Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 66

March 21, 2014

Enter the philosophy paper…

My “day job” at a small university is part administrative, part teaching, part assessment, and largely tutoring in writing. The last of these requires a peculiar balancing act, because my directive says I must not tutor discipline content; I have to tutor students toward “clear expression” while staying within the areas of grammar, spelling, vocabulary use, assignment interpretation, thesis writing, paper structure, and documentation. As a job description, that all sounds quite clearly delineated and objective enough, but writing well cannot happen when the writer fails to understand content material. Enter the Philosophy paper.

In any discipline, it’s difficult to separate tutoring “clear expression” in terms of grammar and vocabulary without also tutoring content. With philosophy that process is especially challenging, because to a large extent, philosophical understanding (content) relies on grammar (rhetoric). A student can contradict himself simply by neglecting to type the word “not” in a sentence, rendering his attempt at argument void. Or a student may announce she will use one approach to prove her claim and then prove the claim, quite adequately, with a different (and opposite!) approach.

This bust resides in the Louvre, and was found here: http://www.humanjourney.us/greece3.html

Cases like these cause me to ponder. How can I coach the writer without offering a content-based answer? Philosophy itself supplies the method: inquiry.

“So, you say here that because Locke believed in Natural Law, he would not apply Natural Law in the case of the social contract. Can you explain that statement? Because it seems as though you are contradicting yourself, unless you accidentally added the word ‘not’ or unless you have more to say after this sentence…maybe, why he would not do so?”

“Here, you do a pretty good job explaining why beauty is in the eye of the beholder, although you need to pay more attention to your use of the comma. But back at your claim in paragraph one, you say you will prove beauty is transcendent–and your definition of transcendent doesn’t work with your argument in paragraph three…do you mean beauty is not transcendent? Did you forget a word, or are you missing a paragraph of explanation?”

When the science students or economics students bring papers to me, it is, I admit, much easier for me to stick to grammar and mechanics. The same sorts of logical structure or argument issues crop up, however. Sometimes, I feel as though I am right on the borderline, and sometimes I think I’ve teetered a bit too far into content tutorial–especially when the students are writing about history, philosophy, literature, or philosophy. Yet would any philosopher disagree that you cannot completely disentangle grammar logic from any other kind of logic? They stem from the same root.

March 16, 2014

The wildest moment

This morning we were visited by thousands of starlings, whirring in a murmuration of wings and twittering enough to raise quite a din. I was wrapped in a warm robe and standing on the back porch because my vegetable garden patch is finally free of snow, and I just wanted to remind myself that the earth lies waiting (and spring will indeed arrive). I heard the flocks arriving, not an uncommon occurrence this time of year, but had never observed such a huge group in my yard and treeline before. And they came so close! Spinning past me at eye level, five feet away.

I felt almost as if I were among them, and for the first time could see how individual birds suddenly reverse themselves–pivoting on a pinion-tip–followed by some in the group while others swooped away on a different arc. There seemed to be flocks within the general flock, each with its own pattern of loop or zig-zag, rushing level or stopping briefly on the muddy grass, some settling, some leaping, their flight paths intersecting…others taking a second or two to hover in the air as if deciding which invisible line to pursue.

The noise floored me. I felt my whole body respond, eyes wide, heart racing: awe, or elation, not fear. I noticed the neighbors’ cat, who often spends hours on my sunny back porch, had backed himself into a corner and was sitting alert but a bit cowed by the loud, wild activity of the birds.

Here’s a short article from Wired that includes a video and some links to research on the physics and dynamics of starling flocks, including the delightful theory of “critical transitions” which smacks of metaphorical possibilities I think I must explore in a poem someday soon.

I’ve looked for videos of starling murmurations, and there are many–but most of them show the flocks from a distance and leave off the noise of the birds, substituting new age music (see below). For me, part of the experience is aural. Too bad I did not have the means to capture today’s wildest moment; that must be left to the imagination.

March 13, 2014

Thing and All: Reading W. C. Williams Spring and All Through a Thing Theory Lens

Ok, herewith a little concatenation between the imagist “thingness of things” and phenomenology can be read into this critical blog post by Tom Holmes. Not all readers will want to bear with the academic, linguistic, and scholarly analysis here; but for those who do, it’s worth a read. I like the rather ridiculous but genuinely honest idea of “Thing Theory” in poetry.

Here’s an example: “Williams is rendering things, and the rendering is accomplished through the imagination rendering things physical as they are, or rendering their opacity and not their transparency.” So it’s crucial to examine relationships (subject-object relationship, etc.). I concur with Holmes’ assertion that the reader is asked–or required–to “re-see” the thing in question; note how point of view, perception, necessarily gets involved in that process. The re-seeing is a kind of re-creation within the poem’s recreational aspects (pun intended). And the poem becomes a Thing made of words, which of course is what a poem is…among other “Things.”

Holmes’ essay may suggest some controversial ways of reading and interpreting Williams and other poets. Have at that.

Originally posted on The Line Break:

Originally posted on The Line Break:

Below I read William Carlos Williams Spring and All through a Thing Theory lens in an attempt to understand “Thing Theory.” My understanding of Thing Theory may not be complete, so if you have suggestions and/or want to clear up any of my misunderstandings, please leave a comment below.

//

Thing and All

In Bill Brown’s “Introduction” to A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature, he makes a comment about Williams Carlos Williams and Williams’s Spring and All when he writes, Williams “seems to understand the process of wresting things away from life and experience to be the essential dynamic of the artist’s endeavor” (2). Later on, however, Brown misunderstands the meaning of Williams “no ideas but in things,” a quote from Williams that appears a few years later than Spring and All in the poem “Paterson.” In that misunderstanding, Brown also misses out on…

In Bill Brown’s “Introduction” to A Sense of Things: The Object Matter of American Literature, he makes a comment about Williams Carlos Williams and Williams’s Spring and All when he writes, Williams “seems to understand the process of wresting things away from life and experience to be the essential dynamic of the artist’s endeavor” (2). Later on, however, Brown misunderstands the meaning of Williams “no ideas but in things,” a quote from Williams that appears a few years later than Spring and All in the poem “Paterson.” In that misunderstanding, Brown also misses out on…

View original 4,918 more words

March 9, 2014

Writing process? Got that. Sort of.

Last year, I was invited into a blog-go-round for writers (see this post). Many thanks to Lesley Wheeler for tapping me for this 2014 blog tour on “the writing process.” I read Wheeler’s 2010 book Heterotopia and was wowed; she’s also the author of The Receptionist and Other Tales, Heathen, Voicing American Poetry: Sound and Performance from the 1920′s to the Present and other work. With Moira Richards, Rosemary Starace, and other members of a dedicated collective, she coedited Letters to the World: Poems from the Wom-po Listserv (Red Hen, 2008). We got introduced virtually via the Wom-po listserv.

Lesley is a formidable scholar and critic who writes a wise and witty blog, which you’ll find linked to her answers in the paragraph below this one. Now the Henry S. Fox Professor of English at Washington and Lee University, Wheeler has held fellowships from the Fulbright Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Virginia Commission for the Arts, and the American Association of University Women. Wheeler received her BA from Rutgers College, summa cum laude, and her PhD in English from Princeton University. Despite all these amazing academic chops, which could appear intimidating, Lesley strikes me as approachable, generously interested in the wide world (not just ivory towers), and funny.

Click here for her answers to the prescribed questions. Below are my own.

1) What am I working on?

I have a completed manuscript that I sent out last year, The Red Queen Hypothesis; but I have had a change of heart about it. I am revising it completely. It’s a major renovation, because as I revisited the not-yet-book I found myself re-thinking the purpose of the collected poems. I had originally conceived the manuscript as an experiment in nonce forms, with a biological theme threading the poems together. As I re-read my work, I realized that my thinking, my purpose, for the poems has altered. Let’s just say some major life changes have been underway in the background of my creative efforts, and the influences made themselves felt. The book as originally imagined turns out not to be the book I want to write.

So, what I’m working on this year turns out to be what I was working on last year, only re-envisioned. I did complete (I think!) a collection of poems centering on adolescent girls of the 1970s that is a sort of a girls’-eyes-view of Bruce Springsteen songs–it’s called Barefoot Girls. I’ll be sending that out to find a publisher.

Meanwhile, I am writing new work which, alas, seems to be rather dark–if you happen to consider poems about mortality to be dark.

2) How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I would love to say that my poetry is wildly original in approach or style, but it isn’t. If you were to categorize my work as “eco-poetry,” it would be different from the genre because of a quieter rhetoric. If you were to call my poetry “nature poetry,” it would not fit quite comfortably into the genre because of its trending toward the intellectual. My poetry is usually “accessible,” but I don’t eschew the multisyllabic latinate vocabulary at all costs, and my allusions are often a bit arcane. I like form and classic poetic strategies, but I also like to break rules, and I adore free verse and prose poems. What did Stevens say? “All poetry is experimental poetry.” Yes. That.

3) Why do I write what I do?

Journals, because of Harriet the Spy when I was 10, and ever since.

Blogs, to practice the less emotional, more inquisitive side of myself and because I’m an autodidact.

Essays and criticism or reviews, because writing that type of work requires skills my brain needs to exercise in order to do other things, such as be an educator; and because I love to read and think about what I’m reading.

Libretti, because colleagues asked, and new things are compelling to attempt.

Poetry, because I can’t do without it.

4) How does your writing process work?

Interesting question at this time, as I feel the way I go about writing is changing after many years of pretty solid operational process. It may be that I am getting older or because see above: significant life changes.

One thing hasn’t changed, and that is the need for a certain kind of solitude. Distractions aren’t in and of themselves anathema to my writing process, but the distractions need to be of a non-urgent kind. I don’t mind being distracted by a broad-winged hawk overhead or a siren in the distance or an overheard conversation, but sometimes even a loved one’s “Hello, I’m back from the grocery store!” shifts my focus irrevocably.

[aside: My loved ones do not really understand this effect.]

The way I begin a poem is akin to how I’ve heard mindfulness described. I allow myself to be relatively vacant, and something drops in to fill the moment. I assure you this is nothing like a bolt of inspiration from the blue; and usually all I get is a phrase, a metaphor, an image, an aphorism. But it’s a start. From there, the process is about association, relationships, combinations, experiment, and a certain amount of loopy freedom to write a bad poem if that’s what emerges.

Then, I pause. The draft sits there for days (weeks, months, years) until I decide to start revising poems, which I tend to attack in batches. That’s one thing I do differently these days: revise in bunches the way I did back in graduate school under a time crunch. What I currently notice changing, too, is the way that I enter emptiness. In years past, my favored way was to take a walk or to work in the garden. Physical issues have to some degree limited the amount of time I can spend doing those activities, and finding an acceptable substitute has been hard. I am muddling through, waiting to see what works best.

~

Next up, April Lindner and Zara Raab. They should have their writing process blog posts up sometime in the next 7-10 days; and I am excited to learn what approaches each of them takes.

April Lindner is the author of three Young Adult novels: Catherine, a modernization of Wuthering Heights; Jane, an update of Jane Eyre; and Love, Lucy, a retelling of E. M. Forster’s A Room With a View, forthcoming in early 2015 from Poppy. She also has published two poetry collections, Skin and This Bed Our Bodies Shaped. With R. S. Gwynn, she co-edited the anthology Contemporary American Poetry for Longman’s Penguin Pocket Academic series. April lives near Philadelphia with her husband and sons.

Zara Raab’s latest book is Fracas & Asylum. Earlier books are Swimming the Eel and The Book of Gretel, narrative poems of the remote Lost Coast of Northern California in an earlier time. Her poems, essays and reviews appear in River Styx, West Branch, Arts & Letters, Crab Orchard Review, and The Dark Horse. She is a contributing editor to Poetry Flash and The Redwood Coast Review. Rumpelstiltskin, or What’s in a Name? was a finalist for the Dana Award. She lives near the San Francisco Bay.

March 8, 2014

Subtle spring

Today, inspired by an apparent and, I hope, lasting thaw, I ventured out into my yard to hunt for any signs of spring. Most years, the first week of March is when we mow the meadow, cut back the buddleia, and prepare the vegetable patch for sowing peas and spinach. The snowdrops are in bloom, as well as the early crocuses, and the trees are budding.

Not so this year. I don’t think our tractor can handle mowing this just yet:

~

If I look closely, though, the signs are here. For example, the budding catkins on the silver birch:

…and the pool of green beside the river birch:

A little purpling along the thorny blackberry canes indicates some liveliness has begun.

At the foot of the downspout–water! Instead of ice!

~~

Then, the faint fuzz at the branch-tips of the staghorn sumac, a little hard to see,

but easy to sense if you touch them.

Unsightly, but still a sign of spring: litter by the road as the piles of dirty snow melt off. This brush of some kind has been twisted into an “M” by forces like plows and ice.

But the most cheering photograph, for me, is this one–taken by poet and publisher Michael Czarnecki, whose photos are available here. The photo below is of the first tapping of maple sap from his trees in New York state.

photo Michael Czarnecki,

http://foothillspublishing.com

March 4, 2014

Steel roots: Flower Show

Steel Roots series, Steve Tobin, at the Philadelphia Flower Show 2014

Terrific place for Steve Tobin’s steel roots sculptures: this year’s annual Philadelphia Flower Show. Usually, I attend–and this year’s theme is art!--but circumstances prevent it this time. But the PHS (Philadelphia Horticultural Society) has an up-to-date website, and the Flower Show has its own Facebook page; so I can attend virtually without braving the icy roads and the crowds. I will, however, miss the marvelous olfactory thrill of walking into the main hall and getting stunned by the scent of fresh flowers.

Spring is a long time coming this year. I still can’t see anything but snow in my garden. Here’s hoping for thaw and the charming sight of snowdrops blooming…

March 2, 2014

Living metaphor

February 24, 2014

“Local” artists & genius loci

Recently, a friend and I visited our small, local art museum (Allentown Art Museum). The permanent collection there has a few real highlights, which for me include the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed library from the Francis Little House and a limited but fine collection of glass and ceramic decorative arts. Like many smaller US museums, the Allentown Art Museum hosts traveling exhibits that can be eye-opening (last year’s exhibit of Lautrec’s works on paper, currently at Washington Pavilion in Sioux Falls, SD, was one of these).

Currently, Allentown’s museum is featuring work by two artists who employ very different methods, and their styles are so different that it seems silly to compare them: Matthew Daub and Paul Harryn. Both of them live in the region, however, and both might be considered painters of place.

Harryn says he is enthralled by the concept of genius loci, and there’s a decidedly spiritual aspect to his work (as well as a philosophical and poetic aspect; view his site for inklings of these). His “Changing Seasons” series stretched along one wall of the museum gallery, initially seeming like a seamless continuum, though more careful observation proved otherwise. The seasons series anchors the viewer in a temperate region in which the hues and moods of four distinct seasons are markedly obvious by color and light. In these works, the layering and erasing methods he employs are subtle, but some of the larger works depend upon a more visible shifting and experimental approach to media manipulation. The image of “Pacificus” on his website doesn’t begin to convey the experience of his assemblage paintings, which are textural, shifting, very large, and compellingly active. These three “Transcripts” were charming, if less powerful than some of the more layered works:

Transcript series by Paul Harryn

~

The near-monochrome, panoramic watercolors of Matthew Daub’s Maiden Creek series also appealed to me because of place, specific–definite–”realistic” place, if not as obviously spirit of place. This is because I know the roads and streams he depicts very well, have traveled them often; but I have seldom considered them “beautiful” enough for plein air views or photographic compositions (without omitting, say, road signage, utilitarian concrete bridges, highway off-ramps, minivans, and the like).

Daub portrays those items in his photorealistic paintings. What I found revelatory in these works is how genuinely beautiful those familiar roads are when the view or frame changes. The thin horizontal rectangle of Daub’s place-paintings accentuates parts of the composition such as bare tree branches, shadows on the curved roads, the rough texture of municipal concrete next to embankments. Daub’s choice of subject matter reminds me a bit of the later paintings of Charles Demuth, but Daub’s paintings include more of the natural environment surrounding the silos, stairs, and industrial objects.

Aucassiu and Nicolette (1921) by Charles Demuth [public domain, Wikimedia Commons]

Next time I am driving Route 143 near Kempton, I will appreciate the scenery more for having acquired, through Daub, a new perspective on the dull, drab, too-familiar landscape. The aesthetics of road-building, New Jersey barriers, highway ramps, creekside roads, and galvanized silos blend surprisingly well with the brushy trees, gentle hills, and stone barns of Berks County.~

I’ll close with a poem by Maggie Anderson, from her now, alas, out-of-print book Cold Comfort (1986). Daub’s paintings made me think of this one, though the river is different.

Gray

Driving through the Monongahela Valley in winter

is like driving through the gray matter

of someone not too bright but conscientious,

a hard-working undergraduate who barely passes.

Everybody knows how hard he tries. I’m driving up

into gray mountains and there, it may be snowing

gray, little flecks like pigeon feathers, or what

used to sift down onto the now abandoned slag piles,

like what seems to sift across the faces

of the jobless in the gray afternoons.

At Johnstown I stop, look down the straight line

of the Incline, closed for repairs, to the gray heart

of the steel mills with For Sale signs on them. Behind me,

is the last street of disease-free Dutch elms in America,

below me, a city rebuilt three times after floods.

Gray is a lesson in the poise of affliction. Disaster

by disaster, we learn insouciance, begin to wear

colors bright as the red and yellow sashes on

elephants, whose gray hides cover, like this sky,

an enormity none of us can fathom, though we try.

(© 1986 Maggie Anderson)

February 19, 2014

Psychobiology & art

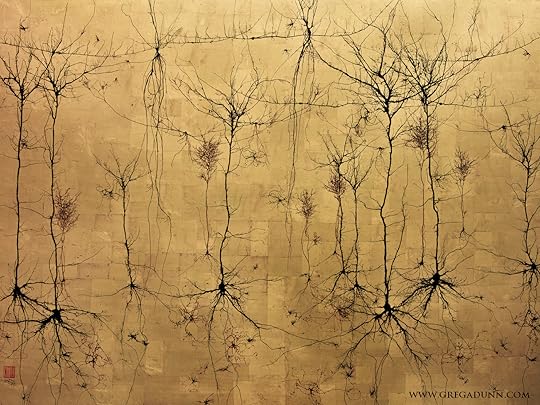

Greg Dunn’s gold-leaf neuroscience art: “Gold Cortex”

~

Howard Gardner once said aesthetics is considered the “dismal branch of philosophy” and that psychobiology, the scientific examination of art, might therefore be called the “dismal psychology.” This view derives from the difficulty of pinning down what qualifies as art, the artistic process, the artistic personality, and the like–especially the challenge of trying to categorize, measure, and in any genuine way evaluate art. Psychobiology as a discipline is new to me; is it merely an earlier form of behavioral neuroscience? How does aesthetics play a role? I went looking.

~

Here is an excerpt from D.E. Berlyne’s abstract of his exploration into stimulus behavior and art (including humor), Conflict, Arousal, and Curiosity, written in 1960:

The highly variegated human activities that are classed as art form a unique testing ground for hypotheses about stimulus selection. They consist of operations through which certain stimulus patterns are made available, and so they must unhesitatingly be placed in the category of exploratory behavior. The creative artist originates these patterns, the performing artist reproduces them, and the spectator, listener, or reader secures access to them and performs the perceptual and intellectual activities that will enable him to experience their full impact.

It’s intriguing to note the different ways a social scientist (Berlyne was a psychobiologist) uses language to write about a generally-considered subjective subject: art. Different in tone and terminology than the language a philosopher or artist would employ, the description characterizes yet another inquiry into the ontology and the exercise of art and the artistic process:

The content of art can range over virtually the whole scope of human communication. It may be used as a source of information about the appearances of objects, the course of historical events, the workings of human nature, as a means of effecting moral improvement, as a vehicle for propagating religious, political, or philosophical ideologies. Art is, however, distinguished from other forms of communication by …the communication of evaluation. While human beings may produce art and expose themselves to it for an endless variety of reasons, collative variables must play their part, as they do in all forms of exploratory behavior. They underlie, in fact, what is commonly called the “formal” or “structural” aspect of art.

The author is interested in whether psychosocial behaviors, culture-building, and communication all derive from exploratory behavior and stimulus-response and what role evaluation plays in the assessment of art, its social or moral value, artistic merit, “timeless” art, and to some extent the very making of art.

The psychology of aesthetics offers intriguing insights–if one can get past the jargon. From the little I have read about it so far, the science seems to share a few points with phenomenology: its task, according to Dr. William Blizer, is to “describe observable phenomena and to note associations and correlations among them which enable such phenomena to be predicted, controlled, and explained.” In psychobiology, the “observable phenomena” are “the behavior of the creative…artist and the appreciator.” Philosophy and psychology are strange bedfellows, though; throw aesthetics into the mix and the entire project begins to seem suspect. I am not at all sure that these inquiries end up explaining–certainly not predicting or controlling–anything about art.

I admit I prefer to read such musings when the makers themselves are doing the exploring. Nonetheless, this little intellectual excursion led to my discovery of Greg Dunn‘s amazing neuroscience designs, one of which appears above. Who knew the brain was so gorgeous?

February 14, 2014

Negotiating the storm

I have lived and driven vehicles in regions that receive a great deal of snow, but it has been awhile–and I am not as spry as I once was–and I don’t even own a pair of cross-country skis anymore (a favorite winter activity). Being responsible for keeping a house and property and cars and pets maintained while the ice comes down and the snow piles up and the heat stops working and the power goes off has also somewhat dampened my enthusiasm for snowy winters. Plowing and shoveling are no substitute for XC skiing, and harder on the back. Worries about possible frozen pipes or whether the oil truck can get down the driveway (which resembles a bobsled run) shove more leisurely, more inspired thinking out of mind.

Nonetheless, I cannot ignore the beauty of fields and trees in snow or branches rimmed with ice or–as tonight–the cold, bright moon above the cold, white earth. I remind myself that snow is the best mulch. I think of the crocus and narcissus bulbs snug and dormant below the deep drifts. The house we built does its job of upholding us and protecting us. The house, wearing its white hat…

~

A poem from 2007, an experiment in sapphics, that seems appropriate.

Negotiating the Storm

Dawn. I curl away from the ice storm toward you,

your breath cools my face and my hair, the warm room;

Love, we’ve had too few of these moments lately—

other storms plague us.

Ice assaults the windows with droves of needles,

gusts shove over pines and flatten the birches.

I am glad for the weather’s impersonal aspect:

nothing to blame there.

Sleep. The sleet does not suffer indecision.

You don’t have to touch me, just breathing is plenty.

Walls and roof are stolidly doing their jobs,

power is on yet.

Let’s recuse ourselves from the task of judging

guilt or merits the past twelve moths have garnered,

forge a drowsy peace between us and also the

guileless brute outside.

~

© 2007 Ann E. Michael