by the weather, the shutter resisted my initial exertion, but as before, it gave easily if you knew where to push. And I did.

The shutter made a little creaking noise as it swung open to let in the morning air–and with it, a flood of unexpected memories.

I am a Vietnamese child again, preparing for school. I hear my mother’s lilting voice calling from downstairs to hurry up. And I smell again that particular smell of burnt pinewood from the kitchen wafting in the cool air. Outside in my mother’s garden, dawn lights up leaves and roses, and the world pulses with birdsongs. Above all, I feel again that sense of insularity and being sheltered and loved. It’s a sentiment, I am sad to report, that has eluded me since my family and I fled our homeland in haste for a challenging life in America at the end of the war.

Living in California, I had heard much about holistic healing and talk of long-forgotten emotions being stored in various parts of the body; but I had never truly believed this until that moment. Yet, it’s hard for me now to deny that there’s yet another set of memories hidden in the mind, and the way to it is not through language or even the act of imagination, but through the senses.

In America I used to speak of the house with its garden, and my childhood, as a kind of fairy tale, despite the war. Sometimes I would dream of going into the house and taking shelter in it once more; at other times I would dream that nothing had changed, that the life I had left continued on without me and was waiting impatiently for my return. In nightmares I saw it as it was–empty and gutted, and I was a child abandoned within its walls. I would wake up in tears. After so many years in America, I continued in my own way to mourn my loss.

Until, of course, I reentered the house again, and emerged with an unexpected gift–a fragment of my childhood left in an airy room upstairs. Now back in America I feel strangely blessed. I don’t dream of the house in Dalat any longer, or rather when I do, it has changed into another house.

Having touched the place where I used to live once more, I can finally say what I had wanted to say after so many years: Goodbye.

Andrew, your uncle, a singer, who remained in Vietnam after the war ended, talked to you of writing about those who left and those who stayed in Vietnam and of writing with a voice from the heart. Could you speak a little about writing with “a voice from the heart”?

My uncle was a propaganda songwriter for Ho Chi Minh’s army during the Vietnam war, so he belonged to the communist side, the winning side. Now he’s in his 80s, a dissident of sorts, writing about corruption and governmental failures. So he understands deeply about regrets and the need to write and create true art from the heart. He was deprived for years from publishing romantic ballads. His closet is full of songs that have never been sung.

So his advise was very much welcome. He said, “Writing is no joke. You must observe the world keenly and the things that affect you, move you, you must process with your eyes, your head. Then you must find a way to speak with your heart. Because only when you speak from the heart, can you move the hearts of others.”

I understood that long before his advice, but when I heard it, I felt validated. I renewed a deep connection with this estranged uncle–we, the entire clan, all fled to the West, and he was the only one left in Vietnam. I never write from the head–I write about things that move me and hurt me or make me sit up in wonder. My writing is best when they make me laugh or cry or shake my head in happiness with a certain tone, certain turn of phase, as if I am the reader myself. Use your head, your eyes, but yes, always speak from the heart.

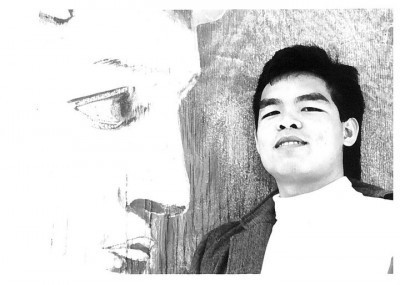

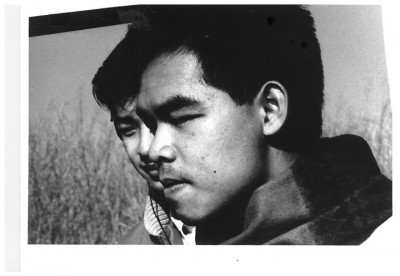

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, East Eats West: Writing in the Two Hemispheres, and most recently Birds of Paradise Lost, his first collection of short stories. Lam is editor and cofounder of New American Media, was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years, and the subject of a 2004 PBS commentary called My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in many newspapers and magazines, from The New York Times to The Nation. He lives in San Francisco.

*

The Poppy: four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis, black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

Karin C. Davidson can also be found at karincdavidson.com.