Library of Congress's Blog, page 73

June 3, 2019

D-Day’s Top Secret Map

As the 75th anniversary of D-Day approaches, Ryan Moore, a cartographic specialist in the Geography and Map Division, writes about a top-secret map used in the invasion.

[image error]

The model of Utah Beach used to brief Eisenhower and Montgomery the night before D-Day. Photo: Shawn Miller.

On June 6, 1944, Allied landing crafts approached the French coast to commence D-Day. The troops aboard knew that murderous machine gun and artillery fire awaited them.

But the liberation of Europe would take more than overcoming the German military immediately before them. It required overcoming the terrain, too: the beaches, the heights above them, the marshes just inland and the open fields cut into rectangular sections by tall hedgerows. It was the power of American mapping intelligence that helped the men in this momentous battle that became known as the “The Day of Days.”

The night before the invasion — dubbed Operation Overlord — Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, British General Bernard Montgomery and other leaders gathered in Portsmouth, a port city on the English Channel, for a last briefing on everything from the weather to the terrain. One of the key presenters was U.S. Navy Lt. Commander Charles Lee Burwell, a 27-year-old Harvard graduate who, while being “scared to death,” nonetheless delivered a short talk on the tides and the thousands of star-shaped steel barbs called “Czech hedgehogs” that the Germans had dropped just offshore to wreck landing crafts.

[image error]

Charles L. Burwell, interview with the Library in 2003.

The map Burwell and others were using for this top-level briefing was spectacular: a one-of-kind, three-dimensional model of Utah Beach, the code name for beaches near Pouppeville, La Madeleine, and Manche, France. The top-secret model, made of rubber on two 4×4 sections, depicted the beach and the interior pastures sectioned off by those hedgerows, a geographic feature that obstructed lines of sight and created conditions for deadly, close-quarter combat. Later that night, Burwell took the model aboard transport ships, showing the commanders and troops the same raised maps of the terrain they would see for the first time in a few hours.

“(The soldiers) identified with it, ‘That’s really a road I’m going to come next to a little forest, and woodland, a here’s a field,’ ” Burwell later told the Library in an interview. “I think it made a lot of difference. It was a technology worth developing.”

[image error]

Utah Beach model, detail. U.S. Navy, 1944. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Burwell hung onto the model after the war and donated it to the Library’s Geography and Map Division in 2003. You can see it by appointment.

But in mid 1944, the model, along with all other details of the invasion of Nazi-occupied France, was a closely guarded secret. It could only be unveiled once Eisenhower ordered the invasion to begin. Information on the map had come from life-threatening missions over enemy territory. Allied pilots had sortied over the Normandy beaches, under German fire, to make up-to-date, stereo aerial photographs, which provide the illusion of three dimensions to the viewer. American and British reconnaissance teams, who risked life and limb, had gathered information on sandbars and other features otherwise unobservable from photographs and maps.

This data was sent across the Atlantic to the Navy’s Special Devices Division in Camp Bradford, Virginia, which assembled the model. Just prior to the invasion, American pilots flew it back to Portsmouth, the staging ground for the invasion. There, Burwell and others used them in their briefings to Eisenhower and Montgomery.

“I would have preferred to go on one of those beaches,” Burwell said of his nerves that night, in the Library interview. He recalled the auditorium, that the models were elevated so that they could be clearly seen – and that Montgomery, the legendary British commander, was a dapper dresser. “He didn’t look like he was going to battle; he looked like he was going to Greenwich village night club.”

[image error]

Eisenhower giving final instructions to paratroopers before D-Day. U.S. Army photo. Prints and Photographs Division.

The crux of the D-Day plan was that Allied troops were to land between the Cotentin Peninsula and Le Havre and gain a secure foothold for reinforcements and supplies. The Americans were to take Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. The British and Canadians were to seize three beaches code named Gold, Sword, and Juno. In order to execute the plan, the tides at Normandy had to be low, thereby exposing the star-shaped Czech hedgehogs, so that demolition teams could knock them out. The moon would have to provide ample light for paratroopers to drop in behind enemy lines the night before. Allied meteorologists predicted that between June 4 and June 6 that those conditions were likely to be met.

But foul weather intervened, delaying the invasion. The troops, having already been briefed and aboard transport ships, had to wait it out in rough seas, as commanders feared that if they returned ashore, they might let the secret slip.

The bad weather passed. The secret held. And on June 6, the invasion began.

Paratroopers dropped in behind enemy lines an hour or so after midnight. Infantry and tanks hit the beaches at dawn. On Utah Beach, the men rapidly overwhelmed the surprised defenders, suffering roughly 170 casualties. The scene at Omaha Beach was dramatically different. Some 24 miles away, the troops there endured withering fire from a determined German defense, leaving some 2,000 men as casualties. Airborne troops suffered the worst, with 2,499 casualties. In all, more than 4,400 Allied troops were killed on D-Day.

[image error]

Overhead view of the entire map, showing English Channel, beaches, and inland fields. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Still, by mid-afternoon, tens of thousands of troops were coming ashore, along with tanks and transports and machinery. These reinforcements were needed to secure the beaches and to push inland.

“Just chaos,” Burwell said, recalling the number of broken-down jeeps in the sand on Utah Beach and the waves of troops and tanks still going forward. He had come ashore, just for a few minutes. He was standing on the real ground that the model had depicted, and the troops who had used it were now moving inland.

The liberation of Western Europe was underway. There would be many hard-fought battles before Nazi Germany surrendered 11 months later. As Eisenhower said of D-Day, it wasn’t the end, but it was the beginning of the end.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 31, 2019

Pic of the Week: Walt Whitman Birthday Edition

[image error]

Whitman autographed this photo by Alexander Gardner. Feinberg-Whitman Collection.

Walter Whitman (no middle name, thanks) was born on this day in West Hills, on Long Island in New York. Somewhere out there in the cosmos he loved, the man’s spirit is now 200. The Library has the world’s largest collection of his books, manuscripts, prints, photographs and related material. You can spend ages exploring it all, but here’s the short version:

His parents were of Dutch (mom, Louisa Van Velsor) and English (dad, Walter Sr.) ancestry. The family wealth, once respectable, was dwindling as the years passed; the family lived in a log cabin with a wooden fence around at the time of his birth. He was the second of eight children and his parents moved the family to Brooklyn when he was three. They were so poor that Walt had to leave school to work when he was 11, but his parents were nonetheless filled with a love of the nation. Proof: They named other sons George Washington Whitman, Thomas Jefferson Whitman and Andrew Jackson Whitman.

Walt went into the newspaper business, bless his heart, and was editor of the Brooklyn Eagle, a respectable outfit, at the age of 26. He liked to travel, write and observe the often brutal world around him. The beauty in it dazzled him. He wrote a book of poems called “Leaves of Grass” when he was 34. You may have heard about this.

Fame followed, though not necessarily fortune. He always had a job – journalist, editor, government clerk — never married and seems to have lived a happy life with a series of male companions (likely romances) and created, through his poetry tied to the national sensibility, the mythology of the American ideal.

“I stand for the sunny point of view,” he once said, ” stand for the joyful conclusions.”

Today, we wish him one big barbaric yawp of birthday happiness. You can send along your wishes, perhaps, by transcribing some of his writings.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 29, 2019

North Mississippi Home Place

[image error]

Michael Ford’s work in 1970s Mississippi was the foundation of his new book.

Heat. Molasses. Wooden houses, tin roofs. Grist mills. Mules, ears twitching. Metal on iron. Ice falling into a glass. Screen door hinges. Wind in the oaks. Eight-track music from the truck. Long orange sunsets that hang in the sky, a gloaming that gives way to a deep, penetrating darkness ruled by crickets and cicadas and four-legged animals that move, unseen, in the woods.

Northeast Mississippi’s hill country is a largely forgotten corner of the nation, peculiar in its mixing of Appalachian white culture and African American life more associated with the Delta on the western side of the state. It’s been one of Michael Ford’s artistic muses since the early 1970s, when he made “Homeplace,” a half-hour documentary that enshrined the place and time. A photographer and filmmaker, his subject was the vanishing culture of rural, agrarian America, where craftsmanship and self-reliance molded the shape of daily life. He was on point — one of the villages he filmed, Chulahoma, is now listed as an “extinct community,” and the general store he filmed and photographed there is long gone.

[image error]

M.R. Hall. Photo: Michael Ford.

This bittersweet perspective informs “Northeast Mississippi Homeplace,” a book of Ford’s photography and writings published this month by the Library in association with the University of Georgia Press. It encapsulates Ford’s original work and a trip back to the same places a few years ago. The Library’s American Folklife Center acquired Ford’s Mississippi collection in 2014 — several hundred photographs, film reels, manuscripts and audio recordings — and the book grew out of that project.

North Mississippi “is a special place, a special part of America,” said Todd Harvey, a collections specialist in the AFC and curator of the Alan Lomax Collection, during a recent onstage conversation with Ford and Aimee Hess, the book’s editor. The conversation, part of the Botkin Lecture Series, was at the Whitthall Pavilion, and launched the book’s publication to a full house.

Ford grew up in the northeast, but took his young family to Mississippi in the early 1970s to work on an in-depth exploration of the folkways of one of the poorest places in America. He apprentinced himself to blacksmith Marion Randolph Hall, whose shop in Oxford was just off the town square that William Faulkner had made so famous. He hung out at Hal Waldrip’s General Store in Chulahoma, watched A.G. Newson make molasses, went to Othar Turner’s barbecues (featuring fife and drum music) and studied how Riller Thomas made quilts.

“When I got to north Mississippi and went wandering in late afternoon when it was first frost, I knew what I was seeing,” Ford said during the onstage conversation. “People were self-sufficient,without a lot of outside stuff.”

[image error]

Michael Ford discusses his work with Aimee Hess, managing editor of the Library’s Publications Office. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The first lesson Hall taught him about blacksmithing? When looking at a piece of metal in the shop, “spit on it to see if it’s hot.”

Mississippi is that kind of place — gut-bucket deep with labor, practicality and mother wit. Ford, new to an old place, was struck by its poverty, by the raw relationship of people to nature. He stuck to a few counties that are to the south and east of Memphis, tucked below Tennessee and not far from the Alabama line. Interstates were things that ran someplace else. In these rolling hills and small villages, he struck up friendships and stayed for four years.

“They’re about the land,” he writes about his pictures of the era, “and about the people living their lives as best they can in the circumstances they are in. I was there in a rural America that was at its end.”

In his lecture, four decades later, he counted himself fortunate to have done so.

“I was lucky to get it,” he said, “while it was there.”

[image error]

Riller Smith ‘s quilts on the line. Lafayette County, Miss., 1972. Photo: Michael Ford

May 27, 2019

Clara Barton: A Memorial Day Story

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

Civil War nurse Clara Barton traveled to Falmouth, Virginia in December 1862, anticipating another bloody battle and a crush of wounded men needing medical assistance. Shortly before the December 13th battle of Fredericksburg, Barton gazed out over the tents and campfires of the Union troops in the Army of the Potomac. She imagined she “could almost hear the slow flap of the grim messenger’s wings, as one by one, he sought and selected his victims for the morning sacrifice.”

[image error]

Clara Barton to her cousin Elvira Stone, 2 a.m., December 12, 1862, Clara Barton Papers

“Oh! sleep and visit in dreams once more, the loved ones nestling at home,” she silently willed the soldiers. “They may yet live to dream of you, cold lifeless and bloody.”

Barton’s fears proved accurate for the Union, which in defeat suffered more than 12,000 casualties. Among the deceased was Lieutenant Edgar Marshall Newcomb of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry. Barton recorded Newcomb’s (which she also spelled “Newcome”) death on December 20 in a pocket diary she kept while tending the wounded at a Union hospital established at Lacy House in Falmouth. According to comrades, Newcomb had been shot in both legs while carrying the national flag during a charge on December 13.

[image error]

Excerpt from Barton’s diary regarding Edgar Newcomb.

Unlike many of his comrades, who died alone on the battlefield, or surrounded by strangers in a field hospital, Barton noted that Newcomb saw familiar faces in his final days. Edward Fitzgerald, a comrade in the 19th Massachusetts, tended to the 22-year-old lieutenant, and Newcomb’s brother, 17-year-old Charles, had arrived for a visit before the battle and “remained to care for him until his death.” By Civil War standards, Newcomb’s passing counted as a “Good Death” in Victorian terms, with the deceased attended by friends and family, and able to express parting words.

Newcomb was buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

[image error]

Edgar M. Newcomb, from an 1883 memorial publication.

His memory, however, lived on long after the Civil War. In 1883, Dr. A. B. Weymouth published a memorial sketch of Lieutenant Newcomb’s life and wartime letters. The book confirmed Barton’s presence at Newcomb’s deathbed, standing in for his mother as his mind wandered at the end.

Years later, Charles revisited the scene of his brother’s death at Lacy House. “It was an affecting scene to see him kneeling over his brother’s blood, which still remains on the floor,” remembered the new owner’s son, “and can never be erased.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 24, 2019

Pic of the Week: Crazy Rich Asians Edition

Novelist Kevin Kwan looks over a collection of Asian Division items with South Asian Specialist Jonathan Loar, May 22, 2019. Photo by Shawn Miller.

“Crazy Rich Asians” was the book that started it all for Kevin Kwan, the Singapore-born, New York-dwelling visual consultant and novelist. The 2013 satire about fabulously wealthy Chinese ex-pat families living (and loving and gossiping and shopping) in Singapore became an international bestseller, spawning two sequels and a hit 2018 film directed by Jon M. Chu. He stopped by the Library for an onstage conversation about the trilogy of books this week, and included a visit to the Asian Division’s collections before the show.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 22, 2019

Fragments of History

This is a guest post by John Hessler, Curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology and History of Early Americas at the Library of Congress.

As a linguist obsessed with the earliest history of writing, I am used to dealing in fragments. A shattered chunk of engraved stone, a handful of shards of painted pottery, a surviving blot of ink on vellum – sometimes these are the only evidence we have of long-lost scripts and languages. Small and insignificant as they may seem, they give us glimpses into great works of literature and poetry that we will never really know.

You find such fragments in the world’s great libraries all the time. Pulled from the bindings of books, unearthed from archaeological digs, donated by antiquarians, they can, despite their incomplete nature, become critical pieces for reassembling puzzles of the ancient world.

[image error]

Medieval manuscript fragments found in the binding of a Portolan Atlas by Placido Oliva.

Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress.

Historian and bibliographer Seymour de Ricci, born in 1881, knew this. Early in his career, he was a scholar of ancient Greek and wrote about the graffiti found in ancient Egyptian tombs – some of the world’s ultimate literary fragments. Later, he turned his attention to medieval manuscripts and tapestries. After many years of research conducted in places like the Library of Congress, he produced the landmark “Census of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the United States and Canada,” in 1935.

He also donated a small collection of rare papyrus fragments to the Library. They include pieces from two of the earliest works of literature known in the West: “The Iliad,” by Homer; and the book of Isaiah in the Bible.

The fragment of Homer that de Ricci collected is a section from Book II of “The Iliad,” which tells the tale of the Trojan War. This masterpiece of storytelling was, throughout the Greek world, told orally at first, and was later set down on papyrus, the medium of choice for ancient Egyptian, Greek and Middle Eastern scribes. The oldest complete manuscript dates from the 10th century, so any fragments from earlier versions help trace the poem’s history — and de Ricci’s fragment is from nearly 1,000 years earlier.

[image error]

Fragment of Homer’s Iliad from the Seymour de Ricci Collection. Rare Book and Special Collections, Library of Congress.

It’s from a section of the poem in which Homer begins to explain the details of the Greek war on Troy. He introduces Odysseus and Nestor, who support the main movers and shakers in the story, Achilles and Agamemnon. The fragment is the center part of the text from lines 466-477 (approximately shown in red). The complete section, translated here, narrates the drama of the warring forces gathering on the plains outside Troy:

So tribe on tribe, pouring out of the ships and shelters, marched across the Scamander plain and the earth shook, tremendous thunder from the trampling feet of men and horses drawing into position down under the Scamander meadow flats breaking into flower—men by the thousands, numberless as the leaves and seedlings that flower forth in the spring.

The armies massing, crowding thick and fast as swarms of flies seething over the shepherd’s stalls in the first spring days when the buckets flood with milk—so many long-haired Achaeans swarmed across the plain to confront the Trojans, fired to smash their lines. These men who are as goatherds among the wide flocks easily separate them in order as they take to the pasture, thus the leaders separated them this way and that toward the encounter, and among the powerful Agamemnon…

The scribe who wrote de Ricci’s fragment spelled several words differently than we see in other versions, and inserted an additional word here and there. This can be expected in a poem that was repeated orally for centuries, and then written down by different scribes in different places. Fragments like these let scholars explore these differences and see what they might mean.

The Isaiah fragment of de Ricci is from the 4th century, or about 1,200 years after the original was written, perhaps by Isaiah himself. The fragment has writing on both sides of the papyrus, from Isaiah 23:4-7 and 10-13. It is a small part of a prophecy about the cities of Tyre and Sidon. The full section reads:

Be ashamed, Sidon, fortress on the sea, for the sea has spoken, “I have not been in labor, nor given birth, nor raised young men, nor reared young women.” When the report reaches Egypt they shall be in anguish at the report about Tyre. Pass over to Tarshish, wail, you who dwell on the coast! Is this your exultant city, whose origin is from old, whose feet have taken her to dwell in distant lands?

Any ancient record of the Bible is important, and this one allows us to conclude that the fragment was once part of a codex or book. Note the round dot, the hole in the margin, which was once used to sew the sheet into a binding.

[image error]

[image error]

De Ricci fragment, Book of Isaiah, from the early 4th century. Rare Book and Special Collections. Library of Congress.

History is the story of fragments—what survives and what does not. For many manuscripts, for which there are no surviving complete copies, or whose history we know little, fragments are sometimes all we have to go by. For texts like these, and for linguists and scholars like de Ricci and myself, no piece is too small to save.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 21, 2019

Chronicling America: 15 Million and Counting!

This is a guest post by Nathan Yarasavage, a digital projects specialist in the Serial and Government Publications Division. You can find more on the Headlines and Heroes blog.

This week we celebrate an exciting milestone. Chronicling America, the online searchable database of historic U.S. newspapers, now includes more than 15 million pages!

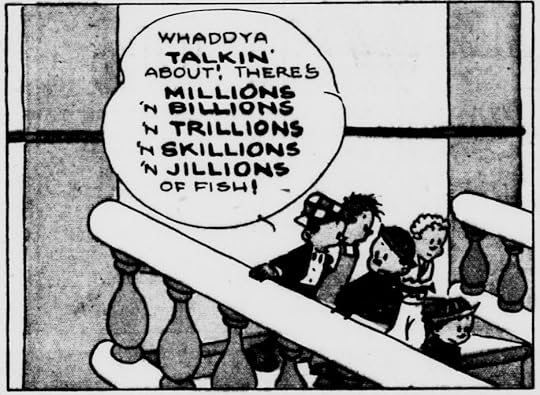

“WHADDYA TALKIN’ ABOUT! THERE’S MILLIONS ‘N BILLIONS….” Evening Star, September 18, 1932.

Since 2005, libraries, historical societies, and other institutions throughout the country have contributed newspapers from their collections to Chronicling America. This process is part of the National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP), a collaborative program sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and the Library of Congress. To date, we have more than 2800 newspapers from 46 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia. To mark the 15 million milestone, we are throwing a #ChronAmParty on Twitter to highlight all of the things to be found in 15 million newspaper pages – from the funny and fantastic to the historically significant!

“Science Finds the Father of the Cat – 15,000,000 Years Old.” The Washington Times, October 17, 1920.

“REPRESENTATIVES OF 15 MILLION POTENTIAL WOMEN VOTERS PRESENT PLANKS AT CHICAGO.” The Washington Herald, June 9, 1920.

We’re also unveiling a set of interactive data visualizations that help reveal the variety of content available in a corpus of 15 million digitized newspaper pages which you can find on this site - Chronicling America Data Visualizations. These data visualizations, which include coverage by time, coverage by state, and coverage by language and ethnic press, were created using Tableau Public. Head over to The Signal tomorrow for a blog post that goes into more detail on Chronicling America and these new tools!

To help celebrate these exciting accomplishments, please join our #15Millionpages #ChronAmParty on May 21st. All throughout the day, NDNP partners will be tweeting what is sure to be an eclectic assortment of content on the theme of #15Millionpages. Follow along and retweet our finds to your own followers or tweet your own discoveries! Just include #ChronAmParty #15Millionpages to join in the fun. Throughout the year, we’ll continue the #ChronAmParty with a changing theme every third Tuesday of the month. We’re looking forward to celebrating with you!

Questions about NDNP or Chronicling America? Contact ndnptech@loc.gov

And subscribe to our recent additions feed for more content updates!

May 20, 2019

Crowdsourcing Invitation: Help Tell a Civil War Soldier’s Story

By the People, the Library’s crowdsourcing transcription project, is rallying readers to complete 500 pages from the “Civil War Soldiers: Disabled but not disheartened” campaign before Memorial Day. These were gathered by journalist and chaplain William Oland Bourne as part of a left-handed penmanship competition for Union soldiers who had lost their right hand or arm during the conflict. Here, Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division, writes about one of the soldiers in Bourne’s penmanship contest.

“It was a day long to be remembered by those engaged in it, and by millions of liberty loving people,” Private Alfred D. Whitehouse recalled of the first battle of Bull Run near Manassas, Virginia, on July 21, 1861. That day certainly changed Whitehouse’s life – he suffered a wound that led to the amputation of his right arm and the end of his military service.

[image error]

Cover page of Alfred D. Whitehouse’s second contribution to the left-hand penmanship contest sponsored by Wm. Oland Bourne’s newspaper, The Soldier’s Friend. William Oland Bourne papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Born in 1839 in London, Whitehouse immigrated to the United States in 1849. His family settled in New York City, where Whitehouse became a sign painter. In February 1859, he enlisted in Company D, 8th Regiment New York State Militia, known as the “Washington Grays.” Upon the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861, Company D marched south, first to Annapolis and Baltimore, then to the Kalorama section of Washington, where the men mustered in as three-month recruits. Few people on either side of the war anticipated the conflict would last longer than that. Company D soon joined General Irwin McDowell’s forces, aiming to drive Confederate forces under General P. G. T. Beauregard from Manassas Junction.

[image error]

Surgeon’s certificate documenting Whitehouse’s amputation, noting that it was “3¾ inches from coracoid process.” Alfred D. Whitehouse pension file, application 290, certificate 9627, Record Group 15, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

On July 21, “a beautiful Sunday morning, calm, and serene, to [sic] sacred to be disturbed by the horrid din of battle,” Whitehouse remembered, Federal and Confederate forces clashed in the first major land battle of the Civil War. It resulted in the rout of the Union army. Around 3 p.m., a minie ball pierced Whitehouse’s right arm about two inches above the elbow. He was taken prisoner by the Confederates and transported to Richmond. Surgeons amputated his right arm so near the shoulder that he could not wear an artificial arm.

Following his parole in October 1861, Whitehouse returned to New York City where he was discharged for disability in November. After having given his right arm to save the Union, Whitehouse became a naturalized U.S. citizen in December 1861.

His war now over, Whitehouse secured a government pension for his war wound, married his wife Mercy, returned to sign painting and mastered left-handed penmanship. When Bourne’s The Soldier’s Friend newspaper sponsored left-hand penmanship contests in 1866 and 1867 for previously right-handed disabled veterans, Whitehouse entered both contests. His first essay, awarded a twenty-dollar prize for ornamental penmanship, recounted his military service and feelings about the war effort.

“I thank God who hath spared my life, to see Victory and Peace,” he closed his essay, “although at a terrible sacrifice.” His more ornate second entry included his photograph and poetry, the theme of one poem urging Americans to give disabled veterans “work that we can do.”

[image error]

William Oland Bourne papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

Government records, city directories, and other sources document that Whitehouse continued to make a living with sign painting and civil service positions (clerk, watchman) in the New York City area. He and Mercy had six children, four of whom lived to adulthood. Mercy died in January 1919, and Alfred followed his wife of nearly fifty-four years the following month. They are buried in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

May 17, 2019

Remembering I. M. Pei

I.M. Pei died Thursday at his home in Manhattan. He was 102. In recognition of his extraordinary achievements, we reprint this guest post by Mari Nakahara, curator of architecture, design and engineering in the Prints and Photographs Division, focusing on his items in the Library. It ran on his 100th birthday.

[image error]

Former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy with I. M. Pei in 1964. He is speaking to the press about funding for the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum, which he designed.

Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei celebrates his 100th birthday today, April 26. The Library of Congress is fortunate to have original design sketches by I. M. Pei as well as thousands of his manuscript papers.

With the beautiful spring weather in mind, I decided to revisit this master designer’s work by looking first at his drawings for the Louvre Museum in Paris—I did so while picturing myself humming “Aux Champs-Élysées” and enjoying the walk from the Arc de Triomphe to the Louvre. I then turned to Pei’s designs for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

[image error]

Whimsical rendering of Pei’s design for the Louvre pyramid by architect Walker Cain, 1984.

French President Francois Mitterrand commissioned Pei in 1983 to develop a solution to a long-term problem with the Louvre’s original entrance, which was no longer adequate to receive the increasing number of daily visitors to the museum. Pei’s innovative idea was to insert a 71-foot glass and metal pyramid in the center of a courtyard surrounded by centuries-old structures. As an architectural grad student when the pyramid was completed in 1989, I admired his imagination and technical skill tremendously. A shape from ancient times, made of modern materials, melded beautifully and astonishingly into a historical setting.

Pei’s careful study of axes in site-plan sketches includes one drawing in black and red that determines the center of the pyramid by connecting the site to the Arc de Triomphe. A site plan on the bottom of a sheet of yellow tracing paper highlights the large main pyramid with a small pyramid behind, water pools and pavement patterns. All of these elements repeat the diamond shape, reflecting the pattern in the metal structure of the pyramid.

[image error]

Site plan sketch for the Louvre, 1983.

[image error]

More sketches for the Louvre site plan.

Pei also created multiple models such as those shown below to study the structure and opening of the pyramid.

[image error] [image error] [image error]

Before the Louvre project, Pei worked on a design for the National Gallery of Art’s East Building in Washington, D.C., between 1968 and 1978. I can easily walk down the hill from the Library of Congress to the National Gallery of Art to enjoy this Pei masterpiece.

The triangular rhythms in the design sketches are what reveal Pei’s genius for me. He turned the unusual trapezoidal shape of the site to great advantage by creating a smaller but identically shaped trapezoid area and dividing it into two triangular buildings. The axis of symmetry of the larger triangle aligns perfectly with the central axis of the West Building. The hand-drawn diagram with diamond-shaped grids served as the basic module of Pei’s design of the East Building.

[image error]

Diagram for Pei’s design for the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, 1969.

[image error]

Sketches for the East Building.

Pei started one of his most significant commissioned projects in 1964—the John F. Kennedy Library. During the selection of the architect for the Library, Jacqueline Kennedy visited each nominated architect’s office. While others welcomed her with their definite ideas, Pei told her he did not yet know what the library would look like. He said he would like to propose his idea after he spent more time contemplating what John F. Kennedy would have liked. I think that was a gutsy response, and this answer caught her heart. As shown in the photo at the top of this post, Mrs. Kennedy and Pei are both smiling at the press conference called to announce that public contributions to the fund for the library had exceeded $10 million.

Pei’s serious studies of traffic and pedestrian flows also influenced his design for the Kennedy Library. The two sketches below, right, represent his concept of combining triangular, square and round shapes.

[image error]

Site plan study for the Kennedy Library.

[image error]

Sketches for the Kennedy Library.

“I think a great building reaches into the folklore, if that is the right word, of the people it serves,” Mrs. Kennedy wrote to Pei in 1981.

“I hope it touches you the way it has affected the lives of all who live near it or discover it as they come to Boston by land, sea or air. . . . You made that possible for Jack. I will always think of it as a monument to your spirit—to your humanity and perseverance. . . . With my deepest thanks that stretch back through the years, and with much love, Jackie.”

This letter must have been very rewarding, especially after all the challenges Pei had to overcome during this project.

Congratulations on your centennial birthday, Mr. Pei!

Learn More

The Prints and Photographs Division holds visual materials from the I. M. Pei Papers. Additional materials will be transferred from the Manuscript Division this year.

The I. M. Pei Papers are available for research in the Manuscript Division.

The Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division holds transcripts and photographs from the John Peter Collection (1951–95), including an interview with Pei.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

PIc of the Week: Roses Edition

Flower arrangement. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Sometimes, it’s just all about the image.

In that spirit, we bring you this gorgeous photograph of a floral arrangement from a special-collections display this week that was part of a memorial to former Librarian of Congress James Billington, who passed away in 2018. It’s so delicate, so lovely and so mesmerizing. Happy Friday.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers