Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 67

February 3, 2014

Curiosities & stories

Here’s James Delbourgo’s recent article in Chronicle of Higher Education (I read the Chronicle regularly, if that’s not already obvious) about collections of oddities. While the article itself is sometimes a bit maddening (what is his main idea here?), it put me in mind of Mantel’s The Giant, O’Brien and of collections my friends have accrued. Toshio Odate, for example, has some fascinating accumulations he keeps in clear acrylic boxes, and some of his art constructions feature curious things: a favorite of mine is a large frame displaying every pair of sneakers his son wore as a child.

Edmund de Waal wrote movingly about objects and collections in his book The Hare with Amber Eyes. Several months ago I promised myself I’d get back to the topic of objects and their stories, but it has taken me awhile to resume my meditations on the subject. As a child, I loved wandering slowly through the world, stopping and dawdling and picking up acorns, buttons, marbles, leaves, whatnot. Sometimes I would arrange these found objects into tiny houses, or float them on puddles, or arrange them on my windowsill. I might imagine stories around them, drawing on Andersen’s “Thumbelina” or the song “Froggie Went A-Courting.”

[image error]

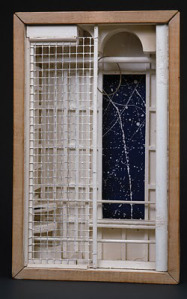

“Swiss Shoot the Chutes” by Joseph Cornell

Not too many years later, when I encountered Joseph Cornell’s work, I was enchanted. His boxes contained mysteries, stories, possibilities, and fears; and they were achingly beautiful to me. Not unsurprisingly, Cornell’s work gets a mention in Delbourgo’s piece, which is partly a review of Brian Dillon’s book Curiosity: Art and the Pleasures of Knowing.

From the Chronicle essay:

Curiosity, Dillon proposes, is a way of knowing that looks askance. It draws attention to the unexplained or overlooked fragment, to invite us, if possible, to look sideways and look closely at the same time. As such, its promise of knowledge is ambiguous. Does curiosity seek to unmask the strangeness that absorbs its attention, or is it an invitation to luxuriate in that strangeness? Does it carry an inherent Baconian injunction to go further and illuminate, or does it recommend the alternative pleasures of not knowing?

I like those inquiries and feel they may inspire some poetry. Later, while considering the way some collectors, particularly wealthy or scientifically-minded ones, made detailed lists of the oddities, Delbourgo notes that

Dillon suggests that such lists also constituted “a kind of story,” but do they? The list is an open form, not a closed and completed one. Curiosity collections could absorb countless new objects precisely because they didn’t propose a coherent narrative about them. Unlike spoils that tell of conquest, curiosities don’t preach and don’t teach. What makes them curious is their oblique relation to the world in which they’re embedded. And yet, as a matter of historical fact, early-modern Europeans accumulated curiosities in no small part through trade, colonization, and war…

The 18th-2oth century ascendancy of science and the current trend of interdisciplinary art-tech-science aesthetics gets a mention in the article, too:

Curiosity and wonder—distinct terms but often used interchangeably—turned out to be interwoven with theology, civility, craftsmanship, nature’s playfulness…Curiosity thus helped dethrone the modern fact from its hegemony over the history of science.

Again a connection with de Waal, and also with the work my brother has been doing in reconsidering the skull collection of Samuel Morton (and other early modern anthropological collectors). In the case of many people who collect ‘curiosities,’ there are thorny questions of ethics vs. the ‘value’ of extending knowledge or awareness. The political, the legal, the ethical–these can conflict with curiosity in many forms it can take, from the problematic Rauschenberg sculptural combine “Canyon” which features a stuffed bald eagle, to the superficial thrill that gets us to sit through an adventure movie even if we can guess the ending.

Curiosity is basically an exploratory response, as psychologists term it, which covers a vast arena of animal and human perceptions of the environment to orient us to potential situations and to prepare us for behavior/action. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, D.E. Berlyne studied what I call curiosity quite extensively, including some exploration into art and aesthetics though mainly concentrating on the reactive responses that make us susceptible to enjoyment or evaluation of art, humor, literature. (He published, in 1954, A Theory of Human Curiosity, which I think I must read after I read Dillon’s book).

But now I am drifting far from my topic of stories and objects. Probably that’s Delbourgo’s influence, as his essay wanders a bit, though the author cites some books I plan to add to my to-read list; for that, I am grateful, but I would prefer to look at how objects inspire stories, or make the need for stories. There’s the sun in the sky each day, and it leaves each night. We make up a story about that, or about why the leopard has spots or why there are stars in the sky.

Here’s something from my own collection of curiosities, a wooden ampersand from an antique type magazine.  And there’s a story I could tell about it which would be more or less ‘true,’ but there are better stories yet to be invented.

And there’s a story I could tell about it which would be more or less ‘true,’ but there are better stories yet to be invented.

Or, tell the story of Cornell’s “Observatory Box.”

“Observatory Box,” Joseph Cornell

January 28, 2014

Turn! Turn! Turn!

I’m thinking of Pete Seeger, who died yesterday at 94 after a full and active life of song and advocacy for peace.

This is one of Seeger’s songs, as sung by the Byrds (1965); it was my favorite song when I was 9 years old. I recognized it was from Ecclesiastes, and I loved the simple tune.

A time to be born, a time to die. Elegy & celebration.

January 27, 2014

Consciousness reconsidered

A few months back, I was reading about consciousness (see here and here). This article on “brain tubules” caught my attention, although I admit to considerable skepticism as to how applicable, or even correct, this research will turn out to be. The material seems exciting–quantum vibrations in the brain!–because of the possibilities inherent in a synthesis of chemistry, biology, and physics and how such synthesis could lead to a theory of human consciousness.

The earliest article I could find on this theory dates to 1998 (an abstract is here). I suppose I should now break down and tackle Werner Loewenstein’s Physics in Mind: A Quantum View of the Brain. But I have a huge to-read list at present and no time or concentration to get to those books. Besides, at the moment I find myself more concerned with the less empirical side of consciousness theory. I mean: belief, attitude, faith. Those non-provable abstracts that nevertheless seem so much a part of most human beings’ operating systems…the things that psychology and neurology do not seem able to answer and that keep philosophers continually at work (the only true knowledge being the knowledge that one knows nothing).

~

And maybe, as Daniel Dennett suggests, the very idea of consciousness is an illusion–the brain evolving to fool us through perception.

~

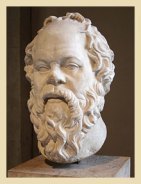

This bust resides in the Louvre,

and was found here:

http://www.humanjourney.us

/greece3.html

Do our brains fool us through our perceptions of emotion, too?

~

And how does this affect how we understand, say, literature, or art? Poetry, for example: Is it possible to deconstruct the pleasure I take from a poem into quantum vibrations in connective synapses as a result of the evolutionary process and, if so, where does the knowledge get me?

Would I still love the poem? (I think I would.) Would I consciously love the poem, consciously find pleasure and surprise in it, once I understand fully the process and development of consciousness? (Why not?) Would such knowledge flatten my emotional or aesthetic attraction to the poem? (I doubt it.)

If loving my perception of art, my relationship with it or attachment to it, is “merely” an evolutionary development, that does not cheapen or devalue the way I feel.

~

What brain studies and consciousness studies have to say about faith may perhaps set up more antagonism between science and consciousness-as-non-biological/i.e. religion, spirituality, etc. By faith I mean not necessarily religious faith but any non-provable conjecture, some of which are imaginative and potentially marvelous, not to mention potentially true. Some statements can be disproven but not proven…and there is the apagogical argument…and then there is the definition of faith (or belief) as Wikipedia defines it: “Faith is subjective confidence or trust in a person, thing, deity, or in the doctrines or teachings of a religion, or view (e.g. having strong political faith) without empirical evidence, or as confidence based upon a degree of evidential warrant (as in a Biblical sense).”

That empirical evidence thing is the perpetual stumbling-block, yet–paradoxically–it’s also what makes faith so appealingly…human. Yes, maybe we are fooling ourselves. And maybe that’s what is so marvelously cognitively neurologically fruitful and imaginative about the whole human endeavor.

January 23, 2014

Humanities high horse

It is the Year of the Horse, and I’m on my high horse again about the value of the humanities and the liberal arts education.

It is the Year of the Horse, and I’m on my high horse again about the value of the humanities and the liberal arts education.

A recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education reports on studies concerning what preparation a liberal arts degree offers to students once they enter the workforce and suggests that the long-term outcomes (in terms of career and steady employment) bode very well. As I embark on another semester of trying to persuade sophomores that the study of poetry can offer some value to their lives, it helps me to know there is at least some evidence that I’m not just making this up!

~

Artwork source: Steve Lohman of LineArt Gallery; lineartgallery@gmail.com

January 16, 2014

Lyric time

I’m currently savoring–as slowly as possible, as it is a short book–Mark Doty’s “World into Word” essays in The Art of Description. The text has been gently pushing my thoughts back toward matters of poetry.

I always think of Doty’s style, in prose and poetry, as precise and almost studied, though the studied-ness doesn’t feel overbearing but reflective; a naturalness remains that keeps the poems “hospitable” (as he puts it).

In his essay on Bishop, “The Tremendous Fish,” Doty examines the various forms of observation and focus or perspective that contribute to any work of art, although here he is of course honing in on the lyric state of mind. These passages seem to me to hearken to Bachelard (see here and here) on the temporal:

What is memory but a story about how we have lived? …there is another sort of temporality, too, which is timelessness. In this lyric time we cease to be aware of forward movement…it represents instead a slipping out of story and into something still more fluid, less linear: the interior landscape of reveries. This sense of time originates in childhood, before the conception of causality…

Self-forgetful concentration is precisely what happens in the artistic process–an absorption in the moment, a pouring of the self into the now. We are, as Dickinson days, ‘without the date, like Consciousness or Immortality.’ That is what artistic work and child’s play have in common; both, at their fullest, are experiences of being lost in the present, entirely occupied.

This is, in addition to relating to Bachelard’s concepts on reverie, a form of mindfulness that would not be out of place in Zen and would be recognizable to any artist familiar with the creative “zone.”

I’m reminded of a popular colloquialism of the 1970s: “zoning out.” Generally, the phrase signified not paying attention, being slightly stoned, out of touch: negative connotations. Yet there were people who used the term in a more positive way to mean “in the zone”–an acceptable, if “flaky,” zinging of the mind into a calm or creative space.

A space where poets might wander in “self-forgetful concentration.”

~

Let’s go…

January 9, 2014

Clear skies

Download: bowla.wav

(A friend traveling through Thailand took this photo.)

Given that these are the coldest, darkest days of the year, I have felt the need for clarity quite keenly. Today, we had clear skies. When I walked outside this afternoon, I felt as though a note from a singing bowl was vibrating through my body.

{Wake up!}

Download: bowla.wav

January 4, 2014

Poet’s truth

Hilary Mantel writes her protagonist’s view of 16th-C. poet Thomas Wyatt in Bring Up the Bodies:

~

…you trap him and say, Wyatt, did you really do what you describe in this verse? He smiles and tells you, it is the story of some imaginary gentleman, no one we know; or he will say, it is not my story I write, it is yours, though you do not know it. He will say, this woman I describe here, the brunette, she is really a woman with fair hair, in disguise. He will declare, you must believe everything and nothing of what you read… You tax him, what about this line, is this true? He says, it is poet’s truth.

…

When Wyatt writes, his lines fledge feathers, and unfolding this plumage they dive below their meaning and skim above it. They tell us the rules of power and the rules of war are the same, the art is to deceive; and you will deceive, and be deceived in your turn, whether you are an ambassador or a suitor. Now, if a man’s subject is deception, you are deceived if you think you grasp his meaning. You close your hand as it flies away. A statute is written to entrap meaning, a poem to escape it. A quill, sharpened, can stir and rustle like the pinions of angels.

~

There’s inspiration for you. Now to locate my sharpened quill.

December 28, 2013

Ignore more?

One of my brothers-in-law has been visiting from Berlin during the holidays. His young adult children all live in the U.K., and it is enjoyable to hear what they are doing and how they navigate the world as they grow–having children of their own, pursuing academic degrees or careers in the arts–and finding parallels between their lives and their American cousins’ lives. My brother-in-law (Lee, a jazz musician, listen here on YouTube) told me he recently asked his older son what the most valuable skill for the next couple of decades was likely to be. The answer surprised him:

“The skill of learning what to ignore,” his son said.

When Lee pressed a bit further for clarification, his son explained that “information overload” and real-time social and other media, along with television and Google Glass and smart phones and whatever next gets developed, overwhelm the human brain to such an extent that people tend to lose the ability to sort or to prioritize. When we get distracted, we become less efficient; several recent studies suggest that there are costs to trying to do everything at once.

So, according to my nephew (who is studying neurology at Oxford), those of us who learn to shut out unnecessary information are likely to be more successful in a highly-communicative, highly-technological social landscape. The difficulty is knowing what kind of information is unimportant. Another difficulty is that our brains are wired to sense everything. In fact, our brains are already highly developed to screen out “useless” information. Managing an even more intentional focus will not necessarily be as automatic. It may be something we have to learn: i.e., a skill.

I think I need to re-develop my ability to ignore things. It seems likely that a lack of intentional focus and time away from technology would get me working on my poetry more than I have been. One way to regain this skill might be to recharge my mindfulness/meditation practice. The intentionality of the practice, and its conscious use of both awareness and screening or letting go, seems valuable enough over all that it would be well worth the time away from multitasking.

One possible “New Year’s Resolution,” then?

Ignore more.

December 16, 2013

Studio. Space.

Contemporary artist and blogger Deborah Barlow writes: “A studio, like a womb, is a vesseled space, a geolocation from which one’s work, intentionally free of its context, can emerge.” http://www.slowmuse.com/2013/11/25/up-stairs-in-sight/

In another recent post, she talks about artists’ decisions about whether or not to offer studio tours, and art critics’ decisions about whether or not to visit studios. The critics she mentions (Saltz and Smith) prefer not to see the studios of artists whose work they are reviewing. The sense I get is that the critic needs more objectivity–a disinterestedness–and that a working artist’s studio is a personal space, one through which perhaps the critic might learn too much (context? biography? vulnerability? …one wonders).

I wrote my graduate thesis on how time works in poems, and for a long time I considered writing a followup on space in the poem, particularly the kind of vesseled, nested, interior space to which Barlow alludes (and Bachelard, in The Poetics of Space).

What spaces are conducive to the creative process? Such variety! I have friends who love to write in diner booths or cafes, and others who need complete silence, no distraction (Annie Dillard wrote in a closet; Robert Frost in a shed). One writer I know must be in bed to write. Another must be outdoors. The place matters to many people–but not to all of them.

Writing’s different from painting, sculpting–arts that require at least a few tools at hand.

But some of my writing friends need a computer, or a candle; a pencil and a legal pad, or a fountain pen and a spiral notebook; a bookshelf; darkness; classical music, or the blues.

I don’t really have a studio these days. Maybe it is time I lent my mind to carving out a creative space? –Somewhere nestled, vesseled, interior: (A Room of Her Own).

Below: A location…space, intentionally free of context.

December 11, 2013

Depression & the creative process

I was recently chatting with a psychiatrist about the creative process, specifically among poets. He admitted that he doesn’t know much about poetry, but I was nevertheless surprised to learn that he believed the stereotype of the poet who works most creatively when depressed.

“You deal with depressed people all the time,” I said. “Do they strike you as particularly motivated to do anything creative?”

He admitted that one hallmark of depression is loss of motivation–to do anything, let alone create expressive art of any kind. So it would follow, I suggested, that a period in which a person is seriously working at what he or she loves would be unlikely to coincide with a full-blown depressive episode.

“What about those poets who write about, say, staring out a window and sadness,” he asked, “They seem to write about being depressed, to express the feelings of depression.”

True, some poets experience depression (some commit suicide, too); and some express those feelings in verse. Yet none of the working writers I know who struggle with forms of depression write while in the midst of the “black mood.” They can only write well when the mood has not seized them fully; and while they may try to convey those feelings of the ‘inexpressible,’ they write and especially, revise, the work during more productive hours when melancholia has tapered a bit.

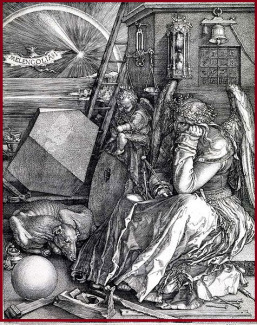

Drurer’s Melencolia I (wiki images)

It takes concentration, creativity, and analysis to craft a poem that adequately means what depression feels like. You cannot access such things when you are truly depressed. Some writers want to portray the experience; others want to explain it; still others prefer to write about the desire to escape, or even to embrace, the melancholy; others simply relate what they observe. Trying to pigeonhole all writers who address despair defies reason and suggests that all writers undergo the same feelings and experiences. Excuse me, we are individuals–diversely, wildly, enthusiastically unique.

That said, I cannot make the claim that no one has ever created a great work of art or poem while in the midst of a clinical depression; I merely posit that it’s likely that poetry composed while the author is gripped by existential melancholy will not meet the poet’s own standards.

Lewis Wolpert, a biologist and author, says, “I claim that if you can truly describe what it is like, then you have not had a true depression. It’s an illusion, and completely unlike anything else. When you are immersed in it, you enter a world without reference points, so once you recover it is very hard to relate how you felt.”

A world without reference points–that is the attraction depression might hold for a writer: the creative summons to relate an experience that is essentially beyond description. But most writers are not able to answer that summons while in the depths themselves.

And many writers are not troubled by depression at all. [See this 2012 article from the UK's Mental Health Foundation for essential insight and clarification of an earlier study--that abstract is here.] The studies do suggest that writers are more likely than the general population to have bipolar disorder, which makes a kind of sense to me: after the sinkhole of a depressive period, the active “manic” phase might permit a writer to accomplish a great deal, including possibly a description of the void. Or it might not.

At any rate, I hope that people–psychiatrists, for example!–eventually recognize that we should not stereotype artists and poets any more than we should stereotype people who have mental illnesses, different accents, or skin color that is dissimilar to our own. What makes artists “different from other people” remains a mystery despite years of research and speculation, and my gut feeling is that the difference has more to do with other aspects of the creative process than it does with depression of any stripe.