Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 75

January 7, 2013

New look!

I am rolling out a new professional website! At some point, this blog will probably “move” to the new site; for the time being, though, I’m continuing to occupy two zones of the internet’s vast web. However, please consider clicking on the link below to take a look at the redesign.

One reason I am so excited about this new site is that I worked closely with the young digital-graphics designer to try to compose a site that reflects a little better my public-professional-poet persona. I wanted easy navigation, an uncluttered look, informational text, and links to my books’ publishers. I also wanted the page to convey my interest in the environment and to focus a bit more on my books’ themes and styles. The site is still a bit under construction, but it is “live.”

Did I mention that the designer is my son? He graduates January 19th with a degree in computer science/digital graphics. He is initiating his way into the professional world, following his sister, who has been on her own and working since May of last year. I graduated from college during an economic recession in the 1970s, and I can empathize with the frustration my college students and my grown children are experiencing as they start to make their adult ways into the world of work. But I know they will find their paths at some point (heavens, my own path took long enough!)

Here it is. Please take a look: www.annemichael.com

January 5, 2013

Still more on ambition

My experience with college students and their wildly varying achievements, coupled with my long-time interests in temperament and neurology, led me to rejoice in the extensive sources listed in Paul Tough’s book How Children Succeed. Angela Lee Duckworth’s studies on grit, persistence, interest, diligence, and ambition are particularly relevant to my job–she’s at University of Pennsylvania, and the site for her research is here.

Ambition implies a goal; as used in the studies Tough cites, that goal is the desire or drive to be the best. Persistence is what gets us to the goal–sometimes–or at least keeps us plodding in the general direction. Diligence is what we feel we owe to the work or to whomever assigned the work; i.e., careful attention to the job and the completion of each task. Interest means we can focus without becoming distracted by other ideas, novelties, events, or tasks. And grit is composed of all of these traits but includes a crucial element: the ability to carry on after failure or loss–the determination to surmount obstacles, evade them, or compromise; or even to fail to do so, then dust off and carry on anyway.

I administered the long version of Duckworth’s questionnaire to myself and the sense I get is that the results seem fairly accurate. I’ve asked family members and colleagues to take the survey; the results jive with our intuitive “measures” of these traits among ourselves. It came as no surprise to me that I scored below the median in ambition; but when I mentioned that outcome to a colleague, she expressed surprise. She said I am “ambitious” about my poetry, noting the time I devote to reflection, revision, trying to get the poem “right.” But is that ambition or something else?

So the spectre of ambition in poetry appears again (see my previous posts here & here). Having just breezed through David Orr’s delightful if somewhat flawed book Beautiful and Pointless–a Guide to Modern Poetry, ambition in relation to poetry screams out “Do not ignore!” And the coincidence of having the “grit” research to mull over and connect with the idea of ambition and the arts. Language being flexible within context as it is, I will stay with the Duckworth definition of ambition (and my low-ish score) and state I am not an ambitious person. Nor am I an ambitious poet, but I am ambitious about my poems. I want the poems I write to be as beautifully stated as they can be; I want them to communicate as well as possible on as many levels as I can achieve; and I want them to be relevant or revelatory to as many potential readers as possible. I want the poems to exert upon their readers the desire, even the need, to pause and reflect upon necessary things. Those are ambitious aims, and I cannot claim I ever achieve them in my work. But I try.

The poets whose work is great do achieve these things–and more–in their ambitious poems.

An ambitious poet is something else again. Walt Whitman claimed himself a “loafer,” and he may not have been ambitious as a person–but he was certainly an ambitious poet. Orr positions Robert Lowell among the ambitious poets; I’d say Edna St. Vincent Millay qualifies. These writers, who composed ambitious poems, were also ambitious poets. My personality does not support this from of ambition; hence my lower score on the ambition scale reflects my personal trait, not my attitude toward my work. Duckworth’s scale isn’t meant to measure the latter.

It’s been an intriguing exercise to explore interpretations and to revisit poetry and ambition. Now, I wonder where Emily Dickinson, or Federico Lorca or Muriel Rukeyser would score in terms of ambition. Meanwhile, I am ready to go back to my own work. Plodding away. (Yes, I score above the median in persistence…)

Walt Whitman in mid-life

January 1, 2013

Freedom above utility

Susan Polgar is mentioned in Tough’s book. Her website is here: http://susanpolgar.blogspot.com/

One of the gifts I received this year is the book How Children Succeed, by Paul Tough. It’s a quick read that dovetails many of my interests: education, psychology, character, motivation, philosophy, & childraising, among others. There are several aspects of the book I could write about here; but today my frame of mind has wrapped around one particular passage having to do–well, in the book, with chess–but metaphorically and personally, with why I bother to write poetry.

In the chapter titled “How to Think,” Tough offers the stories of several chess-for-children programs and connects these endeavors with education, as well as with traits of persistence, grit, and critical thinking skills. He cites examples of chess masters the world over, of child prodigies, and of chess teaching methods; then, he connects these strands with the notion of learning “character.” That’s one of the book’s arguments: that character is learned, made up of other habitual traits, that it is not the same as temperament. One skill that good chess players learn is how to fail, how to overcome confirmation bias in decision-making, and how to immerse themselves through the habit of study (persistence). This does not mean that chess players naturally extend these abilities to other areas of their lives, but they could do so since they do possess these abilities. Tough finds it fascinating that many chess players still manage to screw up other areas of their lives…they do not choose to extend, or apply, their chess traits to things like academics, career, or personal relationships.

So choice (“volition” as he terms it, though he defines volition as closer to willpower) interferes with our application of learned ‘good’ habits. Ah, the old ‘free will’ trap…

~

But I digress.

The part of this chapter that grabbed me is a quote from chess master Jonathan Rowson. He says: “the question of chess being an essentially futile activity has a nagging persistence for me…I occasionally think that the thousands of hours I’ve spent on chess, however much they have developed me personally, could have been better spent…[yet] chess is a creative and beautiful pursuit, which allows us to experience a wide range of uniquely human characteristics.”

Sounds familiar to me. People say the same sort of thing about writing poetry. Then Rowson says chess is “a celebration of existential freedom, in the sense that we are blessed with the opportunity to create ourselves through our actions. In choosing to play chess, we are celebrating freedom above utility.”

Oh, that says it so well. Freedom above utility–choosing to create myself through my actions, which allows me, as poet and as sentient being, to experience all of those messy and sorrowful and complex and delightful human characteristics.

~

I have spent my 10,000 hours writing and am “expert” at it, yet it has brought me not money nor favor nor fame. So why pursue the path? Because it is beautiful and freeing. Because it is my form of gift–I have a small talent that I have labored at, but I am not “gifted” as a writer…yet I can see my way to thinking of my poetry as part of the gift economy Lewis Hyde elaborates upon in his book The Gift (which I’ve mentioned in a previous post). Ambition is not the same as willpower, and I do not have single-minded willpower in the task of promoting my work or my persona as a poet–no “poetry diva” am I. But I do have persistence in this one area: the writing practice and all it entails; and I do have experience with it, and I possess deep and abiding curiosity about poetry and gratitude that it exists and that I can continue to try my hand at it.

Even if it seems futile or pointless or non-productive to some people.

~

As an aside, I note that David Orr’s recent book Beautiful & Pointless: A Guide to Modern Poetry has been both enthusiastically and scathingly reviewed, so I must get to it soon. Perhaps Orr’s work will clarify my thinking on the non-remunerative, generally unacknowledged occupation that chose me long ago.

Or perhaps it does not need clarifying. Perhaps celebration is enough.

December 24, 2012

Blame & fear

Amazing, the human brain, consciousness layered over instinct, habits of thought, the ways we feel, rationalize, justify, seek for why. In the wake of tragedies, we tend to react with fear and blaming; it is as if we could only discern who or what to blame, perhaps we could learn how to prevent it. So we “reason.”

But all too often, what we are doing is not using reason. Instead, people tend to blame whoever or whatever best suits their own, already-decided view of the world and use “reason” to justify their feelings, a psychological phenomenon on which Daniel Kahneman has much to say. Cognitive biases inherently interfere with objective analysis, which is sometimes a lovely and rich part of the human experience but which also leads to terrible misuse of analysis. We usually act based on biases rather than on logic (see this page for a long list of biases). So many ways to justify our often-mistaken and uninformed beliefs or responses.

Anthropologist and philosopher René Girard offers insights into the desire to blame–a sociocultural desire, deeply rooted in the way humans behave when in groups and, he believes, one of the foundations for the development of religious rituals, among other things. As we endeavor to “make sense of” impossible events, to “discover why” they occur, we seem naturally to turn to blaming. Apparently, designating a scapegoat consoles us somehow, allows us to believe we might have some control over what is terrible, not unlike sacrificing a calf to propitiate an angry god.

~

I lived just outside of Newtown, CT for a few years in the 1980s. I still have friends there and I know the area well. It was a safe town, and it is still a safe town; only now, it is a safe town in which a terrible and statistically-rare occurrence happened. That sounds rather dry and heartless: “a statistically-rare occurrence.” Yet from the logic standpoint–if we are being reasonable–it is simple to discover that by any measure, U.S. schools are the safest place a school-age child can be. Fewer than 2% of deaths and injuries among children ages 5-18 occur on school grounds. I got these numbers from the US Center for Disease Control. Keeping an armed policeman at every U.S. school (as recently proposed by the president of the NRA) might possibly make an incrementally small difference in that tiny number. Might. Possibly. Rationally, would it not make more sense for us to address the 98% and decrease that number? Though I am all in favor of hiring more people to safeguard our cities, the only real value of such a move would be to reduce a mistaken sense of public fear.

Because we are afraid, and fear is keeping us from rational and compassionate behavior. Fear can be useful–it probably helped us survive in the wild, and it continues to serve good purpose occasionally; but human beings ought to recognize the value of fear is limited in a civilized, community-based, theoretically-rational society. Rational, compassionate behavior on the part of our nation would be to remove the lens of public scrutiny from the people of Newtown and allow them to deal with grieving in the privacy of their families and community. We cannot come to terms with private loss, nor ever understand it truly, through network news, tweets, photographs on our internet feeds, or obsessive updates on ongoing police investigations.

Fear also keeps us from finding resources of our own. It blocks us from our inner strengths. The families and friends of the victims and the killer need that inner strength more than they will ever require public notice, no matter how well-intentioned the outpourings are.

~

Blame. Whose fault is it? Children and teachers and a confused and angry young man and his mother have died violently, and I’ve been listening to the outcry all week–even though I have tried to limit my exposure to “media sources.” Here are the scapegoats I have identified so far: the mental health system; semi-automatic weapons; violent computer games; the 2nd Amendment; the media; autism; school security; the killer’s father and mother (herself a victim); anti-psychotic drugs and the pharmaceutical industry; divorce; god; U.S. legislation concerning weapons and education and mental health; bullies in schools; the NRA; the victims themselves, for participating in a godless society; poor parenting; narcissism; the Supreme Court; President Obama; the CIA. I’m sure I have missed a few. (Andrew Solomon’s recent piece in the New York Times also touches on our default blame mode; his list coincides pretty closely with mine; see this article.)

Scapegoats serve several purposes. They allow us to say we, ourselves, no matter how guilty we feel, are not at fault. They give us an excuse for disaster, something to punish or something to attempt to change through controls we can think through and develop (“logically”). And in fact some good may eventually come of the changes and the control we exert, but such change is likely to be small and long in arriving. Mostly what scapegoating achieves turns out to be bad for us, however, because what it does well is give us something to fear.

Fear motivates us to read obsessively every so-called update on the killer’s presumed (and, ultimately, unknowable) motives, to argue over the best way to address the complex and intertwined issues that each of us perceives to be the root cause of any particular tragic event. Our fears make us consumers of media, and our information sources respond to our need to know why and our desire to blame. Our fears drive us to purchase guns to protect ourselves even though statistics continually prove that more U.S. citizens are killed accidentally or intentionally by someone they know intimately (including themselves, especially in the case of suicides–which Solomon also addresses in the essay I’ve cited) than by strangers or during acts of robbery, terrorism or massacres. “News,” as we have come to know it, is predicated on reporting things that are dramatic and therefore statistically unlikely. Suppose our information sources kept an accurate hourly update on weapons-related or motor vehicle-related deaths…would we become immune to the numbers? Would we say “That’s not news”? Would we be less avid consumers of such “news sources”? Would it comfort us to know we are more likely to be struck by lightning twice than to die in a terrorist act on U.S. soil or be killed by a deranged gunman in a mall or school?

Can we delve into our inner resources of rationality in order to fight our fears?

~

I think not. Fear is not easily swayed by facts. Instinct trumps reason psychologically and cognitively in this case. Fear is so emotional that it requires a deeply spiritual, soul-searching response perhaps–instead of a reasoned one. Perhaps that is why so many of the “great religions” include stories of human encounters with a god, godhead, or cosmic intelligence which humans “fear” (though the term is used to signify awe and recognition of human insignificance rather than the fear of, say, a lunging tiger). In these stories–the Bhagavad Gita and Book of Job among them–a human confronted with the godhead recognizes such fear/awe that he can never afterwards fear anything this world has to offer. In the face of what is beyond all human understanding, there is no reasoning, and no human “feelings” that psychology can explain.

Roosevelt said we have nothing to fear but fear itself. Words well worth recalling in times like these.

~

Finally, this:

And the angel said unto them, Fear not: For, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.

Namaste, Shalom, Peace, Al-Salam. May your find the strength within yourself to make your way compassionately through this world.

December 18, 2012

Phenomenology: a beginner’s understanding

http://www.themontrealreview.com/pics2/mereau-ponty-image.jpg

“Phenomenology is the attempt to discover the origin of the object at the very centre of our experience…[to] describe the emergence of being and…how, paradoxically, there is for us an in-itself.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

The philosopher argues that while empiricism, psychology, and neurology (brain science was still in its infancy in 1951, and I think Merleau-Ponty would have been fascinated by current medical science involving brain studies) are valuable and offer insights into philosophy, they fail to uncover the origin of being. He also argued that philosophy could become less relevant if philosophers continued to ignore phenomena. Granted, many of us could not care less about the origin of being; but this philosopher claims there is no way to truth if the questioner does not recognize the limits of his or her own perspective first, including physiological limitations that earlier philosophers ignored. Because of radical, rapid developments in science and medicine during the 20th century, and the impact on medical and environmental ethics, Merleau-Ponty’s writing is significant today.

That for us in the quote above means within each individual’s perspective; that in-itself, derived from the Kantian ding an sich, means we possess the ability to ken that the other is unknowable even as we treat the other as an object empirically, physically, intellectually–hence the paradox. Those readers familiar with Kant will recognize similarities with noumenon.

One of Merleau-Ponty’s analogies involves a house. We name it: house. We perceive only one aspect of it in time: what is visible with our human eyes or our other senses. We see the front of the house while knowing the house has a back, sides, a foundation, and interior–none of which are visible to us simultaneously, given our physiology. Yet we are capable of believing (not merely assuming) that there are hidden facets to the house, the pipes, the insulation, electrical wiring for example. And we can believe in a world that embraces all of these facets, even what we cannot see, hear, touch but all of which we can “know.” The house can be a physical phenomenon, one I encounter with my physiological senses; and it can also be imagined by me (intellectually) whole or in part–the house for-me as opposed to the house in-itself–and the person next to me will experience the house for-her and even the house in-itself in a different way due to a whole spectrum of physiological, psychological, and intellectual perspectives. Are any of these perspectives “true”? Are any of them “false”? The facts of empiricism do not explain the mystery of our knowing what we cannot empirically know through induction. The hypotheses of intellectual philosophy do not acknowledge the being-here of the physical experience and the complex psycho-socio-neurological goings-on that make up cognition.

What appeals to me about phenomenology is its awareness that we are limited by our perspectives to the fields of our physical, physiological, psychological, and intellectual points of view–including the empirical, science and its “facts.” And yet, this philosophy admits of our ability to imagine beyond these limits, to speculate; we function amid apparent paradoxes such as the simultaneous existence of unity and monadic separateness, perspectives that overlap, interconnect, communicate with and relate to those other than our own perspectives (or phenomenological fields). Phenomenology accepts that the philosopher’s thinking must be conditioned by situation. Thus, if I understand it aright–and I may not–phenomenology admits of us being in the world-as-itself.

Hence:

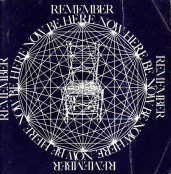

“Be here now,” as Ram Dass famously advocated in a book all of my friends had in their libraries in the 1970s.

Ram Dass’ Be Here Now

I’m over-simplifying. Yet I see a correspondence between the phenomenological approach and some aspects of (so-called) Eastern knowledge-practices/philosophies. The idea of consciousness as a network of intentions. The statement that “consciousness does not admit of degree.” The notion that actions and observations matter.

And now I am like the Zen practitioner…as far as phenomenology goes, I have “beginner’s mind.”

December 10, 2012

Learning the literary analysis

It’s end-of-semester time when I meet with students to coach them through revisions of their final papers. A fair number of those assignments are literary analysis papers, and the students I tutor tend to view these essays with dread stemming from confusion. I have learned a few methods of deconstructing and demystifying the literary analysis, but I understand these students’ frustrations. I felt them myself many years ago, as I learned literary analysis the hard way, under the tutelage of a formidable and exacting professor.

Actually, I had not thought much about learning literary analysis until a few days ago, when I had the chance to read some of my own early essays. In the bag of ephemera that contained my father’s essay on Martin Luther (see this post), there are also a few of my letters and college papers that my mother saved for some reason. How revealing it was to read my early forays into fiction analysis–and to see the comments my professor made on my work. Very astute, critical comments that confronted me, a naive 17-year-old who was accustomed to getting high grades on English papers, with all that I was assuming, leaving out, or asserting with faulty logic or lack of evidence.

It’s interesting that I rose to the challenge. I was shy and easily intimidated, and very young. The reason I did not feel utterly crushed by the professor’s comments is that this was a seminar class, discussion-based, with a great deal of face-to-face conversation among teacher and students. My professor was the most assertive, self-confident, and supremely logical woman I had ever encountered; I was intrigued by her. How on earth had she gotten that way? Was she born into it? Had her family encouraged her to be so direct, forthright, critically observant? Her vocabulary was precise. Her expectations were high; yet she insisted we teenagers had ideas that we were capable of expressing verbally and on paper.

Many students disliked her intensely, considered her too blunt, wounding, hypercritical. I respected her acuity and her breadth of knowledge. I didn’t want to emulate her, but I wanted to read what she had read and understand it as intently as she did.

I don’t think she would mind my revealing her identity, as she’s well-known for her passionate learnedness and her controversial ideas about education. You can find her on a TEDtalk on YouTube: Liz Coleman, long-time president of Bennington College. When I was a freshman at the experimental Freshman Year Program at The New School for Social Research, she was the program dean and my Art of Fiction teacher.

The title page of a much-lacking freshman attempt.

She did not coach us on thesis statements or methods of breaking the analysis into chunks of ideas supported by evidence from the text. Instead, she quarreled with our assertions, asked probing questions of our thin but possibly promising claims, and confronted us with the obvious. I was astounded by this approach to education, 180 degrees different from what I had encountered in high school. After Liz made her comments on my One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest essay, I picked up the book and immediately read it again–something I had never done before.

I had drawn parallels to the Christ narrative, a rather obvious way for a beginner to explore Kesey’s novel, but had completely failed to recognize that if you’re going to draw such parallels there comes a point where you need to recognize what the novelist does with the idea of “sacrifice”–what is gained (if anything) by it, and what purposeful and ironic twists the writer does to that narrative, and to what end(s). I was onto something when I wrote about the ‘earthly’ aspects of the characters but lost that thread in my allegorical pursuit.

My professor pointed out that I had “seriously limited the impact” of my paper’s argument–at that time, I had no idea that a literary analysis actually a form of argument–by transforming the novel into something it wasn’t, ie, a retelling of the Christ narrative. I love what she next wrote:

“That’s just not adequate to one’s experience of a novel in which earthly pleasures (the more earthly the better, it seems) are so unequivocally celebrated…[Kesey's] vision of triumph has very much to do with being alive–his communion is with the juices of life.”

The communion with the juices of life! She wrote that to a 17-year-old. I’m not sure I got the full impact then, but I sure learned a great deal from her feedback both on the page and in class. And I did begin to write better, more argumentative, more logical papers. It wasn’t the simplest way to learn how to do a close read; but then, a close read of classic literature should reveal complex insights. I had to fight my way through my own assumptions and bad logic. I had to learn to read again, and at first I felt that analysis would destroy my joy of reading; but that’s only true if you are unlucky enough to have a professor who insists that the students’ interpretations align with the teacher’s opinions.

Dr. Coleman has strong opinions about literature–and education, and political engagement, and many many other subjects. Yet I never felt she was pushing her interpretations onto us students; it seemed to me she was pushing me to do better work, to think more clearly, to read with more enthusiasm, with an alert mind. My engagement with literature, art, and much more owes a lot to her…I had always loved to read but had been in many ways a lazy reader.

I’m pretty much cured of that now!

December 4, 2012

Hinges, Hopkins, “Buckle! AND…”

Thinking about poetry again, at long last. A colleague directed me to a lovely little online post in which poet Catherine Barnett describes her attempts to create a physical analogy of poetry as hinge: here on the University of Arizona site.

Barnett writes:

As a poet, what interests me about a hinge is its two defining qualities: a hinge—like other devices—connects objects; it serves as a point of connection, a joining, a joint. But so is glue, a screw, a nail, a hasp, a clasp, a knot, a lock. What distinguishes a hinge from most other forms of connecting is the fact that it allows relative movement between two (or more) solid objects that share an axis.

In a poem, a hinge word or moment or gesture allows you to have both continuity and gap; unity and difference; such “hinges” keep the parts of the poem in some working relationship to one another and at the same time allow the poem to retain some of what Aristotle calls the unities of time and place.

How radically or loosely you want the hinge to open is a matter of temperament.

I love that idea of temperament juxtaposed with relative movement, continuity and gap. I’ve long mulled over the concept of joinery as a metaphor for some of the things that happen in poetry (even if “poetry makes nothing happen,” I do wish people would remember Auden’s next phrase that “it survives/In the valley of its making”). The hinge offers another analogy that Barnett hints at though doesn’t fully develop in her brief piece. I felt inspired to explore a poem that I think demonstrates the concept of the hinge.

The Windhover

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird,—the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: shéer plód makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

Aside from the fabulous alliterative sound-joy and astonishing rhythms of this poem, it offers powerful, realistic description of a bird that manages to operate symbolically if the reader chooses to interpret it that way (as Hopkins surely meant his readers to do). I propose that there are several hinges in this poem, most spectacularly the center line in the center stanza, exclamation and capitalization marking the spot. It is at this point in the poet’s observation that pride, plume, brute beauty suddenly buckle: the falcon wings fold, plunge, AND…the bird breaks into the dangerous shine that makes the viewer’s heart leap at the sight.

Perhaps there is a moment when the bird’s shape resembles a cross in the sky. Perhaps the sun behind the gleaming feathers sends out shimmers like flames, the glory of God illuminated. Or it’s just a falcon, handsome and gliding on the big wind, but that hinge in the poem’s line serves to alert us to the gap (the hinge-like action of wings an unintended simile) and the continuity of the poet’s observation.

There are other hinges that work in the piece, such as the hyphen in its odd place at the end of the first line, promising “king” but leading instead to the string of D sounds that drum through the second line; the closed hinge of “Stirred for a bird” opening wide into the surprising exclamation that hangs of the axis of a long dash “–the achieve of; the mastery of the thing!”

I’m not sure I’m going to attempt Barnett’s original idea of making a poem physically into a hinge (though I have some tantalizing thoughts about ways one could accomplish that); I hope eventually to write about the joinery analogy. Meanwhile, however, I’m spending the evening with Hopkins’ “Windhover” in my mind. A pleasant way to open, or to close, a mild day late in autumn.

~

November 28, 2012

Reading in Allentown

Tonight, I will be reading at one of my favorite places: A public library. With one of my favorite fellow-writers, April Lindner.

Information on my Events page. More later…

November 24, 2012

Still more difficult books

I am perpetually out to confound myself.

After reading Larson’s odd but lucid koan-like “biography” of John Cage’s creative interpenetrations with Buddhism, I have begun Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s 1961 text The Phenomenology of Perception. Already I have encountered some thoughts in Merleau-Ponty that relate to the indeterminate, a concept that excited Cage and that Larson demonstrates shares a great deal with Zen. But reading Merleau-Ponty is more challenging than reading Larson’s book, as I have less background in early 20th-century philosophy than I do in Zen studies. I enjoyed reading Bachelard’s imaginative, image-based take on phenomenology because I could relate to it on a poetry level even when I missed some of the philosophical antecedents (or contemporaries) he references. That possibility isn’t available to me with Merleau-Ponty.

I do appreciate that his writings were formulated before technologies that made neurological processes visible and while psychology was still bickering with the “hard sciences” about empirical measurements. (Actually, that bickering continues in some areas of study.) I do not think Merleau-Ponty would agree with, say, E. O. Wilson’s rather reductionist idea of consilience. Yet clearly, the philosopher was willing not to discount the sciences or empirical study–he just felt those areas were not of particular use to a philosopher, particularly a phenomenologist.

The body is what we have with which to experience the world, Merleau-Ponty tells us. But the human body is limited by its perceptual experiences. Structures–and that includes abstract structures such as thought–appear to have recognizable patterns, and the perceiver may posit cause and effect as a result. But another body may perceive differently, due to a different biological process or a different time or any number of physical or environmental variables. We perceive yellow with the cones and rods of our human eyes; the dog or the bee, the spider or the hippopotamus, may have eyes that do not see yellow as we do. Is yellow a quality or a perception? Merleau-Ponty seems to be saying (I am not very far into the book, so I may be in error) that science cannot be objective, even though it is science that made us question our senses: “We believed we knew what feeling, seeing, and hearing were, and now these words raise problems.”

And how does this all relate to consciousness? Maybe I’ll figure that out as I go along.

~

Here’s a sentence I love because it speaks to me of poetry and the arts on the level of ambiguity: “[Science, with its categorization] requires that two perceived lines, like two real lines, be equal or unequal, that a perceived crystal should have a definite number of sides, without realizing that the perceived, by its nature, admits of the ambiguous, the shifting, and is shaped by its context.”

Or perhaps by observation? A little Uncertainty Principle going on there. I feel that good poems change when observed, and change in the context of the reader’s time, place, experience; that they possess ambiguity not in the sense of rhetorical wishy-washiness but in the rich sense of complex possibilities, indeterminacy, transformation.

~

I’m especially pleased to have found Bernard Flynn’s article in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (the link to the entire article is above), which ends with the following reflections on Merleau-Ponty:

If we think how the thought of Merleau-Ponty might prolong itself into the 21st century, or as it portends a future, then we cannot not be struck by the fact that his philosophy does not entertain any conception whatsoever of an ‘apocalyptic end of philosophy’ followed by the emergence of some essentially different mode of thought. Unlike Heidegger, there is no anticipation of an ‘other beginning’, also there is nothing like Derrida’s ‘Theory’ which is waiting in the wings to displace philosophy, and unlike Wittgenstein, Merleau-Ponty’s thought does not await the disappearance of philosophy. In the academic year 1958–1959, Merleau-Ponty gave a course at the Collège de France entitled “Our State of Non-Philosophy.” He began by saying that ‘for the moment’ philosophy is in a crisis, but he continued, “My thesis: this decadence is inessential; it is that of a certain type of philosopher…. Philosophy will find help in poetry, art, etc., in a closer relationship with them, it will be reborn and will re-interprete its own past of metaphysics—which is not past” (Notes de cours, 1959–60, p. 39, my translation). After writing this he turns to literature, painting, music, and psychoanalysis for philosophical inspiration.

The theme of the indeterminate frequently recurs in the thought of Merleau-Ponty. Philosophy is enrooted in the soil of our culture and its possibilities are not infinite, but neither are they exhausted. In an essay entitled “Everywhere and Nowhere, ” Merleau-Ponty explicitly reflects on the future of philosophy, he writes that philosophy “will never regain the conviction of holding the keys to nature or history in its concepts, and it will not renounce its radicalism, that search for presuppositions and foundations which has produced the great philosophies” (Signs, 157). In his Inaugural Address to the Collège de France, he claimed that “philosophy limps” and further on that “this limping of philosophy is its virtue” (In Praise of Philosophy, 61).

What will philosophy do in the 21st century? It will limp along.

Apparently, I shall be limping along with it.

November 19, 2012

Energy & stamina

I have been thinking about energy and stamina, and the difference between the two, and how they relate to creative practice. The word “energy” conjures up, for me, vigor and forcefulness, vitality, strength–a sort of bustling intensity, the kind my son exhibited when he was five years old, for example. I have never considered myself a particularly high-energy person.

Think of the cat. A cat is capable of intense bursts of energy but will also husband that energy until the moment it’s needed. The cat will also sleep most of the day, storing up energy for the necessary predatory expenditures of strength. The feline form of energy use does not suit me very well, though I am partial to naps.

Stamina, however–stamina I have possessed. Stamina is also strength, also energy, but it is of a different nature. Plodding sometimes, headlong other times, but steady in the main. The sort of focus and determination a person needs to get through the long haul strikes me as stamina. Stamina is the energy to endure.

We have the mayfly and the bee, always buzzing actively, bursting with lively energy. Or the cat, conserving and then pulsing with strength and force. And we have the snail, constant and enduring, slowly edging its way toward its object.

We have the mayfly and the bee, always buzzing actively, bursting with lively energy. Or the cat, conserving and then pulsing with strength and force. And we have the snail, constant and enduring, slowly edging its way toward its object.

My writing practice requires endurance, because I only occasionally get flashes of inspiration or insight and rarely feel surges of creative energy. Nonetheless, I have been told I am a “prolific” writer (by whose standards, I always wonder; compared to Georges Simenon and Alexandre Dumas, I am a piker). I think the reason is that I keep on. Everyone experiences setbacks, rejection, dry spells, discouragement, dull days. How we choose to deal with those situations becomes part of our practice of the discipline of art, and many approaches “work.” Whenever I read biographies of artists of any kind, or interviews with poets and writers and choreographers and composers, I recognize that (despite post-modernist critique) the life, in terms of personality and approach, does to some degree influence the art.

But the results are impossible to stereotype. A talkative, energetic artist may produce quiescent, meditative art. A dour personality can produce hopeful poetry, a still and soft-spoken person may create fierce, kinetic work.

A highly energetic person like Rimbaud can “burn out” on a major art form rapidly (though his busily-spinning, adventurous life kept going). And then there are the energetic sorts who just keep making work with boundless, apparently inexhaustible fire (see Simenon). One method or personality is not better nor more suited to art than another.

~

This is my minuscule revelation for the day: The one time I visited a shaman, I was told that my totem animal is the snail. The idea gave me a moment’s pause, but then seemed somehow very apt.

Except I was a little queasy about the slime trail.

~

I decided I can reframe the fact of slime once I recognize its purpose. It is not merely a lubricant, helping the gastropod to glide along, but also a glue that enables the creature to climb difficult surfaces, walls, and even ceilings. The layer of mucous also acts to protect the snail from dehydrating.

There must be a metaphor there somewhere. Poetry as…snail slime?

~

Time to keep plugging away, I think.