Daniel M. Russell's Blog, page 33

May 13, 2020

Answer: Extramusical sounds that people make during performances?

Ay yi yi yi yi!

This week's Challenge was to find any:

extramusical sounds and yells

that happen during a performance.

For examples, gritos are common in mariachi performances, you've probably heard them before.

Pedro Infante doing a grito in performance (To repeat from last time: A grito is a common Mexican interjection (typically at loud volume during a song), used as an expression of joy, sadness, or excitement. Even though it's not part of the music, it IS a part of the performance!)

Pedro Infante doing a grito in performance (To repeat from last time: A grito is a common Mexican interjection (typically at loud volume during a song), used as an expression of joy, sadness, or excitement. Even though it's not part of the music, it IS a part of the performance!) Today's Challenge isn't to find out more about gritos, but...

1. Can you find examples of other outcries / sounds / shouts that are analogous to a grito. That is, they are (in some sense) outside-of-the-music--that is, extramusical.

The real question for this week is How can you search for something like this that's so... difficult to describe?

This happens: you have an idea, but it's not really clear how to make it clear enough for a good search. Let me tell you what I did, and what strategies I used.

Strategy 1: Get an overview of what we already know about the topic (that is, the grito).

How do we do that?

The best overview mechanism I know is Wikipedia, so let's look at that.

[ grito Wikipedia ]

where we find that the grito...

This interjection is similar to the yahoo or yeehaw of the American cowboy during a hoedown, with added Ululation trills and onomatopoeia closer to "aaah" or "aaaayyyyeeee," that resemble a laugh while performing it.

The first sound is typically held as long as possible, leaving enough breath for a trailing set of trills.

From this short description, we've learned a few new terms: yahoo, yeehaw, and ululation. We also picked up that a yahoo cry often happens at hoedowns (country music performances that . That certainly qualifies as extramusical. (No jokes about Yahoo!, please...)

Strategy 2: As you do your research, be sure to pick up on any new terms (or concepts) that can lead you to more discoveries.

In the previous paragraph we learned yahoo, yeehaw, and ululation.

Let's drill down on that term, ululation. What can we learn from that?

Again, Wikipedia (ululation) is our friend telling us that:

Ululation is practiced either alone or as part of certain styles of singing, on various occasions of communal ritual events (like weddings) used to express strong emotion...

Ululation is commonly practiced in most of Africa, the Middle East, Central-to-South Asia, and in the Indian states Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Bengal, Odisha, Assam, and Sri Lanka. It is also practiced in a few places in Europe, like Cyprus, and among the diaspora community originating from these areas.

And it appears as an extramusical sound as well...

...[ululation appears in the ] music of artists performing Mizrahi styles of music... [it] is incorporated into African musical styles such as Shona music, where it is a form of audience participation, along with clapping and call-and-response.

This tells us a couple of things: an ululation is common in many different cultures (note: it's zaghrouta in Arabic--same thing), and tells us that clapping is yet another kind of extramusical sound.

And, of course, we can use this query to find out more about the use of ululation in songs:

[ ululation music song ]

This quickly leads us to Shakira's famous ululation during the Superbowl performance of her hit song "Hips Don't Lie" (2019). (Watch it here.)

Strategy 3: Keep modifying the query to explore the space near your core concept.

What if I modify that last query with a more generic term than "ululation"? Let's try this:

[ shout music song ]

... this leads to a bunch of results about the song "Shout" by the Isley Brothers. That's not helpful, so I changed the query yet again, trying to broaden it:

[ shout music ]

But that leads to "Shout Music," a kind of exuberant church music of the American south (especially in black churches). While it's loud, it's expressly musical, so it's not quite what we're looking for in this Challenge.

So I modified the query a bit a third time, providing a bit more context around the time of the shout/ululation. THIS query modification worked.

[ shout at end of musical performance ]

And THAT led to a treasure trove of different kind of shouted accolades that happen at the end of a musical performance. You know about those shouts of "Bravo" or "Encore" over the ending notes of an especially wonderful performance. But as found on the SERP, these kinds of end-of-the-concert shouts have an etiquette all their own.

In this guide, the Indianapolis opera has several suggestions about what you can yell at the end of a musical piece (I like the way they make an imperative suggestion!):

You will say “Bravo” (Brah-voh) for a single male performer.You will say “Brava” (Brah-vah) for a single female performer.You will say “Bravi” (Brah-vee) to a group of all male performers or a mix of male and female performers.

You will say “Brave” (Brah-vay) to a group of all female performers.

In fact, on occasion, audience members might also shout at the conductor before OR after the performance. You may hear “bravo!” or a “maestro!” as a token of appreciation directed at the director.

I also found a more general Wikipedia article about concert etiquette, which brings up an excellent point:

Concert etiquette has, like the music, evolved over time. Late eighteenth-century composers such as Mozart expected that people would talk, particularly at dinner, and took delight in audiences clapping at once in response to a nice musical effect. Individual movements were encored in response to audience applause....

In opera a particularly impressive aria will often be applauded, even if the music is continuing. Shouting is generally acceptable only during applause. The word shouted is often the Italian word bravo or a variation (brava in the case of a female performer, bravi for a plural number of performers, bravissimo for a truly exceptional performance). The word's original meaning is "skillful" and it has come to mean "well done". The French word encore ("again") may be shouted as a request for more, although in Italy and France itself bis ("twice") is the more usual expression. In some cultures (e.g., Britain) enthusiastic approval can also be expressed by whistling, though in others (e.g., Italy, Russia) whistling can signify disapproval and act as the equivalent of booing.

I also learned about the expression hana hou, shouted at the end of a great musical performance in Hawai'i (bascially "Good job! Encore!"). You can hear people chanting at the beginning of this video (of Bruno Mars performing in Hawai'i where the locals shout hana hou instead of encore).

What else is there? What else do people shout (or make interesting sounds) in a group setting (or musical setting)?

Strategy 4: Generalize the terms of your query to find more "nearby" concepts.

For example, if you include "people" and modify the query: [people shout during music ]

you'll discover kakegoe shouts during Japanese traditional music, when enthusiastic audience members shout out the name of an actor at particularly exciting or memorable moments. (You can find examples here--just click on the family crests and download the sound files to hear what a kakgoe sound like.)

You can keep going in this way for a long, long time. You'll discover yells during various kinds of musical traditions. Think of cries liks Laissez les bons temps rouler! in Cajun and Zydeco music, or shouts of "Hallelujah" or "Amen" in gospel performances, or even various whoops during polka band performances. It's all extramusical, and all very exciting.

Search Lessons

You can see the strategies up above, but here they are, repeated for your edification:

Strategy 1: Get an overview of what we already know about the topic (that is, the grito) and work outward from there.

Strategy 2: As you do your research, be sure to pick up on any new terms (or concepts) that can lead you to more discoveries.

Strategy 3: Keep modifying the query to explore the space near your core concept.

Strategy 4: Generalize the terms of your query to find more "nearby" concepts.

Following these strategies, as well as being willing to continuously refine your research question (and thereby become more clear about what you seek), will give you a powerful set of SearchResearch tools for investigation!

Search on!

Published on May 13, 2020 12:54

May 8, 2020

How to fly through Google Maps in 3D

"That's crazy! How did I not know that??"

That was the reaction I got from a friend when I switched into Google Maps 3D mode. If you've seen it before, it's all very straightforward and obvious, but as I learned from my friend, not everyone knows how to do this!

It's actually very easy.

To switch into 3D ("flying around") mode do this:

1. Search for your place (in the image below, I searched for the island of Bora Bora in French Polynesia):

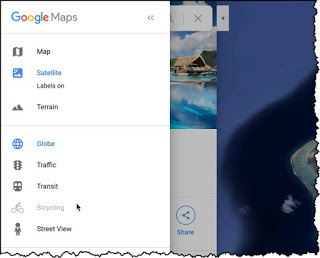

2. Switch to Satellite mode by clicking on the Satellite icon in the lower left corner of the map:

3. Click on the 3D button on the lower right corner of the satellite image. You can then zoom in/out with the + / - buttons in the lower right, or use a two-finger pinch-to-zoom gesture on a touchpad. (The scroll wheel on a trad mouse works too.)

4. To move around... that is, to change your point-of-view, you use:

Control+long-press on the mouse and

drag the mouse aroundwhile pressing the button

That's how I got to this view of Bora Bora.

Notice that I closed the left-hand panel by clicking on the leftward pointing triangle (just to the right of the search bar), and then made the labels disappear by clicking on the 3 lines in the upper left corner of the search panel (to the left of the search box). This is called the "hamburger" menu, and will look like this when you click on it:

Then you can click on the "Labels on" item, which will toggle the labels on/off. (I know this isn't obvious, but now you know how.)

I also made a short video about how to do this.

https://youtu.be/rMRAL6dvvK0

Hope you find this helpful!

Search on.

Published on May 08, 2020 10:08

May 6, 2020

SearchResearch Challenge (5/6/20): Extramusical sounds that people make during performances?

As you know, I love music...

... that's not a surprise.

What might be a surprise is that I used to NOT understand why some people would make noises while the musical performance is going on.

I don't mean babies crying (that's what babies do), or people unwrapping their lozenges in the concert hall (better that than coughing). What I've always found surprising are the:

extramusical sounds and yells

that happen during a performance.

For example, if you've ever been to a mariachi performance, you might have heard one of these "ay yi yi yi" cries ring out during the song.

Pedro Infante doing a grito in performance A grito is a common Mexican interjection (typically at loud volume during a song), used as an expression of joy, sadness, or excitement. Even though it's not part of the music, it IS a part of the performance!

Pedro Infante doing a grito in performance A grito is a common Mexican interjection (typically at loud volume during a song), used as an expression of joy, sadness, or excitement. Even though it's not part of the music, it IS a part of the performance! Once I learned this about gritos, I became much more understanding about these sounds (and non-traditional sounds in general).

Here's what a grito sounds like (skip to 00:20:00).

You can learn how to do a grito by looking at this quick tutorial on how to do it (skip to 00:26:00).

Today's Challenge isn't to find out more about gritos (they're cool and everything, but now you know about them)... the Challenge is broader than that.

1. Can you find examples of other outcries / sounds / shouts that are analogous to a grito. That is, they are (in some sense) outside-of-the-music--that is, extramusical.

I can think of a couple of examples of sounds like in other countries' traditional music (maybe you can too). The real question for this week is How can you search for something like this that's so... difficult to describe?

As always, let us know what you discover. But even more importantly, tell us HOW you found it. This is a bit tricky, so your solution process will be super interesting to us all.

Leave your answer in the comments.

Search on!

Published on May 06, 2020 11:55

May 1, 2020

Comment on... The Future Through the Past - Using archival news to see what's next in COVID

As soon as I clicked "Publish" I realized I'd forgotten to...

... add in some of the good stuff in my notes file.

IN PARTICULAR... If you recall, a big part of the point of this week's Challenge was to find similarities between COVID and the Spanish flu, and by looking at the similarities (and differences) to figure out if there was something we might extrapolate from then to now. ("The Future Through the Past," in a phrase.)

So here's a little addendum listing a few of the points of commonality I found, and a bit of what this might portend.

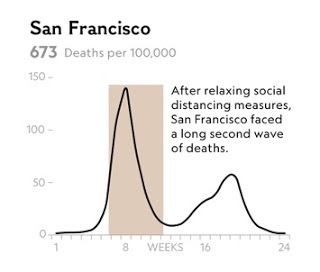

* Opening back up too soon..

In 1918 there were huge pressures to open up cities and counties that had been under the Spanish Influenza "social distancing" (stay-at-home) orders. Just as now, people protested that the lockdowns were hurting the economy and destroying livelihoods.

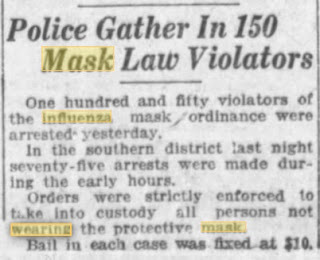

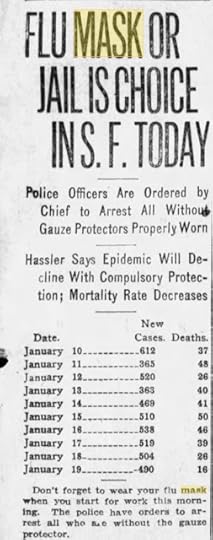

San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918

San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918And, just as the epidemiologists are predicting for states that relax on social-distancing measures too soon for COVID-19, cities in late 1918 and early 1919 had second and 3rd waves of the flu.

In a beautiful piece of work, the National Geographic published the curves for many cities in the US (collecting the data after 100 years). The bottom of the dip after the first peak is around Jan 1, 1919. You can see what relaxing the measures too soon did...

P/C National Geographic, 2020.

P/C National Geographic, 2020. * Belief in strange / magical cures...

For instance, here are a few beliefs from 1918 that could be easily matched with magical beliefs in 2020...

Does rain destroy the flu?

Some folks believed the flu could be eradicated by “atmospheric conditions.” That is, the disease could be strongly affected by rain. “...as a result, the deadly influenza germs have probably been completely eliminated in this part of the country.” Los Angeles Herald, V. XLIII, N 283, 28 September 1918

Camphor (a potent smelling oil or waxy substance) could used as a way to ward off flu.

Boys with bags of camphor around their necks as a flu repellent. (1918)

Boys with bags of camphor around their necks as a flu repellent. (1918)There was a run on camphor large enough for the chemical and pharmaceutical businesses to take note.

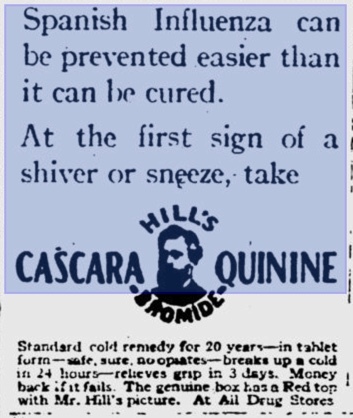

And, just as in our COVID days, there was a widespread belief that a quinine compound could be a cure for the Spanish flu:

Flu quinine pills - Lawrence Journal-World, Nov 16 1918.

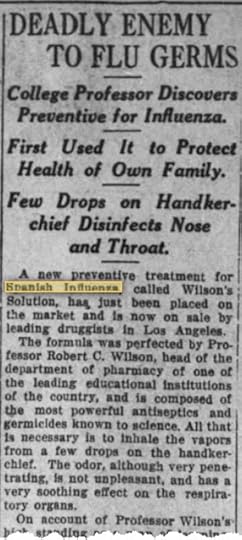

Flu quinine pills - Lawrence Journal-World, Nov 16 1918.Perhaps disinfectants and germicides will work when taken internally. In a remarkable insight, Professor Wilson seems to have discovered the value of "the most powerful antiseptics and germicides" on the Spanish flu. (It's interesting that he's described as "head of the pharmacy department of one of the leading educational institutions of the country." Why not just tell the reader the name of that institution?)

Los Angeles Times, 20 Nov 1918.

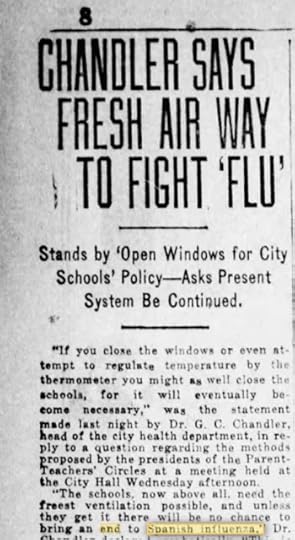

Los Angeles Times, 20 Nov 1918.Fresh air cures the Spanish flu?

The Times (of Shreveport, LA) Jan 31, 1919

The Times (of Shreveport, LA) Jan 31, 1919

* Conspiracy theories were many ...

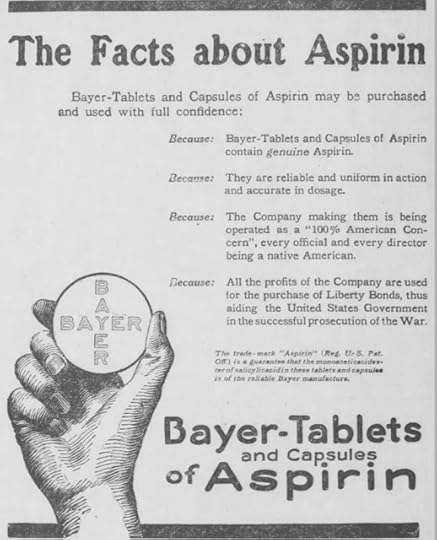

As with the purported beginnings of COVID-19 in China, there were widespread claims the Germans (the antagonists of World War 1, which was raging at the time) spread the disease and that Bayer aspirin was the carrier of Spanish influenza.

The rumor was that “...the aspirin tablets contain influenza germs and some slow poison,” according to the New York City Weekly Bulletin of the Department of Health (Oct 19, 1918) . This caused the Health Department to conduct laboratory tests of aspirin purchased randomly from locations throughout the City.

Nothing was ever found, however, but Bayer was moved to invest heavily in advertising ensuring that buyers had a favorable impression of their product. Not only was Bayer Aspirin a good product, but it's a "100% American Concern."

Not understanding the disease...

And so there were attempts to develop an early proto-vaccine (which they called a serum) that was largely based on the extracts of people who had survived the disease.

San Francisco Examiner, Oct 29, 1918

San Francisco Examiner, Oct 29, 1918Even in 1918, treating people with “grippe serum” or “plasma donation” (in 2020) is an attempt to capture antibodies in the blood of people who survived the flu. Medical technology of 1918/1919 wasn't sure what caused the flu, but they knew that transfusions of serum could help in some cases. (NYTimes article on plasma donations in 2020.)

And it was really unclear WHAT was causing the flu. Was it the bacterium Influenzae bacillus as some thought? There were contradictory answers (this is a compilation of possible causes):

Casper Star-Tribune (Apr 23, 1919)

Casper Star-Tribune (Apr 23, 1919) Some populations hit harder than others

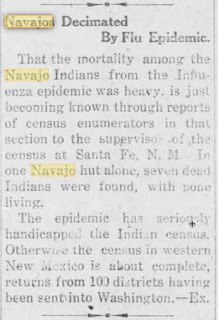

In 1918, Navajo country was hard hit with high rates of mortality (American Indian Quarterly, 2014)

The St Johns Herald (AZ) Mar 25, 1920

The St Johns Herald (AZ) Mar 25, 1920... with indigenous peoples worldwide suffering massive mortality rates. Here's one example:

Common belief: It's just an ordinary flu... nothing special...

“Worry kills more people than the disease itself,” a Chicago public health official was quoted as saying in 1918. “The so-called Spanish influenza is nothing more or less than old fashioned grippe.” Of course, you hear people saying that now about COVID as well.

New Arizona Daily Star, Jan 17, 1919

New Arizona Daily Star, Jan 17, 1919And... we were tremendously unprepared...

A report sent to the U.S. Public Health Service described conditions on the front lines of the Spanish flu, 1918.

"...[Doctors were] overwhelmed with work [and] were handicapped by inadequate transportation and two days behind in making calls; many patients . . . had been sick in bunk houses and tents for several days without nourishment, or medical and nursing attention, the sanitary conditions of the bunk houses were deplorable; the mess halls were grossly unsanitary and their operation much hampered by the lack of help; the existing hospitals were greatly overcrowded with patients; and patients were waiting in line several hours for dispensary treatment, and were greatly delayed in obtaining prescriptions at the pharmacy. The epidemic was so far progressed that the immediate isolation of all cases was impossible."

And, as we're seeing today, there was limited capacity to handle all the dead bodies, putting office spaces and theatres into service as holding places.

The News Journal, Wilmington, DE (Oct 15, 1918)

The News Journal, Wilmington, DE (Oct 15, 1918) The Dayton Herald, OH (Oct 7, 1918)

The Dayton Herald, OH (Oct 7, 1918) In the end...

The Spanish influenza came, and went, and came back multiple times until finally, by 1920, it was gone. Nobody really knows why (although there are lots of theories, mostly centered around herd immunity).

And, oddly enough, there seem to have been no grand summary articles announcing the End of the Spanish Flu. (At least I couldn't find any. If you do, please let me know!)

The articles about Spanish flu just trail off in late 1920, although research continued for a bit, including the finding that (again, echoed in our own time) that cats might carry the disease and transmit it to humans.

San Francisco Examiner (Dec 11, 1921)

San Francisco Examiner (Dec 11, 1921) I think we've made the point: Looking at an analogous past event really can help us anticipate what will happen in the future. We should have known that (as pointed out above) that people would open up from their social distancing and masking too early, and suffer more upticks in the number of cases. Or, that people would concoct crazy ideas about what caused and cured the disease. (No, neither camphor bags or internally applied germicides actually help.)

There was even one additional SearchResearch Lesson:

SearchResearch Lesson

The hardest lesson of all for me to learn was this:

1. When you find something while browsing through online archives, MAKE A COPY OF IT! I can't tell you how many amazing things I found and mentally noted--but did not bookmark or write into my notebook. This is a huge mistake. In many cases I was unable to re-find the original citation, even though I was pretty sure I accurately remembered the article.

Don't expect that your memory of the article will be sufficient to find it again. Trust me on this. You wouldn't believe some of the things I found, but then lost in the sands of the archival news repositories. Don't do that: If it's good or interesting, capture it while you're there... don't count on re-finding it!

Hope you found this follow-up note of interest. I certainly had a good time doing all of this research with you.

Keep searching!

Search on!

Published on May 01, 2020 11:29

April 29, 2020

Answer: The Future Through the Past - Using archival news to see what's next in COVID

Archival newspapers are a great resource...

... if you can find them... AND if you can understand them.

Reading through old news is incredibly illuminating, especially when you're reading about past pandemics--it doesn't get any more fascinating than this.

1. Can you find articles from the news archives of 1918 and 1919 that will show us what happened back then, and MORE IMPORTANTLY, give us a clue about what might happen in the months and years ahead?

Searching in older content requires a bit of thought. The farther back you go, the more you notice that the way people spoke and wrote in the past is a bit different than the way we do now.

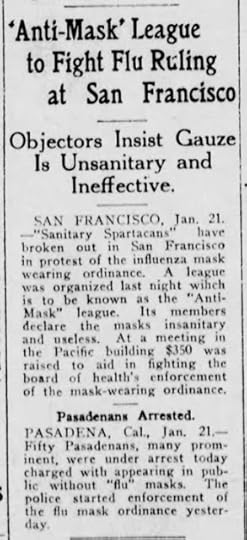

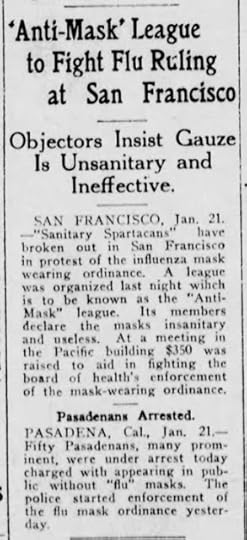

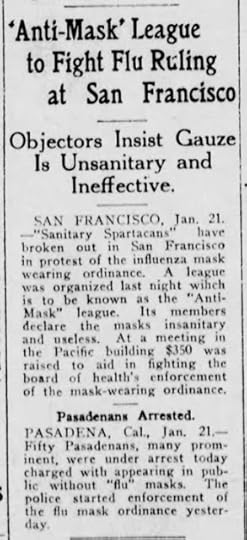

Here's an article from the LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919) about the "Sanitary Spartacans" and the "Anti-Mask League" meeting to raise money to fight the mask-wearing ordinance. I just found this while searching through a news archive, searching for "San Francisco" and "Spanish flu."

LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919)

LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919)

Orienting with a timeline:

To begin, I noticed that NPR commentator Tim Mak wrote a truly remarkable (and lengthy) blog post about the parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This is a great source of ideas, but more importantly--it points out that a timeline and current historical documents are an incredibly useful thing to have as a way to structure our search into the archives. Let's look for some other timelines:

[ timeline Spanish flu ]

Yields a lot of timelines. A really interesting timeline came from the American College of Emergency Physicians, which contains this bit about the end of the pandemic:

Obviously, San Francisco made a huge mistake in declaring the Spanish Flu to be over.

In looking at the CDC's timeline, we learn that:

It's easy to search for current historic documents with a search like:

[ history of 1918 flu ]

A search like this gives lots of articles. (Example: Washington Post, "To save lives, social distancing must continue longer than we expect: The lessons of the 1918 flu pandemic" which points out that cities such as Denver had a second wave of flu illnesses in December, 1918, rolling into January and winding down by late spring.

More to the point, for our purposes, these kinds of timelines and retrospective articles give us some dates, language, and ideas to search for in our archival newspaper search.

Finding Newspaper Archives:

Obviously, you'll need to first figure out how to access and search through news archives. (See my earlier SRS post about this: Online News Archives and another one for some tips about how to do this.) The simplest way is to search for:

[ list of newspaper archives ]

which will quickly take you to the great Wikipedia list of digitized newspapers that covers the US and many other countries.

From that list I mostly chose to use the Library of Congress Chronicling America site, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection. Both have extensive collections and cover the years 1918/1919. (For backup, of course I'd check the Google News Archive. That archive has a very different set of sources that either Chronicling America or the CDL.)

In addition, I know about and use the commercial site Newspapers.com, which has a really marvelous search interface (and their display interface is, without question, the best in the business). It costs real money, but some public libraries offer access (through their web portal), and many (nearly all?) university libraries have access to them as well. This is yet-another reason to hang onto your university/college library account for as long as they'll let you!

In all cases, you probably will want to use the the advanced search interfaces. They give you a LOT more control over what you're searching for. Here's the LOC's advanced search interface.

Note that you can select the newspapers, or all papers in a state, give a date range, and specify your search with ANY (that is, OR), with ALL of the terms, or with a phrase (that is, like a double-quoted Google search).

Finding great search terms:

As noted, the language of 1918-1919 is a little different than what we use today. The trick here will be to find the right search terms that will let you discover the major events of the pandemic, and what we should look forward to. Off the top of my head, I wasn't sure what to search for to get into this topic. It's useful just to start reading some articles and begin taking notes about terms you find.

I'm a real advocate for notetaking as you do your research, and in this case, I just created a Google doc and poured lots of thoughts, links, and ideas into it. That becomes my "notes bucket." In particular, I'm taking notes on the terms and language used at the time. (Here's my example of a notes bucket about Spanish Flu.)

This means that you'll be able to focus your research questions as you read along. Some special terms from that time are: "Anti-Mask League" "sanitarian" "Public Health Board" and so on. (See the notes for more.)

Let's look at some of the questions that I asked:

This turned out to be a rather difficult question to answer! World War 1 had been raging since 1914 and ended on November 11, 1918... which tangles up economic recovery from the war with economic recovery from all of the Spanish flu misery. (I tried various queries, but it's a real confusion of results. This is probably better answered by more recent economic analysis such as that of Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner (from the US Federal Reserve) who write that:

They go on to say that the increase in mortality from the 1918 pandemic (relative to 1917 mortality levels, which was 416 per 100,000) suggests a 23 percent fall in manufacturing employment, and a 1.5 percentage point reduction in manufacturing employment to population.

In other words, a big outbreak spelled economic disaster for affected cities. But they found that the introduction of social distancing policies is also associated with positive outcomes in terms of manufacturing employment and output. Cities with faster introductions of these social distancing and mask policies had 4 percent higher employment after the pandemic, while ones with longer durations had 6 percent higher employment after the disaster. That's a huge surprise.

In other words, social distancing measures that save lives can also, in the end, soften the economic disruption of a pandemic.

The takeaway is clear: These policies not only led to better health outcomes, they in turn led to better economic outcomes. Pandemics are very bad for the economy, and stopping them is good for the economy.

But... I couldn't find this easily in the archival news. It's only with the distance of time that these results became evident. Sometimes, you just have to wait for history to catch up.

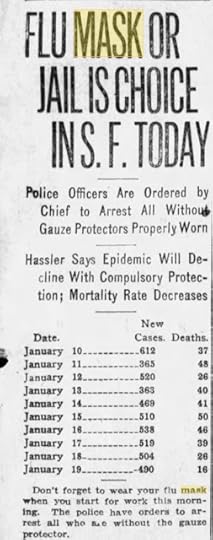

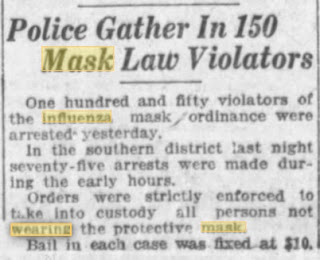

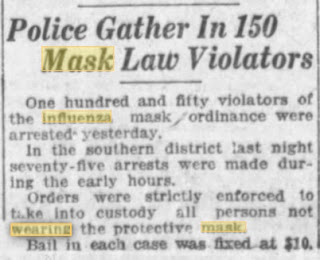

On the other hand, this was a straightforward Research Question to answer. We already found the "Anti-Mask League" which appears in multiple newspaper accounts in early 1919, as well as the proceedings of the Board of Supervisors for San Francisco, January 1919. Here, the Anti-Mask league petitions for relief from "the burdensome provisions of this measure."

Note how similar the argument is between then and now. ".. it was not in keeping with the spirit of a truly democratic people to compel people to wear the mask that do not believe in its efficacy..."

Using a special term (like "Anti-Mask") works well. But I also found good results by date-restricting my archives searches to 1918-1919 and doing searches like:

[ "Spanish influenza" mask protest ]

The bottom line here is that protests about wearing masks was fairly common. As we're seeing today, people hated wearing masks. Police enforced mask-wearing (at least in San Francisco), but it was always a tense and difficult situation, even though then, as now, it's clear that masks really do help suppress the spread of the infection.

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919

San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918

San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918

Interestingly, one of the things I picked up in this search is that not all of the news archives are equal in coverage or scope!

For this search, there were no hits in the California News repository, but over 100 in the Library of Congress collection, and over 30 in the Google News Archives. Moral here--for complete coverage, you have to check multiple sources with variations on your query to make sure you find what you seek.

Searching for orders imposing masks or limiting movement wasn't hard, but it was a bit tedious. With a search like:

[ "Spanish influenza" health board orders ]

it was easy to find when bans were imposed, but finding the removal of the orders was tricky. Often, a search like:

[ "Spanish infuenza" lifted OR removed

orders health board ]

would find the lifting of a ban that was issued by the local health board, but it was a little hit-or-miss. I could FIND them, but it was quite a bit of clicking and looking around to find a ban's imposition and then removal... and then re-imposition, and re-removal...

Here's one example:

In this case, the article tells us that it was imposed on Oct 7, and then lifted on December 18, 1918. (And yes, the mayor had to reimpose the ban in early 1919.)

Apparently, the Spanish flu just vanished. In the archival record there's a diminishing of articles over time, but no clear "The End!" articles were written.

Wikipedia helpfully tells us that "...Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out."

This is a lesson too... It's hard to look for the absence of something, or the unclear and uncertain ending of an ongoing event... Like the end of the flu.

Search Lessons

There are many here:

1. Timelines are great to orient you and give you times / topics to search for. This is good advice anytime you start doing research on a particular topic. Get a headstart by looking for something that organizes the events and times you're looking for... And mine it for key terms, names, and phrases.

2. You need to use multiple online archives. In this case I used 4 different archives (Library of Congress, California Digital News, Google News Archives, and Newspapers.com). A careful researcher will want to cross-check over multiple collections. No one resource has it all!

3. Different archives have very different search capabilities. Some don't have a good advanced search function (the ability to filter metadata such as "state of publication"), although all offer date limits. Some handle double quotes correctly, others are a bit lax in their interpretation. It's usually worth spending a little time figuring out how this particular archival search actually works.

4. Sometimes the original source material is too close to the events of the time for good archival search. Figuring out the economic effects of the pandemic isn't something that's written about a lot at the time, but can be figured out much later, when researchers can synthesize data from multiple sources over a longer period of time.

5. News archival search isn't easy or fast. Settle in and enjoy the searching because it takes time to mine the past.

6. Learn the terms of the past. As you see in the above examples, you sometimes need to pick up specialized terms that you might not use in everyday life today. (I never use the term "Health Board," although it's a very useful term when searching for medical events in the early 20th century!)

I hope this was useful... Knowing these lessons will definitely be handy when you next do an archival news search!

Search on!

... if you can find them... AND if you can understand them.

I have to admit that I spent a LOT of time on this Challenge. It was just a fascinating bit of research. The more I dug, the more I found. At this point, I could write a book! But that's not on the agenda. Instead, this post is really focused on what I did to find the information, how I did it (and then a little bit about what I found).

Reading through old news is incredibly illuminating, especially when you're reading about past pandemics--it doesn't get any more fascinating than this.

1. Can you find articles from the news archives of 1918 and 1919 that will show us what happened back then, and MORE IMPORTANTLY, give us a clue about what might happen in the months and years ahead?

Searching in older content requires a bit of thought. The farther back you go, the more you notice that the way people spoke and wrote in the past is a bit different than the way we do now.

Here's an article from the LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919) about the "Sanitary Spartacans" and the "Anti-Mask League" meeting to raise money to fight the mask-wearing ordinance. I just found this while searching through a news archive, searching for "San Francisco" and "Spanish flu."

LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919)

LA Herald (Jan 21, 1919)Orienting with a timeline:

To begin, I noticed that NPR commentator Tim Mak wrote a truly remarkable (and lengthy) blog post about the parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. This is a great source of ideas, but more importantly--it points out that a timeline and current historical documents are an incredibly useful thing to have as a way to structure our search into the archives. Let's look for some other timelines:

[ timeline Spanish flu ]

Yields a lot of timelines. A really interesting timeline came from the American College of Emergency Physicians, which contains this bit about the end of the pandemic:

Nov. 21, 1918. Sirens sound in San Francisco announcing that it is safe for everyone to remove their face masks.

Dec. 1918. 5,000 new cases of influenza are reported in San Francisco.

Jan. 1919. Schools reopen in Seattle.

March 1919. This is the first month that no influenza deaths are reported in Seattle.

Obviously, San Francisco made a huge mistake in declaring the Spanish Flu to be over.

In looking at the CDC's timeline, we learn that:

March 1918. First wave of Spanish flu in the US

Sept-Nov 1918. Second wave of flu (somewhat more lethal)

January, 1919. A third wave of influenza, subsiding by summer, primarily in Europe

January, 1919. San Francisco: 1,800 flu cases and 101 deaths are reported in first five days. Many San Antonio citizens complain that new flu cases aren’t being reported.

It's easy to search for current historic documents with a search like:

[ history of 1918 flu ]

A search like this gives lots of articles. (Example: Washington Post, "To save lives, social distancing must continue longer than we expect: The lessons of the 1918 flu pandemic" which points out that cities such as Denver had a second wave of flu illnesses in December, 1918, rolling into January and winding down by late spring.

More to the point, for our purposes, these kinds of timelines and retrospective articles give us some dates, language, and ideas to search for in our archival newspaper search.

Finding Newspaper Archives:

Obviously, you'll need to first figure out how to access and search through news archives. (See my earlier SRS post about this: Online News Archives and another one for some tips about how to do this.) The simplest way is to search for:

[ list of newspaper archives ]

which will quickly take you to the great Wikipedia list of digitized newspapers that covers the US and many other countries.

From that list I mostly chose to use the Library of Congress Chronicling America site, and the California Digital Newspaper Collection. Both have extensive collections and cover the years 1918/1919. (For backup, of course I'd check the Google News Archive. That archive has a very different set of sources that either Chronicling America or the CDL.)

In addition, I know about and use the commercial site Newspapers.com, which has a really marvelous search interface (and their display interface is, without question, the best in the business). It costs real money, but some public libraries offer access (through their web portal), and many (nearly all?) university libraries have access to them as well. This is yet-another reason to hang onto your university/college library account for as long as they'll let you!

In all cases, you probably will want to use the the advanced search interfaces. They give you a LOT more control over what you're searching for. Here's the LOC's advanced search interface.

Note that you can select the newspapers, or all papers in a state, give a date range, and specify your search with ANY (that is, OR), with ALL of the terms, or with a phrase (that is, like a double-quoted Google search).

Finding great search terms:

As noted, the language of 1918-1919 is a little different than what we use today. The trick here will be to find the right search terms that will let you discover the major events of the pandemic, and what we should look forward to. Off the top of my head, I wasn't sure what to search for to get into this topic. It's useful just to start reading some articles and begin taking notes about terms you find.

I'm a real advocate for notetaking as you do your research, and in this case, I just created a Google doc and poured lots of thoughts, links, and ideas into it. That becomes my "notes bucket." In particular, I'm taking notes on the terms and language used at the time. (Here's my example of a notes bucket about Spanish Flu.)

This means that you'll be able to focus your research questions as you read along. Some special terms from that time are: "Anti-Mask League" "sanitarian" "Public Health Board" and so on. (See the notes for more.)

Let's look at some of the questions that I asked:

a. How did your nation recover from the economic downturn caused by the Spanish Flu? What articles can you find that tell us what to look for?

This turned out to be a rather difficult question to answer! World War 1 had been raging since 1914 and ended on November 11, 1918... which tangles up economic recovery from the war with economic recovery from all of the Spanish flu misery. (I tried various queries, but it's a real confusion of results. This is probably better answered by more recent economic analysis such as that of Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck, and Emil Verner (from the US Federal Reserve) who write that:

“While non-pharmaceutical interventions [e.g. social distancing, slowing contact rates, etc.] lower economic activity, they can solve coordination problems associated with fighting disease transmission and mitigate the pandemic-related economic disruption... ”

They go on to say that the increase in mortality from the 1918 pandemic (relative to 1917 mortality levels, which was 416 per 100,000) suggests a 23 percent fall in manufacturing employment, and a 1.5 percentage point reduction in manufacturing employment to population.

In other words, a big outbreak spelled economic disaster for affected cities. But they found that the introduction of social distancing policies is also associated with positive outcomes in terms of manufacturing employment and output. Cities with faster introductions of these social distancing and mask policies had 4 percent higher employment after the pandemic, while ones with longer durations had 6 percent higher employment after the disaster. That's a huge surprise.

In other words, social distancing measures that save lives can also, in the end, soften the economic disruption of a pandemic.

The takeaway is clear: These policies not only led to better health outcomes, they in turn led to better economic outcomes. Pandemics are very bad for the economy, and stopping them is good for the economy.

But... I couldn't find this easily in the archival news. It's only with the distance of time that these results became evident. Sometimes, you just have to wait for history to catch up.

b. How well did the protests against mask measures work out? Were the protesters successful? What happened to the number of flu cases after people stopped wearing masks?

On the other hand, this was a straightforward Research Question to answer. We already found the "Anti-Mask League" which appears in multiple newspaper accounts in early 1919, as well as the proceedings of the Board of Supervisors for San Francisco, January 1919. Here, the Anti-Mask league petitions for relief from "the burdensome provisions of this measure."

Note how similar the argument is between then and now. ".. it was not in keeping with the spirit of a truly democratic people to compel people to wear the mask that do not believe in its efficacy..."

Using a special term (like "Anti-Mask") works well. But I also found good results by date-restricting my archives searches to 1918-1919 and doing searches like:

[ "Spanish influenza" mask protest ]

The bottom line here is that protests about wearing masks was fairly common. As we're seeing today, people hated wearing masks. Police enforced mask-wearing (at least in San Francisco), but it was always a tense and difficult situation, even though then, as now, it's clear that masks really do help suppress the spread of the infection.

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919 San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918

San Francisco Chronicle, Nov 2, 1918Interestingly, one of the things I picked up in this search is that not all of the news archives are equal in coverage or scope!

For this search, there were no hits in the California News repository, but over 100 in the Library of Congress collection, and over 30 in the Google News Archives. Moral here--for complete coverage, you have to check multiple sources with variations on your query to make sure you find what you seek.

c. Was the course of the Spanish Flu pretty simple, or was it (as some have predicted about COVID), fairly up-and-down for quite a while after the initial outbreak?

Searching for orders imposing masks or limiting movement wasn't hard, but it was a bit tedious. With a search like:

[ "Spanish influenza" health board orders ]

it was easy to find when bans were imposed, but finding the removal of the orders was tricky. Often, a search like:

[ "Spanish infuenza" lifted OR removed

orders health board ]

would find the lifting of a ban that was issued by the local health board, but it was a little hit-or-miss. I could FIND them, but it was quite a bit of clicking and looking around to find a ban's imposition and then removal... and then re-imposition, and re-removal...

Here's one example:

In this case, the article tells us that it was imposed on Oct 7, and then lifted on December 18, 1918. (And yes, the mayor had to reimpose the ban in early 1919.)

d. Why did the Spanish Flu finally go away? (Or did it?) Did someone develop a vaccine for it, or why did it stop being a pandemic?This was a hard one. It was like looking for a non-event. The best approach here was to search for articles that were retrospective articles. That is, there's little point in looking for the end of something when you're not sure if the end has happened yet!

Apparently, the Spanish flu just vanished. In the archival record there's a diminishing of articles over time, but no clear "The End!" articles were written.

Wikipedia helpfully tells us that "...Another theory holds that the 1918 virus mutated extremely rapidly to a less lethal strain. This is a common occurrence with influenza viruses: there is a tendency for pathogenic viruses to become less lethal with time, as the hosts of more dangerous strains tend to die out."

This is a lesson too... It's hard to look for the absence of something, or the unclear and uncertain ending of an ongoing event... Like the end of the flu.

Search Lessons

There are many here:

1. Timelines are great to orient you and give you times / topics to search for. This is good advice anytime you start doing research on a particular topic. Get a headstart by looking for something that organizes the events and times you're looking for... And mine it for key terms, names, and phrases.

2. You need to use multiple online archives. In this case I used 4 different archives (Library of Congress, California Digital News, Google News Archives, and Newspapers.com). A careful researcher will want to cross-check over multiple collections. No one resource has it all!

3. Different archives have very different search capabilities. Some don't have a good advanced search function (the ability to filter metadata such as "state of publication"), although all offer date limits. Some handle double quotes correctly, others are a bit lax in their interpretation. It's usually worth spending a little time figuring out how this particular archival search actually works.

4. Sometimes the original source material is too close to the events of the time for good archival search. Figuring out the economic effects of the pandemic isn't something that's written about a lot at the time, but can be figured out much later, when researchers can synthesize data from multiple sources over a longer period of time.

5. News archival search isn't easy or fast. Settle in and enjoy the searching because it takes time to mine the past.

6. Learn the terms of the past. As you see in the above examples, you sometimes need to pick up specialized terms that you might not use in everyday life today. (I never use the term "Health Board," although it's a very useful term when searching for medical events in the early 20th century!)

I hope this was useful... Knowing these lessons will definitely be handy when you next do an archival news search!

Search on!

Published on April 29, 2020 16:06

April 22, 2020

SearchResearch Challenge (4/22/20): The Future Through the Past - Using archival news to see what's next in COVID

The most undervalued resource on the internet...

... is probably the archive of newspapers.

Reading through old news is incredibly illuminating of our own time. You can, in many cases, see the Future Through the Past.

As someone wise said, "History does not repeat, but it does rhyme." You see that in a news headline like this one from the Long Beach Press paper of 1919.

Which looks very much like news that we're seeing today.

NPR commentator Tim Mak wrote a truly remarkable (and lengthy) blog post about the parallels between the COVID-19 pandemic and the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918.

This made me start thinking that there's an interesting SRS Challenge here. And here it is...

1. Can you find articles from the news archives of 1918 and 1919 that will show us what happened back then, and MORE IMPORTANTLY, give us a clue about what might happen in the months and years ahead?

That is, can we see the Future Through the Past?

Obviously, you'll need to first figure out how to access and search through news archives. (See my earlier SRS post about this: Online News Archives and another one for some tips about how to do this.)

The trick here will be to find the right search terms that will let you discover the major events of the pandemic, and what we should look forward to. Off the top of my head, I'm not sure what to search for to get into this topic.

This means that you'll have to clarify your research questions as you read along. For example, in the above example, the phrase "Anti-Mask League" is a promising lead. A clarifying question might be: What happened to the League?

You'll also have to figure out what questions you might like to see answered about the future course of COVID. Here are some thoughts:

a. How did your nation recover from the economic downturn caused by the Spanish Flu? What articles can you find that tell us what to look for?

b. How well did the protests against mask measures work out? Were the protesters successful? What happened to the number of flu cases after people stopped wearing masks?

c. Was the course of the Spanish Flu pretty simple, or was it (as some have predicted about COVID), fairly up-and-down for quite a while after the initial outbreak?

d. Why did the Spanish Flu finally go away? (Or did it?) Did someone develop a vaccine for it, or why did it stop being a pandemic?

I'm looking forward to our discoveries!

Be sure to say WHAT your question is (be clear about what you're searching for), then tell us HOW you found it (what online news archive did you use), and what your ANSWER/DISCOVERY is.

And, as Jon points out in the comments, I'm really interested in what you find in the news archives of your country (or state, or province, or parish).

Forward... into the past!

Search on!

Published on April 22, 2020 07:31

April 15, 2020

Answer: What are the names?

This one was pure fun...

Names (for things, people, places, songs, continents, concepts) are important!

The Challenge for this week was to identify a few names that might not be what you think!

These weren't especially difficult, but they bring up a really good point: A name might not be what you think it is. It's worth doing just a bit more digging. For instance...

1. Who is Allison Guyot? Why this is a memorable name? What does Allison Guyot look like?

The query:

[ Allison Guyot ]

quickly leads us to the Wikipedia article, telling us that Allison Guyot is a tablemount (that is, a guyot ) in the underwater Mid-Pacific Mountains of the Pacific Ocean. This particular guyot is west of Hawaii and northeast of the Marshall Islands. At the time of its formation, the atoll (from which this came) was located in the Southern Hemisphere and tectonically drifted to its current position.

It's a memorable name because it looks like someone's regular name; I could imagine meeting Allison Guyot and saying hi.

But in fact it's a submerged, truncated mountaintop that's named for E.C. Allison, an oceanographer and paleontologist at San Diego State College, California.

I couldn't find any good images of Allison Guyot, but I did find a generic image of a guyot on the Wikipedia page for guyot:

And, by checking Google Scholar, I was able to find many articles about Allison Guyot (especially about the tiny fossils found there). This article by Edward Winterer (et al.) included a great cross-section image of Allison Guyot as seen by sonar, way out in the deep waters of the Pacific Northwest.

p/c Winterer, et al. (see link below)

p/c Winterer, et al. (see link below) Winterer, Edward L., and Christopher V. Metzler. "Origin and subsidence of guyots in Mid‐Pacific Mountains." Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 89.B12 (1984): 9969-9979.

2. Who is Franklin Dixon?

Again, not hard, but I didn't know that Franklin W. Dixon is the pen name used by a variety of different authors who wrote The Hardy Boys novels for the Edward Stratemeyer Syndicate, as well as for the Ted Scott Flying Stories series published by Grosset & Dunlap.

Charles Leslie McFarlane, a Canadian author, was the originator of the series. He wrote 19 of the first 25 books in the series.

The books sell more than a million copies each year, and several new volumes are added to the list each year. The tales have been translated into more than 25 languages.

3. Who wrote the Nancy Drew mysteries?

My query was:

[ author of Nancy Drew books ]

Aha! I did not know that the Nancy Drew books were ALSO created by publisher Edward Stratemeyer as the female counterpart to the Hardy Boys series. Mildred Wirt Benson (July 10, 1905–May 28, 2002) was the original Carolyn Keene, writing 23 of the original series, beginning #1, The Secret of the Old Clock.

Like the Hardy Boy series, the Nancy Drew books are incredibly popular (translated into 45 languages). And, under the direction of Stratemeyer, the books are ghostwritten by a number of authors and published under the collective pseudonym Carolyn Keene.

So who was Stratemeyer? How did he come to be the director of such successful series?

Do the obvious search, and I learn that Edward L. Stratemeyer (October 4, 1862 – May 10, 1930) was an American publisher and writer of children's fiction.

In addition, he was one of the most prolific writers in the world, producing more than 1,300 books himself, with sales exceeding 500 million copies.

He also created well-known fictional series for young adults, including The Rover Boys, The Bobbsey Twins, Tom Swift, The Hardy Boys, and Nancy Drew series.

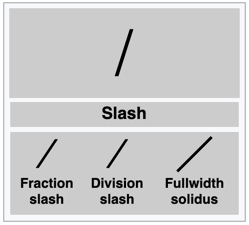

4. What is the name of this symbol? ÷ (yes, I know it’s the division symbol… what’s the REAL name of it?)

All I did was the query:

[ ÷ ]

(Yes... you can query just single characters!)

I found that it's the symbol for division, properly named the obelus.

Using this character to represent division, though common, is not universally recommended: the ISO 80000-2 standard for mathematical notation recommends only the solidus (/) or fraction bar for division, or the colon for ratios; it says that this symbol "should not be used" for division.

5. What's the name of this other symbol? Ꮬ

I included this character because it's still a surprise to some searchers that you can search for special characters. In this case, it's a letter of the Cherokee syllabary, transcribed as syllable dla.

You could also find this character by drawing it in Google Docs (as I discussed in SRS Aug 28, 2014, which showed how to draw the symbol for recognition, as well as ShapeCatcher.com, which does the same thing).

Remmij pointed out another online charater reco app at Mausr.com. These are all great. (And if one doesn't work for you, try another... or brush up on your drawing skills.)

6. How about THIS character? ⌘

Doing a search for this character leads you into a fascinating rabbithole of discovery. Most internet denizens recognize it as Apple's command key symbol, but it's also called the looped square, and is commonly used throughout Scandinavia (and a bit beyond) on road signs to indicate places of historical or cultural interest.

Somewhere in Sweden near a point of interest.

Somewhere in Sweden near a point of interest.But since it's ALSO used on Macintosh keyboards, the character has accreted a few other terms as well. If you're looking for this character in a computing (specifically an Apple/Mac context), you might want to know that some people also call this the Command key (⌘), the Apple key, clover key, open-Apple key, splat, pretzel, drone (rare), or propeller.

You can also find this called a Bowen knot.

One symbol, but 10 different terms.

6. What’s the difference between these two characters:

/ \

We already saw that the right-leaning slash (the first character) is called the solidus, commonly representing division. Let's not stop there--let's do the search:

[ / ]

Oddly, this doesn't do a search for the character if you do your search from the ADDRESS bar on the Chrome and Firefox browsers it shows a listing of your computer's file system. If you do this on Safari, it shows you what you'd expect.

IF, on the other hand, you do your Google query from the good old query box, you'll get what you expect--the results. Take note: The address bar in your browser might give very different results! (This doesn't happen often, but a few things like this crop up from time to time.)

From this search we see that this character is called a slash (the most common name), but also known as a stroke, virgule, diagonal, right-leaning stroke, oblique dash, solidus, slant, separatrix, forward slash. I also learned that there are three different kinds of the slash character, each specialized for different typesetting needs.

Fascinating.

But what about the left-leaning slash (the second character)?

Doing the same search (although with the \ character) tells us that it is sometimes called a backslash, a hack, a whack, an escape (from C/UNIX), reverse slash, slosh, downwhack, backslant, backwhack, bash, reverse slant, and reversed virgule.. and sometimes even a reversed solidus.

SearchResearch Lessons

1. Careful with certain special queries! As we see, the query [ / ] produces unexpected results IF you do it in the address bar. Another one to be careful about is "chrome"... which has all kinds of alternative completions. So... if you see something odd / interesting, try it in the other search box.

2. Check the meaning (and names) of things you think you already know. We've talked about this before, but making sure you know what something is (or what it means) AND learning other ways of describing that thing--that's a valuable habit to pick up.

I hope you enjoyed this fun/easy SearchResearch Challenge.

AND.. a special announcement: I started up a new YouTube channel. You might find Search Education to be an interesting thing to subscribe to...

Link to the Search Education YouTube channel

I've pushed a few short videos there (as advertised a couple of posts ago). If you subscribe, you'll be the first to see the videos!

Search on!

Published on April 15, 2020 09:58

April 9, 2020

Using Google Trends to find COVID data

In a recent article for the New York Times,

Seth Stephens-Davidowitz published a fascinating story (Google Searches Can Help Us Find Emerging Covid-19 Outbreaks) about using Google Trends to find coronavirus outbreaks in other countries, as well as finding unexpected side-effects of the virus.

A few people then asked me if Google knows this, why doesn't it tell us? The short answer is "you have to go looking for it." Here's why:

The article by Stephens-Davidowitz is the story about his use of Google Trends to discover what people are searching for about coronavirus. That is, he had the clever idea to use the Trends data to DISCOVER these effects in the data. The Google Trends system has all kinds of phenomena in it as revealed through the lens of what people are searching for.

As an example, look at this Trend graph for "kayaking" in the web search dataset for the United States.

That's not a surprise. Kayaking searches surge in the summertime. Makes sense. There are thousands of such observations that can be made by looking at the Google Trends data.

But in the NY Times article, Stephens-Davidowitz points out that a similarly surging query in Trends is [I can't smell] and an even more obviously surging query is [loss of smell].

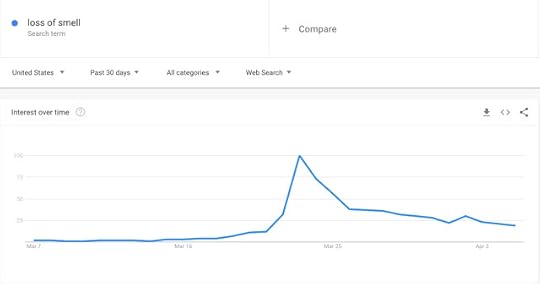

Here's the Trend graph for this query [loss of smell] (US only, past 30 days):

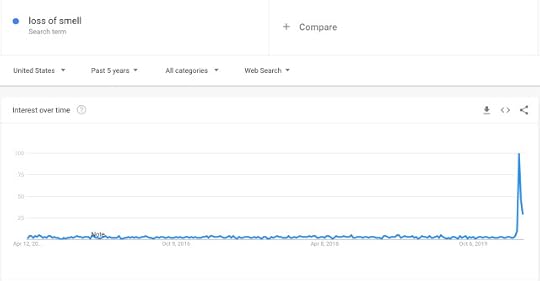

As interesting as this is, it's even more dramatic when you take into account more of the temporal context. Here's that same query trending over the past 5 years:

That uptick at the end is an amazingly large response and puts the current search query volume in context. This year is NOT like other years.

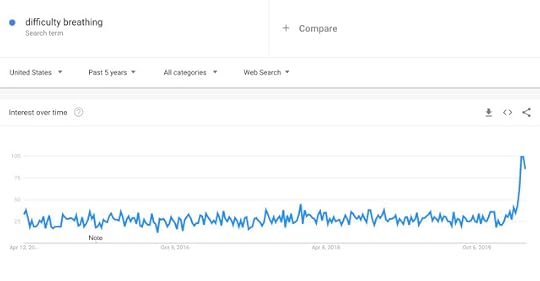

Likewise for other common COVID symptoms:

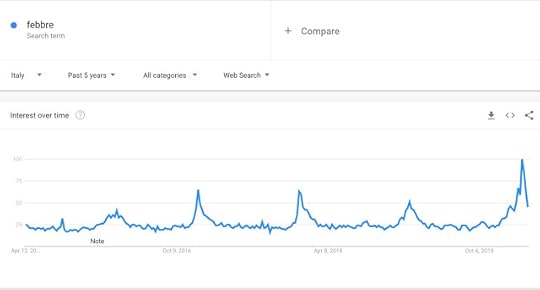

But notice this chart (below) about fever--see the annual cycle in the wintertime? That's to be expected. Yes, there's an uptick this year (far right side), but seeing the context of the previous five winters' worth of fevers makes the severity of THIS year much more apparent.

This is true in other countries/languages as well. If you ask about fevers in Italy (using the Italian word febbre), you see something similar.

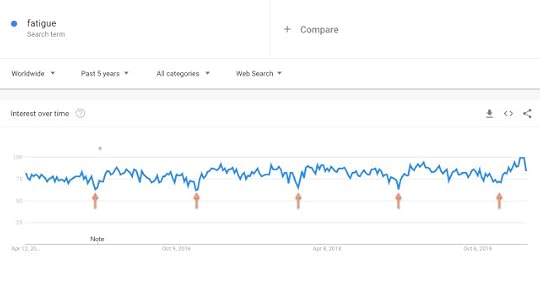

Same thing happens with another COVID symptom--fatigue. There's an annual drop in fatigue queries right at Christmas (I've marked Dec 25 of each year with arrows). It's not a huge signal, but interesting nonetheless.

Searches for [fatigue] over the past 5 years. The arrows point out the lowest volume of searches across the year, which happens to be at Christmas. I'll let you figure out why this might be true.

Searches for [fatigue] over the past 5 years. The arrows point out the lowest volume of searches across the year, which happens to be at Christmas. I'll let you figure out why this might be true. Even so, there's a distinct uptick in [fatigue] queries as well this spring, even though it's not quite as obvious as the other ones.

There's a great of information within Google Trends--but you have to go looking for it.. it won't magically raise its hand and say "here I am!"

A really interesting post to read on this topic is Coronavirus Search Trends (written by the Google Trends team) that shows the latest breakout queries at both a national and worldwide level. These are queries that have suddenly spiked in volume--a real indicator of what people are interested in finding out more about!

So while Google Trends is a great resource for researchers, you still have to go digging a little bit into the content in order to see what's happening.

Enjoy exploring with Trends. Let us know what you find!

Search on!

Published on April 09, 2020 11:50

April 8, 2020

SearchResearch Challenge (4/8/20): What are the names?

Names aren't as simple as you'd think...

As we know, having the right name for something can be very important in doing your online research. (We've talked about this before: terms, part names, geo and bio names. We'll probably talk about it in the future too.)

This week's Challenges aren't that hard, but I hope you have fun with them.

Here are some names (of people, places, and things) that might not be what you think!

1. Who is Allison Guyot? Why this is a memorable name? What does Allison Guyot look like?

2. Who is Franklin Dixon?

3. Who wrote the Nancy Drew mysteries?

4. What is the name of this symbol? ÷ (yes, I know it’s the division symbol… what’s the REAL name of it?)

5. What's the name of this other symbol? Ꮬ

6. How about THIS character? ⌘

6. What’s the difference between these two characters:

/ \

Have fun while you keep your physical distance!

And let us know how you figured it out!

Search on!

Published on April 08, 2020 12:50

April 6, 2020

A few SearchResearch short videos about finding credible medical content

As you might recall...

I put out a short video, a One-Minute Morceau (aka 1MM) on my Search Education YouTube channel this week.

Each is a short video between 1 and 5 minutes long with a brief SRS strategy or tactic for you.

I added a 3rd video today, which is why I'm collecting them here. If you want, you could always subscribe to my SearchEducation channel! (If you see the red "Subscribe" button on the video, click on it, and you'll be subscribed in a trice.

1. Finding high quality information about treatments

2. How to assess the credibility of a web site

3. Is this a credible author?

Let me know how you like them!

If I get encouraging feedback, I'll keep it up.

Search on!

Published on April 06, 2020 14:26