Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 64

June 29, 2014

Maximally bent & broken

bent and broken

The linguist/scholar David Crystal writes that “Poetic language is the domain where linguistic rules are maximally bent and broken.”

The context here (in his book The Stories of English) is an explanation of how historians of language accomplish their sleuthing; Crystal notes carefully the differences between written and spoken versions of the same language, not to mention dialects and artistic expression and diversified diction based upon the intended audience, and uncertainty as to region, origin, and date of the manuscripts and texts under scrutiny. He cautions readers not to take linguistic theories and received stories about language evolution too readily; the story is a multitude of stories, examinable from a variety of disciplines and perspectives. Much of the story is ephemeral, being oral/aural and carried on in dialects. A fascinating puzzle, really, full of lacunae and contradictions…and a reminder that when I am in my teaching role, I should remain mindful that Standard English is something of a misnomer. A living language, as Crystal demonstrates, operates on many levels and evolves concurrently with social, economic, religious, and technological trends.

I fervently agree that poetry offers language new routes of expression, a place to expand, warp, and break rules while managing all the same to convey information. The information may be conveyed in surprising ways, though, non-standard ways: neologisms, compound words, old words used in new fashion, or different part of speech. Poetry is a major arena for this sort of experimentation, though not the only one. Further, I am inclined to follow a non-prescriptivist approach to writing even though my job at the college is to impart the basic rules of Standard English, a task which (alas) tends to involve judging things as less-than-correct or “in need of improvement” for the sake of clarity and general comprehensibility.

Should I therefore be more tolerant of non-standard use of the apostrophe? I am not quite ready for that, because the resulting texts are still so frequently confusing. The point of good writing is, most often, to convey information–though that could be argued–

~

Crystal points out that much stereotyping of speech patterns and much arbitrary standardizing (to the degree possible) has been due to our creative writers, and compounded by writers’ love-hate relationships with printers (and, later, editors) who rely upon codification. A widely-literate audience benefits from generalized written standards, he notes–but there’s no need to become “Grammar Nazis” despite human beings’ natural inclination to be conservative and, let’s face it, contentious. He takes a sociological all-embracing stance about English, welcoming changes.

Having read this text, I am of the opinion that ours is another if those linguistically-transformative periods of messy additions and alterations thanks, largely, to technologies and the sciences but also to media and particularly social media. [viz, meme. What an adaptable coinage!] As long as I have been teaching, I have reiterated to my students that I am giving them a code, a tool, Standard Written English; the way they speak or write is not wrong or incorrect. It is simply not clear and standardized enough for academic work. Get the right tool for the job!

~

Crystal lauds Samuel Johnson for his zeal for language and languages and dialects, even as Johnson sought to “stabilize the disorder” of English in the 18th C. The author goes on to insert his view that prescriptive, “correct” approaches to the language “prevented the next ten generations from appreciating the richness of their language’s expressive capabilities, and inculcated an inferiority complex about everyday usage which crushed the linguistic confidence of millions” (not to mention enforced class distinctions even further). I need to remember this balance between clarity and variety. I admit I have been a not infrequent eye-roller at the “sloppy, slangy, abbreviated” English of television, tabloids, Twitter, texting, and my students’ lingo. It is refreshing to think of these annoyances as potentially enriching–rather than degrading–to the language I love to read, speak, and write.

When I read poems, I know there are writers who employ archaic words, dialect words, slang words, colloquial syntax, interrupted syntax, irregular capitalization and punctuation, neologisms, invented compound word-phrases, curses, technology terms, scientific jargon, Latin, Spanish, Spanglish, Chinese, obscure place names, alternate spellings (orthography)…and on and on. Some are looking back; others look ahead. Some are encapsulating the moment–now–in the framework of a verse. They bend and break the language in startling, haunting, beautiful, memorable ways. This they can do because a living language allows them to.

June 24, 2014

Mere philosophical speculation

I have been reading more of Daniel Dennett. One of his earlier books, Brainstorms, consists of essays and talks and thus, being available to read in short bursts, has served as my intellectual entertainment in between the busy social events of this particular June.

I liked three of his essays better than the others. The first one in the book describes, explains, and argues for “intentional systems;” the author also does a fairly good job of asserting that philosophers and psychologists ought to study computer models of intelligence as a means of leaning more about human intelligence. He does not make lots of mechanistic claims, however–he does not suggest human beings are mere soft machines, and he gives a good argument in Chapter 11 as to why we cannot make a computer that feels pain. But he does separate, by degrees, the differences between basic consciousness states and consciousness that exhibits intentionality, and he separates basic consciousness from simple instinct–something that confuses many people when they are posed difficult questions about non-human animal “minds”.

His essay “How to Change Your Mind” offers terrific, logical insights about human “feelings,” “intuitions,” and opinions. Dennett shifts the perspective on the psychological question of why it is so difficult for human beings to “change their minds” and to give genuinely rational (or mechanistic) reasons for doing so.

The book’s final chapter, “Where Am I?” is available as a PDF at this link, and here Dennett offers a much more entertaining and readable philosophical thought experiment on personhood (and consciousness/mind) than Derek Parfit posits in his book Reasons and Persons. Those readers who are interested in how a thought experiment can argue for the existence of a person-as-consciousness-state without embodiment-in-carbon-based-materiality, without the usually-required religious or spiritual crutch, but also without the dense counterarguments of Parfit’s approach, may wish to check out this chapter.

Granted, I understand that many people feel thought experiments are a monumental waste of time, tantamount to navel-gazing; others feel sure that teleportation out of fleshly bodies is the stuff of science fiction (emphasis on the fiction). But as our inventions permit us to test out theories that once were “mere philosophical speculation,” all kinds of surprises may await us. Quantum physics was an imagined idea, for example, that scientists have been able to revise and explore in a more machine-based way…Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions does, often, operate historically as he envisioned the process. The recent excitement over teleportation of coded data provides an example of mechanical testing of theories (here is a good basic article on the experiment for the layperson, with graphics and a Star Trek image, and here is the scientist-written article).

All of which is fascinating, yet none of which decreases my enjoyment of a run of perfect June summer days. Incarnate, I attempt meditation. There is honeysuckle on the breeze. Insects whir and buzz around me; sun warms my left shoulder. Time for consciousness. Time to be here, among the things of this world.

June 17, 2014

Parenthood & writing

My life, in my role as parent, has lately trumped my reading-&-writing time. This happens periodically and is one of the challenges–one might suggest hindrances–of being a writer who has children.

My children are grown, yet the occasional interferences continue. I rush to note that these interruptions can be marvelous; June has been pleasantly subsumed in the marriage festivities of my youngest. My blog plays a decided second fiddle to family. Or third fiddle. Or maybe just a fiddle that sits in the closet for months.

The recent New York Times Sunday Book Review offers two delightful essays on how parenthood affects writers: the columns by James Parker and Mohsin Hamid speak for me on how parenthood has informed these authors’ “writing life.” There is a difference, though it may be only one of small degree, between real life and the writing life. These men demonstrate the interaction, inspiration, and interference well, so I will let their words stand in for mine today. Please do click the link and read the essays.

Meanwhile, I observe with joy and a mixture of feelings (and a certain amount of preparation and planning and organizing) as one of my best beloveds chooses a lifetime partner and the two of them head off together into a shared life. I will be on the periphery. Which is as it should be, I suppose.

Many blessings, daughter.

June 11, 2014

Consciousness as multiple drafts

Daniel C. Dennett’s 1991 book, Consciousness Explained, has kept me entertained and interested for a couple of days now. How could I refuse a book with that title? And Dennett–whose conversational writing style appears to toss off one idea after another in quick succession–actually stays mostly true to classic philosophical reasoning in his arguments as he endeavors to make claims for what consciousness is. He begins with phenomenology as one way to initiate the concatenation of empirical science (physics, biology, neurological research) with logic. He dispenses with Husserl and the early Phenomenologists but invents his own form–hyperphenomenology–breaking phenomena into three divisions and exploring each until he arrives at a way to destroy the long-held concept of the mind, hence consciousness, as “Cartesian Theatre,” and replace that model with a construction more biologically sound.

The book is far too complex to summarize, but the concept he develops that most appeals to me is what he calls the multiple drafts theory of consciousness. Dennett draws upon neurological and psychological research as well as past and current philosophical thinking to propose that what we term consciousness may consist of multiple narratives created through physical input, memory processing, and other processes that result in fraction-of-a-second “revisions” in thinking. Narratives! Revisions! As a writer, I can certainly relate to this idea. The theory of multiple drafts consciousness would explain many phenomena, such as the unreliability of eyewitnesses, the repression and re-constructing of traumatic experiences, the embellishment of stories (as Dennett puts it, “What I should have said at the party becomes what I said at the party”)…and it has examples in the way we “tell” fiction, movies, and family stories.

Currently, I am engaged in the work of revising dozens and dozens of poems. Many drafts. Many narratives, many layers. Subtle shifts in perspective or story or language or style–which version is the real me? All of them, across a continuum.

Derek Parfit’s Reasons & Persons suggests some of the same conclusions through a more traditional philosophical approach (harder to read than Dennett’s often-humorous prose which is geared more toward the non-philosopher and which employs considerable neurological and psychological research as part of its rational evidence).

Although these texts intrigue, and are convincing, they remain speculative. For me, the science aspects of the inquiry remove none of the mystery or delight I experience in terms of my own consciousness. Nor do they negate my sense of myself as individual, unique as to perspective, or whole in myself and in the cosmos. I know that many people resist the idea that consciousness is not soul, who feel that scientific research somehow diminishes human beings into–what? Fancy hardware for intelligent software? Automatons with the illusion of free will? Purposeless life forms? Robotic zombies with no moral bearings?

A continuum version of tao

Apparently, we desire awe; but knowledge doesn’t have to kill awe.

I find myself fascinated with the ideas posed by Douglas Hofstadter wherein he theorizes consciousness-as-continuum (see this post). People love to default to a black & white way of analysis, thinking, and judging, but everything in nature contradicts that concept. No doubt our brains, wired to make quick decisions using the simplest shortcuts, sieve out a great deal of content and then justify later (Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking Fast and Slow covers this process in fascinating depth). It’s simply easier to think of balance as tao, perfectly harmonious black and white, or to sort people or objects or ideas into yes-or-no categories. But the distinctions are seldom so clear–there’s a continuum that stretches from the black to the white, as in the spectrum, as in the fringes of a forest or a meadow, as in the so-called races of human beings, as in places where societies and cultures meet and often intermingle, as in the coastline of the sea or a riparian environment. And all of those things are awesome, even miraculous.

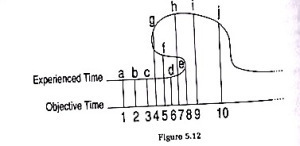

In Dennett’s Chapter Five, “Multiple Drafts vs. the Cartesian Theater,” he offers this diagram:

~

It’s a proposed version of what happens when we think.

It’s a proposed version of what happens when we think.

You will have to read the book to decipher this illustration; but I recognize in it the way I tell a story, think about a story, remember an event, record an experience, and the narrative method of the many kinds of stories (many genres, many media) that I love.

One thing it is not is straightforward. We have all those revisions to make, to layer our experiences with, to explore along the fringes of, and to find deeply miraculously awesome. Wading among my drafts now, I feel revitalized. These reflections and revisions are part of my Self as a conscious being in a physical and wonderful world.

May 31, 2014

Reading as drug

“…Let us admit that reading with us is just a drug we cannot do without–who of this band does not know the restlessness that attacks him when he has been severed from reading too long, the apprehension and irritability, and the sigh of relief which the sight of a printed page extracts from him?–and so let us be no more vainglorious than the poor slaves of the hypodermic needle or the pint-pot.” ~ W. Somerset Maugham, “The Book-Bag”

In June and July, my situation lets up enough that I am not in my office 40 hours a week and can, for a time, attend to the garden or the hiking trail or avail myself of more time to read. Yesterday, I browsed through the campus library and came away with seven or eight books. How I loved that feeling when I was a child: walking through the stacks, thumbing through card catalogues, picking and choosing, now with deliberation, now with impulse, until I had reached the borrowing limit!

It is, in a way, a kind of addiction, though for the past three decades I have been a bit more studied and less compulsive in my reading habits. A bit. Plants and animals, and the workings and seasons of the garden, are my alternate texts when the printed page is unavailable or my eyes feel tired. Certainly I read on-screen quite often, but that process is not nearly as fulfilling. I have downloaded a book by Deleuze (Difference and Repetition) as a kind of experiment; I’m not at all sure that philosophy will be comfortable to read on screen, but I suspect I might prefer reading philosophy on a computer than reading a novel on a computer.

For me, the worst thing about onscreen reading, as I possess neither laptop nor tablet computer, is the inability to stretch on a lounge chair or curl up on a sofa (or, best of all, in a hammock) while reading. And the pleasant experience of leaf-shadows gently caressing the off-white pages of a paper book, the tone of the paper shifting ever slightly as the light changes, the sensation of dozing off with a book over one’s face when the sun gets hot…book addicts find these aspects as enjoyable as the intellectual response to the material, the words themselves.

Several significant events & celebrations appear on this summer’s horizon, but with any luck I can employ my library cards to good purpose a few more times before the fall semester arrives.

May 26, 2014

Reverberations

Elegant words–and urgent ones. Lee Upton’s book of essays Swallowing the Sea offers the following passages, which are resonating with me today:

“How can we live in the midst of a reality that outpaces our ability to comprehend it? How can the ancient springs of poetry–rhythmic language shaped to be remembered, language that often assumes nature as an inspiration–survive in circumstances that disintegrate memory and nature…?

“Poetry demands that we…actively attend to both the shapes of mayhem and the shapes of controlled order as they are enacted in language. That is, in poetry more than in any other verbal genre, readers bring an expectation that not only do all elements matter down to the comma and the white space at the end of a line and between or within stanzas, but that each of these elements, no matter how widely arrayed, may tug at other elements and condition the whole. The poem is an echo chamber where we listen to the reverberations that otherwise dissolve into the white noise of anxiety.”

~

James Fenton has said, “The writing of a poem is like a child throwing stones into a mineshaft. You compose first, then you listen for the reverberation.”

~

May 21, 2014

Mimesis

Mimesis: “Imitation, in particular. 1.1 Representation or imitation of the real world in art and literature”…”a figure of speech, whereby the words or actions of another are imitated” … “the deliberate imitation of the behavior of one group of people by another as a factor in social change” (OED).

“Nature creates similarities. One need only think of mimicry. The highest capacity for producing similarities, however, is man’s. His gift of seeing resemblances is nothing other than a rudiment of the powerful compulsion in former times to become and behave like something else. Perhaps there is none of his higher functions in which his mimetic faculty does not play a decisive role.” –Walter Benjamin (“On the Mimetic Faculty,” 1933)

~

From time to time, I mull over mimesis and its role in human learning. Research on animal behavior since Benjamin was writing has somewhat undermined his assertion that the “highest capacity for producing similarities” belongs to human beings, but the concept remains generally accurate. What I notice among my students, however, is the human ability to perceive differences. My students much prefer to focus on what makes things different than on what makes them similar, but perhaps the reason is that similarities seem so obvious (due to our capacity for “producing similarities”) that we take them for granted. I introduce poetry to my students as an ancient art derived from exactly what, no one is certain, but likely from invocation or ritual or song or the human desire for narrative–and I tell them that it has been carried along through history by, among other compelling things, mimesis–that mimetic faculty we possess that makes us want to repeat or copy, in order to learn, to love, to pass along, to entertain, to communicate, to enjoy. We can look in the mirror and see another human’s face, or our own faces slightly changed through the process of copying another.

The mimetic urge has a long history among those people who intellectualize. Theories of Media (Univ. of Chicago: W. J. T. Mitchell) glossary offers a concise but comprehensive “mimesis” entry authored by Michele Puetz–the article in which I found the Benjamin quote above. (By the way, the Theories of Media glossary project is a great resource!) As I looked through my go-to philosophy resources, though, I was left with the distinct impression that the concept of mimesis has moved from the realm of the philosophical–Plato and Aristotle are our main thinkers on mimesis in the philosophical arena, so that’s pretty far back–and into the realms of sciences, both social and biological. Mimetic response has been researched, and speculated upon, by psychologists, cultural anthropologists, and neurologists (see the initial excitement about “mirror neurons” in this 2006 New York Times article). The term has found considerable employment in the writings of Rene Girard, whose writings span cultural anthropology, literary criticism, psychology, theology, and philosophy.

Writes Gabriel Andrade, in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“Girard believes that the great modern novelists (such as Stendhal, Flaubert, Proust and Dostoevsky) have understood human psychology better than the modern field of Psychology does. And, as a complement of his literary criticism, he has developed a psychology in which the concept of ‘mimetic desire’ is central. Inasmuch as human beings constantly seek to imitate others, and most desires are in fact borrowed from other people, Girard believes that it is crucial to study how personality relates to others.”

Clearly, human psychology and biology cannot be simplified to mere reflection and copying, but it is equally clear that the metaphor of mirroring can be fruitful as we explore the complexities of mind and consciousness, culture and art. Sometimes I take on the role of educator; and when I do so, I recognize the need for student learners to imitate, to hear information repeated, and to attempt to create their own “similarities.” Sometimes I take on the role of poet; and when I do that, I am clothed in centuries of form, rhythms, sounds, similes, stylings and borrowings and references: copies and reflections, altered through time.

Mirrored Room by Lucas Samaras Photo: © Albright-Knox Art Gallery/CORBIS

~

A brief aside: When I was eight or nine years old, I went with my parents to an art museum–it may have been the Chicago Art Institute–and there was an installation of Lucas Samaras’ piece “Mirrored Room.” [See the photo at left.] I was deeply impressed by the mirrored room, partly because it was inside this artwork that I finally understood, metaphorically, the concept of infinity. I was awed by the many diminishing selves I could see, the way a single “I” could change (in size), and by the tricks of light and how easily one could get lost in such a small space.

The mirrors copied me.

Mimesis implies something active, a borrowing, a taking–a kind of theft, on the one hand, and a kind of tribute or ritual motion on the other. It is also inherently continuous. The behavior does not stop at the first copy; it is carried on, perhaps through generations, like DNA.

Here is the brilliant Anne Carson:

“[It’s] what the ancients mean by imitation. When they talk about poetry, they talk about mimesis as the action that the poem has, in reality, on the reader. Some people think that means the poet takes a snapshot of an event and on the page you have a perfect record. But I don’t think that’s right; I think a poem, when it works, is an action of the mind captured on a page, and the reader, when he engages it, has to enter into that action. And so his mind repeats that action and travels again through the action, but it is a movement of yourself through a thought, through an activity of thinking, so by the time you get to the end you’re different than you were at the beginning and you feel that difference.”

~

Carson describes how I feel when I’ve read a poem or novel that moves me deeply. For that matter, it is how I feel when I find a work of visual art, or a play or dance, that seems to speak with immediacy to my own sense of experience, which arouses my passion, compassion, or emotion and alters my entire psyche for awhile– “by the time you get to the end you’re different than you were at the beginning and you feel that difference.”

Sometimes I even manage to compose a poem that gives me that sense of feeling different than I was at the beginning. On those rare times, I may look at myself in the mirror and see a changed face.

May 14, 2014

Spring fever

…I had one this year. By which I mean I had a fever caused by a viral infection that hit me at the peak of blossom time, and as a result, I spent a warm spring week mostly indoors.

I could have been out in the garden, weeding and prepping soil and planting beans, had I been hale and well. Instead–well, this year the vegetables will get a late start, and the perennial beds may not be particularly well-groomed, and the pears are unlikely to be pruned.

Laid low for over a week, I have regained enough wherewithal to return, gradually, to work and to managing short walks around the yard. Often, I take my camera. I wonder why I feel compelled to photograph the plants. I see them year after year. I enjoy looking at far better photographs by far better photographers than I, yet I prostrate myself before the gallium (mayflowers) and try to capture some feeling of their delicacy. I have pondered whether this desire stems from some Western-Romantic cultural hand-me-down, echoes of Wordsworth et al…but then I remember how Asian poetry revels in the blossom and the budding leaf and the moon’s reflection on water, and how ancient poems compare a man’s curly hair to hyacinths or a woman’s blush to the rose.

The aesthetic appeal of springtime–and all the seasons–of landscape, and of animal grace and strength–has been around for eons.

Because my brain has felt fried, I have not expended much effort on words lately.

So I will let the images speak for me

…and for themselves.

~◊~

~~

May 12, 2014

Love. Poem.

A beloved member of my family will be marrying in June, and I was asked to find a poem apropos to the celebrants and the occasion. I have written two epithalamiums (or epithalamia) and can testify to the difficulty of composing a good poem that is also a marriage poem. Anyway, in this instance, I wanted to find a suitable long-term-love-commitment poem by someone other than myself. Talk about abundance of choice!

Knowing the celebrants’ interests and tastes narrowed things down a bit, and the poem had to be “short & sweet.” The ceremony will be out of doors on a trail in the Blue Ridge Mountains, which made me inclined to look for natural imagery in the poem–but nothing so dense as to distract from the place itself.

What a splendid task! I allowed myself the luxury of looking at poetry books randomly, paging slowly through anthologies, browsing handouts I’ve collected for and from classes over the years. Just flitting from poem to poem over the course of weeks, occasionally marking something that seemed particularly likely…no pressure…

When I came across the poem “Tree Heart/True Heart” by Kay Ryan, I was startled into admiration.

It doesn’t start off like a love poem. It offers little in the opening imagery to suggest romance, or life attachment, or promise.

It is breathtakingly brief, revolves around wordplay and connotations, sounds lovely when read aloud.

The last two lines clinch the “commitment” in the poem; and the three lines preceding that final, spare, achingly-sweet sentence made me gasp when I re-read the poem, trying to figure out how Ryan managed all this in 16 lines, not one of which contains more than five words.

Okay, now you want to read the poem, right?

Okay, now you want to read the poem, right?

It was published in The New Yorker on September 26, 2011 (p. 116), and I am certain that I will be violating some sort of copyright if I reproduce it on this blog.

I hope Ms. Ryan forgives me, though if The New Yorker or her publishers find out, I may have to take this post down. It seems likely to me that The New Yorker has bigger fish to try to catch, however, so here goes. And I am putting in a plug for Kay Ryan’s books. Go buy them, preferably not second-hand, because poets make hardly any money from book sales and no money whatsoever from second-hand sales.

Tree Heart/True Heart

by Kay Ryan

The hearts of trees

are serially displaced

pressed annually

outward to a ring.

They aren’t really

what we mean

by hearts, they so

easily acquiesce,

willing to thin and

stretch around some

upstart green. A

real heart does not

give way to spring.

A heart is true.

I say no more springs

without you.

~

My beloveds–who are an ocean apart at present and miserable about it, and who aim to make sure that each has “no more springs/without you” –agreed that this poem suited their intentions, their personalities, and the leafy stretches of the hiking trail.

Thank you, Kay Ryan. Thank you, human beings, whoever it was who invented the arts, and poetry.

May 2, 2014

End of semester crunch

The university year here in the USA is almost over; at my college, today is the last day of classes, and next week is final exam week. As a result, I have little space in my mind for speculative musings and little time for reading–other than reading student papers.

This is also the time of year when my colleagues in academia, feeling stressed and slightly burned out, share stories from the trenches and sigh over perceived inadequacies of students in general, higher education in general, academic administrations in general, and life in general. I admit to occasionally joining the chorus, but this year I am making a concerted effort to refrain from generalities in order to cultivate a bit more mindfulness and compassion.

I have been thinking a great deal lately about stereotyping and how the short-cut of pigeonholing people by general traits, which demographics tends to bolster as sociologically “true,” can hinder the ways human beings interact and value one another. Most of us shy from outright stereotyping by race; and many of us are aware that there are ingrained stereotypes concerning sexual preferences, disabilities, and nationalities about which we ought to try to be sensitive. So I would like to remind my colleagues–who do have every reason to be exasperated as the academic year closes–that much as we want to generalize people by their generation or their status as students, each one of them is a human being, individual, unique, with his or her own burdens and inconsistencies, worthy of compassion.

Not necessarily worthy of a higher grade than they’ve earned…that would not be compassion so much as rescuing or caving to some sort of pressure. But when we must place an ‘F’ on the transcript, I hope we remember to do so with compassion rather than irritation, resentment, or triumph.

The “Black Madonna” –A view from the heights of the DeSales University Campus; photo by Patrick Target

There are other stereotypes we employ regularly, partly because language was invented to get information across to others rapidly, and generalities offer the expediency of compressed information. The culturally and perhaps evolutionarily ingrained “us vs. them” attitude of included, excluded, and outliers of community also lends itself to forgetting the individual. As a person who often takes such language- and thinking-related shortcuts in conversation (and in little angry rants), I am in no position to chide my fellow human beings about their shortcomings. I do, however, want to remind myself that it would be a good idea to recognize, in my heart, that general judgments of others occur all too easily–unconsciously–unmindfully.

Now, back to the pile of student papers. {crunch, crunch, crunch}