Library of Congress's Blog, page 77

April 4, 2019

Winifred Phillips: The Music of the Game

Winifred Phillips is a maestro in the world of video game music. She’s composed soundtracks for major hits such as Assassin’s Creed Liberation and The Da Vinci Code. She’s won industry awards. She’s written a book on the subject. She’ll be speaking this Saturday at the Library’s Augmented Realities Mini-Fest on the intricacies on composing for games, as opposed to traditional film and television scores.

We caught up with her by email earlier this week for a fun Q&A.

[image error]

Photo credit: Winnie Waldron.

In “A Composer’s Guide to Game Music,” you write that the idea for composing game music came to you while playing Tomb Raider. Do tell.

Since I’ve been a gamer for a long time, I suppose I should have thought about becoming a game composer sooner! But my career had taken me into public broadcasting. I’m classically trained as a musician and vocalist, and my first job as a composer was creating the music for a National Public Radio series called Radio Tales. The series host/producer Winnie Waldron hired me to compose the music for more than a hundred programs that adapted classic works of literature for the radio. It was a fun gig! But all the while, I never stopped playing video games. And then one day, I was playing Tomb Raider, and the music suddenly grabbed my attention. I remember the light bulb going off in my head. I convinced Winnie to make the big leap into the game industry with me, and it’s been a grand adventure ever since.

Your Top 5 favorite games as a kid, the ones you absolutely wore out:

I was a huge fan of the Final Fantasy series. Played those games endlessly! I remember spending tons of time with Crash Bandicoot. Loved Prince of Persia. Sunk huge chunks of playtime into the Civilization games. And of course, the Tomb Raider games hold a special place in my heart, for a lot of reasons.

Which musical instruments do you play?

I play a bunch of different instruments with varying degrees of proficiency, but I’m trained in keyboards and voice. The keyboard is the most useful for me, since it’s the instrument on which I compose.

How did you get your first composing gig?

I actually landed my first two video game composing gigs at the same time – God of War from Sony Interactive Entertainment, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory from 2K Games. Both jobs came out of meetings I took during the Electronic Entertainment Expo – an enormous video game convention and a great place to meet industry folks.

Once more, from your book: “What does a television or film composer need to know about creating a satisfying linear loop, or a dynamic mix based on vertical layering, or a set of music chunks for horizontal re-sequencing….” Okay, so what DOES make for a satisfying linear loop? It doesn’t sound like this is going to involve something as simple as major and minor chords.

You’re absolutely right! It’s a very intricate discipline, and it walks the line between intense creativity and complex technical/logistical procedures. A lot of those concepts will be discussed during my lecture this week at the Library, and I’m really looking forward to it!

A lot of music composition is about math, about chord and key arrangements, a linearity that goes from beginning to middle to end. Does that change here?

Traditional music composition always includes a beginning, middle and end… and sometimes that kind of music composition is necessary in games, too. When a game is telling a narrative, the music needs to be able to tell that story emotionally, and linear music construction lends itself to that task. However, when we’re creating music that accompanies gameplay, we tend to break down the music into lots of component parts that are manipulated by the game’s programming. For a gamer, the music just seems to be magically reacting to everything that the player is doing, while still sounding like a continuous composition with a satisfying emotional arc. But for the game composer, the music is deconstructed into lots of fragments that are designed to fit together in lots of different ways.

Can you tell us what your studio looks like and where it is? Are you watching the games while you compose, like we see music conductors doing while recording film scores?

Over the years my composition and recording space has grown and changed, mirroring my various interests and obsessions, until its current state as an eclectic and quirky conglomeration of both vintage and modern equipment. I love everything in there – it all suits my workflow and inspires me to be creative. My business is located in the New York City metro area. The studio is pretty comfortable and inviting. I have a space for live recording, and a separate room where I do my composition as well as all my mixing and other post-production work. And yes, I make sure that I’m watching video game footage while I’m working, so it’s usually on my largest video monitor mounted high over my workspace. I’ve worked with orchestras before, but those recording sessions take place on bigger soundstages, and then I bring the session recordings back to my studio for mixing and sweetening. Speaking of orchestras, my music from the Assassin’s Creed Liberation game is going to be performed by an 80-piece orchestra and choir as a part of the upcoming Assassin’s Creed Symphony World Tour, which kicks off this June 11th at the Dolby Theater in Los Angeles. Touring symphonies like this one are a great sign of how popular game music has become!

Do you typically score the entire game, or just parts of it?

I’ve composed all the music for entire games, such as Assassin’s Creed Liberation, The Da Vinci Code, Shrek the Third, and so on. I’ve also composed music as part of a team, on projects such as the six LittleBigPlanet games. Whether I’m hired as the sole composer or as part of a team, the business is pretty similar. I’m contracted to create a certain amount of music. The game’s development team briefs me on the technical specs. We discuss ideas for musical style. Then I get to work.

April 3, 2019

The Library Goes Gamer: Augmented Realities Mini-Fest

Gamers! The Library is all yours for the next three days.

Retro arcade games, a documentary, music and a new game composed in real time. That’s some of what’s up in our Augmented Realities Mini-Fest, put together by our very own David Plylar and the Library’s Music Division.

It starts Thursday night with a screening of “Reformat the Planet” in the Pickford Theater and winds up Saturday with rock-star composer Winifred Phillips (Assassin’s Creed Liberation, The Da Vinci Code, etc.) speaking in the Whittall Pavilion. The big deal on Friday is an audience-influenced, game-designing session by Rami Ismail, featuring a new, adaptive score composed by Austin Wintory. The #LOCArcade is Saturday.

Check back here tomorrow for a conversation with Phillips! Meanwhile, other people you’ll get to see:

Philippe Quint, violinist

Peter Dugan, pianist

Triforce Quartet

Bryan Mosley and Gene Dreyband, Pixelated Audio

Mark Gray and John R. Riley, Copyright Office, Library of Congress

David Gibson, Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress

Amanda May, Preservation Reformatting Division, Library of Congress

The full schedule is below.

Augmented Realities: A Video Game Music Mini-Fest

EVENTS

Thursday, April 4, 2019–7:00 pm [Film]

Reformat the Planet (NR, 82 mins)

Directed by Paul Owens

Pickford Theater (Tickets Not Required but Register for Reminder)

Reformat the Planet is a documentary about the first annual Blip Festival that explores the ChipTunes movement, in which composers create new electronic music using repurposed video hardware.

Friday, April 5, 2019–12:00 pm [Panel]

“Copyrighting a Cartridge: An Inside Look at Copyright and Video Games”

Mark Gray & John R. Riley, Attorney-Advisors, Copyright Office

Whittall Pavilion (Tickets Not Required but Register for Reminder)

Join us for a fun and informative look at interesting copyright issues related to video games. There will be some fascinating items on display as well!

Friday, April 5, 2019–8:00 pm [Special Event/Concert]

“Hi, Score! Introducing a Game to its Music”

Featuring Austin Wintory, Philippe Quint, Peter Dugan, Pixelated Audio and the Triforce Quartet

Coolidge Auditorium (Tickets Required)

Pre-concert lecture, 6:30pm:

“A Brief History of Video Game Music”

Bryan Mosley and Gene Dreyband, Pixelated AudioWhittall Pavilion (Tickets Not Required)

The Coolidge Auditorium will transform into a game creation lab as a new Library commission by composer Austin Wintory gets re-spawned as part of a video game score—all while you watch! First hear the new commission performed by violinist Philippe Quint and pianist Peter Dugan, and then hear it re-contextualized using interactive media. A new game is being designed by Rami Ismail just for this event, and we’ll get to see, hear and discuss how it all comes together. Bryan Mosley and Gene Dreyband of Pixelated Audio fame will join the conversation and provide some context for this dynamic process. Additionally, the Triforce Quartet will perform some classic tunes re-imagined for string quartet!

Saturday, April 6, 2019—10am-4pm [Interactive Display]

#LOCArcade, Mahogany Row and LJ-119

Tickets not Required

Saturday, April 6, 2019–11:00 am [#Declassified]

#Declassified: “Processing and Preserving Video Games”

David Gibson, Motion Picture, Broadcast and Recorded Sound Division

Amanda May, Preservation Reformatting Division

Whittall Pavilion (Tickets Not Required but Register for Reminder)

Amanda May and David Gibson from the Library of Congress will discuss the steps that the Library takes to collect, catalog and preserve video game content, focusing on the employment of Resource Description and Access (RDA) to describe video games in the catalog and the use of specialized hardware and software to forensically recover data from fragile digital media.

Check out this vintage blog from David Gibson to get a sense of the conservation issues in 2012: //blogs.loc.gov/thesignal/2012/09/yes-the-library-of-congress-has-video-games-an-interview-with-david-gibson/?loclr=blogmus

Saturday, April 6, 2019–2:00 pm [Lecture]

“The Interface Between Music Composition and Video Game Design”

Winifred Phillips, composer and author

Whittall Pavilion (Tickets Not Required but Register for Reminder)

Winifred Phillips speaks about her work as a composer in the video game industry, exploring the process of composing for video games, from concept to release.

April 2, 2019

From Ethnography to Feathers, Investigating Collections at the Library

How can I tell stories about ancient artifacts when their parts are scattered in different places in a library? I take the example of ethnographers: When they are doing fieldwork to decipher a given society, they study the general culture along with specific items, such as photographs, personal letters, official documents and historical archives. They’re always looking for an “Aha!” moment that offers a bit of unique insight.

Giselle Aviles examining a miniature feather tunic from the Ica Valley of Peru, 12-13th century CE in the Preservation Research and Testing Division of the Library. William and Inger Ginsberg Collection, Library of Congress.

When I received the message that I was going to collaborate with John Hessler, the curator of the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Archaeology and History of the Early Americas — which includes Pre-Colombian Peruvian textiles and Mayan ceramics — I couldn’t believe it. No longer would I be appreciating early American artifacts through the exhibit cases of a museum. I would be close to them, studying them, feeling them.

Photograph in UV light of the Ica Feather Tunic. Analysis by Tana Villafana, Senior Scientist in the Preservation Research Division, and Giselle Aviles, Archaeological Research Associate

It’s been thrilling. The Kislak collection encompasses, for example, a diversity of chuspas, a Quechua word for a hand-woven pouch used to carry coca leaves. When looking for the first time at the Peruvian textiles, donated by William and Inger Ginsberg, I found myself imagining the stories behind them. What conversations could have taken place? What social relationships would have developed? Did many families weave? Why did they chose those specific colors and patterns? Did a preferred location to weave exist, such as at home or a workshop? What would the weaver’s space be like while the textile was being thought through and produced?

My methodology over the next few months will be to grasp the symbols, colors, and feelings of objects in the Kislak Collection and relate them to other items in the library, such as rare books, manuscripts and maps. Working with archaeological artifacts in an ethnographic way is exciting, and there is not a single day when I don’t learn something new. I have the objects in front of me. I sit in the cold vault where the artifacts are temperature protected and, alone, I talk with them. How can an ancient life be thought about through a specific artifact? These are questions that I hope to ponder during my research time at the Library and discuss in my Gallery Talks in the Exploring the Early Americas Exhibit.

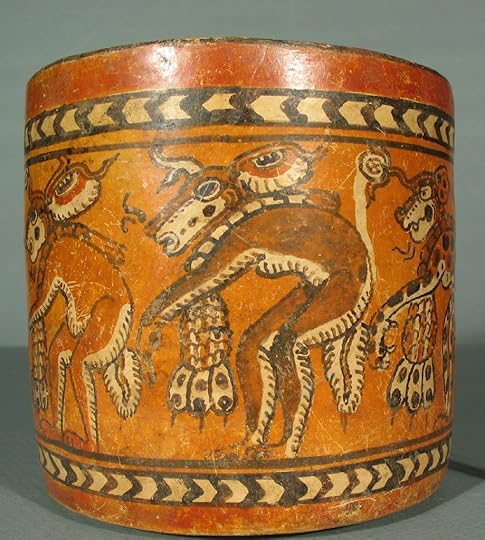

Maya Ceramic Vase with Animal Way Dancers. One of the many ceramic pieces being investigated by Giselle Aviles. Jay I. Kislak Collection, Library of Congress.

April 1, 2019

Inquiring Minds: Peter Carlson Brings History to Life

Photo by Shawn Miller

Peter Carlson is the author of three books of history, drawing much of his research from the Library’s collections. Each book mines a different era. “Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy” is about two intrepid Civil War reporters; “K Blows Top” details Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s tour of America in 1959; “Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood” is the tale of the cowboy and silver prospector who became a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World in the early 20th Century. A native New Yorker, Peter studied journalism at Boston University. Now a columnist for American History magazine, he has previously written for the Boston Herald American, People magazine and The Washington Post.

During his 22-year run at the Post, he was known for writing colorful yarns about cheerfully outrageous people. Or, as he describes it on his website: “…stories about cops and murderers and crooked pols and Arnold Schwarzenegger and the United States Senate and striking coal miners and Jerry Falwell, and wounded soldiers and a Virginia militia group and the 2004 Olympics and the guy who created Foamhenge, a life-size replica of Stonehenge carved out of Styrofoam.”

How did you get started writing?

I started writing shortly after I started reading Dr. Seuss books. I tried to write a Dr. Seuss book, complete with zany rhymes. A few years later, I created handwritten newspapers on looseleaf paper, filled them with fake news, and sold them to my neighbors for a nickel. Later, I worked on my high school newspaper, my college newspaper and then real newspapers. I’m pretty much useless for any activity except writing.

Your work so often features offbeat, larger-than-life characters. Is this a conscious choice? What sort of anecdotes are you looking for, and how do you know when you come across a great one?

I’ve always loved off-beat characters, perhaps because my father, who climbed poles for the Long Island Lighting Company, hung out with guys called “Rotten Socks” and “Shot-in-the Head.” They were wonderfully entertaining and funny. My father’s highest praise was to call somebody “a real character.” When I’m searching for a story, I look for “a real character”— or, better yet, two of them who are having some kind of conflict. Nikita Khrushchev, star of my book “K Blows Top,” is that kind of fabulous character, which made his 1959 tour of America—the topic of the book– a comic extravaganza.

How did you hear about Junius Browne and Albert Richardson, and how did you turn that into a book?

I got a job at American History magazine in 2011, which was the 150th anniversary of the start of the Civil War, so I suggested to an editor that we run a newspaper story from the war in every issue. He said, “That would be a good idea, but Civil War journalism was really lousy.” I thought, “Is that true?” So I read a book on Civil War journalism and came across a short version of the story of Junius and Albert’s amazing adventures covering the war for the New York Tribune and getting captured by Confederates. I followed the footnotes and learned that both men had written memoirs of their adventures, so I thought, “Aha! Primary sources!” Of course, I had to do a lot of other research, much of it in the Library of Congress, reading newspapers of the era and books about the battles they covered and the prisons they endured before they finally escaped.

How do you use the Library in your research? What’s your favorite story about finding something in the Library?

Mostly I read old newspapers in the newspaper reading room in the Madison Building, and old books in the fabulous Main Reading Room. But I’ve also ventured into the Rare Book Room and the Performing Arts collection.

When I was researching the book on Junius and Albert, I learned that while they were locked in a Confederate prison in Richmond in July of 1863, the Union prisoners celebrated the news of Grant’s victory at Vicksburg, which they read about in Richmond newspapers. I wondered: “Why didn’t they celebrate the victory at Gettysburg, which happened at the same time?” So I studied the Richmond newspapers that the prisoners were reading—the Library has the actual papers; they’re not on microfilm! — and I learned that the Richmond newspapers reported that the Confederates had won the battle of Gettysburg. “OUR ARMY VICTORIUS AT GETTYSBURG,” read the headline in the Richmond Examiner, “THE YANKEE ARMY RETREATING.” That’s why the Union prisoners weren’t celebrating Gettysburg—they thought they’d lost. And I never would have known that if not for the good old Library of Congress.

Any advice for researchers just getting started? The Library is so huge that it can seem intimidating.

Ask the librarians for help. They are incredibly knowledgeable and almost always eager to help you find stuff. Also, if you’re working in the Main Reading Room, there’s a tendency to get caught up in your work and forget that you are in the most beautiful room in Washington. Remember to pause periodically and gaze up at that magnificent dome. It’s such a privilege to work there. Enjoy it.

Lastly, what are you working on now?

I’m writing a column called “American Schemers” for American History. Each column is the story of a great American hustler. I write about con men, crooked pols, shameless hucksters, wayward preachers– colorful rogues of every stripe. The silver-tongued scam artist is an American archetype and the Library of Congress is chock full of their stories.

March 29, 2019

Pic of the Week: Harriet Tubman, Seen as Never Before

The restored Emily Howland Album featuring an a previously unknown portrait of Harriet Tubman, March 25, 2019. Photo by Shawn Miller.

It was a magic moment: Harriet Tubman, revealed as a woman in the fierce prime of her life. In a March 25 ceremony, Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and National Museum of African American History and Culture Director Lonnie Bunch unveiled the photo album of abolitionist Emily Howland, featuring a previously unknown portrait of Tubman. The photograph, taken around 1868, captures Tubman in her mid-40s, years younger than most surviving photographs that show her late in life. Here, then, is the leader of the Underground Railroad as she would have appeared to her followers during the 19 trips she made into slave states, leading some 300 enslaved people to freedom, including her aged parents. She also served as a Union spy during the Civil War. The photograph, purchased by the Library and the Smithsonian, is on display in the NMAAHC.

March 28, 2019

Opening Day! A Video Tour of Library’s Baseball Americana

Major League Baseball starts today, which makes it the start of spring, never mind the official calendar. We remind you that your friendly national Library is just a long fly ball from Nationals Park, where the Nats open today against the New York Mets.

If you haven’t made it to our Baseball Americana exhibit, it’s going strong till July 27. You can see all sorts of early gloves, uniforms and bats; check out historic documents such as Branch Rickey’s 1963 scouting report on Hank Aaron (“…one of the greatest hitters in baseball today….[but] frequently acts frozen on pitches”); and get your picture taken as if on a baseball card.

In between innings, here’s a quick video tour. We hope to see you at the ballpark … and at the Library.

{mediaObjectId:'85183701D21B01D6E0538C93F11601D6',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

March 27, 2019

Branch Rickey Crowdsourcing Project: It’s Outta Here!

This is a guest post from Lauren Algee, LC Labs Senior Innovation Specialist.

[image error]

LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, [Reproduction number e.g., LC-L9-60-8812, frame 8].

Just four months after the Library partnered with the public to transcribe the papers of baseball icon Branch Rickey, volunteers have transcribed all 1,926 pages of Rickey’s scouting reports, making them available for digital research just in time for Major League Baseball’s opening day.These community-created transcriptions allow for keyword search and on-line scholarship, opening new avenues for baseball fans and researchers. The completed data is also available as a bulk download from LC Labs. Our volunteers showed amazing hustle in finishing so quickly. Their work now makes it possible for data research, including text analysis examining Rickey’s diction, or looking for patterns in names, places, or dates. Analyzing the texts as data can also reveal patterns and prompt new questions. We offer a respectful tip of the cap to our volunteers.

No one encapsulates baseball’s history quite like Rickey (1881–1965), a former player and manager who became an innovative baseball executive and part-owner over a career spanning nearly 60 years. He established the farm-league system, but is most often remembered for bringing Jackie Robinson into pro ball in 1947, breaking the Jim Crow-era color barrier. Famed sportswriter Red Smith summed him up this way: ”player, manager, executive, lawyer, preacher, horse-trader, spellbinder, innovator, husband and father and grandfather, farmer, logician, obscurantist, reformer, financier, sociologist, crusader, sharper, father confessor, checker shark, friend and fighter.”

The Library’s Rickey papers are extensive, including 29,000 items of correspondence, photographs, memoranda, speeches, and more. His scouting reports, compiled during the 1950s and 1960s, show him to be an astute, if caustic, judge of talent. Some resemble modern-day tweets in their brevity and wit. After watching a 1953 minor-league double-header, he summed up 29-year-old Bob Wakefield, who’d been bouncing around the minors for half a dozen years, in one sentence: “I think he’s a good man to get rid of.”

Reference guides show Wakefield was cut that season, and never played pro ball again.

[image error]

Rickey’s tart, one-line summation of Bob Wakefield.

At the Library, Rickey’s scouting reports were scanned in 2018 but could not easily be turned into searchable text. Many of the documents are grainy photocopies, including forms and tables, which stymied word-recognition software.

So, on Oct. 24, 2018, the Library launched By the People, a web-based crowdsourcing program, to harness public energy in transcribing the papers of Rickey and several other historical luminaries. The work these volunteers do improves the search, access, and computation of our digitized collections. Other By the People campaigns include letters to Abraham Lincoln, the diaries of Clara Barton, the personal papers of Mary Church Terrell and writings by disabled Civil War veterans. Volunteers have transcribed more than 10,000 pages so far.

[image error]

Word cloud made from most frequent words in Rickey’s scouting reports. Larger size indicates more frequent use.

To illustrate some of the research uses that can now be carried out on Rickey’s collection, the By the People team used Voyant Tools, a web-based text analysis environment, to make some initial forays into the data.

We found that one set of data — composed of Rickey’s memos — is comprised of 1,747 transcriptions, including 176,308 words and 6,881 unique words. In these documents, Rickey averaged 13 words per sentence. As illustrated above, his most used words were “good” (1902), “ball” (1841), “branch” (1122), “rickey” (1110) and “curve” (1037). As Wakefield discovered, Rickey using “good” in an evaluation did not necessarily mean “good” things for the player.

Many of the documents from the early 1960s, when Rickey advised the St. Louis Cardinals. These notes included a tag, “cc: Bing Devine,” the team’s general manager from 1957 to 1964, 266 times, thus illustrating Rickey’s close ties to top management.

But our analysis of “bing” also revealed a surprise – one instance of “Bing Crosby.”

This came from a 1951 report on pitcher Vern Law that Rickey put together for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Rickey was almost as unimpressed with Law as he was with the hapless Wakefield. He said the young player was overpaid by half and that he should be sent to a training camp in Florida. Law would either become a better pitcher or he “won’t be worth very much.” Still, Rickey knew there were personalities involved, and that Law had friends in high places. His evaluation adds: “His salary should be reduced back to $5,000 for ’52, but it may be unadvisable because of Senator Walker and particularly Bing Crosby whose final effort secured the player.”

[image error]

Branch Rickey Papers: Baseball File, 1906-1971; Scouting reports. Manuscript Division.

After Rickey’s evaluation, Law left baseball, entering the military for two years. But unlike Wakefield, he wasn’t finished.

Nine years later, the Milwaukee Journal ran an article in which Law’s mother described a long-ago phone call from the famous crooner, then part-owner of the Pirates, in which he had recruited her son for the team. Crosby’s friend, Herman Welker, later a U.S. Senator for Idaho, had seen Law play as a high school senior and had recommended him to Crosby. Thus, his youthful appearance before Rickey all those years ago.

It was a good time to run a piece on Law’s path to the majors.

Two days later, Law was the starting pitcher in Game 1 of the 1960 World Series, facing the powerhouse New York Yankees, who had won the Series eight times in the past 13 seasons. It would become one of the most famous of all the Fall Classics, and Law was a key figure.

Right off the bat, Law gave up a first-inning homer to Roger Maris, the American League MVP, but won the game, 6-4. The Yankees crushed the Pirates the next two games, 16-3 and 10-0. Desperate, the Pirates turned again to Law in Game 4. He turned in another gem, cutting down the powerhouse Yankees, 3-2.

The Pirates won the series with a Game 7, walk-off home run by Bill Mazeroski, one of the legendary moments in MLB history. The Yankees had outscored the Pirates 55-27, but lost the Series — largely because Vern Law, Bing Crosby’s pick, shut them down twice.

Rickey’s reaction, we regret to report, is lost to history.

March 26, 2019

Mary Ann Shadd Cary: Trailblazer for Feminism, Freedom

This is a guest blog by Jennifer Davis, a collection specialist in the Law Library’s Collection Services Division. It is has been slightly edited from her original blog.

[image error]

Mary Ann Shadd Cary residence, Washington, D.C. (photo by J. Davis)

Mary Ann Shadd Cary was a 19th Century African-American feminist, lawyer, anti-slavery crusader and newspaper publisher. She was also, as our colleague Jennifer Davis pointed out recently on a In Custodia Legis blog, a polymath who challenged the definition of what it meant to be a woman in her era. Even better, she often won those challenges.

We’re recounting a brief bit of that history here, in part because it’s Women’s History Month, but also because Cary seems not to be as widely remembered as many of her trailblazing contemporaries. This is perhaps because she was an “iconoclast” who “annoyed people by refusing to be deterred or to tone down her message,” Davis notes. At the age of 25, she wrote Frederick Douglass, “We should do more and talk less.” She wasn’t kidding, and she wasn’t here for nonsense.

She was born Mary Ann Shadd in Wilmington, Del., on October 9, 1823, to free parents. Although the population of free blacks was high in Delaware at the time, educational opportunities for black children were almost nil. Her parents left in 1833, moving to West Chester, Pa., where she attended a Quaker boarding school until she was 16. She then began teaching school, first in New Jersey, and later in Pennsylvania, Delaware and New York City.

When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, she moved to Windsor, Canada — just across the Detroit River from, well, Detroit — to join a community of expatriate African Americans. While there, she taught at an integrated school and wrote the pamphlet Notes of Canada West, urging black Americans to emigrate north as she had. She was the first black woman to publish a weekly newspaper, launching the abolitionist The Provincial Freeman in Chatham, a small city east of Windsor, in March 1853. She did everything at the paper — wrote, reported, edited, sold ads and subscriptions – all while keeping her day job as a teacher. In 1855, she traveled to Philadelphia to speak at the Colored National Convention, dazzling the crowd with her gift for oratory.

She married Thomas Cary, who owned several barbershops in Toronto, the following year. He commuted the 180 miles from Toronto to Chatham, trying to make ends meet, but the couple struggled financially. They had a daughter, but his health was failing. He died in 1860, when she was pregnant with their second child. The paper finally collapsed.

She was now the single mother of two young children, nearing 40 — and just getting started. When the Civil War ignited, she was appointed as a recruiting officer for the U.S. Army, the first black woman to be so designated. She moved to Indiana to enlist African American soldiers in the war effort. After Appomattox, she moved to D.C., settling into a rowhouse at 1421W St. NW, and enrolled in Howard University’s Law Department. She graduated in 1870, now in her late 40s, becoming the first African-American woman to get a law degree in the United States.

[image error]

Mary Ann Shadd Cary Residence sign (photo by J. Davis)

Gaining steam, she joined the growing women’s voting movement. Fellow activists such as Douglass and Susan B. Anthony testified before Congress, and she was one of 600 citizens who signed a petition that suffragists presented to the House Judiciary Committee, arguing for a woman’s right to vote. She joined the National Woman Suffrage Association. Later in the 1880s, she founded the Colored Women’s Progressive Franchise Association.

In her final years, Cary used her degree to help family, friends and neighbors in her D.C. neighborhood deal with legal issues. She continued to work for women’s rights and for equal rights for all black Americans. She died in June 1893. Douglass once wrote of her, “We do not know of her equal among the colored ladies of the United States.”

It was, by any measure, a remarkable life.

You can read more about her here:

LA2325.C34 Bearden, Jim and Linda Jean Butler. Shadd: the Life and Times of Mary Shadd Cary.

E185.97.C32 F47 2003 Ferris, Jeri Chase. Demanding Justice: A Story About Mary Ann Shadd Cary.

E185.97.C32 R48 1998 Rhodes, Jane. Mary Ann Shadd Cary: The Black Press and Protest in the Nineteenth Century.

March 25, 2019

Suffragists in Song

Our colleague Cait Miller published a pair of delightful posts about songs in the women’s suffrage movement over on the “In the Muse” blog recently, the most recent of which is here. But it being Women’s History Month, we just had to know more about one of the sheet music covers she featured — the one with the remarkable title, “She’s Good Enough to be Your Baby’s Mother and She’s Good Enough to Vote with You.”

[image error]

“She’s Good Enough to Be Your Baby’s Mother” by Herman Paley (music) and Alfred Bryan (lyrics). New York: Jerome H. Remick & Co., 1916. Call number M1665.W8 P

Wait. Child production equals…voting rights?

Published in the winter of 1916,when the suffrage movement was a hot-button political issue, the song (and its sheet music, featuring perky mom and radiant baby) are a nifty bit of insight into an earlier version of American pop culture. The song, after all, at face value, is an appeal to the male idea of a woman’s worth, as if women had no other merit than what men might deign to assign them.

First, while it might not have been the “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” of its day, the song nonetheless made waves, as it fell into a well-established social groove. Suffrage songs had been quite the thing during the decades-long struggle for women’s voting rights. The first National Women’s Rights Convention was in Massachusetts in 1850. The next year at a convention in Ohio, Sojourner Truth made her immortal “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech. Icons such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the American Equal Rights Association a little over a decade later, and years of progress, setbacks (and no small amount of infighting) followed. Songs were routinely written for and sung during these meetings, usually spirited affairs about uplift and equality. The Library holds hundreds of them in its collections.

By the middle of the second decade of the 20th century, the Progressive Era was well established, and suffrage songs had left the meeting halls and entered pop culture. Several states had already passed suffrage laws — Colorado, Utah, Idaho and California among them — but the federal government had not. As you might imagine, protest marches drew thousands.

One of these marches, pictured below, took place in New York in late October, 1915. The careful eye will note that while nearly all the marchers are women (wearing white, to represent the movement), the overwhelming majority of the street-level viewers are men.

[image error]

New York City suffrage parade Oct. 23, 1915. LOT 11052-4. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

New York in this era was also the home of Tin Pan Alley, the hothouse of American popular music. Novelty songs were all the rage, so how could such a huge hometown protest, and a national issue, go ignored by the industry?

Three months after the big parade in New York, the sometimes songwriting team of Alfred Bryan (lyrics) and Herman Paley (music) came out with, “She’s Good Enough…”

These were big-time players. Bryan, a Canadian who had moved to New York in the 1880s, was hitting his mid-career stride. He had written “Peg ‘o My Heart” for the Ziegfeld Follies a few years earlier — one of the most memorable songs of the era — and was a charter member of The American Society for Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1914. Today, he’s in the Songwriters Hall of Fame for a career that included Broadway and Hollywood. Paley, the composer, was a Russian immigrant who also had a long career in the music industry in New York and L.A.

They combined for a bouncy, vaudeville-like melody that rolled along, letting you know you’re supposed to laugh. They’re having good-natured fun, by all appearances:

She’s good enough to love you and adore you

She’s good enough to bear your troubles for you

And if your tears were falling today

Nobody else would kiss them away

She’s good enough to warm your heart with kisses

When you’re lonesome and blue

She’s good enough to be your baby’s mother

And she’s good enough to vote with you

“This is an example of popular music that draws upon women’s suffrage as a topical theme,” says Miller, a Music Reference Specialist at the Library. “It was not intended for suffrage meetings or parades.”

Further evidence of its impact is that it was recorded by Anna Chandler, a mezzo-soprano and an established star. In 1912, the Edison Phonograph company ran an ad in the Saturday Evening Post listing her (she’s on the far right, middle row, wearing what appears to be flower-covered hat), alongside stars such as Sophie Tucker, John Philip Sousa and the wildly popular Billy Murray.

Saturday Evening Post, Jan. 13, 1912, p. 36. Includes portraits of Sophie Tucker, Stella Mayhew, Nat M. Wills, Victor Herbert, Lauder, Sousa, Sylva, Slezak, Carmen Milis, Anna Chandler, Ada Jones, and Billy Murray. Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-99979 (b&w film copy neg.) Call Number: Illus. in AP2.S2 [General Collections]

And, of course, on Aug. 16, 1920, the 19th Amendment passed. Women — mostly white women, as a practical matter — gained the right to vote.[image error]

“She’s Good Enough to Be Your Baby’s Mother” by Herman Paley (music) and Alfred Bryan (lyrics). New York: Jerome H. Remick & Co., 1916. Call number M1665.W8

Still, the song wasn’t done.

It lingered in the cultural memory, as comic relief and as reference to the period. It was anthologized in 1999’s “Respect: A Century of Women in Music” (Rhino), along with the likes of Judy Garland’s “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” Marian Anderson’s “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and Patti Page’s “The Tennessee Waltz.” Minnesota musician and songwriter Ann Reed included it in her 2007 show, “Heroes: A Celebration of Women Who Changed History and Changed Our Lives,” produced by Minnesota Public Radio. Denise Tabet, a Minneapolis-based actress, sang it live on stage, bringing a burst of laughter and applause from the audience when she hit the chorus – a century after Anna Chandler had done the same in a distant, different era.

March 23, 2019

Pic of the Week: Code Girls Reunion

[image error]

The Veterans History Project hosted a special reunion of World War II veteran “Code Girls,” March 22, 2019, at the Library of Congress. Photo by Shawn Miller.

More than 10,000 women were recruited by the U.S. Army and Navy as secret code breakers in World War II, working to decode enemy communications. Their story was finally, fully revealed in 2017’s bestselling, “Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II.” The Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress hosted a reunion on Friday, March 22. Here, “code girl” veterans Nancy Tipton and Katherine Fleming chat with author Liza Mundy, who told their story.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers