Daniel M. Russell's Blog, page 29

January 14, 2021

Answer: What else falls from the sky?

It's remarkable what falls from the sky...

Last week I posed these Challenges about objects falling from the sky. Were you able to figure them out? Here's what I did to answer them...

A quick Search-by-Image with the above image tells us that this was the Leonid meteor shower of 1833.

1. As you can see in the above image, meteor showers (or as in this image, a meteor storm) can be impressive. But it took the world a remarkably long time to believe that stone really fell from the sky. Can you figure out when people started to believe that rocks really fell from the sky? (Hint: There's not a singular event for this, but you should be able to figure out when the common understanding of meteors / meteorites changed.)

That's pretty straightforward, but how do you find out about some more complex question like this? ("When did people start to believe ...")

I wasn't sure how to start this out, so I tried the simplest query that I could work:

[ people believe in meteors ]

I chose this query because I figured that someone would have written something about the change in belief. Meteors are well known, and every so often one DOES fall in an inhabited area.

I was pleased to find a Smithsonian magazine article that people (in Europe at least) first saw rocks fall from the sky in L’Aigle in (Normandy, France) in 1803. At that shower, at least 3,000 identifiable stones fell. Not long before, a physicist named Ernst Chladni had published a book (1794) suggesting that meteorites came from space. He was reluctant to publish because he knew that he was “gainsaying 2,000 years of wisdom, inherited from Aristotle and confirmed by Isaac Newton, that no small bodies exist in space beyond the Moon.”

Meteorites have been known for a while (after all, even the Pharaoh Tutankhamun had a dagger made of meteoric iron), but making the connection between shooting stars and the rocks that could be found on the ground took time.

Reading the Smithsonian article made me think that another framing for this might be as story from history. So my next query was:

[ history of meteorites ]

Here I chose "meteorites" as a special term since meteorites are meteors that have made it to the ground. So I thought looking up the history of the idea would be useful. I was rewarded with the Wikipedia article on Meteorites. In there we find this section:

"...[Chladni's] booklet was "On the Origin of the Iron Masses Found by Pallas and Others Similar to it, and on Some Associated Natural Phenomena."

(Side note: We've talked about Peter Pallas before.)

"In this booklet he compiled all available data on several meteorite finds and falls concluded that they must have their origins in outer space. The scientific community of the time responded with resistance and mockery. It took nearly ten years before a general acceptance of the origin of meteorites was achieved through the work of the French scientist Jean-Baptiste Biot and the British chemist, Edward Howard. Biot's study, initiated by the French Academy of Sciences, was compelled by a fall of thousands of meteorites on 26 April 1803 from the skies of L'Aigle, France"

I found this fascinating: Chladni figured out the meteor / meteorite connection by data analysis. That work was then replicated by Biot and Howard, driven by the L'Aigle meteorite shower!

But the bottom line seems to be that European science (and the populace as a whole) didn't really accept "rocks falling from the sky" as a real thing until around 1800.

Searching for [ fish fall from sky ] leads to a whole host of web pages documenting various kinds of fish falling out of the sky. The trick here is to find sources that are credible. The Wikipedia page for Rain of animals documents many instances of animals falling from the sky, starting with Pliny the Elder reporting frogs and fish. Meanwhile, residents of Yoro, Honduras, claim that "fish rain" happens every summer--something so common it's called Lluvia de Peces.

2. As it turns out, it's not just stones that fall from the sky, but lots of other things as well. Fish are particularly common. Can you find a compelling / plausible / believable example of fish falling from the sky? (No, Sharknado doesn't count...)

The New York Times article (July 16, 2017) discusses rain of fish in Yoro, although they point out that nobody has actually seen fish fall from the sky. (It could be an upwelling of water + fish from underground sources. Other good sources include a brief from Western Texas A&M university, Australia Geographic, Science, and NPR. The most common explanation has to do with fierce dust devils or actual waterspouts (tornados over water) that pick up surface fish from a body of water and then drop them at a distance from the source. Interestingly, the fish falls seem to be fairly limited in scope (something like 300m by 30m) and always of fish that can be found in nearby lakes and streams. It's fairly easy to find mentions of fish-rains in Google Books (e.g., The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm ).

So, yes, fish can fall from the sky--not as a supernatural event, but through a little wind-assist!

3. Can you find a place where diamonds rain down from the sky? How is that even possible?

This seems implausible at best, fanciful even. But I took up the Challenge with a simple question:

[ where do diamonds rain from the sky? ]

Much to my surprise, I found a LOT of results. Here's the SERP I saw:

As with the fish-rain Challenge, the question really is how reliable are these sources? (I mean, it seems like a crazy question!)

A BBC Earth documentary video on this Challenge can be found on YouTube:

The video describes weather on Saturn and Jupiter; there are gigantic storms with massive electrical discharges--all that lightning transforms methane into huge clouds of soot (carbon), and, as that soot falls downward, the pressure and heat is so great that the carbon crystallizes into diamonds. Then, at 40,000km below the surface, it all starts to liquify.

Fascinating--but believable?

This let me take a close look at the first BBC hit reported on diamond rain on Saturn and Jupiter, but more importantly, this article gave me a link to a paper in Nature (the science journal). "Diamond drizzle forecast for Saturn and Jupiter" Maggie McKee (Oct, 2013). This in turn led to another paper by Mona Delitsky and K. H. Baines. "Diamond and other forms of elemental carbon in Saturn’s deep atmosphere." American Astronomical Society, DPS meeting #45, (Oct. 2013).

As this article points out, "At the boundaries (locations of sharp increases in density) on Jupiter and Saturn, there may be diamond rain or diamond oceans sitting as a layer. However, in Uranus and Neptune, the temperatures never reach as high as 8000 K. The cores are ~5000K, too cold for diamond to melt on these planets. Therefore, it appears that diamonds are forever on Uranus and Neptune but not on Jupiter and Saturn."

Yes, there are probably diamond-laden beaches on Uranus and Neptune, while on Jupiter and Saturn it rains diamonds, but as they fall deeper into the higher temperatures of lower layers, they liquify into carbon rain.

But how can we be sure? As one of these articles pointed out, "the chemistry is fairly well-understood, so we're confident in these predictions..." I'm not a high-temperature / high-pressure chemist, but I believe people who are.

So I believe in diamond-sand beaches, and diamonds falling as rain...

SearchResearch Lessons

There are a couple of things to note here...

1. When looking for something as abstract as a belief change, you need to look for documents that record the shift. Often this involves looking for histories of the event. If you're lucky (as we were here), you can find a small number of documents that record the first event, the first expressed belief, and the solidification of that belief. It might be a little more tricky to find slower changes, or ones that are less well documented!

2. Asking the question in a question form is becoming a really valuable technique. A question like "where do diamonds rain from the sky" isn't handled as a conjunction of terms, but is handled by a question-answering facility--this is incredibly useful for finding concepts that you might not know quite how to express! (Interestingly, I found other planets where it rains rubies and sapphires. You never know what you'll find until you look!) Notice that if you ask a silly question, Google will give you results (e.g., [ where does it rain palm trees? ]) and NOT answers to your questions. It's an important difference.

Search on!

January 6, 2021

SearchResearch Challenge (1/6/2021): What falls from the sky?

Before we get to our main topic today, let me give you a quick update on the blog.

SearchResearch began just about 11 years ago, on January 30, 2010. Since then I've written 1218 posts (just over 1 / week) and together we've written over 7000 comments!

We've had over 3.7M reads during that time--usually averaging around 20K readers / month, which puts SRS into a fairly active realm of blog sites. Thanks, Regular Readers!

Another interesting factoid: Most readers use a Windows machine to access SRS, but the two biggest browsers are Chrome and Firefox.

And, as you know, the book The Joy of Search , came out of this blog. MANY thanks to all who contributed comments and thoughts about the book (and the Challenges that went into the book).

Thus far, The Joy of Search has sold more than 5K copies, which I'm very pleased about. I won't be able to retire to Tahiti on the book proceeds, but I did buy a nice, new bike to celebrate. The whole book-writing process worked out well enough that I'm working on another book. (Which you'll hear more about later this year. Stay tuned.)

Thanks again to everyone--all of your thoughts and contributions make my life easy (and it's great fun to see all of the comments)!

On to this week's Challenges....

As I've mentioned before, I have a file of ideas about Challenges for SRS. I was just browsing through it the other day when I noticed three different ideas that would all fit together in a nice package. Can you find the answers?

1. As you can see in the above image, meteor showers (or as in this image, a meteor storm) can be impressive. But it took the world a remarkably long time to believe that stone really fell from the sky. Can you figure out when people started to believe that rocks really fell from the sky? (Hint: There's not a singular event for this, but you should be able to figure out when the common understanding of meteors / meteorites changed.)

2. As it turns out, it's not just stones that fall from the sky, but lots of other things as well. Fish are particularly common. Can you find a compelling / plausible / believable example of fish falling from the sky? (No, Sharknado doesn't count...)

3. Can you find a place where diamonds rain down from the sky? How is that even possible?

As usual, let us know HOW you found the answers!

Search on!

December 30, 2020

SearchResearch Extra: Tab to search - a handy pro shortcut

Happy end of 2020!

I'm sure 2020 will be the topic of endless PhD theses in the future, but at the moment, I'm just as happy to move on in to a brighter future.

But I wanted to leave you with a little gift--a pro tip that I use all the time, but I realized the other day that not everyone knows about! To fix this gap in world knowledge, I put together a little 1MM (1-Minute Morceaux video) for you on how to use tab-to-search. This search trick saves me a lot of time, and just might save you a few extra milliseconds.

(The key idea is that you can often use the sites' own search utility (if they have one!) to search their site in the way that THEY think is best. This isn't the same as the SITE: search you all know and love, but it uses the site's own search too.)

Link to the 1MM video: Tab to Search

Enjoy.

And search on!

December 23, 2020

SearchResearch End-of-year Summary

This is the last SRS post of 2020....

.... thank heavens!

As you know, it's been a strange year, but we've soldiered forward with 26 Challenges (and 26 Answers), a bunch of additional content (both Extras and Public Service Announcements). We had just over 1100 comments--thanks Regular Readers!

To take a look back is always rewarding--so here's my Year in SRS view.

Mysterious rainbows and fossils in the floor

Canary Islands cooking (Originally called "Where's this place?")

What is Bernard singing about?

How to find old songs (YouTube is remarkably helpful in finding old tunes. This includes REALLY old tunes, e.g., Gregorian chants.)

Does banning plastic bags actually help the environment? (It's not clear that it does.)

When to provide context? (If your research question has any depth, you need to provide some context for your answer. Big tip: Almost all questions require context.)

What research questions you’re doing? (No surprise here, most people are searching for COVID.)

Videos about finding credible medical content

(Really useful for odd names like: Alison Guyot, Franklin Dixon, or the name of the ÷ and ⌘ symbols)

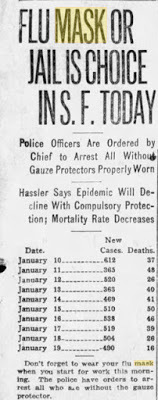

Using archival news (To see what happened in the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, and how that might be relevant to us in 2020)

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919

San Francisco Examiner, Jan 20, 1919Extramusical sounds (What are those sounds that you hear in the background of some music?)

Finding national anthems (Find the national anthems of Hawai'i and other state or national anthems that are NOT in the local language. There are more than you might think!)

Why do beans and peas move as they grow? (Because they're thigmotropic in order to find good scaffolding. Be sure to look that one up!)

Finding collections of online content (Because sometimes the best way to a source is to find the collection, and then search inside of that.)

Were there gomphotheres in Panama? (Yes, there were. And they migrated from North to South American when the Isthmus of Panama became a thing...)

Gomphotheres were native to North America. You might have had

Gomphotheres were native to North America. You might have hadone in your backyard 2.5M BCE.

Finding the latest COVID regulations (This should be simple. It's not. Here's how.)

Curious state boundaries (inclusions along state borders) (I had no idea...)

Finding a time-lapse of wildfire growth (It's not obvious how to do this.)

Everyday fact-checking: What do you do? (SRS Readers search a lot!)

Digging deeper into the story behind a photo (Contrails are complex beasts.)

The natural history of kelp forests (They're not doing well, but there are signs of hope!)

Urban development in the Indio/Coachella area (A LOT of golf courses were built.)

Who survived from the Mayflower? (Answer: Not many...)

The mystery of the polygonal areoles on autumn grape leaves (We didn't really find an answer... at least not yet. Continuing to work on this. More insights as we learn more.)

And there were a few Extras:

Double quotes / negative transfer (video) (Sometimes you do NOT want to use double quotes when searching!)

Fluff filters (Make it your reading habit to ignore fluff that's in the document. Here's how.)

How to find the Utah monolith in the SRS way (There are people with a lot of free time...)

Using Google Trends to find COVID data

Even more wildfire tracking sites (If you live in fire-prone areas, you might want to track these sites.)

Even MORE collections (Yes! Love collections.)

A few Public Service Announcements:

Started a new Search Education YouTube channel (There are six now... more are coming. Subscribe and stay in touch with the latest.)

PowerSearching course now on edX (The Advanced PowerSearching Course will be coming soon!)

Using filetype: for image searches

Fact check labels

3D flying in Google Maps (The most fun you can have while sitting at your desktop. No, really!)

Dataset search is out of beta (Hurrah!)

Three ways to find datasets

6 things to know about videoconferences (Big tip: Practice before you go live!)

Looking forward to next year?

I certainly am looking forward. The mysteries never seem to end, and since Google search is constantly changing, we'll be back here during 2021 to document the new ways you can search online. Stay tuned!

And leave a comment on which Challenges you liked (and which you didn't care for). That will be useful information as we push forward into the information forest.

Search on!

December 16, 2020

Answer: The mystery of the grape leaf polygonally changing color

Fascinating...

AS YOU RECALL..

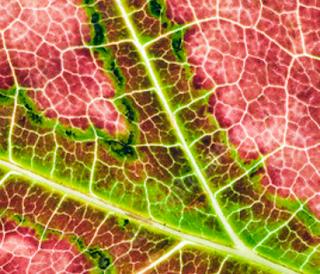

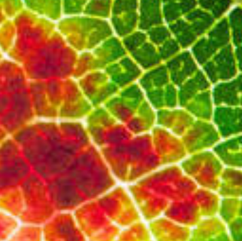

I was emailing with my artist friend Lynne Garell who captured a set of photos that are striking. I've never seen any leaves change color quite like this:

A grape leaf closeup. P/C Lynne Garell, from her series of grape leaf images.

A grape leaf closeup. P/C Lynne Garell, from her series of grape leaf images. How does this happen? How can a polygonal piece of a leaf all change at once? Is this the way all leaves change? What's going on here?

Another image from her series:

What's going on here isn't at all obvious...

Here are the Challenges I set out last week.

To begin with, I really had no ideas, but I realized that I needed some basic terminology. So I dealt with Challenge 2 first...

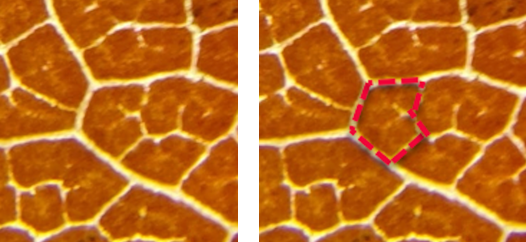

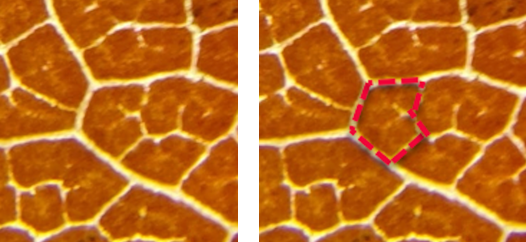

2. To answer this question for myself, I thought I'd first find out what each of those polygonal sections is called, and then search on that term. But I couldn't find it! So, a Challenge for you: What is that part of the leaf called? Here's an image that I made to illustrate the question:

That thing... what's it called? These polygons, like the ones above in Lynne's photo, would seem to be fairly obvious structural features of a leaf. But I can't figure out what they're called. Can you? (I realize that up close this looks like a giraffe's skin, but I assure you, this is a closeup of a leaf.)

I started with an easy search:

[ leaf veins ]

and just read around the results for a bit. The first hit is to a comprehensive (and fascinating) summary of what leaf veins are and how they're organized. (Leaf venation: structure, function, development, evolution, ecology and applications in the past, present and future. Sack, L., & Scoffoni, C. (2013). New Phytologist, 198(4), 983-1000.

Really interesting, but while I learned a lot about venation structures (first-order, second-order, arrangement of xylem and phloem conduits within veins!), I did not learn what the spaces in-between the veins are called.

But I DID learn that grapes are dicots, which have a reticulate venation pattern (that is, it's a web-like structure between the veins), and that "veins transport water throughout the lamina mesophyll."

That is, the leaf (as a whole) is the lamina, while the veins are made up of xylem and phloem cells surrounded by bundles of sheath cells. The vein xylem transports water from the base of the leaf throughout the lamina mesophyll, and the phloem transports sugars out of the leaf to the rest of the plant. Right? Water comes in through the xylem; nutrients go out via the phloem.

Generically, the stuff in the middle is the mesophyll, but that's too generic a term. What's a more specific term for those polygonal structures we see?

I went back to the SERP and found the Wikipedia article on Leaf, wherein I found this:

"The areas or islands of mesophyll lying between the higher order veins, are called areoles. Some of the smallest veins (veinlets) may have their endings in the areoles, a process known as areolation..."

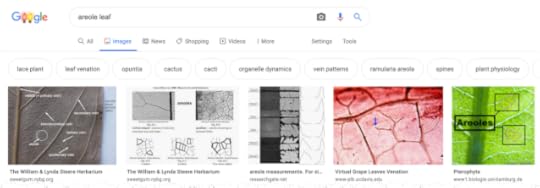

Now we've got a specific term: areole. Let's use that in our search:

[ leaf areole ]

Which gives the satisfying image search result of:

That image on the far right is from a text about fern leaf architecture, and is basically the same drawing I did above!

On to the next Challenge!

1. What is this effect called? (That is, the polygons changing color independently of the surrounding leaf to create this kind of pattern.)

This has turned out to be pretty hard.

I spent a long time trying various queries, looking at lots of image results of grape leaves... and finding results like this, nice, but not polygonal:

What's more, I was NOT able to find grape leaves that change color areole-by-areole. As you can see from the images above, generally speaking, grapes change color on a fine-grain size, not by the entire areole changing color at once. Even the top image in the above set isn't quantized--if you look carefully, you'll see that the areoles change color across a gradient--an entire areole doesn't change all at once.

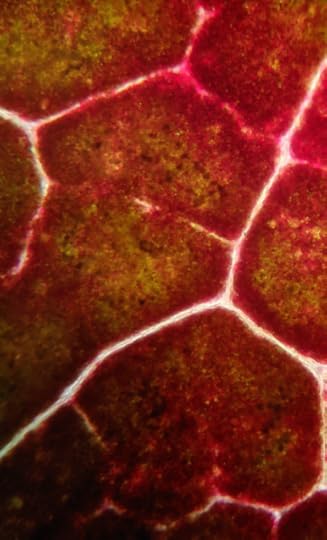

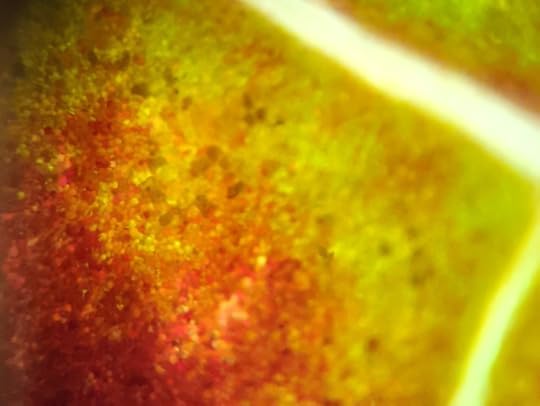

I was so surprised by this that I went out and picked up a few grape leaves from the neighborhood (with permission!) for a closer look. Here are a few of those images at increasing magnification:

In the bottom image you can see the individual cells in the mesophyll (technically, the palisade cells). The bright out-of-focus lines are the veins.

And, as you can see, not all of the cells in the areole are of the same color--there's a gradient across the areole from brown (on the far left), through red, to green just before the cells hit the vein.

So the big Challenge boils down to this: Why do these areoles all change color simultaneously?

I have to admit that I struck out on this, despite searching extensively on Scholar, News, and Images. These polygonal red patches are fairly rare!

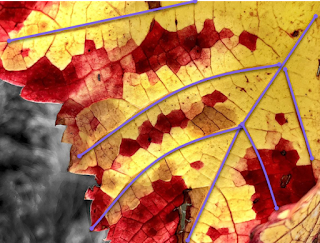

Part of the clue might be in the structure of the color changes in Garell's photos. Here I've annotated a couple of her leaves with purple lines to show that the areoles that change color are the ones farthest from the primary veins.

What causes leaves to change color in the first place? As you know, in the fall, because of changes in the length of daylight and changes in temperature, the leaves stop their food-making process. The chlorophyll breaks down, the green color disappears, and the yellow to orange colors become visible. The amount and kind of color depends on the carotenes and xanthophyll pigments in the leaf, along with development of red anthocyanin pigments.

So, in Garell's leaves, the areoles that are most distant from the veins are the ones that change color first.

While I wasn't able to find a documented explanation for the polygonal areole color changes, I'd be willing to bet that these particular grape leaves had some kind of environmental or biological stress (e.g., a bacterial infection) that let the areoles that are least connected to the main veins lose their chlorophyll first. Whatever the stressor was, it affected the entire areole, rather than just a part. Was it a hard freeze during a cold snap? Or what it something else?

At this point, we don't know the deep reasons, but just have a suggestion that these particularly lovely images capture a fairly rare color event in the French fall. Most grape leaves in France don't seem to have these beautiful polygons, but look a bit more generic. Here's a photo from near Lyon--nice, but no polygons.

Many thanks to Lynne Garell for letting me use (and annotate) some of beautiful images. If you liked these images, please check out Lynne's Etsy site for her photography. It's all beautiful.

SearchResearch Lessons

Well... there are at least two here, perhaps more...

1. You won't always succeed. I'm pretty sure there's an answer out there, somewhere, but I wasn't able to find it this week, despite multiple hours on the task. It was fun, but I didn't find an answer. But I WILL keep my eyes open!

2. Finding a specific term (e.g., areole) can help target your search much better. And yes, I'll eat my words if someone manages to find the answer to this Challenge and doesn't use areole somewhere in their search process.

I'll keep looking and will give an update if I learn more about the geometry of color-changing French grape leaves.

Laissez les bons temps rouler!

(I realize this is Cajun French, but it seems appropriate...)

Search on!

December 9, 2020

SearchResearch Challenge (12/9/20): The mystery of the grape leaf polygonally changing color

A question I get asked a lot is...

... "Where do you get your SearchResearch Challenge ideas?"

As you know, our topics vary quite a bit. One week it might be identifying a wreck that I spotted somewhere off the California coast, while another week we might be discussing the location of a mysterious statue in London, or small animals cutting a clearing around bushes in the Santa Cruz mountains. We get around.

But the Challenges I like the most are those that come from friends who ask questions that seem simple or obvious, but which, upon closer examination, reveal hidden depths.

I was email-chatting with my artist friend Lynne Garell who is living in France, loving life there, and taking wonderful photographs of the place world around her.

We started an email conversation about one of her photos that caught my eye. I've seen lots of leaves change colors over the years, but never quite like this:

A grape leaf closeup. P/C Lynne Garell, from her series of grape leaf images.

A grape leaf closeup. P/C Lynne Garell, from her series of grape leaf images. This appeared in her blog, Lo Vedo Life, the other day and it seemed impossible. How does this happen? How can a polygonal piece of a leaf all change at once? Is this the way all leaves change? What's going on here?

Another image from her series:

The more I looked into this, the more I realized that this isn't at all obvious...

So I'm translating our conversation into an SRS Challenge for everyone. Caution: I have not yet figured this one out, so it might be REALLY HARD or even impossible. But that's the fun of the Challenge, is it not? We'll set a high bar, and see if we can leap over it.

1. What is this effect called? (That is, the polygons changing color independently of the surrounding leaf to create this kind of pattern.)

2. To answer this question for myself, I thought I'd first find out what each of those polygonal sections is called, and then search on that term. But I couldn't find it! So, a Challenge for you: What is that part of the leaf called? Here's an image that I made to illustrate the question:

That thing... what's it called? These polygons, like the ones above in Lynne's photo, would seem to be fairly obvious structural features of a leaf. But I can't figure out what they're called. Can you? (I realize that up close this looks like a giraffe's skin, but I assure you, this is a closeup of a leaf.)

As always, I'm interested in HOW you found the answer! Let us know in the comments section.

Botanically yours...

Search on!

December 3, 2020

Answer: Who made it to the first Thanksgiving?

The Mayflower story is encrusted with legend and the legacy of centuries of story-telling...

Image by Sabrina Ripke from Pixabay

Image by Sabrina Ripke from PixabayAs noted, 2020 is the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower sailing to North America, and the 399th anniversary of the First Thanksgiving associated with the Mayflower Pilgrims.

They landed in Massachusetts in mid-November and barely made it through the hard first winter, which led to the Thanksgiving feast of 1621.

I wondered who was left to celebrate after that difficult year. And that leads to our Challenge today. How many souls were still around?

1. The Mayflower left England with 109 102 souls, of which only 2 perished on the way. By the time of the Thanksgiving feast in November of 1621, how many of the original settlers were still alive? How do you know?

Looking up the Mayflower story is fairly straightforward, but getting the details right is a little tricky. The queries are easy [ Mayflower voyage ] or [ Mayflower landing ] to find many different tellings of their tale.

Wikipedia: "After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, the Mayflower, with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, reached America, dropping anchor near the tip of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on November 21 [O.S. November 11], 1620." (Sorry about the typo in the number of passengers: it was never 109.)

The journey from Europe to North America was complicated. They initially planned on sailing with another vessel, the Speedwell in July, but they set out to sea, and returned for repairs twice before they Speedwell decided to stay in England, letting the Mayflower proceed on a solo voyage. A few of the Speedwell passengers transferred onto the already crowded Mayflower.

So the traditional account of the Mayflower journey begins on September 6, 1620, the day they sailed from Plymouth, but it’s worth noting that by that time the Pilgrims had already been living aboard ships for nearly a month and a half.

It was a difficult journey: 100 foot swells, everyone wet and freezing cold for much of the time.

Remarkably, only one passenger, William Butten, a servant of Deacon Samuel Fuller, died at sea, and one child was born. One of the passengers was swept overboard, but was saved by grabbing a rope that hauled him back on board. About the same time Oceanus Hopkins was born onboard. One lost, one gained.

By the time they reached Massachusetts in November and established Plymouth (the name of their settlement), it was well into the cold part of the year. With inadequate provisions and not nearly enough shelter, people started to die off. How many made it through the first year?

I tried two different queries, both of which gave me a number of resources:

[ how many Pilgrims survived first Thanksgiving ]

[ Plymouth colonists survive first thanksgiving ]

Scholastic: tells us that out of 102 passengers, 51 survived the first winter, only four of the married women (Elizabeth Hopkins, Eleanor Billington, Susanna White Winslow, and Mary Brewster). These four women, along with the older girls, oversaw food preparation for the three-day harvest feast for the colonists, Massasoit, and his 90 Indian men — the feast that we now call "The First Thanksgiving." (52 English were at that feast as the baby boy Peregrine was born after their arrival.)

By contrast, USHistory.org tells us that 44 passengers survived.

Meanwhile, a History.com article tells us that 50 passengers survived.

And PilgrimHall.org says that 53 people people made it to the first Thanksgiving. (I tend to believe this number... why? See below.)

That's a fair range of answers: 51, 44, 50, 53. If you keep digging, you'll find even more numbers!

Bottom line: there's a bit of variation in the possible answers that you'll find with an uncritical search. How do we get to the ground truth?

I noticed, as I read, that several of the articles pointed to William Bradford's book that's an account of those days, Of Plimoth Plantation (1622). Since he was on the Mayflower, and a central figure in the story, I think his report is probably the most accurate. This is an easy search on Books.Google.com (Note: A somewhat easier version to read is Bradford's History of Plymouth Plantation, 1606-1646. It's edited for clarity and fixes a bunch of errata. And you can download the entire PDF!)

So, I downloaded the PDF and found this...

Scan of original manuscript by William Bradford

Scan of original manuscript by William Bradford (Frontispiece in Bradford's History...)

Reading carefully, one finds that...

2. If you know THAT number, what were their names?!?

... on Page 407, you find the following item:

Page 407 of Bradford's History of Plymouth Plantation

Page 407 of Bradford's History of Plymouth PlantationIt's a lot of people. But when you get a few pages farther into the text, you start to read this:

Page 409 of Bradford

Page 409 of BradfordAnd if you read carefully, you can start with the initial list of Mayflower passengers, and then strike-out the ones who died before the first Thanksgiving, you'll be left with 53 Mayflower people who attended that festival day.

Of course, the simplest way I found to get to the original list of passengers was to search for it:

[ list of Mayflower passengers ]

leads quickly to a Wikipedia list of the 102 passengers onboard. (Alas, it does NOT list all of the crew. The officers are listed, but the common seamen are just in a lump. Just as with the passengers, there's also a lot of disagreement about how many sailors there were.) This list has an asterisk next to all those that died over the winter.

Going back to that PilgrimHall article, one of the reasons I found it believable when I first read it was that it actually listed all of the (known) Mayflower survivors at the first Thanksgiving. To wit,

4 MARRIED WOMEN: Eleanor Billington, Mary Brewster, Elizabeth Hopkins, Susanna White Winslow.

5 ADOLESCENT GIRLS: Mary Chilton (14), Constance Hopkins (13 or 14), Priscilla Mullins (19), Elizabeth Tilley (14 or 15) and Dorothy, the Carver's unnamed maidservant, perhaps 18 or 19.

9 ADOLESCENT BOYS: Francis & John Billington, John Cooke, John Crackston, Samuel Fuller, Giles Hopkins, William Latham, Joseph Rogers, Henry Samson.

13 YOUNG CHILDREN: Bartholomew, Mary Allerton, Remember Allerton, Love Brewster, Wrestling Brewster, Humility Cooper, Samuel Eaton, Damaris Hopkins, Oceanus Hopkins, Desire Minter, Richard More, Resolved White, Peregrine White.

22 MEN: John Alden, Isaac Allerton, John Billington, William Bradford, William Brewster, Peter Brown, Francis Cooke, Edward Doty, Francis Eaton, [first name unknown] Ely, Samuel Fuller, Richard Gardiner, John Goodman, Stephen Hopkins, John Howland, Edward Lester, George Soule, Myles Standish, William Trevor, Richard Warren, Edward Winslow, Gilbert Winslow.

The good news is that this list aligns with what you can read in Bradford's account. So I'm pretty sure that there were 53 Mayflower survivors at the first Thanksgiving.

Very little beats the original account.

3. Purely for fun extra credit, I found that THIS famous image is somehow connected with the Mayflower. Can you discover how?

Doing a Search-By-Image you'll quickly find that this dramatic image was made by Harold Edgerton, the famous high-speed-photography wizard at MIT.

Searching for the connection between Edgerton and the Mayflower is as simple as:

[ Harold Edgerton Mayflower ]

and then sifting through the results for a credible source. I found a geneology site, Geni.com that tells us: "... Edgerton was born in Fremont, Nebraska on April 6, 1903, the son of Mary Nettie Coe and Frank Eugene Edgerton, a direct descendant of Richard Edgerton, one of the founders of Norwich, Connecticut and a descendent of Governor William Bradford (1590–1657) of the Plymouth Colony and a passenger on the Mayflower."

Just to double check, I looked up Richard Edgerton, verifying the Norwich, CT connection. And then I pretty much recapitulated what Regular Reader Arthur Weiss did. To quote his outstanding comment on this:

He [Edgerton] was from Bradford's great granddaughter Alice who married Samuel Edgerton, Richard Edgerton's son.

She's listed in Bradford's descendants on page 24 on Our New England ancestors and their descendants, 1620-1900 [microform] : historical, genealogical, biographical

Governor William Bradford's eldest son from his 2nd wife was a Major William Bradford. His sixth daughter was Hannah who married Joshua Ripley. Their eldest child was Alice - who married Samuel Edgerton who is an ancestor of Harold Edgerton and the son of Richard Edgerton. (Hannah seems interesting in her own right - she acted as the settlement doctor).

To Arthur's eternal credit, he then went and edited the Wikipedia article to fix the internet. Kudos to Arthur!

SearchResearch Lessons

Several useful lessons here:

1. There is often lots of reading to extract the info you want. I ended up reading about 20 documents, noticing the variant numbers, which drove me to dig even deeper into the material. But there's just no escaping it: Sometimes you have to read extensively.

2. Don't believe the first number you find. As we saw, the numbers vary all over the place. You have to look hard to find an accurate accounting.

3. Don't necessarily trust the number you see in a search-engine answer box. Especially when the number has to be derived from a careful analysis.

Here, for instance, is Google's Answer:

It's right, as far as it goes, but kind of off target. I asked "how many people," not just men.

Meanwhile, Bing does a better job:

Bing

4. For historical information like this, when you see ambiguity, look for original content (such as Bradford's book). Note that Bradford's book also has errors--first accounts frequently do. But by doing primary document research, you're well on your way to becoming an excellent SearchResearcher (or a historian)!

Search on!

November 30, 2020

SRS Special: How to find that mysterious Utah monolith using SRS methods

I hadn't expected a mysterious monolith in the Utah desert, let alone one that reminded me of the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey...

P/C Utah Dept. Public Safety video frame

P/C Utah Dept. Public Safety video frame

... but then again, the Utah Department of Public Safety helicopter crew didn't expect to see it in a small canyon deep in the Utah redrock desert. (Watch the video at the start of the KSL TV report. The helicopter crew's cell phone video gives a good sense of how big it is and the canyon setting.)

P/C Wikimedia. Photographer: Patrick A. Mackie

P/C Wikimedia. Photographer: Patrick A. Mackie

Of course, like all good modern mysteries, the collective intelligence of the internet jumped onboard and quickly figured out exactly where the monolith was located.

In this case, the sleuthing was done by a Redditor who wrote in his post exactly how he found it. Quoting from his post:

I looked at rock type (Sandstone), color (red and white - no black streaks like found on higher cliffs in Utah), shape (more rounded indicating a more exposed area and erosion), the texture of the canyon floor (flat rock vs sloped indicating higher up in a watershed with infrequent water), and the larger cliff/mesa in the upper background of one of the photos. I took all that and lined it up with the flight time and flight path of the helicopter - earlier in the morning taking off from Monticello, UT and flying almost directly north before going off radar (usually indicating it dropped below radar scan altitude. From there, I know I am looking for a south/east facing canyon with rounded red/white rock, most likely close to the base of a larger cliff/mesa, most likely closer to the top of a watershed, and with a suitable flat area for an AS350 helicopter to land. Took about 30 minutes of random checks around the Green River/Colorado River junction before finding similar terrain. From there it took another 15 minutes to find the exact canyon. Yes... I'm a freak.

Let's dissect this a bit and think about what the Redditor did in SRS terms.

1. They pulled information from the original news story and then found details that would help zero in on the location.

Example: The helicopter crew was from the Utah Department of Public Safety. But what kind of helicopter were they flying? It's clear from the video there were at least 3 passengers aboard, but how big was the copter? As the Redditor says, they needed a "suitable flat area to land an AS350."

How do you get to that information? A query like:

[ Utah State Department of Public Safety helicopters]

gets you to their Mission Statement, which includes a list of all the aircraft flown by Aero Bureau. Turns out they only have AS350 Eurocopters, which are 10.93 m (35 ft 10 in) long. That's not a tiny helicopter, so they'd need a flat circular area at least 20 m (60 feet) in diameter to land.

2. They used publicly available information to determine the flight path. As SRSers know, it's pretty easy to find flight path information from any of a number of GPS flight information services (e.g., FlightAware and Flightradar24).

3. They inferred clues from the flight information. Noticing that the helio went off radar by dropping below radar altitude is a big hint. That dramatically reduces the amount of area you have to visually search.

4. They just looked around! As we saw in the "Find this coastline" SRS Challenge, sometimes it's useful just to get into Google Maps or Google Earth and start looking. From looking at the video, the searcher knew they were looking for "... a south/east facing canyon with rounded red/white rock, most likely close to the base of a larger cliff/mesa.." We learned from our earlier Challenge that if you've limited the search to a reasonable area, a quick visual scan can be effective.

P/C Google Earth.

P/C Google Earth.

As you can see at the tip of the yellow arrow, the Redditor got lucky in that the sun angle just happened to be perfect for casting a long, easily visible shadow. If this were shot at high noon, not much shadow would be seen.

Big SRS Lesson: The subReddit GeoGuesser is a valuable resource to know. A bit of background: People continuously post links to their GeoGuesser Challenges "where is THIS?" questions. Then other GeoGuesser Redditors jump in with ideas and comments as they play. You can learn a good deal about photo interpretation this way, as well as what kinds of clues one can use when searching for an unknown location somewhere on our planet.

There are other subReddits worth knowing (WhatBugIsThis, WhatsThisPlant, or WhatsThisThing). YMMV, but these are often great places to learn search skills in these specific domains.

Then, just as mysteriously as it appeared, the monolith was removed over Thanksgiving weekend. The various Utah and Federal government agencies deny having anything to do with it, so we're left with more mysteries.

Next Challenges for interested folks... Who made and installed the monolith? Then, who removed it? Where did it go? Will it reappear somewhere else on Earth?

I'm not going to spend any time on these mysteries, but if you happen to find out anything, let us know!

Search on!

P.S. If you need a reminder, here's the link to the YouTube clip from 2001 where the proto-humans encounter the mysterious black monolith.

November 25, 2020

SearchResearch Challenge (11/25/20): Who made it to the first Thanksgiving?

Even during COVID-19,

Image by Sabrina Ripke from Pixabay

Image by Sabrina Ripke from Pixabay

... Americans are celebrating the Thanksgiving holiday (a festival that we've discussed before in SRS, to wit, we asked Original Cranberry Recipe? and What and Why are Thanksgiving Traditions?)

And, as I was thinking about the strange and socially-distanced Thanksgiving holiday for 2020, I was struck that this year, 2020, is the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower sailing to North America, and the 399th anniversary of the First Thanksgiving associated with the Mayflower Pilgrims. (There is much debate about whether this was truly the FIRST Thanksgiving, or if the festival was celebrated earlier, in 1619, at Berkeley Hundred, Virginia, by settlers who arrived a board the ship Margaret).

The thing that struck me as I read was how different the actual story is from the one I learned growing up. As a lad I learned a happy story, one of a search for freedom and congenial relationships with the local Native Americans. But the reality is much more complicated than that.

First, there were originally 2 ships that set sail from England, the Mayflower and the Speedwell. Alas, the Speedwell was unlucky and sprang two different leaks, causing the ships to return to port twice. Then they moved 20 passengers from the Speedwell onto the Mayflower and finally left England with 130 souls on board, leaving the coast on September 16, 1620--which is a little late to be sailing to North American. The Atlantic at that time of year is cold, with high seas, and deadly dangerous. The winds blow the wrong way in late fall so it took them 66 days to reach the coast at Cape Cod, most of that time was wet, cold, and miserable in the high seas and wind. You can imagine the seasickness and overall sense of awfulness. To make things worse, they were aiming for Virginia, not Massachusetts. Whatever.

Of course, landing in Massachusetts in mid-November is a terrible idea, and no time to start a colony, and they barely survived the cold, deadly winter.

But having made it through the terrible first winter, and then the summer, it was time for a celebration, which led to the Thanksgiving feast of 1621.

Given how hard it was to survive the ocean trip, I wondered who was left to celebrate. And that leads to our Challenge today.

1. The Mayflower left England with 109 souls, of which only 2 perished on the way. By the time of the Thanksgiving feast in November of 1621, how many of the original settlers were still alive? How do you know?

2. If you know THAT number, what were their names?!?

3. Purely for fun extra credit, I found that THIS famous image is somehow connected with the Mayflower. Can you discover how?

As always, while I'm interested in your answers, I MORE interested in how you found the answers. Be sure to let us know what you did to find the answers to the Challenges, and what sources you used.

Search on!

November 18, 2020

Answer: What happened here over the past 40 years?

Date shakes.... yum.....

Shields Date Farm--with excellent date milkshakes and fascinating educational videos.

Shields Date Farm--with excellent date milkshakes and fascinating educational videos.

I haven't been to Indio in probably 20 years, so I was fairly surprised when I happened to look at the Coachella Valley on Google Maps last week. It's a MUCH different place than I remember from the days when we drove through in search of date-based frozen confections.

It's useful to know this: the center of US date production is near Indio, in the Coachella Valley. That, plus ice cream, means date shakes.

All of these changes leads us to this week's Challenge:

What are the largest changes to landuse in the Coachella Valley over the past 40 years? (That is, the valley centered around: 33.711896, -116.210818) What kinds of changes can you spot?

There are many ways to do this piece of SearchResearch, but a GREAT way start such investigations is by getting a visual overview. Google Maps works well to get a look at the place from the maps overview.

Even at this range, you can get a big clue from all of the green blocks...

That's a lot of golf courses! It's even more interesting in satellite view:

Aside from all of the green here, there's also a LOT of water in this view.

Of course, Google Earth has archival images (we've discussed this before). Here's a pic from 2002 of the Indio area. Contrast this with the image above from 2020.

But wait--isn't this a desert? Look at the color of all the ground all around the valley! Note how far away Death Valley is (not far).

So, sure, the valley is pretty clearly well-watered, but surrounded by desert. (And yes, I know that looks like a giant lake in the bottom right corner--but that's the Salton Sea. It's pretty salty--about 60 parts per thousand. By comparison the ocean is about 35 PPT. What's worse--the salinity of the Sea increases every year since it doesn't have an outflow, but just slowly evaporates.

From a land-use perspective, how is it possible to support all of those golf courses and lakes in the desert?

While that's an interesting land-use question, how can we quickly get an overview of 40 years of land uses? That's a lot of time to cover. What about a timelapse satellite view?

My query:

[ time lapse Earth ]

leads quickly to Google Earth Timelapse. It doesn't take long to search for Indio and the Coachella Valley. Here's the YouTube video I made that neatly shows the enormous changes in the valley between 1984 and 2018.

When you watch the video, look at one spot and watch how it changes over time. Mostly, you'll see the transformation of the valley floor from agricultural to golf courses, hotels, and urban areas.

While this gives a great visual summary of the changes and how profound they are, a fairly straightforward query leads to fairly extensive documentation of the changes. My query:

[ land use change Indio California ]

led to lots of news reports about various land use proposals, maps, studies, and plans. (Example: Indio land use maps, plans, and studies and articles like Land Subsidence in the Coachella Valley that covers land changes in the area over the past 100 years). In reading through these documents, it's clear that water use is one of the leading factors in growth and land use. A second query:

[ water use history Coachella Valley ]

gives somewhat broader results. (Example: the Coachella Valley Water District's history since 1918.)

Why are the results broader? Because land use is typically not a city-by-city concern, but more a regional (or county) concern. In the Coachella Valley's case, changes in water supply in the 1960s allowed the rapid growth of building, leading to Indio and the surrounding area to become a tourism destination. Golfing lead the way when, "in the 1980s, 34 courses opened. That’s about one every 100 days for an entire decade, and we had homes being built around these courses.” Palm Springs Golf: A History of Coachella Valley Legends & Fairways (2015).

So, what about land use?

The bottom line for Indio (and the Coachella Valley) is that it was an old agricultural spot that lasted for many years until a sudden influx of water supply (from the Colorado River) suddenly made growing golf courses, water hazards, and homes a much more lucrative business than dates and table grapes.

Luckily, the general land use plan has reserved significant land for agricultural purposes. But water management issues dominate the place. Land subsidence, resulting from aquifer-system compaction and groundwater-level declines, has been a concern of the Coachella Valley Water District since the mid-1990s, with close monitoring of ground water required to keep things on an even keel.

Over the past 40 years Indio has seen a profound change in the way land is used--what was nearly all agriculture is now about half urban and recreational (especially golf!) uses.

As the nearby Salton Sea reminds as (as it dehydrates into a toxic, dusty ecological disaster), water means everything in this corner of the southwest. If a long drought strikes, or water allocation patterns change (for whatever reason), a place like Indio, and its golf courses, could dry up and revert back to a place of date palms growing in a desert landscape.

1. Look for tools. You knew that Google satellite view maps would be useful, and you might even know that Google Earth has a fantastic image archive, but finding the Time Lapse version of Google Earth is a huge asset. Remember to search for a tool to help you with your task.

2. Vary the regional terms you use. There are a few documents about "land use" topics that are connected with Indio, but there area LOT more if you search for land-use in conjunction with a larger regional description ("Coachella Valley").

Search on!