Q&A With Andrew Lam - Hothouse Blog

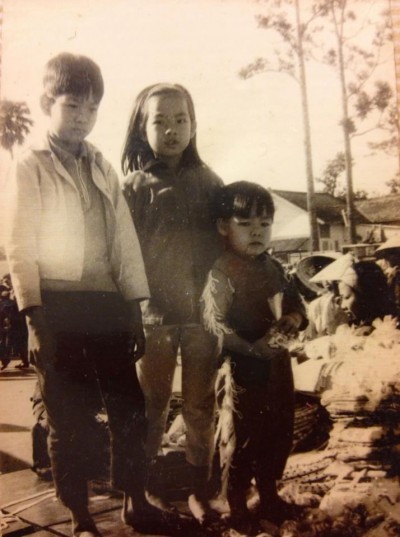

“When I was eleven years old I did an unforgivable thing: I set my family photos on fire. We were living in Saigon at the time, and as Viet Cong tanks rolled toward the edge of the city, my mother, half-crazed with fear, ordered me to get rid of everything incriminating… When I was done, the memories of three generations had turned into ashes. Only years later in America did I begin to regret the act.” – from “Lost Photos” – October 1997 – Perfume Dreams - by Andrew Lam

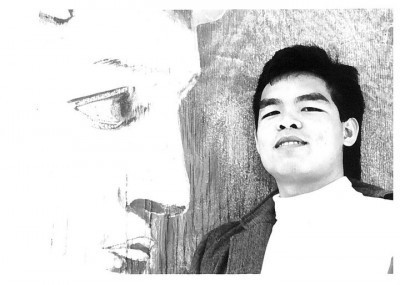

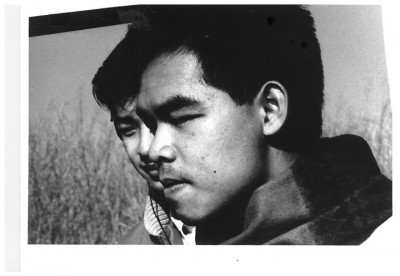

Andrew Lam—journalist, essayist, short story writer—reflects on the world in the way only one who has lost his homeland can: with compassion, understanding, and a global stance. His essays, personal and poignant, examine the Vietnamese diaspora and the bridges and barriers between hemispheres, while his story collection defines the idea of exile in completely new ways. Here, in the first installment of this two-part interview, Lam very kindly responds with depth and detail to my questions.

KARIN C. DAVIDSON

Your first languages are Vietnamese and French, and you write in English. It’s not surprising that voice and language play an enormous part in your stories. Do you think your aptitude for these languages carries into your fiction?

Absolutely. I fell in love with the English language, learning it while going through puberty. I am told that children learn foreign languages in the same primal part of the brain as their native tongue, but by high school it becomes a challenge, as brain plasticity has been lost. But in learning a language, your voice breaks, when plasticity is still available and language is both primal and not. That’s how it felt for me. Learning English changed me inside out: I was growing, and my voice broke, and I spoke in a new voice, with a new timbre. It was a kind of enchantment and I never fell out of it.

It helped, of course, to speak Vietnamese and French first. I hear the music in each language, the varying cadences, and the intonations used in different parts of the throat, the mouth, and the nasal area. I can hear voices from many of my characters very clearly – which makes writing short stories like writing plays. And, as an essayist of twenty years, I can hear my own voice very clearly, which makes it less troublesome to write in the third person narrative, that is, when using my own voice for the omniscient viewpoint.

I think I know the answer to this trio of questions, given your travels as a journalist, but readers here might not. And so: Have you ever made a literary pilgrimage? What were your experiences? How did this journey influence your writing?

An interesting set of questions, and the answer to the first is both yes and no. I never intentionally go on literary pilgrimages but have been to places where literature plays a profound role in the experience. Hanoi’s Temple of Literature, for instance, is one of the most beautiful temples I’ve ever visited. Etched on fading tablets atop giant stone turtles are the names of the Mandarins, those of enormous talent and will, who passed the Imperial exams, written as poetry forms, over a thousand years ago. I felt a kinship with these names, for I know the effort to stay awake in late evenings or early morns to write the next sentence, to hear aloud the cadence of your own voice, to get one more line in before darkness takes over.

There are places that remind me of books I’ve read. The Notre Dame de Paris of my childhood brought the memory of reading Victor Hugo’s “The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.” A promenade on the Thames and a visit to Shakespeare’s theatre, The Globe, made me recall “Prospero” and “Romeo and Juliet,” and imagine myself in the audience when the plays were first staged.

At my literary agent’s home in Boston, I was shown some of his prize treasures: door knobs that once belonged to Somerset Maugham, and, of course, I had to touch them, and felt—at least in my own imagination—their razor’s edge.

In Belgium once, through a chance invitation to a castle, my hostess—a Vietnamese woman married to the baron—prepared pho soup and the aroma perfumed the ancient halls. She gave me Vietnamese books to read. It was strange feeling: to be both at home and in a completely strange setting.

But perhaps nowhere have I found the act of writing more powerful than in the Whitehead Detention center in Hong Kong, where I covered the stories Vietnamese refugees who, at the end of the cold war, were facing forced repatriation. The experience became part of my first book,Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora. But it was there, more than two decades ago, that I witnessed the act of writing as a desperate attempt toward freedom. People who were being sent back to communist Vietnam to an uncertain future wrote and wrote. As papers were hard to get, they told their life stories in tiny words so as to save space on a page. They wrote without having an audience. In the end, many gave me their diaries, their private letters, their testimonies and poetry to take out of the camp. These stories, told as a way to convince the UN of their political prosecution at home, could not be taken back to Vietnam, as they would ironically become evidence that they were “anti-revolutionary.” On the other hand, these writings were not admitted by the UN as evidence of those persecuted in Vietnam. I translated and published a few pieces, but the rest sat for years in my closet, a reminder that for some, refugees and persons who sit in a cell, writing is bleeding.

Who are your favorite writers?

I have been influenced by James Baldwin, Joan Didion, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Vladimir Nabokov, Kazuo Ishiguro, Richard Rodriguez, Maxine Hong Kingston, and so many more. I identify with books that I love, and I love these writers for particular books they’ve written.

What is your idea of absolute happiness?

No one asked me this question before, at least, in this particular phrasing. I am not preoccupied with happiness, absolute or partial. It seems to me that it is a conditional state, subject to its opposite, grief and sorrow. Of all these feelings, I’ve had my share. But I will say that for perhaps as long as I can remember, even as a child living in Dalat, Vietnam, my preoccupation is with freedom, in the Buddhist sense. In respect to literature and art, I feel a piece of work has its worth when it, at the deepest level, serves as a spiritual vector to awaken the mind, or to open the gate beyond which opposites loose meanings, and it’s where the Buddha sits, which is to say, the experience of absolute bliss.

This is the second part of an interview with Andrew Lam–journalist, essayist, short story writer.

The first part can be found in the April 3rd Hothouse post,

“Andrew Lam: Language, Memory, Bliss.”

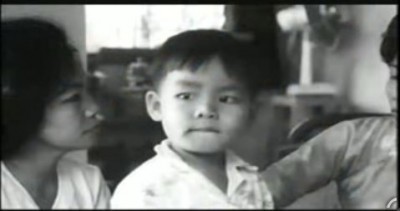

Is there a childhood memory that you return to again and again?

Let me tell you a story. In 2003 a PBS film crew followed me back to Vietnam, and in Dalat, a small city on a high plateau full of pine trees and waterfalls, they coaxed me into revisiting my childhood home. The quaint pinkish villa on top of a hill was now abandoned, its garden overrun with elephant grass and wildflowers.

We broke in through the kitchen and, once inside, I proceeded to explain my past to the camera. “Here’s the living room where I spent my childhood listening to my parents telling ghost stories, and there’s the dining room where my brother and I played ping-pong on the dining table. Beyond is the sunroom where my father spent his early evenings listening to the BBC while sipping his whiskey and soda.”

I went on like this for sometime, until we reached my bedroom upstairs. “Every morning I would wake up and open the windows’ shutters just like this, to let the light in.” When my palm touched the wooden shutter, however, I suddenly stopped talking. I was no longer an American adult narrating his past. The sensation of the wood’s rough, flaked-off paint against my skin felt exactly the same after three decades. Heavy and dampened by the weather, the shutter resisted my initial exertion, but as before, it gave easily if you knew where to push. And I did.

The shutter made a little creaking noise as it swung open to let in the morning air–and with it, a flood of unexpected memories.

I am a Vietnamese child again, preparing for school. I hear my mother’s lilting voice calling from downstairs to hurry up. And I smell again that particular smell of burnt pinewood from the kitchen wafting in the cool air. Outside in my mother’s garden, dawn lights up leaves and roses, and the world pulses with birdsongs. Above all, I feel again that sense of insularity and being sheltered and loved. It’s a sentiment, I am sad to report, that has eluded me since my family and I fled our homeland in haste for a challenging life in America at the end of the war.

Living in California, I had heard much about holistic healing and talk of long-forgotten emotions being stored in various parts of the body; but I had never truly believed this until that moment. Yet, it’s hard for me now to deny that there’s yet another set of memories hidden in the mind, and the way to it is not through language or even the act of imagination, but through the senses.

In America I used to speak of the house with its garden, and my childhood, as a kind of fairy tale, despite the war. Sometimes I would dream of going into the house and taking shelter in it once more; at other times I would dream that nothing had changed, that the life I had left continued on without me and was waiting impatiently for my return. In nightmares I saw it as it was–empty and gutted, and I was a child abandoned within its walls. I would wake up in tears. After so many years in America, I continued in my own way to mourn my loss.

Until, of course, I reentered the house again, and emerged with an unexpected gift–a fragment of my childhood left in an airy room upstairs. Now back in America I feel strangely blessed. I don’t dream of the house in Dalat any longer, or rather when I do, it has changed into another house.

Having touched the place where I used to live once more, I can finally say what I had wanted to say after so many years: Goodbye.

Andrew, your uncle, a singer, who remained in Vietnam after the war ended, talked to you of writing about those who left and those who stayed in Vietnam and of writing with a voice from the heart. Could you speak a little about writing with “a voice from the heart”?

My uncle was a propaganda songwriter for Ho Chi Minh’s army during the Vietnam war, so he belonged to the communist side, the winning side. Now he’s in his 80s, a dissident of sorts, writing about corruption and governmental failures. So he understands deeply about regrets and the need to write and create true art from the heart. He was deprived for years from publishing romantic ballads. His closet is full of songs that have never been sung.

So his advise was very much welcome. He said, “Writing is no joke. You must observe the world keenly and the things that affect you, move you, you must process with your eyes, your head. Then you must find a way to speak with your heart. Because only when you speak from the heart, can you move the hearts of others.”

I understood that long before his advice, but when I heard it, I felt validated. I renewed a deep connection with this estranged uncle–we, the entire clan, all fled to the West, and he was the only one left in Vietnam. I never write from the head–I write about things that move me and hurt me or make me sit up in wonder. My writing is best when they make me laugh or cry or shake my head in happiness with a certain tone, certain turn of phase, as if I am the reader myself. Use your head, your eyes, but yes, always speak from the heart.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

All photographs: permission of Andrew Lam.

Andrew Lam is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, which won the 2006 PEN Open Book Award, East Eats West: Writing in the Two Hemispheres, and most recently Birds of Paradise Lost, his first collection of short stories. Lam is editor and cofounder of New American Media, was a regular commentator on NPR’s All Things Considered for many years, and the subject of a 2004 PBS commentary called My Journey Home. His essays have appeared in many newspapers and magazines, from The New York Times to The Nation. He lives in San Francisco.

*

The Poppy: four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis, black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

Karin C. Davidson can also be found at karincdavidson.com.