Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 68

December 8, 2013

Story of an object

In a previous post, I quoted Edmund de Waal about the stories that objects can “tell” us. In his book, those objects were things made by human beings; the story of the netsuke was not separate from the stories of the people who acquired them. His book did not examine the stories of the people who sculpted the netsuke, as there was no way to trace them that would not have required years of research. A fiction writer or poet might speculate on the possibilities of the lives of the ‘makers,’ however. That is part of what creative writers do.

There are also those “natural” objects that surround us and which can tell stories–or inspire human beings to imagine and tell their stories. For example, every origin myth contains some aspect of telling the story of the earth or sun, stars or mountains, seas, skies, moon.

After some online discussion with artist and writer Deborah Barlow, I considered the story of an object as having tactile and temporal aspects in some cases, and the object as “residue” of an event–or life. Ephemera, correspondence, tokens…many potential stories.

And, of course, works of art. If you follow this blog at all regularly, or check the archives or the Art[s] tab/page, you can tell I think often about art, its stories, artists, and their stories.

For example, a journal or notebook that an artist or writer uses can be a tool, repository, memory-jogger, inspiration-minder, sketchbook, Rolodex…

It occurred to me that my poetry journals, which I’ve been keeping for decades, contain potential stories/poems but are also objects with their own stories to tell–which may or may not be “my” stories, though they necessarily intersect with whatever my story is.

objects, stories

~

Some examples. Tactile, visual, textual.

Inspiration, possibly.

Images captured in several ways.

Necessary–yes. For me.

~

Where do your stories reside? What object or objects seem to require the act of story-making? By which I mean, which objects fire that urge in you?

December 3, 2013

Entitlement, humility, & self-esteem

Among my academic colleagues in the USA, I hear a refrain of grousing about so-called millennial students who, it is averred, perceive themselves as entitled to good grades, exceptions to rules such as number of absences, timeliness, and response to communication, and other “special treatment.” The general criticism goes along the lines of Kenrick Thompson’s letter to the editors of the Chronicle of Higher Education:

… I grew increasingly weary of all the whining, crying, excuse-making, and general lack of attention to responsibility that appear to characterize most of today’s college and university students. I began to sense a growing atmosphere of entitlement among a majority of my students, who apparently believe that society owes them an education. I even endured several instances of students’ insisting they should pass my course simply because they had paid their fees and purchased the required textual materials.

Thompson lays some of the blame for such behavior at the door of college administrators who care more about admission and retention numbers than about the whole package of education, which includes less-measurable outcomes such as personal responsibility and mature problem-solving. The Chronicle has published other essays on related topics, among them these by Elayne Clift and Frank Donohue.

Other critics have blamed Baby Boomer parents for overdoing positive reinforcement so that their offspring do not have to suffer from low self-esteem. These critics suggest the everybody-gets-a-prize approach has watered down the go-get-’em competitiveness formerly considered a hallmark of the individualist American.

The word “entitlement” pops up in a blog post by Toby Woodlief back in 2007, and certainly appeared in conversations I had with colleagues long before that; but there has been much general buzzing that this sense of entitlement is “a Millennial thing.”

What does entitlement really mean? Webster’s has three main entries, the third of which is: “belief that one is deserving of … certain privileges.”

I can therefore say that I believe I am entitled to something, and I can accuse others of feeling that way; but because the word is based upon the subjective sense (“feeling or believing” that one is “deserving of”), can I say for certain that other persons “believe that society owes them an education”? [Note, Thompson does qualify with "apparently".] No one can independently ascertain what another person believes or feels. My students do not tell me they feel entitled to things.

Could this be just a problem of perception or point of view, as so much inter-generational sniping is? Certainly my generation received criticism for its youthful irresponsibility, though it was of a slightly different kind (drop out of the rat race, turn on, be free). Did we feel entitled to ignore the paths our parents took?

I wonder if the real reason older people feel so annoyed with Millenials is the perception that there’s so little humility among the young. Many people my age were raised with the Protestant ethic formula that one should be humble, and humility has long been valued by the Catholic church, as well. Humility is closely allied with shame, however–and even guilt, to some degree (original sin and all that)–giving us neuroses along with our humility. It depends, once again, on your sociological and personal outlook; I am not suggesting that humility is bad or good, nor that entitlement is bad or good. These are just extensions of feelings people have, of personal and subjective perceptions.

Blaming the young people, or blaming their parents, or blaming the culture, for that matter…none of it helps us to understand or to respect one another. And as fellow travelers on the planet, are we not entitled to at least an initial moment of respect?

A balance might be nice.

~

I work with 18-year-olds every day, and I enjoy them. This is not to say that I don’t occasionally wish to wring their necks or boot them out of their warm beds in the morning or remind them that I am not here to make them feel good about themselves for no reason other than their uniqueness. It does not dissuade me from doling out Fs when Fs are deserved (or, shall we say, earned) or reminding them, now and again, that most of their annoyances qualify as first-world inconveniences undeserving of hysterical rants.

I try to keep in mind that they are still learning about the world of other human beings.

In time, if they are mindful and observant and lucky, they should discover that the participation trophy for life is life itself–

IMHO

~

November 26, 2013

Sublime beauty

In his book Survival of the Beautiful, David Rothenberg says perhaps it was the evolution of an abstract aesthetics in art (abstract work as beautiful) that enabled human beings to begin to see natural things as beautiful in themselves–as opposed to the Romantic view that human yearning and elevated sensibility could best be encountered while experiencing Nature or Classicist ideas that found natural things corrupt and irregular, in need of perfection into better-proportioned objectification. In History of Beauty, Eco allows the Romantics their view of the sublime but says that in the late 17th c “the Sublime established itself in an entirely original way, because it concerns the way we feel about nature, and not art.” His text offers the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich as an excellent example, paintings that depict people as observers of the Sublime:

The people are portrayed from behind, in such a way that we must not look at them, but through them, putting ourselves in their place, seeing what they see and sharing their feeling of being negligible elements in the great spectacle of nature…more than portraying nature in a moment of sublimity, the painter has tried to portray (with our collaboration) what we feel on experiencing the Sublime.

I love the idea Eco parenthetically notes here: with the viewer’s collaboration. These paintings permit us to enter into the experience as the great preponderance of the artistic canon did not. Some critics suggest the environmental “movement” (in the USA, at least) owes its lineage to Leopold via Thoreau through Darwin, Wordsworth, and the German Romantics.

Friedrich’s work tends a bit over the top for my personal tastes, but I do think some of his best work (notably The Wanderer above the Mists, Woman on the Beach of Rugen, Moonrise by the Sea) does exemplify a sense I have experienced myself in natural surroundings when I feel myself a “negligible element” amid the remarkable scope of the cosmos and the world.

In the USA, at about the same time as the German Romantics, the paintings of the Hudson River school evoke some of the same sense of nature-as-sublime. (Frankly, I prefer Thomas Cole to Friedrich.)

~

This, too:

“The sense of the Sublime is a mixed emotion. It is composed of a sense of sorrow whose extreme expression is manifested as a shudder, and a feeling of joy that can mount to rapturous enthusiasm…while it is not actually pleasure…” Friedrich von Schiller, On the Sublime (tr. Alastair McEwen)

~

“Poetry might be defined as the clear expression of mixed feelings.” I am pretty sure W.H. Auden said that. Which, by the way, gets us into the territory of the Sublime as described by Schiller.

~

In Japan, in the 17th century, Matsuo Basho composed haiku, some of which demonstrate the sense of the Sublime (without being Romantic at all)–i.e. that sense of rapture tinged with the shudder of grief or the feeling of awareness of one’s negligibility:

A wild sea-

in the distance over Sado

the Milky Way.

~

I stand on my back porch; I am small and negligible, the sky is large and Sublime.

November 24, 2013

Tai chi [crane pose]

A memory of my undergraduate days: I was wrestling with indecisiveness, both academic and personal, and consulted a professor who sometimes acted as a sounding board for me. What should I do? Here was one option, here another, no way to decide how best to proceed. I felt mired in uncertainties.

She listened compassionately to my dithering and then replied by telling me about a Buddhist saying: “When leaning left, lean left. When leaning right, lean right. When wobbling, wobble.”

I felt relieved. All my life, I had been criticized for my indecisiveness; here was a person who allowed me to accept it as another way of being. There was also the implication that I would not be wobbly forever. Eventually I would bear enough in one direction to proceed. Meanwhile, I was granted a kind of grace–a moment of compassion for my wobbly state of being–and all I need do was to wobble mindfully.

[Admission: I have never been able to confirm that this actually is a Buddhist saying, or for that matter a Taoist or Confucian saying, and I think perhaps she invented it.]

~

I recovered the memory above while trying a move in my rather new practice of tai chi.

I recovered the memory above while trying a move in my rather new practice of tai chi.

One may infer that I am less than steady on my feet, particularly when required to stand on one foot, as necessary for “crane” position in the tai chi form I am learning. So, I try to be mindful of breathing while attempting crane. And I wobble, but I try to wobble slowly and mindfully.

I am, however, fairly good at leaning. Standing on both feet while placing my body’s weight on one leg comes naturally to me, whereas the groundedness of the horse stance takes more concentration.

“When leaning, lean.” I can do that.

~

Once again, as per my last post, establishing that middle way–though it is not easy, and it is not hard–doesn’t come naturally, especially when I feel spread a bit thin in other areas of my daily life.

Therefore: “When wobbling, wobble.”

~

From KHHuber’s blog, here’s a lovely photo of (egret? crane? white heron?) steadily elegant on one leg:

kmhubersblog.wordpress.com Photo KM Huber

If only…

November 20, 2013

The poet & the Good

I have recently finished reading Robert Archambeau‘s collection of essays The Poet Resigns and am mulling over the idea of resigning with him.

It’s not that I necessarily want to give up writing poetry but that, in my reflections about where I can do the most good among the community of sentient beings, my work as tutor and teacher almost certainly has an effect both deeper and broader than my work as poet. This “good” hearkens to the ancient Good of Socrates, Plato, and their ilk but also to the sense of mindful “middle way” of the Tao: a practical path between two values that may be incompatible in many ways.

~

The readership for contemporary poetry is small, and my readers number only in the hundreds; among those readers, resonance of any kind–aesthetic, emotional, lyrical–is likely to be limited to a small number of poems. A poem of mine that effects some measure of The Good upon readers represents a minuscule good moving into the world. The net effect, I imagine, hardly registers…not that net effect matters so much. I suppose if a poem of mine moves just one person enough to evince even a small transformation, something has been achieved beyond my individual abilities in the composition of that particular piece.

The readership for contemporary poetry is small, and my readers number only in the hundreds; among those readers, resonance of any kind–aesthetic, emotional, lyrical–is likely to be limited to a small number of poems. A poem of mine that effects some measure of The Good upon readers represents a minuscule good moving into the world. The net effect, I imagine, hardly registers…not that net effect matters so much. I suppose if a poem of mine moves just one person enough to evince even a small transformation, something has been achieved beyond my individual abilities in the composition of that particular piece.

As a teacher and tutor for the past ten years, my role expands not merely to number of people encountered (few of whom will remember me as an individual) but to the concepts I present to them, most of which will be significant in their lives one way or another–although not immediately, and probably unconsciously. Lately I have been devoting more of my limited energies to this aspect of my life work. Such focus does impede my ability to do creative work of other sorts.

~

This bust resides in the Louvre, and was found here: http://www.humanjourney.us/greece3.html

Example: I am reading a little book on philosophy for beginners by Thomas Nagel. The Nagel book is on my table because I have been trying to find simpler ways to talk with students about their philosophy essays. While my main enterprise as writing tutor is to help students to clarify and correct their mechanical weaknesses (sentence and paper structures), it is not always possible to ignore content weaknesses; a student can write correctly about nothing of value–and receive a D or, in the case of Philosophy classes especially, an F.

But understanding philosophy is important.

Now, it is often extremely difficult for beginning writers to express their understanding of philosophical concepts in writing. They are just learning rhetoric and fall into fallacy errors through grammar as often as through thinking. Since I am not supposed to be a content tutor, I have to find ways to tease out what the student understands (or does not understand) and make that idea come through clearly on the page.

Kind of like mind-reading.

[Aside: I have to admit this can take a lot out of me by the end of the day.]

The Nagel book is one of several philosophy primers I have been reviewing to try to find a text to which I can refer my more confused students, the ones who cannot infer the basics from their professors’ lectures or assigned readings. There are academics who might suggest such students do not belong in college in the first place; but I believe in the ideal of an educated populace, and whether or not these students stay in the university through graduation, they can benefit from the discipline of thinking about thinking.

It feels rewarding when, after half an hour of discussion and writing coaching, a young person leaves my office slightly more enlightened. So they tell me, anyway. I know from experience that writing about something helps a person to understand not only the subject but, more importantly, what the writer thinks about the subject.

~

So perhaps my creative energy is better served in the direction of others through tutoring than through poetry; perhaps the former leans more toward the Good. Perhaps I am a better tutor than poet; this is indeed likely, although I have been poet-ing longer than I have been teaching. Then again, not to knock the art of teaching, but writing poetry is much more difficult than the teaching I do. And I get paid to enlighten people through my tutoring.

Not so through poetry. Indeed, Mr. Archambeau–you have gotten me seriously to think about tendering my resignation as a poet, though not without considerably more reflection on the possibility. Writing about the idea has helped me to understand where the Good fits into all of this, and what the middle way might be.

Now, I suppose I could write a poem about the subject…

~

November 15, 2013

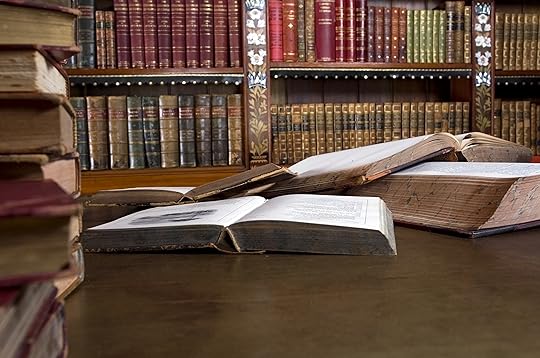

Autodidact as adult student: Goddard & me

In a previous post, I mentioned my peculiar undergraduate experiences at alternative institutes of higher education (The New School) and how being a book-loving autodidact influenced, perhaps even configured, my approach to education. My favored learning strategies led me to a non-traditional graduate school program, as well. Reflecting upon my higher education, I realize that every institution I attended chose alternatives to standard pedagogy–and I am grateful that such colleges exist. The world needs outliers.

A kind of heaven.

The New School’s pedagogy for the “Freshman Year Program” was seminar-based. That worked very well for me. Classes were small, discussion-centered, predicated on the reading of significant original texts–no textbooks. The professor was not a lecturer but a participant-coach and mentor.

The program was only a year long, however, so I had to transfer. There were a number of experimental college programs in the 1960s and 1970s; without the miracle of internet searching, however, they were not easy to locate. I did not find out about St. John’s College, Reed, or Evergreen, for example. I stumbled instead upon Thomas Jefferson College (now defunct) in Michigan.

I completed my undergraduate studies without ever seeing a syllabus. Yet I read more books than the majority of my standard-pedagogy-educated peers and discussed classic and contemporary texts, science and history and literature, in depth with my peers and with scholars. I wrote a lot and did hands-on projects, independent studies, experiments and interviews. TJC drew criticism for its ‘flakiness’ and ‘lack of oversight,’ (some of which, I can attest, was deserved); however, the former college president “described TJC as perhaps too far from the mainstream, but attracting excellent students, noting that ‘Thomas Jefferson College…was sending a larger percentage to graduate school than the College of Arts and Sciences.’” Yes, but in my case it took awhile to get there.

Much water under the proverbial bridge: suffice it to say that in 2000, I returned to college to pursue a masters degree…and I wanted to learn in the kind of environment that suited my style. There were other factors then, as well: two children, for example, and responsibilities I had not encountered as an undergrad. On the other hand, by 2000 I was an adult and more motivated and disciplined than I could ever have been at age 19.

I chose Goddard College for a number of reasons, foremost its small seminar-style instruction, its mix of workshops and instruction, its focus on readings, annotations, mentoring, and community-building among students and faculty–reaching outward into the world at large. The low-residency format only works if the student is independent and self-directed, which–as a returning, “adult” student–I certainly was. I appreciated the school’s more interdisciplinary approach to the creative writing program. We didn’t have to face off, pegging ourselves as poets or fiction writers. And creative non-fiction was taken seriously as a genre to develop voice, style, and depth…it could be studied and parsed. That endeavor of interdisciplinary arts education is true of a few institutions now but was rather new among MFA programs in the late 1990s.

Another college without core requirements, without syllabi, without standard formats. But, like New School and TJC, Goddard offers excellent professors dedicated to students’ intellectual enrichment and personal transformation, small-group discussions, and narrative evaluations. I knew how to balance life’s responsibilities when I enrolled, and I knew what kind of teaching I’d respond best to. How did I learn that? See above. Suits my philosophical, bookwormish, autodidactic approach to–well, practically everything!

November 7, 2013

Abstraction, evolution, & sky-beauty

I awakened this morning to a sunrise of surpassing beauty. As I drove to work, I remembered that the first poems I recall ever writing were about the wind and about dawn–perhaps I wrote other poems as a child, but these two are the only ones I remember: poems that celebrated something I found lovely in nature.

After the vivid morning sky, we had a day of rain; and on my commute home, a compelling sunset bookended the working day. I call these skies “beautiful” and would definitely regard my experience of looking at them as aesthetic.

And yet, it’s only the sky, some clouds, the sun, phenomena that science has explained. What makes it beautiful?

photo: Beejay Grob (North Carolina coastal sky)

David Rothenberg’s 2011 book Survival of the Beautiful: Art, Science, and Evolution has accompanied me for the past week; I have been reading it when I can find time to read and to cogitate. Rothenberg speaks directly to the question of what makes us experience beauty, whether beauty is a human-only construct, and from where the qualities of aesthetic experience arise. He explores among other things whether beauty (especially in the form of art) evolved along with us, what makes it timeless (if it is indeed timeless), and whether our grounding in nature as earthly beings formed the grounding for what we deem beautiful.

And he considers symmetry and biology and abstract art and math and music. There’s quite a good deal of synthesis and speculation going on in this book.

~

Rothenberg writes that he is interested in whether humans’ developing education in abstractions–concepts and abstract arts–might produce an outcome that increases our appreciation of things in nature and the cosmos. He writes:

It might seem this century has freed us from interest in any kind of constricting form or function in art, but I want to test out a different theory: that abstraction in the arts has made us find more possible beauty in the natural world…as art exalts pure form and shape, the laws of symmetry and chaos found in mathematics and science seem ever more directly inspirational. Aesthetically, we become more prepared to see beauty where before we saw only the clues of beauty, its glimmers or possibilities…our minds are more attentive to an abstract kind of beauty that we can discover but not necessarily build or create.

It takes him several chapters to braid together the many strings of his interdisciplinary inquiries; but the upshot is that while I feel he does not answer the questions he begins with, he does deepen the reader’s thought process about art, beauty, and the evolution of ideas as well as of organisms. He says the interesting discussion lies not with what is or is not art, nor how to evaluate the individual merit of works, but rather “how artistic expression changes how we think in ways only art can accomplish.”

~

In light of Rothenberg’s musings on how natural-feeling abstract art can be, here are some examples: Barlow, Ellis, (contemporary) and Klee (modern).

Rothenberg concludes with some ambiguity about aesthetics and evolution, which suits his book-length and life-long explorations on the interweavings of these ideas; but he adds with certainty that “[b]iology is not here to explain away all that we love in terms of the practical and rational. That is not how nature works. Nor should we shrink from our natural astonishment at the magnificence evolution has produced.”

~

He mentions John Cage’s work and approach to composing, and I think Cage’s main point in so much of his work is getting us to listen, to see, getting us to be attentive. Viz Rothenberg’s words quoted above, maybe an integration of abstraction does open us to be more attentive to the beauty that exists in the world without any artist making it. We could not, in the past, have appreciated the fractal values of river deltas viewed from airplanes; and perhaps only natural (or trained) artists noticed how the twigs of a tree reiterate the shapes, angles, and curves of the branches, boughs, sometimes even bark. Now we know about Mandelbrot sets and fractal geometry, and those abstractions can generate beautiful patterns. Now we know the Fibonacci sequence of numbers–an abstraction–appears in snail shells and sunflower seed-heads.

We do not have to be mathematicians, chemists, art critics, environmental scientists, physicists, sculptors, violinists, composers, dancers, college professors or biologists to recognize patterns and symmetries, or to find that slight variations in the pattern enhance the experience through the kind of surprise and delight that I discover in great poems.

We just have to be attentive.

~

November 3, 2013

Irritation, explanation, interpretation

I had another testy conversation about poetry analysis recently. Hence, this brief explanation, rationale, and license to interpret.

Feeling a mild irritation…

I truly sympathize with people who prefer to avoid any sort of literary analysis; so many times, it is such a badly-taught subject. Nevertheless, it is never a good idea to refuse to learn about something thanks to one or two negative experiences. If that were the case, no one would ever learn to walk (we fell down, we cried, we refused ever to rise up and take another step).

First, let go of the idea that the purpose of literary analysis is to understand exactly what the writer meant. Second, let go of the idea that poetry contains a symbolic hidden meaning.

Instead, recognize the following fairly obvious observations:

1] the poet wrote what he or she meant; the reader can interpret on the reader’s terms.

2] the meaning is in the poem itself.

Poetry is a form of communication, and it is not a detective story. The poet said what he or she said because the poet determined that was the best way to communicate the experience.

Problem: You, the reader, fail to understand the poem. All that means is that you and the poet may be speaking in different terms and that, to you, the poet’s determination of the best way to say what he or she meant does not convey much. Welcome to the world of human interactions.

The reader has choices: turn the page, for example, and ignore the poem. Or read the poem and find its sound or rhythm entertaining. Or read the poem for its summary–the top-line story, if there is one. Or relish the poem’s mood or use of language. Or its images.

Or throw the poem across the room in frustration or anger. Poetry is powerful enough to evoke such responses.

You could also try to examine the poem, look at how the poet uses rhythm or sound or language or image or metaphor or rhyme…you might learn something about how a writer puts a poem together; and even if you do not manage to shoo the “real meaning” out from under a chair, you may be able to come to terms with the poem in your own way.

You are permitted to interpret what the poem means for you.*

~

*CAVEAT: This approach may not get you an A on your analysis paper (though it might), but it will serve to enhance your lifelong appreciation of the poetic art.

October 29, 2013

Trees & tombs

On a brisk and clear autumn day, I visited Brooklyn’s magnificent and park-like Green-Wood Cemetery. Established in 1838, the burial grounds were planned as a gently-rolling landscape of hills, winding paths, ponds, and specimen trees in what was then rural Long Island. The “History” tab of the National Historic Site’s webpage says:

By 1860, Green-Wood was attracting 500,000 visitors a year, rivaling Niagara Falls as the country’s greatest tourist attraction. Crowds flocked to Green-Wood to enjoy family outings, carriage rides and sculpture viewing in the finest of first generation American landscapes. Green-Wood’s popularity helped inspire the creation of public parks, including New York City’s Central and Prospect Parks.

These days, US citizens feel far less connected to death, and the concept of picnicking among gravesites may seem creepy. The organization devoted to keeping up the cemetery as a historic site (it is, by the way, still an active cemetery) offers tours: visitors can tour the catacombs, visit graves of famous people, take an architectural monument & mausoleum tour, and see the sculptural highlights of the cemetery.

The sculptures are largely figural pieces and tend toward the Gothic sentimentality of the late 19th century: draped urns, weeping maidens wearing Greek chitons, triumphant angels, busts and full-length portraiture, columns and more columns (Corinthian being far and away the favorite). If such monuments appeal to you, Green-Wood is decidedly worth a visit; it is also a favorite among history buffs. A Revolutionary battle was fought on those grounds, and there are some early graves from the Dutch pre-Colonial era, not to mention the inherent historical interest of a major city mortuary established in the 1830s.

Here’s a flickr site devoted to images of Green-Wood.

~

While history and art interest me a great deal, what most arrested my attention at Green-Wood were the trees. Seldom do I get to see dozens of 170-year-old oaks, 100-year-old weeping beeches draping their boughs over paths and tombstones, large female gingko trees that drop their smelly orange fruits on the ground, old elms that survived Dutch elm disease, enormous cedars and firs of every description, majestic walnut trees (the woodlot at my house sports only some weedy black walnuts). Three tall, long-armed people embraced the circumference of one of these old oaks…

Loving up the trees at Green-Wood.

~

There are hundreds of species of trees at Green-Wood, aptly named; and in fall the colors are handsome. I can imagine the pastel colors of the flowering trees there in spring!

So I think of the place of the dead as a fantastic terrarium of living things encased in city streets, a bubble of micro-environment–470+ acres–wherein thrive trees, a wide variety of birds, ornamental grasses and flowers, shrubs (too many hydrangeas, perhaps), squirrels and, judging by the dug-up divots evident in grassy areas, skunks, opossums, and possibly raccoons.

And yes, I recognize that cemeteries have a reputation for good soil because the plants are “fertilized” by human remains–undeserved reputation in modern times due to sanitation requirements and at Green-Wood, where many of the interred are not even in the ground. Even if and when human decay complements the soil nutrients, the idea doesn’t bother me. I am enough of a scientist, and enough of a Buddhist, to appreciate the biocycle.

October 27, 2013

Objects and stories

I’ve been occupied with many things lately that take me away from blogging and even from poetry. I have been re-reading Hard Times which seems, suddenly, relevant and appropriate to life. I deeply value my world of the imagination, which is not bi-modal, black-and-white, straight facts, simple storyline, no diversions. It is rich and complex and worthy of exploration. It is mysterious and loving and paradoxical, a puzzle and a joyful muddle and a pool of sorrows. It loves to divulge and elaborate and dwells in velvety ambiguities.

I post herein a quote not from Dickens, however, but from Edmund deWaal’s book The Hare with Amber Eyes–in hopes that it will jog my memory for a further post on this topic eventually.

…

“It is not just things that carry stories with them. Stories are a kind of thing, too. Stories and objects share something, a patina….perhaps patina is a process of rubbing back so that the essential is revealed, the way that a striated stone tumbled in a river feels irreducible, the way that this netsuke of a fox has become more than a memory of a nose and a tail. But it also seems additive, in the way that a piece of oak furniture gains over years and years of polishing…

You take an object from your pocket and put it down in front of you and you start. You begin to tell a story.”

…

Or something that is not in your pocket. Something you may see along the road, on a path in a park or forest, reflected in a window. The story, perhaps, of a story you thought you knew well–one your father told you, which his father told him, and to which there is truth but also layers and about which you may be able to weave another tale.