Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 81

April 21, 2012

Reverie

“The image can only be studied through the image, by dreaming images as they gather in reverie.” ~Gaston Bachelard

I’m immersed in Bachelard’s The Poetics of Reverie, which has a subtitle I adore: “Childhood, Language, and the Cosmos.” In the book’s first section, however, I felt myself a bit bogged down because the reverie of words (language) he describes deals with word gender. That works for French, and for most languages [or so I understand], but not for English.

Initially, then, I found myself wondering why I was reading the text. But I like Bachelard’s style, enthusiastic and looping and always replete with inquiry upon inquiry; and I love his dedication to and defense of poetry. Not all philosophers have been so kind to poetry.

As I was driving to work one morning, however, I found myself dwelling upon the above chapter about the reveries words can inspire. I fell into a recollection of myself as a very young child, the way I loved to peruse the dictionary. Even before I could read, the heavy tome with its onion-skin pages and glossy color plates of the flags of the world or of gemstones appealed to me as a room in which to become lost, a forest of leaves in which to cover myself or to lie upon, a river of language in which to be immersed. When I was older and a more capable reader, I browsed the examples, the multiple meanings and uses, the parts of speech and the etymologies of the words.

Bachelard, I realized, is correct. The contemplation of words themselves leads to reverie, to thinking about thinking, to making dreamlike concatenations that chug through the consciousness and lead to imagination. His example involves contemplations and imaginings about the genders of words and how they suggest all kinds of interweavings and reactions, but noun gender need not be the motivating inspiration. For me, etymology accomplishes the same ends.

Contemporary adult life offers few chances for reverie. My commute to work is often the only time during the week when I can daydream a bit. My best opportunities for reverie are during a walk outside or while gardening, but I don’t get to do those things every day. I agree that reverie or daydream leads, very often, to poetry or to philosophical innovation or understanding; and Bachelard’s initial chapter on the rambling, amusing, aimless process of reverie makes me wish to go back to my childhood days of less responsibility and more imagination. Of course, that is impossible, but of course, that is part of what the philosopher intends (there is a later chapter on childhood reverie…I will be reading that pretty soon).

Boredom invites reverie. Who, in these busy times, with the many entertainments we carry in our pockets, is ever bored? So many of us, when bored, simply turn off the iPhone or the TV and sleep.

“It is a poor reverie which invites a nap.” ~Gaston Bachelard

My upcoming musings on this book will probably include garden reveries. Or memoir. Or etymology. Who can tell?

April 20, 2012

Haiku impressions

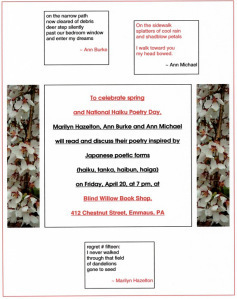

The reading Friday at Blind Willow Bookshop, a lovely used bookstore specializing in literature and unusual or rare books, combined the voices and perspectives of three poets who are exploring Japanese poetic forms.

Here’s a summation of my own remarks, though Marilyn Hazelton and Ann Burke had much to share. I’m not including the poems we read, either–Ann Burke’s haiga-like tanka poems coupled with art work or photos were lovely, though, and I wish I had files to post. Marilyn included work from the tanka journal she edits, red lights.

~

I learned about the haiku form long ago, but I can’t remember exactly when. I think it may have been during my junior high school years, though I certainly didn’t learn it in school—there was no poetry taught at my schools. I was exposed to poetry through other means: church, nursery rhymes, my own reading, relatives, song lyrics.

Initially I learned the syllabic approach, 5-7-5 syllables in English. That is the way the form was taught in the USA the 1970s. And it was clear to me early on that haiku is visual or physically-based; the imagery is sensual and real—in other words, what is in the world is in haiku, and vice versa. So it is not imaginative in the sense of fiction or dream. It engages the imagination in other ways, which means the poet has to corral quite a bit of compressed and specific imagination into a few words. The intense compression of these brief forms requires the poet to work hard at expression through the tightest possible means in language without employing what we in the Western traditions term symbolism. Classic Chinese poems often used symbolism, but Japanese poems relied more on allusions of several types (historical, poetic, seasonal). We tend to term these “symbols” (ie, cherry blossom equals spring romance) but that is not actually an accurate way to define the way concrete imagery is used in Japanese poems.

Later, after more study, I learned some details and contexts for the seasonal allusion, the references to previous poets or poems, the cutting word, the reasons haiku in English may need to be briefer than 17 syllables for maximum effect; and I found out about related forms of Japanese poetry such as haibun, renga, tanka. I met Marilyn Hazelton and learned through her, as she studied and taught the forms, in English, to other aspiring writers. Japanese poetry forms may seem to follow arbitrary rules, but that is no more true than asserting that western sonnet forms follow arbitrary rules.

My study of this poetry brought me a better understanding of the Imagist poets of the early 20th century in the sense of how they were influenced by, and how they misinterpreted, the haiku poem, crafting in the process some critically important poems for western readers. Poetry is a marvelously flexible art, elastic and willing to morph as its authors are willing to experiment. I think of much of my work as based in a ‘haiku moment’ for inspiration or image.

I will be the first to assert that haiku is not my métier, nor is tanka form. My poetry—and I’ve written a great deal of it—is generally more Western in style and tone, no surprise given my cultural and educational background. Yet haiku appealed to me immediately because, I think, of my interest in visual art and in the natural world.

My attraction to haiku is therefore image-based. My interest in Japanese poetry also increased after I studied Zen. The two are inter-related, also no surprise. In my notebooks, and on random pieces of paper I use to jot down ideas for poems, nine times out of ten the phrases I want to capture are physical images. Later, I may try to craft these jottings into a haiku. More often, they get employed as lines in other types of poems.

Sometimes, a poem I attempt to write as haiku becomes a tanka…or a longer poem in some other form (free verse, blank verse, etc.); in any case, the sensual first impression is usually what I first observe and note. My own interest in nature and my physical environment make haiku-type poetry sort of an inclination. So the inspirations and influences for me include Zen, visual art, physical or concrete imagery, nature and season, brief observation, compressed or concise language use, and a quality of universality in the poem.

~

For writers who have done Westerners the service of exploring, interpreting, and explicating haiku and the Zen practice that leads to the haiku moment, I suggest Jane Hirshfield, Robert Aitken, William Higginson, Penny Harter, Hasegawa Kai, Earl Miner, Richard Wright, Gary Snyder.

April 18, 2012

Another poetry event

To anyone living in the Lehigh Valley area of Pennsylvania, a reminder about my two upcoming readings–one this Friday (April 20, free, at Blind Willow Bookshop) and one on Sunday the 29th. The event on the 29th is a fundraiser for the Lehigh Valley Arts Council, so there is a $10 fee.

Details are on my Events page.

This weekend, after the bookshop event, I plan to post a recap here. Meanwhile, enjoy the blossoms of springtime.

photo: Ann E. Michael

April 12, 2012

Passion, art, doubt

“We work in the dark–we do what we can–we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion, and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.” ~Henry James

Azar Nafisi cites this James quote in Reading Lolita in Tehran. In her memoir-based ruminations on James, she identifies deeply with James’ ambiguity, a trait in James’ fiction that her Iranian students find complex and difficult. She spends a couple of pages examining the problematic aspects of James’ work that frustrate and puzzle her students even as the same aspects appeal to her. She likes the doubt.

This quote, with its passionate appeal to the task of art, and its uncertainty, likewise resonates for me. My encounters with the ambiguity inherent in art stem from a set of experiences very different from Nafisi’s, and from James’. But our passions are similar in intensity, although I would probably tone down James’ phrase “the madness of art.”

Where did the doubt and the passionate need to make a task of art begin? I can probably come up with dozens of possible answers for myself. I’ll mention just one right now, the way I learned to feel about visual art. A framed print of the painting shown here [The Adoration of the Magi, by Fra Angelico and Lippo Lippi] hung on the wall when I was very young. It was the most fascinating object in the house. I spent what seemed like hours gazing at its details, finding the animals among the throngs of people, old men and young women with their hair in roped braids, children and peasants and half-naked lepers amid the ruins. I knew the story well, but the way it was told in this painting engaged me more completely than any other way I’d absorbed the Christmas narrative. And it was round! It was the only round picture I’d ever seen.

A framed print of the painting shown here [The Adoration of the Magi, by Fra Angelico and Lippo Lippi] hung on the wall when I was very young. It was the most fascinating object in the house. I spent what seemed like hours gazing at its details, finding the animals among the throngs of people, old men and young women with their hair in roped braids, children and peasants and half-naked lepers amid the ruins. I knew the story well, but the way it was told in this painting engaged me more completely than any other way I’d absorbed the Christmas narrative. And it was round! It was the only round picture I’d ever seen.

This Adoration moved me, even though I was only six years old. The idealized, pastel paintings of Jesus that hung in the Sunday school rooms were bland and static by comparison; they did not make me want to love the pretty man in the clean robes. But this painting! Even the peacocks adored the Baby Jesus. And yet the picture contained more than adoration and joy. Pain was implicated–the beggars, the cripples–decay was there in the broken-down building. Horses stamped impatiently; some of the people turned away. The whole thing was full of tension and human frailty and doubt as well as gladness.

It strikes me, now, that doubt is one of our tasks; for it is through uncertainty, curiosity, mild skepticism, and a willingness to weather the problems and puzzles of ambiguity that we keep alive our passion for the task of art, to make new, to express, to challenge, and to celebrate. That is what the devoted students in Nafisi’s book manage to cling to as they read “dangerous” books in Tehran. And that’s perhaps what Henry James meant when he stated that we work in the dark.

If the madness of art exerts itself through the tasks, the doubt, and the passionate devotion to doing what we can–well, I can live with that.

April 10, 2012

Chapbook review

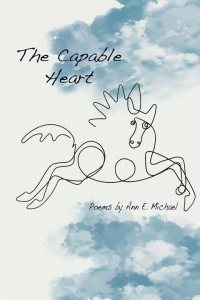

I was away for a few days…and while I was in North Carolina's Blue Ridge Mountains, Dave Bonta posted a nice review of my last chapbook, The Capable Heart, at his site vianegativa.

Thanks, Dave!

A longer posting of my own should appear here in a few days, after I have readjusted to the lower altitude of my Pennsylvania valley.

April 1, 2012

Water thoughts

This weekend brought some rain to our valley. Gratitude! The rain softened the soil and the air, bringing haze and drizzle and greening up the parched grasses. Nonetheless, a little searching of weather-history sites revealed that this March was the fourth-driest on record, with only .92 inches of precipitation; the average precipitation is 3.4 inches. The region is also 4″ below average for the first quarter of 2012. As a gardener, I take my "stewardship" of the earth and its resources seriously; and water is one of the most valuable resources that we take for granted here in the United States. I can conserve water at home through many means–and I have established fairly resilient plants in my ornamental gardens (if it survives drought and flood and the deer don't eat it, I find a way to make it look pretty in the yard). There isn't anything I can do to change the weather patterns, though.

Given my deep concerns about cyclical drought, long-term equitable distribution of water, potable water and clean waterways, I thought I would use this post to share the title poem of my upcoming collection, Water-Rites. The publishers at Brick Road Poetry Press will be bringing the book out this spring. If the year continues to be a dry one, then it's strangely suitable for this particular collection: I wrote many of these poems during a serious drought cycle. Some of the poems deal with the loss of a close friend, too. For me, drought and grief are metaphorically closer than "floods of tears." Loss felt more like the numb, dry absence of drought than like the gift of rain.

For some soothing photos of running natural waters, I recommend Don Schroder's series taken at Rickett's Glen. Meanwhile, I'm grateful for the rain.

Water-Rites

I.

I take my shower

lean into water's hot stream

too many minutes

lathered in steam, guilty skin,

greedy pores

knowing the well empties

and the earth's in drought.

II.

Off Nova Scotia's south coast,

small islands spring fresh water

surrounded by sea. We hauled

the pine-brown but potable

stuff from the well in buckets,

heated it on the woodstove,

dabbed at our bodies, and dried

in the sea wind. We drank it:

pine-water coffee—water

sprung from nowhere, gift of rocks,

glaciers, lost to eons.

III.

The Mideast erupts again.

Retribution. Religion. Water-rights.

Oil will get you water;

water will buy you oil.

Barrels and tanks,

tanks and barrels—

each has a meaning

for water and warfare.

I reach for soap.

IV.

On the Caribbean volcanic island,

rain's the only source. Rock

carved into cisterns. Water

hauled in like gasoline, by truck.

V.

We do not need to be so clean.

The industry of soap cajoles us—

promoting glycerin, methyl paraben

and the lauryl sulfates—

exposes our filth and offers

deliverance from evil.

Lye and tallow. Better to wallow.

The cost is less. Think:

Were we not formed of clay?

VI.

Tap

like sap

provides

sustenance.

Water

up root and

down:

taproot.

Soil unsoiled

needs rain

silt sand loess—

water-loss

water's

lost,

VII.

runs down my body,

thirsty skin, down drain

into pipes, tanks, drainage field

where ryegrass covers meadow,

percolates through sand, loam; disperses—

if it should rain

I will run out, arms wide,

mea culpa, mea culpa,

so many parched human beings

desiccating earth and I—

I thought to wash

my trespasses away

in something other

than rain.

© 2012 Ann E. Michael

March 29, 2012

Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Rich has died at 82, a long life for a person who dealt with a chronic and often debilitating condition (rheumatoid arthritis). Physically small and often frail-looking–almost elfin–her appearance and her personal modesty belied her strength, influence, assertiveness. She influenced poets and feminists, women and men, and challenged the social norms in many ways. I discovered her work in the 1970s in a women's literature class at college, and her thinking as well as her writing enriched my view of the world.

Rather than try to collect my own thoughts about this poet, essayist, and influential human being, I'm going to post some links to others who have done so. I'll update as the week goes on.

Here's a videopoem of "Diving Into the Wreck." Thanks to Dave Bonta for pointing me to this film.

http://www.midwayjournal.com/May09_Interview.html

http://omstreifer.wordpress.com/2012/03/29/adrienne-rich-may-16-1929-march-27-2012/

http://coldfrontmag.com/features/essentials-adrienne-richs-the-dream-of-a-common-language

A wonderful interview from 1999 by Michael Klein, who was a good friend of Rich's, is available here–and is a must-read.

Kenny Fries just published this tribute, too.

And this from the Nation, which includes some new poems!

March 28, 2012

Ambitious poetry

Recent discussions with a few colleagues brought up the question of what poetry "should" do. This question is seldom considered philosophical–it generally occurs among inquiries more aesthetic or educational in nature. Any time we have a "should," though, we may be more clearly looking at an "ought." Which brings us to philosophy. Or to poetics.

A friend stated that poetry should have aims, aims that relate to society. She prefers the poem that speaks to "all" to the poem that speaks to (or of) the individual. This is a rather grand and ambitious "ought" for poetry, but it strikes me as valid.

Another colleague defends what she calls the "quiet" poem, the one that circles in on itself with some kind of reminder that interior reflection is occurring in the poem. This sort of poem also has, it seems to me, an ambitious project (I hate that term, but I'll go with it for now): getting the unknown reader to feel he or she is authentically inside that poem's quiet, particular, individual world. Have you ever tried to convince another person to understand your perspective on anything? It is never an easy project. It can be accomplished sometimes. To accomplish it through a poem is, frankly, marvelous. So this poem is as ambitious as the poem that endeavors to speak to all.

Donald Hall has a significant essay on this topic, ambition and poetry, and edited an anthology of essays on various views of what poetry's ambitions might be. I turned to it again last night when mulling over the topic of what poetry "ought" to be, or to do, or to say.

Hall begins, "I see no reason to spend your life writing poems unless your goal is to write great poems." And that is certainly ambitious. I do feel that is my goal; I don't expect to attain it. Heck, if I produce even one poem that is great, I will be happy. Hall also writes, "We develop the notion of art from our reading." Those texts are our models of what great, ambitious, lasting art (poetry) is.

So we develop the idea or aesthetics of what great art is through our enjoyment, study, acculturation, through the models we choose–or reject–ourselves.

Hall wanders into the controversy over writing workshops (the essay is from 1983). I'm not interested in that discussion for this post. But I constantly remind myself of this section from his essay:

Of most help is to remember that it is possible for people take hold of themselves and become better by thinking. It is also necessary, alas, to continue to take hold of ourselves—if we are to pursue the true ambition of poetry. Our disinterest must discover that last week's nobility was really covert rottenness, etcetera. One is never free and clear; one must work continually to sustain, to recover. . . .

I'm prepared, on my best days, anyway, to accept that I will never be free and clear, that as a poet and as an amateur philosophe (is there any other kind?) I will always be working, continually taking hold of myself, trying again and again to become better by thinking. For me, this is what poetry ought to do.

March 25, 2012

Early blooms

Quince blossoms.

The strangely warm weather around this equinox has sped spring along. Above, one of my favorite ornamental shrubs, a quince (Chaenomeles speciosa) in the named variety "Tokyo Nishiki." I love its pale blossoms that lack the orange-y hue of the more common varieties of chaenomeles.

While it's lovely to see the sun, blue skies, and so many flowers, it is worrisome because an open winter requires–in our temperate region–a rainy spring to make up for the lack of snow-melt. Instead, we are three inches below the average precipitation for March. It is unusual to have to water the spinach bed; usually, I am instead dealing with sprouts that pop up far from the intended rows because heavy rains have dislodged them.

Of course, everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it, as the old saying goes. I am just going to wait and see what happens. Will we get our blackberry frost? Will it be a hard frost that kills off the redbuds and damages the early blossoms? Will we get a freak April blizzard to bookend our freak October blizzard? Or will we have a dry, too-warm spring that means the daffodils wilt early, few blossoms in May, and a tough summer for food crops?

Of course, everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it, as the old saying goes. I am just going to wait and see what happens. Will we get our blackberry frost? Will it be a hard frost that kills off the redbuds and damages the early blossoms? Will we get a freak April blizzard to bookend our freak October blizzard? Or will we have a dry, too-warm spring that means the daffodils wilt early, few blossoms in May, and a tough summer for food crops?

I have some thoughts about gardening in drought years, but I am crossing my fingers that maybe we will get spring rains after all.

Anyone know a rain dance, chant, or prayer?

March 20, 2012

Next door to God

~

I'm currently reading a new Tupelo Press anthology of essays by poets, A God in the House. The essays are based on interviews with poets whose work engages with "the spiritual" or with "faith"–often in similar ways, though attained through widely varying means and experiences.

It's lovely to savor these thoughtful commentaries on the spiritual. Many of the poets wrestle with the concept of faith, soul, or the spiritual as they try to put into words what that feels like. Poets know better than most people the limits of what we can say in words, and they push at those limits in and through their work.

And this book features some marvelous poets. Jane Hirshfield, Jericho Brown, Grace Paley, Carolyn Forché, Li-Young Lee, the incomparable Alicia Ostriker, Gregory Orr (one of my long-time favorite living poets), Annie Finch, and many others. Even if you are not interested in poetry all that much, the anthology is valuable if you are interested in the spiritual and how we obtain, understand, incorporate, question, and express it.

Can we attain transcendence? Or immanence, instead? Or are we fooling ourselves altogether?

Good questions.

~

When I was a very young child, my father, a newly-minted Presbyterian minister, was assigned to a small parish in a rural area of New York. We lived in a ranch-style manse across the driveway from the 19th-century shingle-style church. We had a large yard which bordered a large field. There was a post fence along the side of the church yard and a barbed-wire fence in back of our own yard. I liked to sit on the post fence's wooden stretchers and pretend I was riding a horse. There were tall pine trees at the front of the church and I recall watching birds fly in and out of the trees and also in and out of the eaves of the steeple. All of those memories I now associate with church-going and whatever the spirit is. I always think of that time of my life as the days I lived next door to God.

I was raised in the culture of God-the-Father. My father, my human father, was the man behind the pulpit. He wore flowing robes and he sang beautifully, but what I liked best was watching him as he opened the enormous Bible and read from it.

Yes, I was a bibliophile from the get-go.

~

I suppose the words mattered. Certainly the verses, the language of scripture, its pacing, and the intonation of recitations, creeds, and prayer–not to mention the music–made their way into my forming mind. I learned to read by doodling on church bulletins and pretending to follow along in the hymnals as we sang "Fairest Lord Jesus" or "The Doxology." But I do not recall ever believing, quite, that the words equaled the spirit, even though I memorized that in the beginning was the Word and the Word was God.

Now I have come around to words again. (Writers do that.) I am not in the right frame of mind to write eloquently, as the writers in A God in the House have done, about how my poetry, my practice, my beliefs entwine with the spiritual. Perhaps someday I will, inspired by the thoughts and reflections of others. It is a brave thing, to write about one's faith–so personal. I am grateful to the editors (Illya Kaminsky & Katherine Towler) who envisioned this project and interviewed the poets; and I heartily recommend this book.