Daniel M. Russell's Blog, page 28

March 22, 2021

Answer: Epidemic historical context?

The past doesn't repeat itself,

... but it sometimes rhymes. (You could look up the attribution yourself, but no matter the answer, it's disputed.)

So let's revisit the Epidemic Rodeo and see what lessons we might take away from these Challenge questions that came up last week.

1. In the Swine Flu epidemic of 1976, a strange new device was used to quickly give many immunizations to a large number of people. (You'll know it when you find it.) What was that device, and why aren't we using it to rapidly immunize people with the COVID vaccine?

My query was straightforward:

[ Swine flu vaccine device ]

Which gave a link to the CDC web page about the Swine Flu outbreak of 1976. In that page, there's an image of President Ford getting a regular injection, but there's also an image of a woman getting an injection from something that looks like a medical device from a science-fiction garage. It's described as a "jet injector," so my next query was:

[ Swine flu 1976 jet injector ]

which leads to a number of articles that describe the jet injector as a new piece of technology that would let thousands of immunizations to be given rapidly.

Swine flu vaccine being given by jet injector (1987). CDC

Swine flu vaccine being given by jet injector (1987). CDC Or this slightly happier looking view of a woman getting a Swine flu vaccine.

Or this slightly happier looking view of a woman getting a Swine flu vaccine.So why aren't jet injectors used everywhere, especially in these days when we need to immunize a LOT of people REALLY RAPIDLY?

The Wikipedia article about jet injectors tells us that the World Health Organization no longer recommends jet injectors for vaccination due to risks of disease transmission. That article goes into great detail about why jet injectors are at risk for cross-contamination and subject to the perversely named suck-back effect. "Fluid suck-back occurs when blood left on the nozzle of the jet injector is sucked back into the injector orifice, contaminating the next dose to be fired..." Not a great idea when you're unsure if the recipient has the disease or not!

Interesting tidbit: In 1936, Marshall Lockhart, an engineer, filed a patent for his idea of a jet injector after seeing similar devices. He called his gadget the hypospray. Thirty years later, Star Trek (TOS) series started to use its own medical jet injector device, also called "hypospray."

2. Can you find the first large scale program to immunize people from smallpox in the Americas? Who did it?

My query was:

[ history of vaccination programs ]

which led me to this fascinating timeline on the history of vaccination (by the The College of Physicians of Philadelphia).

It looks like this:

On this timeline, you can scrub back and forth and see a fairly complete list of the major historical vaccination efforts. It even includes the early (circa 1000 CE!) Chinese practices of variolation (that is, the deliberate inoculation of an uninfected person with the smallpox virus through contact with pustular matter.

If you look take the time to look through this extensive list, you'll find many early vaccination efforts (e.g., Cotton Mather's (1663-1728) smallpox variolations)...

But the first campaign or drive to immunize people in the Americas is clearly the 1803 expedition to the Americas by Francisco Xavier de Balmis.

Where we learn that ...

"King Charles IV of Spain commissioned royal physician Francisco Xavier de Balmis to bring smallpox vaccination to the Spanish colonies in the New World. De Balmis departed on a ship with 22 abandoned children and a host of assistants, planning to vaccinate the boys in sets of two throughout the trip so that fresh pustules would be available at any given time. He eventually reached Caracas. Despite only one of the children still having a visible cowpox pustule, De Balmis initiated South American vaccination. (All 22 children were eventually settled, educated, and adopted in Mexico, at the Spanish government’s expense.)"

Not only do we now know the earliest mass vaccination campaign (1803) but also the answer to our next Challenge...

An illustration made by by Francisco Javier de Balmis showing smallpox vaccination scars.

Wellcome Library, London

3. As we've learned, vaccine injectable materials often require special handling. The Pfizer vaccine requires a refrigeration between -80C and -60C. So, how was the smallpox vaccine transported in the answer to the previous question?

The somewhat remarkable answer is "in the bodies of 22 orphaned boys who were successively given the smallpox vaccine." And, even more amazing, only one of the boys had a useful pustule when they finally made it to Caracas. They came that close to not having transported the variolation material across the Atlantic.

This is such an amazing story that it just asks for verification and triangulation.

That's not hard to do. A quick search on the name:

[ Francisco Xavier de Balmis ]

leads to all kinds of high-quality sources about his life and the story of the expedition.

One paper (Aldrete, J. Antonio. "Smallpox vaccination in the early 19th century using live carriers: the travels of Francisco Xavier de Balmis." Southern Medical Journal 97.4 (2004): 375-379) tells the story. The abstract reads:

Realizing that the Spanish colonies were being devastated by epidemics of smallpox resulting in thousands of deaths, Charles IV, King of Spain, sent one of his court's physicians to apply the recently discovered vaccine. Without refrigeration, the vaccine was passed from one child to another (boys taken out of orphanages). Francisco Xavier de Balmis and a team that included three assistants, two surgeons, and three nurses sailed from Spain on November 30, 1803. They vaccinated more than 100,000 people from the Caribbean Islands and South, Central, and North America, reaching up to San Antonio, Texas, and then traveled to the Philippines, Macao, Canton, and Santa Elena Island, landing back in Cadiz on September 7, 1806. During his journey, Balmis instructed local physicians on how to prepare, preserve, and apply the vaccine, while collecting rare biologic specimens.

That's an amazing vaccination program for the early 19th century.

I couldn't find anything similar that took place before that time.

4. Yellow Fever epidemics have ravaged many places around the world forever. And while Yellow Fever used to be an enormous problem in New York, it isn't any more. Why not? Was it due to the success of the Yellow Fever vaccination program? Or what?

My query:

[ yellow fever history in New York ]

The New York History site tells me that YF finally was extirpated when NY got rid of standing water for mosquitos.

“More sanitary conditions and the draining of stagnant waters have largely decimated the mosquito populations that once plagued the city.”

The New York City data site tells us that there was a Yellow Fever epidemic from 1795 to 1804.

"Although yellow fever killed dozens of New Yorkers in the first year, people were reluctant to publicize the epidemic due to fear of business loss and of mass immigration away from New York. Doctors also didn’t initially realize yellow fever was spread by mosquitoes, many hypothesizing it began from rotting coffee or from poor sanitation in slums”

Even worse:

"Between 1668 and 1870 there were at least 25 outbreaks in New York, and there were devastating outbreaks in such cities as Philadelphia, Memphis, and Charleston. The New Orleans epidemic of 1898 involved almost 14,000 cases with 4000 deaths, whereas the epidemic in the lower Mississippi valley in 1878 resulted in 20,000 deaths and economic losses of almost $200 million."

So it wasn't clear WHAT was causing Yellow Fever. To find that, I did:

[ who found yellow fever cause ]

and learned from an article published in Bulletin de la Societe de pathologie exotique, Centenary of the discovery of yellow fever virus and its transmission by a mosquito (Cuba 1900-1901), that it was Walter Reed's commission about Yellow Fever that figured out it was a virus, carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito that could transmit the disease. (Yes, THAT Walter Reed, for whom the large Army medical center in Washington DC is named).

Walter Reed, ca. 1900

Walter Reed, ca. 1900

If this mosquito is transmitting Yellow Fever, then the fix for Yellow Fever is to eliminate the mosquitos, which means removing stagnant pools of water where they can breed.

THAT led me to search for:

[ mosquito control New York ]

which gave me a lot of results, but mostly for present day pest controls... so, to limit it to historical information I modified the query to be:

[ mosquito control New York history ]

which gives lots of results, but to find the ways in which they controlled yellow fever took some digging.

I finally found an authoritative paper "Yellow Fever Crusade: US Colonialism, Tropical Medicine, and the International Politics of Mosquito Control, 1900-1920." which tells us that once Walter Reed figured out that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was responsible, that led to a massive mosquito control effort in Cuba (which US forces occupied following the Spanish-American war). Remarkably, that effort (removing standing water or spraying oil on stagnant pools) reduced yellow fever deaths to ZERO in less than one year. This program was transferred to the Panama Canal project (which was being built at the same time) with equal success, completely changing the way people tried to control yellow fever.

Now I want to learn about the history of mosquito control efforts in New York:

[ mosquito control New York history ]

which led me to a paper in the Journal of Urban Health, "The control of mosquito-borne diseases in New York City" and in there I found that:

"Mosquito control began in New York City in 1901. Large-scale efforts to drain marshlands occurred through the 1930s, and aerial application of pesticide occurred as early as 1956. Components of early mosquito-borne disease control were reimplemented in 1999-2000 in response to an outbreak of West Nile virus.."

Ah ha! We actually addressed this in an earlier SRS Challenge: What are those lines in the bay? when I wondered what made the lines I spotted from a plane landing at JFK airport. Those were mosquito control ditches. But they dug primarily in the 1930s. What happened before 1930?

A little farther down in that previous paper, we also find the answer:

"Deliberate efforts to control mosquitoes in New York City began in 1901 to prevent malaria. The basic elements of mosquito-borne disease control implemented in New York City began in 1901: promoting public and health professional awareness regarding disease causation and prevention, establishing government laboratory testing capacity, reporting cases of suspected mosquito-borne disease to the New York City Department of Health, and mapping and eliminating or applying larvicide to natural and artificial mosquito breeding sites..."

In essence, the effort to control malarial mosquitos (which are Anopheles, not Aedes aegypti) had the fortunate side-effect of also controlling the yellow fever mosquitoes.

A vaccine for yellow fever wasn't developed until 1937, so it wasn't a mass vaccination program that saved the populace from yellow fever, it was simply a matter of getting rid of the mosquitos (although, as we saw earlier, that's not a minor effort!). It was a happy accident!

The lessons here are:

1. Sometimes historical searches need the term "history" in them. That seems simple enough--but it's often needed to remove results that are from current times (e.g., to get historically interesting results about the history of mosquito control, rather then just companies that are offering to do mosquito control for you).

Search on!

March 10, 2021

SearchResearch Challenge (3/10/21): Epidemic historical context?

"This isn't our first rodeo.."

... is sometimes said to describe a repeat of a situation that's complicated.

And that's the case with the COVID pandemic--it's not the first time the world has had a terrible time with large scale epidemics.

We touched on this a few months ago with our research into the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, but it's worth returning to the rodeo to gain a bit of historical context. As we've noted before, "history doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes"

(Attributed to Mark Twain, but probably James Eayrs. See QuoteInvestigator's analysis.)

So let's revisit the Epidemic Rodeo and see what lessons we might take away.

1. In the Swine Flu epidemic of 1976, a strange new device was used to quickly give many immunizations to a large number of people. (You'll know it when you find it.) What was that device, and why aren't we using it to rapidly immunize people with the COVID vaccine?

2. Can you find the first large scale program to immunize people from smallpox in the Americas? Who did it?

3. As we've learned, vaccine injectable materials often require special handling. The Pfizer vaccine requires a refrigeration between -80C and -60C. So, how was the smallpox vaccine transported in the answer to the previous question?

4. Yellow Fever epidemics have ravaged many places around the world forever. And while Yellow Fever used to be an enormous problem in New York, it isn't any more. Why not? Was it due to the success of the Yellow Fever vaccination program? Or what?

As always, we all want to learn from HOW you found the answers. Each one isn't difficult, but might require a bit of that SRS skillset. Tell us how you did it!

Search on!

March 6, 2021

Answer: When did which colors signal gender?

Pink? Blue? Other colors?

... these days, in the US at least, the colors of pink and blue have commonly-agreed upon gender meanings. Pink means female, blue means male. But as a friend asked recently, why?

Here is last week's Challenge:

Regular Reader Arthur Weiss seems to have a lock on my search intuitions. Like Arthur, my first search was1. Can you figure out the history of pink/blue meaning female/male? Has blue always signified male? Has pink always signified female?

[ pink blue colors gender history ]

Which led to the unexpected finding that blue once signified female while pink signified male!

As Arthur pointed out, "this topic is so surrounded in gender politics I wanted a range of sites to feel certain." Excellent point. Whenever you're searching on a contentious topic, you want to get a spectrum of perspectives.

I first read the Smithsonian article, When Did Girls Start Wearing Pink. In this article, Jo B. Paoletti, a historian at the University of Maryland and author of Pink and Blue: Telling the Girls From the Boys in America... [points to] a June 1918 article from the trade publication Earnshaw's Infants' Department which says that, “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.” Other sources said blue was flattering for blonds, pink for brunettes; or blue was for blue-eyed babies, pink for brown-eyed babies, according to Paoletti. She goes on to say that pink became the preferred color for girls sometime in the 1940s.

There are several other articles that support this timeline and argument. Weiss points out that the GenderSpectrum website goes even further, saying that blue/pink only became gender specific at the start of the 19 century--before that it was a neutral, unisex white. It was only around the time of World War I that the colors of blue and pink became more gender specific.

[image error] An archival birthday card from the 1910s with a girl in a blue frock, and a boy in a pink suit.

Arthur mentions research by Marco Del Guidice using a database of five million books printed in American or British English from 1800-2000 where there was a lack of any mentions of “pink for a boy”, even though from 1890 onwards there were increasing mentions of “pink for a girl”.

This got me to thinking, could I find evidence in the historical book collection at Books.Google.com? At the Books site I did a bit of filtering by Custom Time Range (in the example below I'm searching from Jan 1, 1900 - Jan 1, 1918 and using the AROUND operator to find the term blue near boy (and then did the same for pink and boy, then blue and girl, then pink and girl).

As you remember, the AROUND operator searches for the first term ("blue") within 5 terms of the second ("boys"). That number (5) is the "radius"--that means a matching term is either 5 before the other term, or 5 behind it. I believe the maximum radius is 10 (but I have to check that).

In just a couple of minutes of searching, I was able to find multiple hits (far more than Del Guidice did, apparently). Here are a few, the first shows how, in 1919, pink was for boys and blue for girls:

[Sara Lee said] “…I’ve put a blue bow on my afghan. Pink is for boys…” from The Amazing Interlude, Mary Roberts Rinehart, 1919 - ( p 15)

However, just six years later we find:

“What is the proper colour for boy babies? I want to make a little sweater for a baby that has just arrived. Blue is for boys: pink for girls.” The Golden Book Magazine Volume 2 (1925)

and...

“Whether the child is a boy or girl sometimes determines the color the mother will choose. For infants, pink is used for boys, blue for girls…” (p 88) Merchandise Manuals for Retail Salespeople: Infants and children's wear By Werrett Wallace Charters · 1925

Arthur also found the wonderful Wikipedia article on Pink and Blue as Gender Signifiers (which is basically a long list of dates, colors and genders). As is shown in that list, there are no sources saying pink for boys past 1941. But that list also shows that the color/gender assignments were not very fixed before--it was possible to find color assignments going both ways.

However, after 1941, things seem to have settled into the current standard: blue for boys, pink for girls. (It sure took a while to get there!)

2. And, if I remember correctly, young boys used to wear dresses (or some kind of gown) in their early photos. When did that practice stop? (Or has it?)

US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in a dress as a young child.

US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in a dress as a young child. (1884, age 2)

[ dresses for boys Wikipedia ]

This took me to a link to the Wikipedia article on breeching which discusses why boys wore dresses. Bottom line: it's easier when they're infants), and when this clothing pattern stopped, as with the color coded gender, around the time of the First World War.

As the Wiki article pointed out, traditionally, switching from dresses to breeches "was an important rite of passage in the life of a boy, looked forward to with much excitement, often celebrated with a small party. It often marked the point at which the father became more involved with the raising of a boy."

According to an article by Kaushik Patowary in Amusing Planet "It wasn’t until the end of the First World War, that parents began to dress their child according to their sex. But as the 20th century progressed, gender distinction once again declined as parents began to clothe their child androgynously in t-shirts, jeans, sweatshirts and sneakers."

1. For contentious topics, be sure to get multiple sources and compare/contrast their evidence. Anything involving gender and signifiers of gender is going to get complicated. Here, I looked at around 10 different pieces of content before writing this up. Be sure to cross-check!

2. When searching for evidence of change across time, Books are a great resource--especially since you can filter by time range.

3. The AROUND operator works in the Books corpus as well. With AROUND, you can find the pieces of evidence you seek, with words appearing near to each other in the text.

Search on!

February 24, 2021

SearchResearch Challenge (2/24/21): When did which colors signal gender?

As endless gender recent reveal parties have shown us...

... these days, in the US at least, the colors of pink and blue have commonly-agreed upon gender meanings. Pink means female, blue means male. But as a friend asked recently, why?

Or, as a way to figure out the why perhaps we can think about it this way: when did pink come to mean female and blue come to mean male? This leads to today's SearchResearch Challenges:

1. Can you figure out the history of pink/blue meaning female/male? Has blue always signified male? Has pink always signified female?

2. And, if I remember correctly, young boys used to wear dresses (or some kind of gown) in their early photos. When did that practice stop? (Or has it?)

As usual, we'd really like to learn HOW you found the history of these gender signals. What was the search process you followed? Let us know.

Search on!

February 17, 2021

Answer: Two difficult to find objects?

That was fun!

Last week I posed two Challenges, both of which I thought were fairly tough--but the SRS Regular Readers found it fairly straightforward. Kudos to you! (At the end I'll come back to why I found this difficult, and why I think you found them straightforward.)

Here are the Challenges from last week:

1. In my reading I keep seeing references to a compilation of short stories that was put together by the English playwright, novelist, and short story writer Somerset Maugham. The collection is called Tellers of Tales: One Hundred Short Stories from the United States, England, France, Russia and Germany. (1939) It's easy to find references to it, but I'd really like to read it. Can you find a full-view copy of this book that I can read online (without having to spend a zillion dollars)?

I'm going to quote Regular Reader Arthur Weiss on this (lightly edited):

First I tried Google Books and Project Gutenberg - as the anthology should be out of print. Then I just did a Google search:

["teller of tales" "One Hundred Short Stories from the United States, England, France, Russia and Germany" Maugham ]

And up came: One Hundred Short Stories...

Hard copy versions are available to purchase from a few places for around $50 or less at like Biblio.com and other sites.

Maugham's own works are easier to find online - but this was an anthology. You can see his collected stories at FadedPage.com

LESSON: The Internet Archive now includes much much more than archived websites.

That's a good lesson there at the end: The Internet Archive DOES have much more than you might expect. I promise to queue up a post about the Archive in the near future. Stay tuned.

Regular Readers found this pretty straightforward; there are multiple variations on this search that will work. Interestingly, this also leads to Amazon and eBay (you could buy a used copy there), and to Hathi Trust (but it's not in full-view). Like you, the only full-view copy I could find is at the Internet Archive.

2. Also in my reading, I came across a word that seems to describe some kind of very old fastener. The word is "latchet," but it does not have anything to do with shoes (e.g., a string used to fasten a shoe) or any kind of fish. It took me a while to find a good image of what a latchet fastener is--can you find one and tell us what it is? And for extra credit, where and when were latchets primarily used?

The Readers also found this fairly easy to discover. There were two strategies:

A. [ latchet fastener ] B. [ latchet -shoe -sandal -fish ]

They both work perfectly. The A strategy just includes a description of what a latchet is ("fastener"), while the B strategy removes terms that would lead to false positives (I told you it wasn't a shoe, so -shoe makes a lot of sense).

And what's a latchet? When I did this search [ latchet fastener ] , I ended up looking to Google Books and finding a number of books that talk about latchets. I learned quickly that it was a Celtic fastener that holds two parts of a large cloak or coat together. That led me to The Archaeology of Celtic Britain and Ireland, where I found this illustration on page 151:

Interestingly, this book points out that latchets usually had spirals of wire ("which experiments have found to be highly effective"), but that few of the spirals have survived.

Thus, images of latchets such as the one on the Irish stamp:

or the one from the British Museum (and found on the Google Cultural site; see also this different latchet at the British Museum web site, which has a great zoom function)...

are both missing the spiral wires that "latch" the pieces of clothing together. Still, they're beautiful, and capture the desire of people in pre-history to create lovely things.

Why was this hard for Dan?

I was impressed by everyone's skill at finding these "difficult to find" objects. So... why this tough for me?

Not excuses, but background!

When I started searching for the Somerset Maugham book, I also assumed it was out of copyright and would be in free view on Google Books, so I started there, and spent a fair bit of time looking in there trying to find the free view version... which, I discovered, doesn't exist in that collection.

Next I went directly to Hathi Trust... and found the same thing.

Eventually, like you, I looked in the Archive.org site and found it there. I know they have a more liberal interpretation of copyright than the other sites, but I figured everyone else would recap my search... but NO! You went straight to the Archive and found it.

Lesson: Start your search broadly and then narrow; rather than what I did, which was to start narrow and only after a couple of failures, search broadly. In particular, do NOT assume those important properties that undermine your search (such as "it's out of copyright").

Second, when I started looking for the latchet I had two problems. First, I ran across the word while reading a book.. which unfortunately spelled it as "lachet," which is an alternative spelling of the shoe binding. It took me a while to figure out that that's the not the correct spelling for the thing I was searching for. Second, I wasn't 100% sure what a latchet (or lachet) even was. It was mentioned in a text that didn't provide a lot of context--all I knew is that it was Celtic and used to connect a piece of clothing, but not a part of a shoe. Once I figured out that it was spelled LATCHET, I then got sidetracked by all of the meanings of latchet that are about shoe fasteners. This was a bit of a false lead because there's plenty of content around historic latchet shoes (e.g., this page about 17th century Scottish shoes!).

It was only after reading further in the text that I realized that the latchet under discussion significantly pre-dated the 17th century. As I read, I finally learned that the story was about the 6th Century. Big oops on my part.

Lesson: Check your spelling (especially when you're searching for a term that has alternative spellings), and be sure that what you're searching for is... well... exactly what you're searching for!

What does this mean for my estimate of the difficulty level?

I think I gave you a bit too much help! I told you that it was spelled "latchet" and that it didn't have anything to do with shoes. Big tip. You were able to take advantage of the little clues, just as you should.

And I bet you started your book searches broadly (as I always tell you to do), and didn't make my foolish mistake of assuming that I knew more about the book than was true.

Ah well... Live and learn.

I hope you learned as much about searching for "difficult to find" objects as I did! I'm reminded also that what's difficult for me, might not be difficult for you--and vice-versa.

Congrats to all who successfully found the objects. Excellent job!

Search on!

February 10, 2021

SearchResearch Challenge (2/10/21): Two difficult to find objects?

Every so often...

... in my work I'll search for something that takes a while to find. I save these for you! Here are two objects that I had to work a bit to find. In the process, I learned something about searching that I thought you'd enjoy. Can you find these as well?

1. In my reading I keep seeing references to a compilation of short stories that was put together by the English playwright, novelist, and short story writer Somerset Maugham. The collection is called Tellers of Tales: One Hundred Short Stories from the United States, England, France, Russia and Germany. (1939) It's easy to find references to it, but I'd really like to read it. Can you find a full-view copy of this book that I can read online (without having to spend a zillion dollars)?

2. Also in my reading, I came across a word that seems to describe some kind of very old fastener. The word is "latchet," but it does not have anything to do with shoes (e.g., a string used to fasten a shoe) or any kind of fish. It took me a while to find a good image of what a latchet fastener is--can you find one and tell us what it is? And for extra credit, where and when were latchets primarily used?

I'm curious how hard you find these two Challenges. Both gave me some trouble, maybe because I didn't have much context for either search.

If you locate these two things, let us know HOW you did it. (I'll reveal a couple of my missteps next week in the answer.)

Search on!

February 3, 2021

Answer: A war on pests?

When too many animals group together, it can be a problem.

[ Comment: Sorry this was a delayed by a week. It's been a busy time. ]

This week's Challenge highlights a couple of wrong-place & too-many times when people went to work to fix the problem, but it completely and utterly failed. These aren't hard, but are pretty amazing in their details. Can you figure out what's going on in each of these Challenges?

1. Too many birds really can be a problem. In one famous incident, an entire "War" was declared on a particular kind of bird. Big guns were brought out, the campaign planned, thousands of shots were fired, and it all ended in a dismal failure. Where was this war? What kind of birds were being fought? And in the end, what happened?

This wasn't too hard, but fascinating to learn about. I'd heard about a kind of "war against big birds that ended badly," and so was naturally curious to learn more.

[ war against birds ]

leads quickly to the Wikipedia and Scientific American articles about the Great Emu War.

The short version of this: Shortly after World War I, large numbers of discharged veterans were given land by the Australian government to take up farming within Western Australia. Unfortunately, the emus (large flightless birds) were enjoying the farmer's fields as well.

By late 1932, there were 20,000 of them wreaking havoc on the wheat farms of the beleaguered veterans, and even these trained riflemen could not put a dent in their numbers.

The veterans asked for help from the Australian military, which was more than happy to send soldiers, machine guns, and ammunition. The "war" was conducted under the command of Major G. P. W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery.

Unfortunately, when the soldiers went to shoot the birds, they scattered effectively and evaded much damage. After the first attempt, the total number of emus killed was roughly 50--after several thousands of rounds fired. A couple of weeks later they tried again, with not much better results. Tens of thousands of rounds fired, and only about 1,000 emus killed. In the end, it took around 10 shots per each emu removed. The technology solution did not work well.

However, Meredith's official report noted that his men had suffered no casualties.

After 1929, exclusion barrier fencing became a popular means of keeping emus out of agricultural areas (in addition to other vermin, such as dingoes and rabbits). It proved to be cheaper and much more effective than shooting them.

This war was won by the emus.

A wonderful contemporary film showing the Army's Lewis guns in action.

There were, of course, other battles against birds. As reader anon0750032j pointed out, Mao launched a massive extermination campaign against "The Four Pests," ( 除四害). The four pests to be eliminated were rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. The extermination of sparrows is also known as Smash Sparrows Campaign ( 打麻雀运动) or Eliminate Sparrows Campaign ( 消灭麻雀运动). This was another kind of disaster--the lack of birds resulted in severe ecological imbalance and became one of the causes of the Great Chinese Famine. In 1960, Mao ended the campaign against sparrows and redirected the fourth focus to bed bugs. (That sounds like a futile campaign.)

Luckily, they didn't bring out the heavy artillery, or I'm sure even more damage would have happened.

2. Too many insects can be a problem as well, especially when then fly around en masse. Can you find the largest grouping of insects that caused enormous problems with the local agriculture? Why do those insects group together? And why do those groupings finally end?

I did searches very much like Regular Readers:

[ large insect swarms ]

And, like many of you, I found that locusts form the largest aggregation of insects. With a couple of clicks I found the U. Florida Entomology Department's Book of Insect Records, which tells us that:

The Desert Locust, Schistocerca gregaria, forms the largest swarms. In early 1954, a swarm that invaded Kenya covered an area of 200km2. The estimated density was 50 million individuals per km2 giving a total number of 10 billion locusts...

On the other hand... I also found a New York Times article documenting the 1875 locust swarm that was the largest recorded in North America. It was estimated to be 1,800 miles long and 110 miles wide (512,817 km2). That's equal to the combined size of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Vermont!

Of course, it's difficult to compare these estimates without good communications technology (to get a single measure of the swarm size at one point in time), but if the estimates are close to correct, the 1875 swarm in North America was about twice the size of the Kenya swarm.

In both cases, these swarms were immensely devastating, eating all of the crops--seeds, fruits, and even the fence posts.

And yet, in North America, a mere 28 years later, this seemingly indestructible enemy vanished. There hasn't been a sizable locust swarm in for over 100 years (see: Wikipedia article on Rocky Mountain Locusts). In fact, these locusts are now extinct, apparently due to changes in land-use patterns over the past 150 years in central North America which removed their breeding grounds.

My query about "why do these swarms happen" was:

[ locust swarm causes ]

Leads to a plethora of articles about relatively recent discoveries about locust swarming behavior. One source (LiveScience) points out that "[locusts] undergo a dramatic transformation when there are many other locusts of the same species nearby. The locusts shift from what scientists call the solitary phase when the locust is alone, to the gregarious phase when they swarm together.

As it happens, the specific signal that begins the shift from solitary to gregarious varies from species to species. The desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) can shift into the gregarious phase with a touch on the hind legs, while the sensitive area on the Australian plague locust (Chortoicetes terminifera) is its antennae. These triggers seem to boost levels of serotonin, the same chemical associated with mood in humans. That serotonin boost, in turn, causes locusts to start to move together, ultimately snowballing into ever larger accumulation that become damaging swarms.

NOTE: There's a 17-year cicada brood emerging this spring. It will be tremendous, and look like and sound like a swarm, but they don't typically cause problems. Luckily, aside from making a tremendous din, cicadas typically are harmless and represent a huge windfall food supply for other animals. They don’t eat crops (although they occasionally feed upon tree sap); they just want emerge into the sunshine, find a mate, create the next generation and die (incidentally, delivering a huge amount of food to animals that feast on cicada bodies).

I was in the Washington DC area during the last cicada brood emergence, and it's true--they can be VERY loud and eerie-sounding. But they do not bite. However, they do fly, and love to crawl around... which was surprising when I found a couple crawling up my leg just above my socks!

A 17-year cicada, coming out in North America later this year...in the millions!

A 17-year cicada, coming out in North America later this year...in the millions!

SearchResearch Lessons

This wasn't a difficult task, but there's a good tip here..

1. Use the most specific term you can to describe the phenomenon you seek. In this case, the term swarm was the perfect descriptor. Take note of speciality terms like this as you do your initial reading, and then use those terms for your second, third, and fourth queries.

Search on!

January 26, 2021

How to Find... anything. #2: How to find recipes and nutrition information

Introduction

Haven’t we all searched for recipes? Whenever we’re trying to get dinner just right, or when exploring a new culinary idea. Sometimes we’ll do comparisons (how do other people make dinner rolls?), or sometimes we are looking for the best source of a recipe we have heard about (what was the original “no-knead” bread recipe?). Then again, sometimes we are just on the hunt for dishes that include our new ingredient obsession--this week it’s porcini mushrooms (got a great deal at the Farmer’s Market!), but next week it could be broccolini, kohlrabi, or maybe we’re just looking for new ideas for strawberry desserts.

Image by Monicore from Pixabay

Image by Monicore from PixabayYou can keep that trusty soup-stained cookbook on the shelf, it might have family heirloom recipes that you can’t find online, but this chapter is about how to find (and sometimes filter) recipes beyond the scope of even the largest cookbook you might have on your shelf. You can even please those picky eaters by improving your web search results to show recipes based on ingredients, cooking time, or calorie preferences.

Practical tip: While we’re going to talk about searching for recipes and nutritional information, if truth be told, when we find a recipe we like, we make a copy of the online recipe (with attribution and any production notes we learn along the way). Why? Recipes have an unfortunate tendency to disappear on the web. Besides, if we really like something, we’ll probably make it again. Back up your recipes by having local copies, if only so you can re-find it easily. Or import them in a recipe app so you can edit, organize them, share them across devices and have a backup in the cloud.

_______

What are recipes?

For the purposes of this chapter, a “recipe” is any written down list of instructions and ingredients that you use to put together a particular dish. It might be extensive and careful, or it might be minimalist with just a few clues about how to put together a dish. For our purposes, recipes are easy to find--just use the term “recipe” along with whatever you want to look up specifically.

Notice that some recipes (such as Mark Bitman’s excellent collection) are more guidelines to entire categories of food, rather than just a simple step-by-step recipe. Each recipe tells how to make the dish, but also ways to vary it and make many different variations on a theme. They’re on the borderland between a cooking encyclopedia and a recipe box.

On the other hand, some recipes have tons of information about how to make that particular kind dish--they’re a little like mini-tutorials in the Spend With Pennies or Epicurious web sites. These recipes often have videos to show techniques, or background information on the cultural aspects of the recipes. Fascinating stuff.

And sometimes you want to look up a particular technique that’s linked to a food. What really is “pressed duck” after all? Can I make it at home? How about phyllo dough? In these cases, you also want a recipe, but you REALLY need to know the technique as well. For such technique-heavy recipes, you want one of these “enhanced” recipes.

_______

What is nutrition information?

As you’re cooking, or planning on cooking, there are times when you’d like to know what exactly it is that you’re putting into your dish. It’s fairly easy to find the nutritional information for your ingredients with a query like this (suppose you’re making a passion fruit mousse):

[ nutrition passion fruit ]

The result will have a panel on the right hand side of the search results page--it it look like this:

Note that this will work for many fruits, vegetables, meat, fish (etc.), not ALL possible foods have detailed nutritional information that can be found on the Google knowledge panel. As of this writing dragon fruit (a popular fruit native to Mexico and Central America, it goes by many names, including pitaya, pitahaya, and strawberry pear) doesn’t have detailed USDA information, although this will probably change over time.

But the USDA site does have an incredible range of nutrition information about foods that you might not expect. Check out: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/ for full details. (For instance, did you know that goat meat has 143 calories / 100 grams?)

By the way, using the USDA site you can also find that dragon fruit has 260 calories in each 100 grams of fruit, and is high in calcium to boot!

_______

Recipe Search MethodsBroadly speaking, these methods are all ways to translate what you know about an educational need into search-engine specific strategies.

1. Search by dish: This is often the way people think about cooking: “I want to make lasagna” or “I want to make pad thai.” Unless you’re searching for a dish that’s incredibly obscure, a good search is something like this:

[ recipe for lasagna ]

[ recipe for pad thai ]

Note that if you’re searching for a particular kind of national dish (e.g., goulash, which in Hungarian is gulyás), try searching for the name in the language of origin:

[ recipe for gulyás ]

If you can read the local recipe language, even better search in that language to find possibly a more authentic version. Usually you’ll find sites that are dedicated to transcending national boundaries--in this case, you’ll find recipes that tell you how to make an authentic Hungarian gulyás, along with helpful tips about how to substitute location-specific ingredients. (e.g., do you actually need to use Hungarian paprika?)

To find recipes within a given country, use the site: operator to search ONLY in that country. Just use the country code. (List of all country codes.) Note that you’ll have to use the local language word for “recipe.” For example, here’s how to search for Bolognese lasagna recipes from Italian web sites.

[ ricetta lasagne alla bolognese site:.IT ]

2. Search by ingredient: So you couldn’t pass up the rutabaga at the farmer’s market but you’re not exactly sure what to make with it? Now you can slice and dice your farmer’s market bounty into tasty dishes by searching by ingredient. Simply type rutabaga into your search and get plenty of ideas.

[ recipes that use rutabaga ]

This works especially well when you’ve got a few random ingredients in your kitchen and need to find a recipe that uses them. In this case, just list all your ingredients, and see what you can discover! For example:

[ recipes rutabaga spinach cheese ]

3. Search by holiday or event: Hosting a baby shower or event and need to whip up some mouth-watering dishes to feed 50? Simply type the event name + recipes and you’ll see plenty of dishes.

[ baby shower recipes ]

[ kids birthday party recipes ]

[ traditional Swedish holiday recipes ]

4. Search by calories: Are you trying to consume fewer calories or have less fat in your diet? Search for recipes with descriptive terms. Examples:

[ lasagna recipe with fewer calories ]

[ lasagna recipe healthy ]

[ lasagna recipe less fat ]

5. Search by cooking time: When you’re pressed for time, you might want to find recipes that can be done in a certain amount of time. Here, the trick is to search for recipes with a time that’s specified. When you do these searches, try to use times like “30 minutes” or “1 hour” since that’s what people usually write. Searching for recipes that take 48 minutes to complete probably won’t work well. Here are some sample timed recipe searches:

[ recipes under 15 minutes ]

[ stew recipe 2 hours ]

[ vegan chili recipe under 3 hrs ] — hrs is a common abbreviation

You can also use descriptions of the amount of time:

[ soup recipe long slow ]

[ slow food confit recipe ]

6. Search by favorite chef or restaurant: A handy search method is to search by celebrity chef name or the name of a restaurant that has a dish you want to emulate. You can’t always find the exact recipe, but there’s probably a pretty good version of it out on the internet.

[ recipes by Poilâne ] (note that [ recipes by Poilane ] also works)

[ recipes by Jose Andres ] (or, José Andrés also works)

[ recipes by Greens Restaurant ]

7. Search for video: Learning a cooking technique is usually MUCH easier if you have a model to follow. Remember to search in videos to learn the techniques or methods you want to learn.

In Videos:

[ how to make paneer ]

[ how to make an omelette ]

[ how to make strudel dough ]

8. Search by images: Looking for a picture of something will often let you hone in on the thing you want to make, but don’t know the name! For instance, if you’re looking for a kind of cheese appetizer that came in a little cup-like thing with turned-up corners, a search like this will get your an answer quickly:

Note the second row of suggestions (party, toothpicks, easy, prosciutto, puff pastry, etc.). Those can also be very handy in finding what you seek.

Searching for images is also a very good way to learn how to plate and present the food in an aesthetically pleasing way. We start eating with our eyes first, think when you go to a great restaurant and their presentation of a dish.

It’s also a great way to learn what a particular kind of food / fruit / vegetable looks like--it will make your shopping experience much simpler if you can recognize it in the market! We were looking for a Buddha’s hand fruit, but didn’t quite know what to look for in the grocery. This is what it looks like:

9. Search by cooking technique or cooking tool

Many times you want to expand your knowledge of a cooking technique (e.g. sous-vide) or a tool (cast iron). Other times you are a big fan of a particular cooking technique, (e.g. steaming) or you are cooking at a friend or family’s location or you are travelling and cooking in a rental and you have access to a limited set of tools or, maybe to a set of tool you do not know how to use (pressure cooker)

[ cast iron peppers]

[ steamed broccoli]

[ pressure cooker rice]

[ slow cooker chili ]

10. Search within your favorite recipe website

This search is a bit different because it assumes you have a favorite or a set of favorite recipe websites. The more you search for recipes the more you will learn which ones you like--then you can use the site: operator to search within them.

Some recipe websites are subscription based, so not all recipes and techniques are available for free. Sample searches that we use inside a site are:

[ site:epicurious.com vegetarian bean chili ]

[ site:nytimes.com no knead bread ]

[ site:jamieoliver.com hot cross buns ]

_______

Conversions: How many tablespoons in a cup? Or, going from ounces to grams!

The quantity of a recipe can be written in different measuring systems. So you might need to convert quantities from one measurement to another. European recipes often give quantities in metric measurements (grams), while US recipes often give them in quantities (cups, tablespoons).

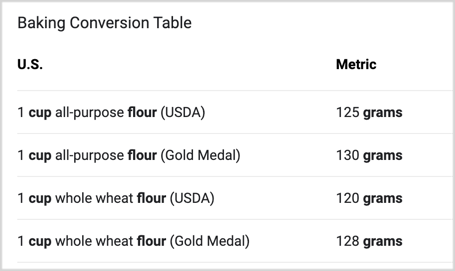

Note that when doing weight measures to volume measures you will have to look up the conversion rate. If a recipe asks for 500 grams of flour, but you have only US measuring cups, you’ll have to figure out what the conversion rate is. A quick trick is to do this query:

[ grams of flour in cups ]

Google will then show you a handy conversion chart:

Of course, if you want to just convert from grams to ounces (or the other way around), you can just do the conversion query:

[ 25 grams in ounces ]

[ 1 pound in grams ]

This is also really handy for conversions within the English (or Imperial) measurements:

[ 16 tablespoons in cups ]

Or you can ask a question:

[ how many cups in a pint? ]

Another kind of common searches while cooking are for ingredient substitutions. For example, you want to make tamales and you do now have or cannot easily find corn husks. What can you do? This works well for exotic ingredients that you might not have, such as corn husks (used in tamales), or asafoetida (an Indian spice):

[ tamales corn husks substitution ]

[ tamales corn husks alternative ]

[ asafoetida substitute ]

Cooking Techniques

A common search is for methods of doing particular skills in the kitchen. For example, if you’re not comfortable with your knife chopping technique, consider doing a search on how to handle knives. A search on:

[ How to cut an avocado ]

[ How to cut a bagel ]

[ How to chop onions ]

might avoid a trip to the emergency room. In the same vein, learning how to sharpen a knife, mince garlic, or make a perfect crepe are all easy searches.

Recipe apps

Recipe app web, desktop, or mobile apps allow you to write, organize, store, and import recipes from the web. These apps can save you a lot of time and help you to build your own cookbook. You could start by typing your grandma’s favorite recipe on the app and use it on your smartphone when cooking, even when you’re not in your own home. Apps also allow you to quickly scale a recipe depending on how many people you need to cook for.

These apps generally allow you to export and share your apps with your friends and family including adding pictures.

Dealing with variation between recipes

As you’ve probably noticed, there can be many different versions of a recipe. Few people agree about the right way to roast a chicken, make cupcakes, or bake bread. Part of the joy of cooking is learning to understand the variations between recipes.

For this reason, we typically look at more than one recipe when making a particular dish. A search for something simple, say…

[ recipe enchiladas ]

[ recipe lasagna ]

Will quickly show you the huge variation in styles, ingredients, and methods (do you want fast, low-fat, for parties, meatless, with red sauce or bechamel).

Don’t be intimidated by the number of different variations on the theme, but use them to compose and create your own masterpiece.

Enjoy!

_______

Summary

In this chapter we’ve shown you how to search for:

Nutrition information

Recipe search methods

1. by name of dish

2. by ingredients

3. by holiday or event

4. by calories

5. by cooking time – times, durations

6. by chef or restaurant

7. search for videos

8. search for images

9. by cooking technique or tool

10. search inside a recipe website

Conversions (metric to English, and back)

Cooking techniques (and tools)

Recipe apps (to manage your recipes)

Dealing with variation between recipes

_______

Key lessons:

A. There are many ways to search for a recipe--by dish, ingredients, style, time-to-cook, etc. Just add in the extra search terms to search by those different properties.

B. Using the conversions methods (e.g., grams to ounces) is incredibly useful when using metric recipes. This is just as true to convert measurements within the English units as well. (We can never remember how many tablespoons are in a cup. Can you?)

C. Search for images and videos to help deepen your understanding of what the different foods and techniques are. The number of methods and technique videos are astounding. They often can teach you a method that was previously available only by a long apprenticeship. Watch those videos before trying it on your own. (There are important methods to know, ones that could prevent a cooking injury or make that omelette just perfect.)

January 20, 2021

SearchResearch Challenge (1/20/21): A war on pests?

Too much of anything can be a problem...

... Too much water in the wrong place at the wrong time is a flood. And too many birds in the wrong place can be a problem as well.

This week's Challenge highlights a couple of wrong-place & too-many times when people went to work to fix the problem, but it completely and utterly failed. These aren't hard, but are pretty amazing in their details. Can you figure out what's going on in each of these Challenges?

1. Too many birds really can be a problem. In one famous incident, an entire "War" was declared on a particular kind of bird. Big guns were brought out, the campaign planned, thousands of shots were fired, and it all ended in a dismal failure. Where was this war? What kind of birds were being fought? And in the end, what happened?

2. Too many insects can be a problem as well, especially when then fly around en masse. Can you find the largest grouping of insects that caused enormous problems with the local agriculture? Why do those insects group together? And why do those groupings finally end?

These Challenges can take you far into some fascinating rabbit holes (another kind of pest in some locations), but keep your wits about you and let us know how you answered these Challenges.

As always, we're interested in how you found the solutions to these Challenge questions. Let us know in the comments.

Search on!

January 18, 2021

New Series: How to Find... anything. #1: How to find Do-it-yourself information

Welcome to a new series of "How to Find... anything" posts.

My friend Mario Callegaro and I have been talking for years about pulling together a series of posts that are all "How to Find..." mini-tutorials for a number of topics. Our plan is to put out about one post each week, each post covering another specific "How to Find.." topic area.

This week, for example, is all about How to Find "Do-it-yourself (DIY) information." In future episodes we'll discuss how to find other topic area like medical information, or educational content, or recipes, or travel information.

As we've taught people how to search over the years, we've noticed that for every special domain (DIY, medicine, education, recipes, travel) that there's often something else to know about searching in that area--some additional bits of information about the domain that would help you search more effectively.

So, to address this, we've written about 10 such posts, and will put them out at about one post per week for the next couple of months.

At the end, we'll pull all of the searching tips together into a compendium that will be very SearchResearch-like as a summary.

THEN we hope to pull all of these posts together into a single document that you'll be able to print for yourself, use in your classes, or (with luck) buy as an online book.

Our hope is to provide a bunch of easy-to-read information about how to search in a given area. So we're really looking for feedback about each chapter, and about the idea overall.

Please leave comments in the comment area below. We'll read them with interest, and will try to make this series into something truly useful for everyone.

Enjoy.

Dan & Mario

How to find: Do-it-yourself information

A common thing people search for is “how to” information. Sometimes called “do it yourself” (DIY), this kind of how-to-do-something is an important part of how people share their craft with others. In the past few years, plenty of web sites have sprung up to teach people how to sew, repair broken appliances, darn socks, or do thoracic surgery. Once this kind of information was the area of hobbyists and obscure, difficult-to-find speciality magazines and specialized books. But now, the DIY and Maker movements have extended boundaries with some sophisticated DIY information that’s easily findable and widely available. (Think about examples like “how to build your own surfboard,” “how to set up your own Minecraft server,” or “how to do fire spinning.”)

Sometimes, getting the DIY information rapidly is critical--the water is gushing out of my plumbing NOW and I need to stop it instantly. Most of the time, getting the DIY information is leisurely--you can learn how to fly a drone or build a Minecraft server pretty much any time. Other times you want to save time and money and fix or build something yourself, instead of calling a company or person to do that for you. In the get-it-to-me-now case, you don’t want to spend a lot of time futzing around… and that’s why you’re reading this article now. In the leisurely case and save time and money case, you probably want to find pretty reliable “how to” information so you don’t crash your drone on its first flight, or spend lots of time building a broken server.

DIY--or “how to do it”--information tells you (or better yet, shows you) how to do some particularly skilled thing. Usually DIY info is for topics where it’s really not obvious how to do it (for instance, how DO you cut glass to make stained glass artwork?), mysterious (how do you make a fishing net out of a long string?), or involves steps where doing it wrong is really dangerous or expensive.

Lots of DIY content these days is in video form, although printed manuals and how-to guides are sometimes easier to use.

While there are MANY kinds of DIY information, we’re going to look at just the most common kinds:

How to do a particular skill? (Think twirling a fire baton, riding a unicycle, replacing car brake pads, play a musical instrument, or how to strum a power chord on your electric guitar at max volume.)How to fix something that’s broken? (Your blender / TV / phone computer is broken. Your socks need repair. Your kitchen faucet needs replacing. What now?)

How to make something from scratch? (Learn to bake a cake, build an igloo, make the best paper airplane, or write a strong resume.)

How do you use a tool or piece of software? (You need to learn how to fix up old photos using a software photo editor. You’d like to learn how to use an awl correctly, without sticking it into your hand.)

Luckily, the internet is full of people who have created tutorials and written-up how-tos for even the most obscure topics. (Need to know how to take care of a pet spider? There are tutorials written for you. Really. If you're an arachnophobe, don't search for this.)

Consider what you already know. If you’re looking up DIY information about creating a new Mardi Gras costume, think about how much you already know. Are you a sewer? Do you have a closet full of needles and thread, ribbons and bolts of fabric? Are you already an expert in the field?

When starting a DIY search, first consider what kind of information you need. If you’re a beginner, you’re going to need an overview or quick introduction to the field, if only to learn the language and to assess whether or not this is a good thing to start doing. (It could be that you’re taking on something way over your head or budget. That’s the point of up-front research: Find this kind of thing out before sinking lots of time and money into a project. Learning how to bake bread is fairly straightforward; learning how to bake a beautifully decorated cake involves more time, money, and practice.) Check out the results all the way to the end. (Don’t be surprised by a suddenly large amount of time you need at the end of the recipe when your dinner party is TONIGHT.)

Once you’ve started finding your research, think about building up a collection of articles, evaluating which one(s) you think are the best. Are they in a language you understand? Is it clear what’s involved?

Pro tip: Always search for at least two or three different how-to articles (or videos) before diving in. It’s often the case that one article will illustrate the method in a way that doesn’t make sense until you read another take on the same topic.

Depending on what you are attempting to fix or a skill to learn, remember that most online resources are written by professionals or individuals very familiar with the topic. In case of doing electrical work, for example, you might want to disconnect the power first, before plumbing work you want to shut off the main shutoff water valve in your place, or before deboning a chicken for the first time you might want to watch some knife skills tutorials.

The less you know for a topic the more you want to search not only for the skill to learn or the component to fix, but also how to do it safely.

An example is the infamous “avocado cut” which is referred to in emergency hospital rooms as a knife cut on the palm hand when attempting to cut an avocado.

Start broadly: When I’m doing a DIY search in an area I don’t know much about, I start broadly, usually learning a lot about the field before I dive into the specifics. For instance, I know very little about knitting. So if I wanted to get into knitting as a spare-time activity, I’d first look up more general articles about knitting to get a sense for what’s involved. Use queries such as:

[ knitting overview ]

[ introduction to knitting ]

[ beginning knitting ]

(Here, the bold-blue text are the kinds of context terms that you might use to focus your search on a particular kind of result. I'll use this convention to point out aspects of the search you should pay attention to.)

I’d look at the high end to see the things I’d like to aspire to do one day, and then go back and look at the entry-level, or beginner’s level materials. Can I get there from here?

Dive in: If I already know what I’m doing (or if I’ve learned a lot already), I’ll start to dive into mechanics of searching for teaching material. I start broadly, casting out a wide net, and look for specialty sites along the way. Let’s take the example of guitar playing:

[ how to play guitar ]

[ guitar instruction ]

[ guitar lessons ]

And if you know what style of guitar playing you’d like to pursue, add that in as well:

[ how to play flamenco guitar ]

[ gypsy guitar instruction ]

[ jazz guitar lessons ]

Then, once you start to become more expert in the field, you can search for specifics, for example, a strumming technique that’s used in flamenco guitar playing is rasgueado--if you know that, use it in your search:

[ flamenco guitar rasgueado ]

Or, you can search for content that’s specifically labeled as advanced (or intermediate):

[ flamenco guitar advanced ]

Broadly speaking, these methods are all ways to translate what you know about an educational need into search-engine specific strategies.

1. Use specific terms that are used in your interest area. For instance, a cable weave is a kind of knitting stitch, while a cable braid is a way to manage all of those pesky computer cables under the desk. A “caliper” is part of a car’s brakes, but also a machinists measuring tool. You can use specific terms like this to get very on-target search results. (Caution: Be sure you know what your speciality term means! Don’t search for “penny whistle” if what you’re really looking for is “recorder.” Use [ define <term> ] to double check that your term means what you think it means!)

[ cable weave knitting pattern ]

vs.

[ woven cable headphone ]

2. Check out different kinds of media. Remember that there can be many different kinds of content. Often we turn to videos to find out how to do something physical (e.g., fix plumbing or learning a dance move), but printed documents can also be very helpful, especially when they’re specifically for the thing you’re trying to repair. Sometimes an exploded parts diagram that you can refer to is exactly the right thing. Also look for images for your topic. Electronics repairs often require a schematic diagram to help you understand how things are put together.

[ repair manual PDF Cuisinart blender ] (will find PDFs for a Cuisinart blender)

[ furnace schematic ] (Image search)

[ replace hose bib ] (Video search)

And while it might seem odd, remember that Books can be a useful place to learn how-to do something. Be sure to checkout Google Books. (Books.Google.com)

3. Look for Q&A or Forum sites. A Q&A (questions and answers) or Forum site can be a superb source of information. These sites are usually run by enthusiasts in that particular field to answer questions that come up for people.

[ forum tile repair ]

[ Q&A bicycle repair ]

[ DIY bike repair ]

4. Search for online communities in your interest area. Many social media networks (Facebook, Pintrest, Instagram, Tumblr, etc.) have communities of people with a shared interest. It’s simple to look on a social network for things like:

[ piano enthusiasts ]

[ woodworking ]

[ surfing ]

and get quickly linked into those communities, usually full of people who are more than willing to answer your questions.

5. Search for DIY content for your specific device / widget / gadget. People love to talk about their particular gadget. So it’s relatively straightforward to look for how-to information that’s keyed to a particular kind of device. Notice: Be sure the article you’re reading and the device you have are the same model (or release). Nothing is more frustrating than reading an entire how-to article and then figuring out that this was all for the previous version of the device… that you don’t own.

[ GoPro Silver how to time lapse ]

[ Photoshop CC tutorial ]

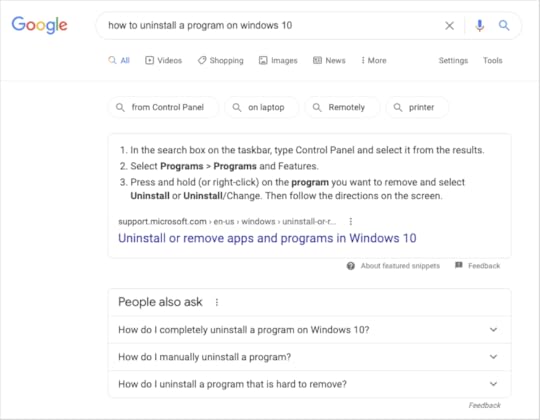

6. Google can sometimes provide a DIY for some common questions. As Google continues to improve its ability to extract information in response to common questions, you’ll start to see more answers being delivered in a form like this.

There are many videos on YouTube for your interest area. Be sure to look not just for individual videos, but also for channels that are on your topic.

You should know about the Stack Exchange sites. They’re Q&A sites on many topics. See: http://stackexchange.com/sites Another forum DIY site is reddit.com/r/DIY/ (And once you’ve found a good site, use site: to search inside it.)

Example:

[ site:sound.stackexchange.com/ how to record a piano ] - advice on recording a piano

Often a manufacturer will have a website that’s dedicated to supporting their gear. (A couple of examples: GoPro http://gopro.com/support/, Seagate http://www.seagate.com/support/ , etc.)

Popular DIY sites to consider (there are many--you could search for them). These are (currently) some of the most popular:

WikiHow.com

instructables.com

eHow.com

HowToGeek.com

HowTo.com

DIY.org

Note that DIY sites vary a lot by DIY area. DIY for arts-and-crafts projects are very different than ones for plumbing or gardening. Consider doing a search for your specific DIY area (e.g., “paper flowers” or “plumbing” in addition to DIY in your search).

MOOCs: A MOOC is a Massively Open Online Class. There are a great many MOOCs that will teach you specific things (e.g., how to code, how to do data analysis, how to play jazz guitar). Although they tend to be longer formats (multiple lessons), they’re often a great resource for life-long learning.

LinkedIn Learning: This is a commercial online education resource (you have to be a LinkedIn member to access it, and that costs real money), but much of their technical content is superb. (This is the product previously known as Lynda.com. LinkedIn has continued the Lynda commitment to quality online teaching.) If you’re looking for somewhat more in-depth how-to-do-it, this is a great resource.

Books: Search for books about [ how to …] on your topic.

Libraries, Colleges, Universities: Don’t forget about your local college and university courses, as well classes at your local library. Often these are free (or inexpensive) and can connect you with other enthusiasts in your area.

Another pro-tip: use the search [ learn to … ] pattern. For example:

[ learn to knit a scarf ]

Notice that we’re skirting the edges of searching for educational content. We’ll have another chapter on how to find learning resources / educational content. Stay tuned.

The outcome of a search will sometimes elicit a paid resource.

As we say in our forthcoming basic skills chapter, there is more content online that you can access because a part of it is under a paywall.

For example, there are many websites with tutorials and individual professors that you can hire to learn how to play a musical instrument. With more and more education content moving online, also accelerated by the COVID pandemic, you can have access to an almost infinite amount of resources.

Most paid resources have some free material that you can use to judge if that is what you are looking for and their quality. This is the case for sites that can teach you how to play an instrument or how to master a particular software.

Finally some sites provide a certification after you take some classes and generally pass an exam that you are qualified for that particular skill.In other words you can start to learn a new skill as a hobby or enthusiast and turn it around as a specific skill and even a new profession.

The more you get into your new skill or hobby, the more you will be interested in meeting people who share the same interest as you. For many topics that are exhibitions, fairs, and shows where you can go and attend talks, meet vendors, and meet other enthusiasts like you.

These exhibitions are now moved online because of the pandemic but they will likely resume as in person events after the pandemic is over.

Another major advantage of attending exhibitions, besides the social aspect of it, is that you can actually try and test tools, components, and machines in an easy and free fashion. Say, for example that you are into headphones. If you go to a headphone fair, you will have the chance to try many headphones in a relatively short period of time and ask questions directly to the manufacturer.

In this section we’ve shown you how to:

A. Start your search broadly, THEN narrow your focus.

B. Safety first

C. Use specific terms to locate the DIY info you need.

D. Look for multiple sources and kinds of information.

E. Search for online communities, which often have forums where you can ask you specific how-to questions.

F. Consider offline events such as exhibitions, fairs and shows

1. When searching for DIY, use context terms in your search to narrow what you’d like to find (e.g., terms like overview, introduction, beginning, advanced)

2. Use search patterns for DIY info: [ how to …] [ learn to …] [ lessons … ]

3. Use different kinds of media (not everything is in a video OR in text!) Check the web, videos, images, and books.

4. Look for Q&A (forum) sites on your DIY topic.

5. Look for online communities in your DIY area.

6. When trying to DIY something specific, put that into your search. (Especially model numbers or years.)

7. Consider searching for, and then using, specific DIY resources. (See list above.)