Library of Congress's Blog, page 70

July 26, 2019

Pic of the Week: Junior Fellows Edition

Anthony Lowe of the University of Maryland, a Junior Fellow at the Center for the Book, explaining his work during this week’s display.

The Library’s 2019 Junior Fellows Summer Internship Program showed off their most significant findings and research this week in a display that is the annual highlight of the 10-week program. This year, 40 graduate and undergraduate students worked across the Library’s divisions on projects as varied as women’s suffrage, transcultural teaching guides, and inventorying films from the Walt Disney Co. Here, Anthony Lowe of Lanham, Maryland, and a student at the University of Maryland, showcases his work at the Center for the Book. The Literary Story Map project entails creating a nationwide database that records each state center’s reading initiatives, literacy programs and writing workshops. The display will include an interactive database that guests will be able to use to find which literacy programs are supported in their state.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 25, 2019

Charles Manson and “Once Upon a Time….in Hollywood”

Manson on trial in Los Angeles. Sketch: William Robles. Thomas V. Girardi collection, Prints & Photographs Division.

This story is adapted from an upcoming issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Charles Manson scarcely appears in “Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood,” the new Quentin Tarantino film. But the Manson family’s murderous home invasions on the nights of Aug. 8 and 9, 1969, give the film its narrative tension, and Manson’s aura hangs over the entire film, as it should. The story of his band of hippies turned killers – mostly wayward young women with a penchant for drugs, sex and knives – has transfixed the nation for half a century, in a way that few other crimes ever have.

The slayings – seven people were butchered, including actress Sharon Tate, who was eight and a half months pregnant — were a horror show that brought the excesses of the decade into glittering focus. The nation, transfixed, looked at the killings and saw the larger society unraveling. Hippies, drugs, guns, celebrity, violence, racism, counterculture revolution. It all blew up into the madness of a man who wanted to ignite an apocalyptic race war by killing rich white people and framing black people for it.

[image error]

Front page of Los Angeles Times, Dec. 6, 1969, with headlines designed to generate street sales.

The Manson murders, Joan Didion famously wrote, ended the ‘60s. “Helter Skelter,” prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi’s frightening book about the killings, is still the bestselling true-crime book in U.S. history. All three of Manson’s female co-defendants were sentenced to death, likely the most women condemned to die in one incident in North American jurisprudence since the Salem witch trials in 1692. (All five death sentences in the case, including Manson’s, were later commuted to life in prison following a U.S. Supreme Court decision.)

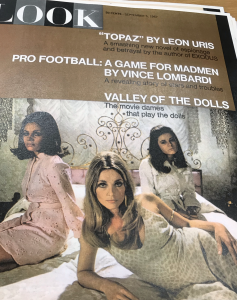

Sharon Tate, on the cover of Look magazine, Sept. 5, 1967. Look Collection, Prints & Photographs Division.

As the number of books, pop songs, films, documentaries and based-on novels blossomed over the years, Manson became the primogenitor of the “killer with something to say” trope, the idea that there’s this darkly intelligent madman who’s onto something about the quivering underbelly of the American dream. Like he was the Joker from Batman, brought to life. Reporters flocked to his jail cell for interviews. He was profiled on the cover of Rolling Stone in a 30,000-word story that dubbed him “the most dangerous man alive.” His image — greasy black hair, grungy beard, the “X” he cut into his forehead before his trial — was emblazoned on T-shirts and posters. Guns N’ Roses recorded one of his songs. Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails made a music video in the house where Manson’s followers killed Tate and her friends. Rocker Marilyn Manson used the killer for half of his stage name.

“I am what you made of me and the mad dog devil killer fiend leper is a reflection of your society,” Manson said after his conviction. “Whatever the outcome of this madness that you call a fair trial or Christian justice, you can know this: In my mind’s eye my thoughts light fires in your cities.”

He died in prison in 2017, at age 83.

Manson’s hold on the national imagination is preserved in the Library in several ways – courtroom sketches, books, newspaper archives, recordings – the most notable of which is the iconic drawing by the legendary courtroom artist William Robles. Robles spent every day of the nine-month trial sitting a few feet away from Manson, who, as he remembers, “terrified people.” Once, when Robles accidentally knocked over his sketching materials, making a clatter, he looked up to see Manson suppressing a giggle, playfully running one index finger down the other: The “shame on you” gesture.

“I could see how people were attracted to him,” Robles said in a recent interview. “He had an appeal, a warmth.”

It’s not as crazy a contradiction as it sounds.

Since the dawn of civilization, human beings have killed one another, often for reasons that can neither be clearly articulated nor understood, and this violent mystery goes to the heart of human nature. Who are we? What are our ultimate taboos, and how do we respond when these are violated? Crime, writ small or large, can therefore become a shorthand, a brutal slash of insight, into the society that spawns it.

The first lines of Homer’s “The Iliad” — the foundational epic of Western literature, composed about 2,800 years ago – describe the murderous “anger of Achilles” that sent many a brave soul “hurrying down to Hades.” The biblical Book of Genesis, another cornerstone of Western culture, says that when the population of the Earth was four, Cain killed Abel, reducing it to three.

The Library’s holdings on the meanings of murder range from ancient manuscripts to Wild West ballads to most everything in between. Some of these reflect the low arts of the “penny bloods,” the wildly popular Victorian-era serial stories that presaged today’s tabloids. Others achieve the status of high art, such as Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood,” the 1966 story of a multiple murder in Kansas that helped create the true-crime-as-literature-and-social-commentary genre.

[image error]

Harry Truman, then a U.S. Senator from Missouri, lets U.S. Vice President John Nance Garner handle Jesse James’ guns. Feb. 17, 1938. Photo: Harris & Ewing. Prints & Photographs Division.

The roots of this run deep in the American bloodstream. After the Civil War, the “Wild West” became a mythological landscape, a place where murder, blood and cruelty became a romantic notion. Jesse James, a Missouri-born bank robber and killer, became a cultural icon. Nearly a century after James was gunned down, President Harry Truman, a fellow Missourian, acquired his pistols and playfully posed with them – murder weapons as presidential guffaws.

“It’s always been an American theme to make heroes out of the criminals,” Johnny Cash, who himself made a career from songs of outlaws and prisons, told Rolling Stone in 2000. “Right or wrong, we’ve always done it.”

But it was only after Capote’s lyrical tale of murder in rural Kansas that Americans began seeing nonfiction literature and serious art as appropriate forums with which to address the nation’s violent culture without the gauze of fiction. The “New Journalism” Capote and others practiced on crime reporting became so influential that, today, we take it for granted. Pulitzer Prizes, National Book Awards, Academy Awards – all have all been given to tales of true crime. In 2016, ESPN Films described “O.J.: Made in America,” its Academy Award-winning, eight-hour documentary about the 1990s O.J. Simpson murder trial as “the defining cultural tale of modern America – a saga of race, celebrity, media, violence, and the criminal justice system.”

They might well have been describing the Manson case half a century earlier. Robert Kirsch, the L.A. Times book editor, reviewing “Helter Skelter” upon publication, seized on the crime’s significance. The book, and others like it, he wrote, were attempting to understand the frightening era in which they were living: “To accept these (killings) as simply symptoms of the malaise of the times,” he wrote, “is to abandon the obligations of civilization to rationally address even the most irrational and fearful events.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 23, 2019

Eisner Winner! Library’s “Drawn to Purpose”

“Drawn to Purpose,” the Library’s Eisner Award-winning book. Published by the University Press of Mississippi in association with the Library of Congress.

“Drawn to Purpose: American Women Illustrators and Cartoonists,” a lavishly illustrated study of the field written by Library curator Martha H. Kennedy, won the 2019 Eisner Award for the Best Comics-Related Book at San Diego’s Comic-Con International this weekend, a win for the Library and the University Press of Mississippi, which worked together to publish the book.

The Eisners, often nicknamed the Comic Book Oscars, recognizes the best in the comics industry in 31 categories, and Comic-Con in San Diego is the world’s premier comics festival, drawing more than 130,000 fans from around the globe. Kennedy was stunned to hear her name called during the awards ceremony.

“It’s pretty amazing,” she said. “I really was not expecting that I would win. I had a sense of the competition. It was a wonderful surprise.”

“Drawn to Purpose,” selected above four other finalists, won in a field that recognizes non-fiction work about the world of comics. The book, which was the subject of an exhibition at the Library in 2018, documents the role women have played in American newspaper comic strips, magazine illustrations, books, advertising and in political cartoons from the late 19th century to today. The book features 250 illustrations, covering the work of more than 80 women, including works as varied as the lush illustrations of Elizabeth Shippen Green in the early 1900s to the biting, witty works of Roz Chast, a staff cartoonist now working at the New Yorker. It draws almost entirely on the Library’s holdings in the Prints & Photographs Division, which has been collecting American graphic art since 1870.

[image error]

Caroline Durieux. “Bourbon Street, New Orleans.” 1943. Lithograph. Published in “Caroline Durieux: 43 Lithographs and Drawings,” Louisiana State University Press, 1949. Courtesy of Louisiana State University Press. Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Kennedy, with masters’ degrees in art history and library sciences, joined the Library 19 years ago. She started on the book around 2010, impressed by the Library’s holdings in the “Golden Age” of illustration (1880-1930). Though some of the work done by women were relatively well-known in this period — Jessie Willcox Smith, who illustrated “The Water Babies,” among dozens of other books; and Mary Hallock Foote, with her drawings of life in the American West — many more had faded into obscurity.

“I really believed in developing the work we had by women cartoonists and illustrators,” she said. “I felt they were underrepresented and I thought their voices were important. I felt their work had been left out.”

[image error]

Elizabeth Shippen Green. “Life was made for love and cheer,” 1904. Watercolor, charcoal. Published in “The Red Rose,” Harper’s Magazine, September 1904. Cabinet of American Illustration. Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The project took shape over the past decade, as Kennedy worked with the Library’s publishing office to turn the manuscript — and its 200-plus illustrations — into book form. The resulting work covers the eras of early cartooning in newspapers, when women were just beginning to enter the workplace. It documents the Depression when Marjorie Henderson Buell’s “Little Lulu” comic became a sensation. It finishes in the 21rst century of today, when, among many others, Lynda Barry has had a multi-platform career with “Ernie Pook’s Comeek” and nearly two dozen books.

“Women have become leaders in the world of contemporary illustration, producing best-selling works, winning top prizes and becoming industry powerbrokers,” Kennedy writes in the introduction, “a far cry from when they fought to get into print or gain entry into the very organizations that would later honor them with major awards.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 22, 2019

New: Omar Ibn Said Story Map

A portrait of Omar Ibn Said around the 1850s. Photo courtesy of Yale University Library. Opening image of the Omar Ibn Said project.

When the Library’s Omar Ibn Said Collection was put online earlier this year, the multi-national, multi-lingual story presented a challenge: How best to tell Said’s incredible journey? Born into wealth in an area known as Futa Toro (in modern-day Senegal) around 1770, he was an educated and respected man in his early 30s, a devout Muslim, when he was taken prisoner during a regional conflict and sold into slavery. He survived the middle passage in chains, was enslaved on a South Carolina plantation, escaped, but was recaptured in North Carolina. His eventual owners, a politically prominent family, treated him as a special case. He spent his last years as a well-regarded curiosity, often in touch with scholars. He died in 1863, still enslaved, during the Civil War.

Today, his 15-page, handwritten memoir — “The Life of Omar Ibn Said” – written in 1831, is the only known slave autobiography written in Arabic in the United States. It’s a window into a little-known aspect of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. At the Library, it is the centerpiece of a 42-document collection that fills out some of his life and the era in which he was subjugated.

Given this complexity, Benny Seda-Galarza, a public relations specialist in the Library’s Office of Communications, wanted to tell the tale with a Story Map, a multi-media platform that incorporates narrative storytelling, video, photography, maps, graphics and documents into a single interactive story. The result, “Educated and Enslaved: The Journey of Omar Ibn Said,” came out earlier this month. In June, the Veterans History Project used the same software to create “D-Day Journeys: personal geographies of D-Day veterans, 75 years later,” to tell the intimate stories of four soldiers who fought on that momentous day. These are two of the nine Story Maps that the Library’s staff have built since the projects began in 2018. Others include “Behind Barbed Wire,” about the newspapers that Japanese-Americans produced while in internment camps during World War II; “Maps That Changed Our World,” about the Library’s trove of historic maps; and “Incunabula,” about the history of printing in Europe during the transitional years of 1450-1500.

“We’re always trying to engage our users in a more creative way,” said Seda-Galarza, “and this enabled me to use copy, photos, video and graphics all in one place.”

That synthesis of material can be challenging, particularly since the Library is the largest storehouse of information in world history. That data – more than 165 million items, only a third of which are books — is spread over divisions, collections and databases. Some material might be digitized and easy to find online, or it might be on a tiny slip of paper, buried deep within a file in the Manuscripts Division. A key picture might be resting in a folder in Photographs and Prints, while an ancient manuscript might be in Rare Books. Nautical charts might be in drawer in Geography and Maps. Film? Try the temperature-controlled rooms, deep underground, at the Library’s Packard Campus of Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Va.

Megan Harris and Samantha Meier in the Veterans History Project headed up the “D-Day” project over a period of six months, digging up material “ranging from childhood photos to a pilot’s logbook, pen-and-ink sketches, an epic poem written in a foxhole a few weeks after D-Day, ticket stubs, and tourist maps” Harris says, to produce their quartet of stories. The “On D-Day” map alone, she notes, “took over 60 hours to complete.”

[image error]

Opening image of the Folklife Center’s “D-Day” project.

To produce the Omar Ibn Said project, Seda-Galarza worked with experts in six different divisions. Library photographer Shawn Miller shot and edited a video of the conservation work that went into preserving Ibn Said’s papers. The result pulls together 18th-century maps of Africa, 19th-century maps of the United States, quotes from Ibn Said’s autobiography, photographs of the man himself, different translations of his narrative, and letters written by (or to) Theodore Dwight, a founder member of the American Ethnological Society who played a key role in collecting Said’s work.

There’s also the final poignancy: Though Ibn Said fared much better under his North Carolina owners, he never regained his freedom. “I continue in the hands of Jim Owen who does not beat me, nor calls me bad names, nor subjects me to hunger, nakedness, or hard work,” he wrote, late in life. “I cannot do hard work for I am a small, ill man.”

Perhaps his physical stature was such at the time. But, more than 160 years later, his story lives in larger-than-life fashion.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

New: Omar Bin Said Story Map

A portrait of Omar Ibn Said around the 1850s. Photo courtesy of Yale University Library. Opening image of the Omar Ibn Said project.

When the Library’s Omar Ibn Said Collection was put online earlier this year, the multi-national, multi-lingual story presented a challenge: How best to tell Said’s incredible journey? Born into wealth in an area known as Futa Toro (in modern-day Senegal) around 1770, he was an educated and respected man in his early 30s, a devout Muslim, when he was taken prisoner during a regional conflict and sold into slavery. He survived the middle passage in chains, was enslaved on a South Carolina plantation, escaped, but was recaptured in North Carolina. His eventual owners, a politically prominent family, treated him as a special case. He spent his last years as a well-regarded curiosity, often in touch with scholars. He died in 1863, still enslaved, during the Civil War.

Today, his 15-page, handwritten memoir — “The Life of Omar Ibn Said” – written in 1831, is the only known slave autobiography written in Arabic in the United States. It’s a window into a little-known aspect of the trans-Atlantic slave trade. At the Library, it is the centerpiece of a 42-document collection that fills out some of his life and the era in which he was subjugated.

Given this complexity, Benny Seda-Galarza, a public relations specialist in the Library’s Office of Communications, wanted to tell the tale with a Story Map, a multi-media platform that incorporates narrative storytelling, video, photography, maps, graphics and documents into a single interactive story. The result, “Educated and Enslaved: The Journey of Omar Ibn Said,” came out earlier this month. In June, the Veterans History Project used the same software to create “D-Day Journeys: personal geographies of D-Day veterans, 75 years later,” to tell the intimate stories of four soldiers who fought on that momentous day. These are two of the nine Story Maps that the Library’s staff have built since the projects began in 2018. Others include “Behind Barbed Wire,” about the newspapers that Japanese-Americans produced while in internment camps during World War II; “Maps That Changed Our World,” about the Library’s trove of historic maps; and “Incunabula,” about the history of printing in Europe during the transitional years of 1450-1500.

“We’re always trying to engage our users in a more creative way,” said Seda-Galarza, “and this enabled me to use copy, photos, video and graphics all in one place.”

That synthesis of material can be challenging, particularly since the Library is the largest storehouse of information in world history. That data – more than 165 million items, only a third of which are books — is spread over divisions, collections and databases. Some material might be digitized and easy to find online, or it might be on a tiny slip of paper, buried deep within a file in the Manuscripts Division. A key picture might be resting in a folder in Photographs and Prints, while an ancient manuscript might be in Rare Books. Nautical charts might be in drawer in Geography and Maps. Film? Try the temperature-controlled rooms, deep underground, at the Library’s Packard Campus of Audio-Visual Conservation in Culpeper, Va.

Megan Harris and Samantha Meier in the Veterans History Project headed up the “D-Day” project over a period of six months, digging up material “ranging from childhood photos to a pilot’s logbook, pen-and-ink sketches, an epic poem written in a foxhole a few weeks after D-Day, ticket stubs, and tourist maps” Harris says, to produce their quartet of stories. The “On D-Day” map alone, she notes, “took over 60 hours to complete.”

[image error]

Opening image of the Folklife Center’s “D-Day” project.

To produce the Omar Ibn Said project, Seda-Galarza worked with experts in six different divisions. Library photographer Shawn Miller shot and edited a video of the conservation work that went into preserving Ibn Said’s papers. The result pulls together 18th-century maps of Africa, 19th-century maps of the United States, quotes from Ibn Said’s autobiography, photographs of the man himself, different translations of his narrative, and letters written by (or to) Theodore Dwight, a founder member of the American Ethnological Society who played a key role in collecting Said’s work.

There’s also the final poignancy: Though Ibn Said fared much better under his North Carolina owners, he never regained his freedom. “I continue in the hands of Jim Owen who does not beat me, nor calls me bad names, nor subjects me to hunger, nakedness, or hard work,” he wrote, late in life. “I cannot do hard work for I am a small, ill man.”

Perhaps his physical stature was such at the time. But, more than 160 years later, his story lives in larger-than-life fashion.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 19, 2019

Pic of the Week: Flickr Edition

Cinderella waltzes down the Great Hall staircase during a celebration of the film’s addition to the National Film Registry, June 20, 2019. Photo: Shawn Miller

The Library has featured some of its best historical photographs on a Flickr page for years, with more than 34,000 images in more than 45 albums. If you haven’t checked it out before, we hope you’ll take a minute now. Delights abound. Readers have flocked to see the 1930s-40s in Color album, with more than 3.9 million views. The 23,824 pictures in the News of the 1910s album have drawn more than 1.04 million views. There are also albums as specialized as Japanese Prints: Seasons & Places; Bridges; and WPA Posters. New pictures and albums go up all the time as more collections are digitized.

But starting today, there’s a new Flickr in town, and “Library Life” will take a decidely more contemporary approach, chronicling the Library’s exhibitions, events and happenings. Shawn Miller, the Library’s photographer, spends his days (and often nights) chronicling life at the world’s largest library, and his work will give you close-ups and behind-the-scenes access to some of the Library’s productions. The page goes live today, but Miller already has posted albums of the 2018 National Book Festival, Cinderella’s magic visit to the Great Hall and the Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote exhibit.

[image error]

Los Cenzontles performs Mexican American music during the Homegrown Concert Series in the Coolidge Auditorium, June 25, 2019. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Albums and events will be updated continually, so be sure to hit the “Follow” button. It’s your passport to seeing the Library like you never have before.

[image error]

The cast of “Queer Eye” looks over a collections display in the Whittall Pavilion, April 3, 2019. Photo: Shawn Miller

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 17, 2019

New! The National Book Festival Poster!

We’re delighted to repost this from our colleagues over at the National Book Festival. This year’s festival is on Aug. 31, and we’re looking forward to seeing you all there!

The poster for the 2019 Library of Congress National Book Festival has been unveiled! This year’s poster is the work of Marian Bantjes, a designer, illustrator, typographer and writer whose work is invested in beauty and structure and the intersection of words and graphics. She has been working in and around the design industry for 38 years, and is a member of Alliance Graphique Internationale.

Here’s what she has to say about her work on the 2019 National Book Festival poster:

I look for structure in any given project. For this, I started with the open book, on edge, with its pages radiating outward. I wanted something very sunny and bright, and so I built the structure further from these radiating lines with the idea of having words flowing out of the book. The book opens to a half-circle so I used this circle to form other parts of the structure, and divided the whole area up into sections based on this. I then developed a series of patterns used on the cupid-bow shape of an open book, and finally built some little flying books to accentuate the patterns and add a playful exuberance to the poster. The whole is a celebration and a joy.

Check out her work below, and download a high-resolution version of the poster here. You can also view and download all of the previous National Book Festival posters here. Then, make your plans for this year’s National Book Festival on August 31 in Washington, D.C.!

[image error]

July 15, 2019

Inquiring Minds: Rediscovering One of America’s Leading Songwriters

An excerpt in Gena Branscombe’s writing from her original “Pilgrims of Destiny” manuscript, held in the Library’s Music Division.

Mezzo-soprano Kathleen Shimeta stumbled upon Gena Branscombe (1881–1977) in the late 1990s when Shimeta was planning a Valentine’s Day recital. Branscombe, it turned out, had set to music Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s famous sonnet beginning “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” Delighted by the composition, Shimeta wanted to know more — including why she had never heard of Branscombe.

Thanks to a couple of decades of research since then, Shimeta is now an expert on the pioneering woman composer and choral director whose impressive body of work fell from public view in the years after World War II. Recently, Shimeta spent long hours studying handwritten scores and vocal parts held by the Library’s Music Division to help reconstruct a choral drama, “Pilgrims of Destiny,” Branscombe wrote 100 years ago this year. It was performed this spring by a choir of 100 at Clark University.

Tells a little about Gena Branscombe.

Gena Branscombe was a champion of American music. She composed art songs, piano works, chamber music, choral and instrumental pieces and a dramatic oratorio.

She studied and taught at the Chicago Musical College and at Whitman Conservatory in Walla Walla, Washington. She spent one year intensively studying piano with the Swiss-American pianist Rudolf Ganz, and she studied composition with Englebert Humperdinck in Germany.

Branscombe held national office for the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, the National League of American Pen Women, the Society of American Women Composers and the National Federation of Music Clubs. Through these organizations, she encouraged members to perform America’s music for their local concert organizations.

At age 40, Branscombe began conducting. She was conductor of the MacDowell Chorale in Mountain Lakes, New Jersey — affiliated with the MacDowell Colony, the artists’ retreat in Peterborough, New Hampshire — and she guest conducted choirs for women’s clubs and colleges. She also founded her own Branscombe Chorale whose members came from New Jersey, New York City and Connecticut.

[image error]

The June 22, 1929, issue of the Musical Courier reviewed the premiere of “Pilgrims of Destiny,” which had taken place a few days earlier in Plymouth, Massachusetts. It features a photograph of Branscombe. “Without doubt,” the review reads, “Gena Branscombe has produced an America[n] choral work of foremost rank.”

Why did you want to reintroduce Branscombe to the world?After discovering Branscombe’s art songs, I came to understand the era in which she composed. She was a successful woman composer during a time when woman composers were considered insignificant. Her songs are complex, have melodies that sing themselves and difficult piano accompaniments.

How did the Library acquire “Pilgrims of Destiny”?

The Library solicited Branscombe’s original orchestral score and orchestra parts for “Pilgrims” in 1960. The work had garnered the best-composition award from the National League of American Pen Women in 1928 and recognition from the Daughters of the American Revolution. The story takes place on the Mayflower as it sailed toward America in November 1620. The pilgrims are in despair, homesick, yet hopeful that their new country will appear on the horizon. Reconstruction of the orchestral score was necessary because the only complete hand-inscribed score is in fragile condition. We compared the Library’s score with the pencil workings of “Pilgrims” held at the New York Public Library.

[image error]

Kathleen Shimeta with two of Branscombe’s grandsons, Morgan Scott Phenix (left) and Roger Branscombe Phenix (right), on April 27, the day the reconstructed “Pilgrims of Destiny” was performed at Clark University.

How did your Branscombe research inform your understanding of the piece?

At the time Branscombe composed “Pilgrims,” her personal life had been shattered by the death of her 3-year-old daughter, Betty. In the depths of grief, she began composing this work.Her mourning and life are woven into her oratorio. Her faith in God as a healing force helped her overcome the tragic death of her daughter. There is a comforting, sweet lullaby and at another time an outburst by a mother who will never see her child again. Her harmonies are of a thick rich texture with key changes abounding as the sea unleashes its fury. The work concludes with a chorus of thankful jubilation to God.

Why do you think Branscombe was forgotten?

By the 1950s, Branscombe and her women-composer colleagues had become old-fashioned. Beautiful melodies were passé, while 12-tone and atonal music had become the fashion. In 1955, Branscombe’s music publisher notified her that her early music and her choral piece “Coventry’s Choir,” commemorating the bombing of Coventry Cathedral in World War II, had been destroyed. The probable cause was America’s economic recession at the time.

You’ve performed Branscombe’s work at the Library. Tell us about that.

For the Library’s celebration of the 100th anniversary of the MacDowell Colony, I was invited to perform in a recital featuring women composers of the colony, including Branscombe. She had twice been at the colony, written an article about its 50th anniversary and been a conductor for a MacDowell Chorale. Display cases in the lobby held pictures, music and letters of the three composers featured on the program. That day, my work on Branscombe’s music and life, my performing of her songs, the MacDowell Colony and the display items came together in one special moment.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 12, 2019

Pic of the Week: Girls Who Code Edition

[image error]

Girls Who Code students and leaders with members of Congress in the Library’s Great Hall, July 10, 2019. First row, standing on floor, from left: Rep. Lori Trahan (D-MA); Rep. Joyce Beatty (D-OH); Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA); Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL); Rep. Grace Meng (D-NY); Reshma Saujani, founder and CEO of Girls Who Code; Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV); Sen. Jacky Rosen (D-NV); Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY). One space to the right, in a black-and-white dress with a black blazer, is Marissa Shorenstein, board chair of Girls Who Code; at extreme right, Tiffany Cross, event moderator and the co-founder of The Beat DC. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The percentage of girls in K-12 computer science programs has hovered around 37.5 percent the past two years, an evaluation of school data conducted by the non-profit Girls Who Code found recently, despite legislation in 33 states that has sought, over a five-year period, to bolster computer science participation overall. Why aren’t more girls participating?

A bipartisan panel discussion to discuss that data — and other ways to boost the numbers of women in tech — was held Library this week, with several female members of Congress and about 150 girls from the organization attending the morning session.

GWC, a New York-based education and advocacy organization founded in 2012, has reached over 185,000 girls in all 50 states through its programs, which include after school clubs, a 7-week summer immersion program and even a series of YA novels, says Reshma Saujani, an attorney who founded the program after noticing the lack of girls in computer science classes.

“Almost 60 percent of our girls’ clubs are housed in libraries, where they feel safe, and where they are exposed to Librarians who are preparing them for the future,” said Saujani. “So the Library of Congress was a perfect fit. It was a a really powerful day.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

July 10, 2019

Inquiring Minds: Researching a Star of Silent Cinema

If you watched the Academy Awards in 2012, you probably remember “The Artist.” The mostly silent black-and-white French comedy-drama garnered 10 nominations and won five Oscars — including for best picture. But perhaps the most stunning thing about the film for many modern movie lovers was its revelation of the power of silent storytelling. For Giuliana Muscio, however, this was nothing new. She teaches film studies at the University of Padova in Italy and writes about film, mostly American. This spring, her research brought her to the Library, where she spent a week ensconced in the reading room of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division investigating the subject of her next book: Robert G. Vignola, an Italian immigrant to the U.S. who directed and acted in American silent movies.

[image error]

Giuliana Muscio

Tell us a little about yourself.

I was born in Friuli in northeastern Italy and studied at the University of Padova, where I earned a B.A. in contemporary history. I have an M.A. and a Ph.D. in film studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. I am the first woman to be nominated full professor of film studies in Italy. I have also been a visiting professor at UCLA and the University of Minnesota.

I work mostly on American cinema, from its origins to contemporary cinema. I write both in Italian and in English on film relations between the U.S. and Italy, American film history, Italian screenwriters and the influence of Italian stage traditions on American media. My Ph.D. dissertation, “Hollywood’s New Deal,” was based on primary research on Franklin D. Roosevelt and media. My most recent book, “Napoli/New York/Hollywood,” deals with the influence of the Italian diaspora on American film and the presence of Italian artists in American media. In 2018, I co-curated the exhibit “Italy in Hollywood” at the Museum Ferragamo in Florence, and I co-directed the documentary “Robert Vignola from Trivigno to Hollywood.”

[image error]

Marion Davies in her role in Vignola’s “When Knighthood Was in Flower” from a color ad in the fan magazine “Photoplay.”

Who was Robert Vignola?

Vignola was born in southern Italy in 1882 and emigrated to the U.S. with this family when he was 3. He grew up in Albany, New York, and started a career as a stage actor when he was quite young, later becoming involved in filmmaking in New York City. Starting in the 1910s, Vignola worked with Kalem Films, both as an actor and a director. In 1911, he travelled to Ireland, where he acted in the first films made there, and he also participated the making of “From the Manger to the Cross,” shot in Palestine in 1912. Between 1913 and 1916, he directed and acted in several shorts for Kalem, then he moved to Paramount, where he directed some of the most important actresses of the time — Pauline Frederick, Alice Brady, Marguerite Clark, Clara K. Young, Constance Talmadge and Ethel Clayton. In 1920, William Randolph Hearst hired Vignola at Cosmopolitan Productions, where he directed five Marion Davies films, including “When Knighthood Was in Flower,” promoted as the most expensive film made in the 1920s.

Between 1916 and 1925, Vignola was recognized as one of the main directors in American cinema, and his salary was among the highest. His career declined, however, in the mid-1920s when the film industry completed its transfer to the West Coast, where he moved only later, and the studio system became more structured.

Why is he important to cinema history?

My work on Vignola covers an underinvestigated period of American film history — 1914 to 1925 — and calls attention to other Italian filmmakers, such as Frank Capra, Gregory LaCava and Frank Borzage, fostering a new perspective on their influence on American silent cinema.

This wasn’t your first time at the Library. How were you introduced?

I know the Library and its motion picture collection well. It is indeed one of the best places to research American cinema. In 1974, I researched my Italian thesis, “Models and Stereotypes of Cold War American Cinema, 1945–1951,” at the Library, analyzing cultural changes in film genres and the relationship between Hollywood and Washington, for which I viewed about 100 films at the Library.

What was your experience this time around?

I was not aware until recently of how rich the collections are for the study of early silent cinema. For my Vignola research, I was able to see six of his films or fragments of them, among a total of only 20 extant titles (or excerpts), including shorts. I found synopses of some Kalem shorts in the copyright deposit files; I accessed a rare publication on the making of “From the Manger to the Cross”; and I consulted collections of reviews. I especially appreciated being able to read the magazine “Dramatic Mirror” and issues of the film-fan magazine “Photoplay.” Although some of these materials may be available online, reading entire volumes of the magazine allowed me to perceive the context in which Vignola worked and discover unmapped items, too.

When I think about it, it is amazing how much I was able to achieve in only one week at the Library this spring, thanks to the generous support of everybody there, the great assortment of historical materials on offer and, most of all, the easy access to them.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers