Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 80

May 21, 2012

Reveries toward childhood

My childhood was happy and full of isolation—bored, lonely, occasionally melancholy daydreams and reflections. Some readers will find contradiction in that opening sentence, but Gaston Bachelard would have understood. His chapter (in The Poetics of Reverie) on Childhood and Reverie resonates deeply with me.

The claims Bachelard makes for the crucial importance of childhood reverie are that the child, solitary, daydreaming, finds happiness as the “master” of his or her reveries and that poetry is the way adults can return to the deep daydreams of childhood in which humans are—briefly—free beings and fully receptive: “Poets convince us that all our childhood reveries are worth starting over again.”

He further claims that images “reveal the intimacy of the world” and that all poetic images are a kind of remembering. I suppose this particular claim for poetry puts Bachelard in the “deep image” arena of poetry—Rilke, for example, as filtered through the concepts of Carl Jung, whose influence appears everywhere in The Poetics of Reverie. I waver in my complete acceptance of this claim, though I can’t yet articulate why—because I do agree image can evoke, or even be part and parcel of, intimacy. It may not be the sole method of achieving the shock of recognition or the tug of familiarity among readers, however. I’d assert that Ammons, Menashe, even Ponsot (in her tiny poems in Springing) get there by other means.

What I love about Bachelard’s philosophy on childhood reveries is the idea of “reveries toward childhood.” Interesting phrase, and I wonder if the translator (Daniel Russell) struggled with it. To dream toward childhood denotes an intentional action, a moving forward in order to reach back, a paradox. He claims we can almost reach (regain) the child’s “astonishment of being,” our “world of the first time,” through reading poems. We daydream with the poem itself…not with the poet, who remains a distinct individual with his or her own being and past.

I’ve experienced this feeling, and now Bachelard has described it for me.

The philosopher was late in his life when he composed these reflections; this is his last book. As he explores the “uselessness” of childhood memories, the flashes of recall through sensory stimuli, he posits that reveries toward childhood nourish the person who is in “the second half of life.” Combining memory and reverie can restore us, he says; and to do so, we first beautify our pasts—even our tragic episodes are reconsidered, reconstructed, through the lens of distant memory. (Hence the opportunity for sentiment). I think he means that once we have dealt with vivid past traumas earlier in adulthood, older people are able to recall the amazement of having once been new to the world. Perhaps this is merely sentiment, but it is certainly a phenomenon that appears in many works of drama, fiction, even memoir.

Bachelard describes such experiences as “the strange synthesis of regret and consolation” and adds that “a beautiful poem makes us pardon a very ancient grief.” (I love that sentence.)

In this way—among other ways, I might add—poetry’s images help us believe in the world, revive “abolished” reveries in a fresh light; the poet’s images may not be our images at all, yet they work to move the reader toward childhood, by which I mean toward a seeing-afresh of human experience. I may be parting ways with Msr. Bachelard here, for he classifies these images as almost wholly archetypal, and I do not; nonetheless, I don’t think our differences negate his claims nor hurt my general agreement with his insights. The amazement that took off the top of Emily Dickinson’s head when she read a great poem, the astonishment of being that arrives via the poem, strikes me (and the pun is intended) as exactly like the Zen whisk: “Wake up!”

And what is a child but a being who is wholly awake to the world?

“When we are children, people show us so many things that we lose the profound sense of seeing,” Bachelard says. Yes, like Whitman when he “heard the learnéd astronomer”… Whitman’s speaker—the child in him—ventures outside to see the stars. He does not need to be shown.

This is a long blog entry, I know. But if you’ve gotten this far, I hope you are eager to go read some poems now.

Wake up and dream!

Still daydreaming in adolescence…(Switzerland, 1974)

May 18, 2012

Outside the (type) box

Many years ago, back when there was a career called typographer, I was one. I apprenticed to typographers because I had superior proofreading skills, a background in art and design, there was a recession, jobs were few, and I was a quick learner. In an essentially blue-collar job, I was decidedly outside the box: I was a 21-year-old female with a BPhil in philosophy and literature. But I was a terrible waitress. So, in desperation, I essentially talked my way into a job at a typeshop in New York.

A voracious reader all my life, I felt attracted to the potential type offered for expression via the medium of words. I’d studied art since the second grade, so the aesthetic side of typography fascinated me, too. I got into the business just as the field was waning due to the innovations offered by phototype methods, digital typography, and the invention of desktop publishing. Nevertheless, typography kept me fed and housed for a few years while I learned to discern the differences between various counters, serifs, descenders, dashes, x-heights, weights and the rest. I read books on the history of type design and the history of the alphabet itself. My obsession with words and letters kept me inside the typography box, though I suppose I was often more like a stray Caslon e in the Helvetica drawer.

Wood type was no longer in use, but I used to purchase wooden type fonts–the individual letters–and type cases, because they are so folk-art-appealing and so potentially useful. As collectors began to scour flea markets for wooden type, I bought metal fonts and slugs instead; I’m particularly fond of ampersands and dingbats. (If you’re in Wisconsin and you want to see what the age of wooden type in the USA was like, check out the Hamilton Wood Type and Printing Museum.)

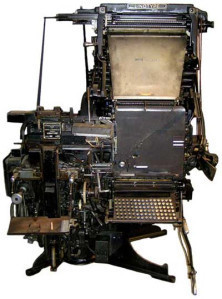

Two of the shops I worked at still used metal type occasionally, though they had mostly switched to digitally-mastered film type; and one shop boasted three Linotype machines. Two of the machines worked. The other was there for parts. The typesetters were all WWII veterans, and the smell of molten lead wafted through the building…it really felt like the end of an era. And it was.

Mergenthaler’s Linotype machine

Working at typeshops engaged my brain in novel kinds of problem-solving and detailed observation, taught me about the lives and careers of men who could have been my great-uncles, satisfied–sometimes–my yearning for aesthetics in the workaday world. An elegant logo or headline still pleases me. I learned about all kinds of odd and wide-ranging things while proofreading, too, while I marked up thousands upon thousands of proof pages; and during my breaks, I read novels. One old-timer at a shop I used to work at told me, “Every proofreader I ever knew read books on his break.” He shook his head as if that were sheer lunacy.

Today, I might note that every computer programmer I know spends his or her break time (and post-work hours) at a computer. It is nice to love something about the work one does for a living.

Typographers today are designers and computer graphics folks who understand how to digitize and digitally set and “cut” fonts for virtual pages. The design tolerances are different, though the challenges of readability and clarity and appropriateness remain. As for proofreaders, there are fewer every year, even though we certainly could use them. AutoCorrect and SpellCheck are woefully inadequate proofreading systems, as I constantly remind my students who don’t know your from you’re or their from there or then from than.

And as for me, I have moved from proofreader and typographer to tutor, instructor, poet…jobs that suit me a bit better, where my quirkiness is more tolerated and thus more conventionally acceptable. I continue to admire thinking and being that is outside of the box, however, and in that spirit I offer you some artwork that moves type outside of its outmoded, old-fashioned box. Click on the cityscapes link to find metal-type cityscapes by Hong Seon Jang. For what artists can do with letters, see also my earlier post on Steve Tobin’s sculpture, “Syntax.”

May 17, 2012

Creative reading

“There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion.” —Ralph Waldo Emerson

~

There’s a difference between simple literacy and genuine reading; that difference is partly discovery, partly imagination, partly hard work, and largely enthusiasm.

“To have great poets, there must be great audiences too,” said Walt Whitman.

Yes, I know I have covered this ground in previous posts. What interests me, though, is the way working on my writing has made me a more active and imaginative reader than I once was. Which may seem an odd thing for a lifelong bookworm to say, but as Stephen King has observed, “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write.” The implication here suggests these skills–or crafts, or tools, or processes–are conspecific. Conspecific is a science term meaning belonging to the same species, and I think it’s an apt word to describe what I am trying to say here. We can have stories without writing, but we cannot have writing without context, whether it is grocery lists or epic narratives; in the literate world, our texts provide us with practically boundless context if we use our imaginations to proceed beyond our physical, past, or immediate experiences into hitherto unknown worlds. When writing imaginatively, we have to engage with what we’ve learned through reading. The writer must be a reader.

Perhaps there are other forms of reading: listening, observation. But we are basically still within the taxa of story. My latest reading material is Brain Boyd’s immense and intriguing volume On the Origin of Stories. This book and Bachelard’s The Poetics of Reverie are producing quite an intellectual and creative mash-up in my mind and firing up some slower synapses that tend to lead to writing of one kind or another. I think there will be poems…sprung from luminous manifold allusions…because these authors have forced my mind into working while I explore the depths of their invention.

O, let us labor over our books with joy! For one never knows what will result.

May 15, 2012

22 years ago this week

Here’s another post from some time back, one I have updated to reflect current experiences: the graduation and the 22nd birthday of the subject of this brief reflection.

The morning was hot, and I had not kept up with the gardening. I needed to get the zucchini seeds, etc. in the ground before the weather got too hot and dry. We were a little behind schedule with the garden because we had a 17-month-old, and I was 9 months pregnant. I was sowing and weeding as women have done since the earliest establishment of agriculture, heavy with child, my back aching, working like a woman obsessed.

You know, that “nesting” thing you hear about with mothers-to-be? I was a week overdue and sick of waiting around; and gardens won’t wait. The weather was perfect for planting the post-frost seeds. The time was–of course–ripe. Eight hours later, I gave birth to a daughter.

A couple of years later, too busy to write much, this set of cinquain stanzas arrived in my mind (published in 2001 in June Cotner’s anthology Mothers & Daughters, A Poetry Celebration).

Now, that infant is a grown woman with a college degree. Happy Birthday, Daughter.

To My Daughter

Early

morning I had

planted seeds, cucumber,

melon, squash—I pressed them into

warm earth.

The blood

in my body

sang and I listened for

a cry to join my own—straining

to hear.

And there

you were, all pink,

unfolding in our hands,

a blossom opening with a squall:

daughter.

© 1994 Ann E. Michael

May 7, 2012

Fragments…

I just want to re-blog this brief and thought-provoking piece by Michael Klein in Ploughshares:

Klein’s musings have inspired me to go back to my drafts of the past year and look more closely at fragments, lines, and the self in the poems.

I’ve also discovered, via Deborah Barlow’s delightful art-centered blog, Slow Muse, the art and prose of Altoon Sultan. Reading and viewing creative pieces and creative critical thinking is a marvelous spur toward one’s own creative endeavors. Although I do risk spending more time online, reading and viewing, than I ought…

Enjoy!

May 6, 2012

Manet and the Sea: a novice’s view

I wrote this essay about eight years ago while taking a class on writing art criticism with the late William Zimmer. I wrote some more traditional art-crit writing, but I liked this short piece best.

The show “Manet and the Sea” traveled several major museums and was mounted at the Philadelphia art museum in, I think, spring of 2003. My daughter is now graduating from college with a degree in biology.

Manet and the Sea: a Novice’s View

My daughter, Alice, is almost 14. She has decided tastes: a preference for the colors red and purple, for Papillion blue cheese and Belgian chocolates (the darker the better), for anchovy-stuffed olives, for horses, for Gary Cooper and Johnny Depp. She listens to Fats Waller, Tom Lehrer and the Beatles. She has no interest in clothing fashions or in 14-year-old boys. All of this makes her not-your-average teen girl, but she still does not exactly jump at the chance to visit art museums. That’s my department.

Alice therefore exhibited typical teenaged foot-dragging when I bribed her into accompanying me to “Manet and the Sea” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (expensive chocolate desserts were promised). I attended the show with members of an art criticism class, people she referred to as “art geeks”—not a promising start to our evening together; but that’s what people her age are like and I have learned not to take the sarcasm too personally. She spurned the offer, at the gallery entrance, of a taped audio tour. “Those things are always stupid,” she pronounced. The tour was not exactly stupid; but I did decide, after awhile, that the audio part of the program was the least effective aspect of the exhibit. Alice’s intuition is often pretty canny.

My kid is a widely-read, marginally sophisticated teen who’s been to many art museums but never really shown a huge interest in paintings. On the way to Philadelphia, I asked her if she knew who Manet was; she remembered Monet and Renoir, and Delacroix’s horses, but not Manet. I told her about the scandals that revolved around “Olympia” and “The Luncheon,” and we discussed subjects for art and how those change depending on society’s values. She remembered my passion for medieval art, “all those church-y pictures with saints and halos.” Subjects of the times. But this exhibit would focus on sea paintings, I told her. Boats. Harbors. They’ll be pretty to look at, I said.

And they are. Alice was not particularly taken with the early Dutch naval battle canvases, or with Manet’s “Ship’s Deck,” but most of the other paintings appealed to her. She said of “Ship’s Deck” that “you can tell he knew a lot about boats, but this painting is kind of dull and depressing.” More to her personal tastes was one of Manet’s small, impressionistic canvases, which she returned to admire several times during the evening: “Sailing Ships at Sea” (1864). She liked the abstract but sure brushwork, quick-seeming indications of small boats “with their sails moving the right way” (she learned to sail last summer and is full of the hubris of the newly-informed) and the cheerfully-colored bands of sea and sky. This is a painting she wouldn’t mind looking at every day, she said, as opposed to Courbet’s “The Wave” (1869). She admired the Courbet for its power and deep brown hues, its action—“but it’s almost too much; I would get fidgety having it in my room.” Monet’s “The Green Wave” suited her most among the wavescape paintings. She liked the way the small boats were handling the swell.

Her taste for bright colors does seem to affect her choice of favorite paintings. She liked the vivid blue-and-white poles and bright overall feel of Manet’s “Venice—the Grand Canal” and pointed out to me the small, red sailboat and tiny white seabirds that add to the perfect charm of his “Fine Weather at Arachon” (1871). Color is what appeals to her in the Monet paintings, as well, and was what surprised her most in the Morisot harbor scenes. “Look how much white she used! These are so different from the other paintings,” she observed. “Why do you think she chose to paint those scenes?” I asked Alice. She answered that flags must be fun to paint. Color again.

But tedium sets in, even amid the loveliest gallery of paintings. Alice headed out of the show to view the chanfrons (equine face-armor) in the arms and armor gallery and to wander through the European collections. And after a long wait at a nearby restaurant, she was served a warm, chocolate bread pudding with chocolate sauce, whipped cream and fresh strawberries. I opted for the crème brulée. There is food for the mind, and there’s food for the body; we shared a bit of both. On the ride home, Alice said, drowsily, “All those paintings made me want to take a vacation by the sea.” Yes, Alice—life should definitely imitate art.

[image error]

A William Carlos Williams moment in Emmaus

As the spring semester closes, I am trying to get to some housekeeping of several sorts–literal and metaphorical housekeeping. Yard work, filing, dusting, going through poems and essays and books I meant to comment upon…revisions, half-finished proposals and papers, and folders on my computer that are obscurely titled and mysteriously organized.

One thing I thought I’d do when I have a few minutes at the computer is to upload some past notes from a site I no longer use. Most of them are not worth saving, but there are a few I still like. Here’s one dated Saturday, April 18, 2009:

~

Working in the yard and garden this morning. The peas are sprouting, the asparagus are poking up. Here’s the anecdote of the day for those of you who appreciate a little poetry allusion.

My husband, preparing to move some topsoil, yells to me, “Where’s the red wheelbarrow?”

And I was able to reply, because it was literally true: “Glazed with rain water, beside the white chickens!”

[A photo from later in the day--the rainwater glaze had evaporated.]

May 4, 2012

Re-reading & reverie

Writing a book is a hard job. One is always tempted to limit himself to dreaming it.

Above all, the great books remain psychologically alive. You are never finished reading them.

–Gaston Bachelard

~

In The Poetics of Reverie, Bachelard writes of reveries on words, then moves to reveries on reveries themselves, which brings him to books. Books (philosophy, fiction, and poetry books in particular) are, for Bachelard, a kind of dream made real. Books are places to dawdle and to dream as one reads, places in which the reader can interact with imagination: the reader’s imagination, not the author’s imagination. The author’s work, if it is great, tempts readers into reverie. For this reason, Bachelard says he likes to read his favorite books many times. Each reading produces new reverie.

The chapter in which he makes his case for literature as reverie is an odd one, less of a philosophical argument and more a blend of literature, psychology–particularly along Jungian themes, and sociology, with side trips into discussions of duality (more on the masculine and feminine), the physiology of sleep/dreaming, alchemy (more Jung!), Strindberg, Goethe, Nietzsche, Henri Bosco, and Balzac.

I prefer the chapters on either side of this one (on words and on childhood). But this section made me consider the books I have re-read in my lifetime, and the idea of dreaming with literature. And the lovely idea of books as “psychologically alive.” What a terrific observation!

When I was a child, I preferred reading the next book to re-reading a favorite, although there were a few books I read over, more than once in some cases. As I read my way through high school and college, my inclination toward novelty continued. Why spend time reading books I had already read? The dreaming-with the book aspect Bachelard describes did happen for me, but the reflection lasted only as long as my engagement with each text. I was not a “close reader,” and as a result it was easy to get wrapped up in the dream-world when I read fiction. Still, the dream was the book’s dream, not my own. Closer reading is what leads to reverie, I think: re-reading and reflecting.

It was poetry that taught me to read more closely, to re-read, to dream with the text, to find true reverie in the process of reading. Poetry has always felt psychologically alive to me, and I agree that one is never finished reading a great poem. Or a great book.

I find I must also concur with Bachelard that “one of the functions of reverie is to liberate us from the burdens of life.” Nothing like a daydream, or a great piece of literature or art, to free us–however temporarily–from the things that weigh us down.

April 30, 2012

Interview

“Who has not sat, afraid, before his heart’s

curtain? It rose: the scenery of farewell.

Easy to recognize. The well-known garden…”

–Rainer Maria Rilke

~

Herewith, a recap of my side (much edited) of the ArtsAlive! conversation this past Sunday at Soft Machine Gallery. SØrina Higgins was also reading and being interviewed by Lehigh Valley Arts Council director Randall Forte, but I can’t adequately summarize her insightful comments. You can find her book here, however.

~

RF: What is your favorite poem in the collection Water-Rites?

AM: I hate to try to pin down a favorite poem, by my favorite writers or by myself. I once heard Billy Collins reply to that question by saying his favorite poem is always the one he is currently in the process of writing. That’s kind of cleverly evasive, but it’s also a little true. Though sometimes I hate the poem I’m currently working on…

I like the title poem, but I get a kick out of “Doxology” because it is so odd; and perhaps my favorite poem is “Tailfeathers” or “The Big Umbrella” or, for purely sentimental reasons—not because it is my best poem—“At Bull’s Head Pond.”

~

RF: What was the most difficult poem to write?

AM: The most difficult poem to complete was probably the long poem in the center of the collection, “The Valley, the Whitetail: A History.” That was difficult in terms of managing the length and the purpose of the poem; also, it required some research. Yes, occasionally poems take quite a bit of research—I have no desire to be inaccurate when I am writing about history or geology or botany (though I often am, inadvertently, despite my best efforts). Not all poetry is solely a work of the imagination.

There are other ways to be “difficult” however. A poem that was hard to complete was the elegy “I Shall Never Be Nearer,” which came quickly initially but took a long, long time to revise and to come to terms with. Not all of these poems—or any of the poems I write—are “about” me or my experiences, I mean, not as biographical as they may seem. But this poem does deal very specifically with the death of my close friend. It was the day after I learned of his passing, and, completely numbed and sleepless, I went with my family for a canoe trip on the lake. I titled this poem “Single Lines” for several years while I was revising it, because the images came to me in – well – single lines. Single images. I must have revised little tiny things in it oh, about 14 times. So I guess that means it was “hard to write.”

~

RF: So, the opposite question. Which poem was easiest to write?

AM: Some poems do come quickly and relatively easily. Not often, and sometimes those that come rapidly end up being sort of crappy poems. But “Lot’s Wife” only underwent about 2-3 drafts and mainly arrived, haiku-like, as a visual image that carried with it some cultural freight.

Another poem that arrived rather miraculously is “River by River.” That was the result of a car trip to Indiana with my kids and is kind of a list poem. It spooled out as a result of a kind of inadvertent prompt. Will Greenway and Elton Glaser were looking for poems about Ohio for an anthology. I read the call for work, went back to my notebook about the car trip, and recalled an incident with my son and a roadmap. The editors chose it as the opening poem in the main text of the book—immediately following the preface poem by James Wright. I felt completely graced and humbled.

~

RF: How did you choose the title of the collection?

AM: Early on, while I was working on my graduate thesis project, I chose the title for the book. I’d written the title poem but hadn’t really thought of it as the title poem until I recognized how many of the poems dealt with drought or with bodies of water or rain or artworks that portrayed water. And spelling the second word as “rites” as in ritual, rather than as an other interesting aspect of water—the “rights” to water that have caused so much conflict over the centuries—seemed fitting given that there are also rites associated with death. Funerary rites, religious rites. And rites in the form of chants and dances people have done to invoke rain during times of drought. So there’s a pun there, rights and rites, and I love literary puns.

I wanted to use Steve Tobin’s sculpture as the cover art, and Steve granted the rights for that photo (more rights, legal rights) and Keith at Brick Road approved of the image for the book cover. So I am gratified by all of that. The sculpture is an early work of Tobin’s, when he was making art using surgical glass piping. It’s environmental, site-specific art that really looks like a splashing creek. But it isn’t—it is glass.

~

RF: Tell us about your publishing history and about how and if poetry publishing has changed over the years.

AM: I had my first poem published in a tiny literary journal back in the days of Xerox-ed micro-magazines, 1981 or 82. I’ve been publishing pretty regularly since then, regularly but not ambitiously. Lots of individual poems and essays in individual journals. I had no academic reason to get a book out, and I had no real direction either. It didn’t seem to be on my to-do list when I was in my twenties. Then, at 30, I had my children. Most of my creativity went in the parenting direction, though I continued to write. I didn’t really work toward book publication until about 1999. Then I began to think about it—after David Dunn had died. In fact, I got a chapbook and a full-length collection of his work out after his death. This is hard to do—to convince a publisher to put out a book posthumously. After all, the poet cannot promote his work. That’s hard on small publishers. But I succeeded. So I thought, I guess I can get my own books published. Maybe. And my first collection was a chapbook Spire press published right after I graduated from Goddard, 22 poems about building a house, sort of ecologically-invested nature-type poems.

Things have changed in the world of poetry publishing, but it is still hard to get your work into actual print—ebooks and POD self- or partially-self-published options, as well as the web and blogs, have changed the spirit of the poetry world only marginally, though I do think these options have made it possible for more people to read and encounter poetry. The absence of critical, discerning, well-read editors & proofreaders is a loss, in my opinion; but poetry is finding other ways to deal with that. And those editors are still out there. Underpaid and overworked and cranky, but out there nonetheless. MFA programs, perhaps. Critique groups have maybe replaced salons and absinthe cafes. I don’t know.

~

RF: Any advice for aspiring poets who want to get published?

AM: I’d advise aspiring poets to be ambitious. But there are many ways to be ambitious. I’m a bit of a plodder, but I hang in there. I’m not great at networking or schmoozing or even being sort of normally assertive—I’m quite shy with strangers and hate to ask even small favors…like asking an editor to consider publishing my work. Or asking people to host readings. I mean, that goes with the job, but it’s taken me a long time to get good at doing that. I hate that stuff lots more than I hate being rejected. I don’t take the rejections hard at all. My weaknesses lie in other areas. So I can say, if you want to get published, you might not want to do what I did…anyway, if you are eager to see print soon, you might want to be more assertive and organized. On the other hand, I have been self-promoting rather badly for thirty years; and I’m okay with that because the poems are better after thirty years even if my publicity skills are not.

I’m kind of outside the box as far as the “po-biz” goes. I do my job at the college, which is only marginally poetry-related, and then only when I am teaching a section of intro-to-poetry. (Mostly I teach remedial comp and tutor students in English; I like to remind myself that Kay Ryan has the same kind of job!). I attend conferences when I can get away and when I can afford them; I have taken seminars and workshops over the years, but not religiously or frequently. The “big thing” I did for my so-called career was to get an MFA from Goddard College in 2003. This was after I had won a PA Council on the Arts Fellowship—back when the council was giving those out. Please lobby your congress people for an increase in federal and state arts funding. That was so crucial for me, earning that grant. A great confidence-builder.

Since then, I’ve earned my MFA and have four chapbooks and this full-length collection coming out and a job in academia that I probably wouldn’t have if it hadn’t been for my graduate studies and a certain amount of dogged persistence of a sort of quiet variety that I seem to possess in abundance. I still send out individual poems for publication in print and online, though not as often as I should if I were really eager to stay on the po-biz radar. I keep up a blog and a Facebook page for “promotional purposes” but don’t expect to see me on your Twitterfeed anytime soon. Technology takes me away from my reverie zone and is, generally, bad for my poetry. What’s good for my poetry are long walks, gardening, and genial loafing, visits to museums, viewing architecture and geological formations, long face-to-face chats with friends, and reading reading reading.

The quote that opens my book, the Rilke quote, kind of sums that up for me. It’s really the well-known garden that makes me recognize where the poems are coming from. The scenery of farewell, in this case, opened up the place this collection began, in loss and later in fullness.

April 24, 2012

Reading & discussion

Sunday, April 29th, at 2 p.m., I will be reading at Soft Machine Gallery in Allentown PA, at a special program hosted by the Lehigh Valley Arts Council. The event is described below:

Poetry: Getting the Word Out!

Location: Soft Machine Gallery, 15th & Green Sts., Allentown, PA

~

Ann E. Michael, author of the upcoming (June 1, 2012 release date) poetry collection Water-Rites and

Sørina Higgins, whose poetry collection Caduceus was released late last year.

Books available for sale. Refreshments provided. Sun 2 pm. Admission $10.