Litwit Lounge discussion

The Classics

>

Jean's Charles Dickens Challenge

"Little Nell" seems to have different personas/features to fit the plot at the time! The most usual way Dickens refers to her is as "the child" just as he refers to Quilp as "the dwarf", but on one occasion we learn that she is fully 14, and in a recent episode, she seems to have stunned a crowd of onlookers by her beauty. That hadn't come into anything up to now... She seems to be an accomplished reader too.

"Little Nell" seems to have different personas/features to fit the plot at the time! The most usual way Dickens refers to her is as "the child" just as he refers to Quilp as "the dwarf", but on one occasion we learn that she is fully 14, and in a recent episode, she seems to have stunned a crowd of onlookers by her beauty. That hadn't come into anything up to now... She seems to be an accomplished reader too.He had a penchant for what he saw a perfect young Victorian woman with all the Victorian virtues. They are frequently 17 years old though - which was the age at which Mary Hogarth, his sister-in-law whom he adored and never really got over, died. Writing these drippy girls into his novels seems to have provided a sort of catharsis. We just have to put up with them and wait for the next bit! :D

(Oh, I gather some people do think their goodness, kindness, neatness, good-with-a-thimble-ness is to be emulated. But it's not nearly as entertaining as his other characters' antics!)

I have a feeling Quilp is just going to be evil personnified the whole time. At least earlier villains such as Bill Sikes and Ralph Nickleby showed signs of remorse at the end!

Oh my I have just read chapter 33 with the description of the "dragon" Miss Sally Brass. Funniest thing I've read for a long time. Well since the feather-tickling episode anyway...

Oh my I have just read chapter 33 with the description of the "dragon" Miss Sally Brass. Funniest thing I've read for a long time. Well since the feather-tickling episode anyway...Increasingly I'm finding it's the quality of Dickens's writing which I love so much, rather than the plots. Whatever the basic premise of the book, Dickens is Dickens and will find that kernel of humour!

When I was beside myself consumed by giggles earlier this evening, Chris cheekily asked me, "Oh, have you got to the (view spoiler)?"

On the other hand, I certainly don't like novels with no plot. I think that's why I have such trouble with stream-of-consciousness stuff. But Dickens always tells stories - even in The Pickwick Papers there are stories after stories - and a linking one too.

Hard Times is a grim one though, as I remember, and shorter too, so perhaps not as many... "divertissements".

Another little bit of trivia:

Another little bit of trivia:chapter 33 - my favourite so far, as I said - includes in the first paragraph,

"the historian takes the friendly reader by the hand, and springing with him into the air, and cleaving the same at a greater rate than ever Don Cleophas Leandro Perez Zambullo and his familiar travelled through that pleasant region in company, alights with him upon the pavement of Bevis Marks."

In other words, we've finished with the Mrs Jarley and her waxworks for the moment, and we're going to follow some other characters (in fact, the lawyers.)

But quite apart from the admittedly engaging and joyous thought of leaping through the air holding hands with Dickens (!), who on earth are "Don Cleophas Leandro Perez Zambullo and his familiar"?

Answer:

They are characters in the novel, "The Devil on Two Sticks" by Alain-René Lesage.

The story goes that Don Cleophas Leandro Perez Zambullo, a Madrid gallant, accidentally frees a demon from captivity. In gratitude, the demon, (who is on crutches, because of falling from the sky after fighting with another devil) takes him up to a high place and makes all the roofs of Madrid transparent so he can see what is going on everywhere.

Maybe this was a popular novel of the time - presumably Dickens's readers knew what he was going on about. And it certainly sounds exciting!

And here it is! The devil upon crutches in England, or night scenes in London. A satirical work. Written upon the plan of the celebrated Diable boiteux of Monsieur Le Sage. In two parts. By a gentleman of Oxford. The second edition. Volume 1 of 2

Clearly in The Old Curiosity Shop the main characters are intended to be Little Nell and her grandfather. But in recent chapters they have not appeared at all, and the minor characters introduced are an absolute delight; the hypocritical monster of a teacher (with a crocodile of young ladies trailing in her wake) Miss Maltravers, who made Nell cry. Also the mannish Sally Brass is an absolute joy,

Clearly in The Old Curiosity Shop the main characters are intended to be Little Nell and her grandfather. But in recent chapters they have not appeared at all, and the minor characters introduced are an absolute delight; the hypocritical monster of a teacher (with a crocodile of young ladies trailing in her wake) Miss Maltravers, who made Nell cry. Also the mannish Sally Brass is an absolute joy, ".... the lady carried upon her upper lip certain reddish demonstrations, which, if the imagination had been assisted by her attire, might have been mistaken for a beard. These were, however, in all probability, nothing more than eyelashes in a wrong place, as the eyes of Miss Brass were quite free from any such natural impertinencies. In complexion Miss Brass was sallow - rather a dirty sallow, so to speak - but this hue was agreeably relieved by the healthy glow which mantled in the extreme tip of her laughing nose."...

and would have made a good wife for Quilp, I think,

""There she is," said Quilp, stopping short at the door, and wrinkling up his eyebrows as he looked towards Miss Sally; "there is the woman I ought to have married - there is the beautiful Sarah - there is the female who has all the charms of her sex and none of their weaknesses. Oh Sally, Sally!""

Or Dick Swiveller, with all his blather,

""I believe, sir," said Richard Swiveller, taking his pen out of his mouth, "that you desire to look at these apartments. They are very charming apartments, sir. They command an uninterrupted view of - of over the way, and they are within one minute's walk of - of the corner of the street.""

and at another time,

"Mr Richard Swiveller wending his way homeward after this fashion, which is considered by evil-minded men to be symbolical of intoxication, and is not held by such persons to denote that state of deep wisdom and reflection in which the actor knows himself to be,"

Oh my, that made me laugh! There are many more.

This middle section is very downbeat. (view spoiler), not to mention the descriptions of all the factories and the "slaves" who tend them.

This middle section is very downbeat. (view spoiler), not to mention the descriptions of all the factories and the "slaves" who tend them. Dickens's view of industrialisation seems to be that it dehumanises everybody. All the characters in the factory town are shadows of themselves as a consequence - even if they are kind they are ground down with filth and poverty. His portrayal of the country is the exact opposite.

You can almost trip up over all the portents and metaphors in these chapters, but it's all a bit grim. I think we can see in this novel, the roots of his later ones where he is even more condemnatory about the effects of the Industrial Revolution.

I do find myself missing Dickens's humour at the moment, and I'll latch onto each little cameos such as the one about the doctor (view spoiler) repeating what everyone else had already thought of, "the doctor departed, leaving the whole house in admiration of that wisdom which tallied so closely with their own. Everybody said he was a very shrewd doctor indeed, and knew perfectly what people's constitutions were; which there appears some reason to suppose he did." LOL!

Even Quilp is a delight, providing much needed comic relief. But how is it we can laugh at him when he is such a malevolent devil?!

A couple more interesting snippets:

A couple more interesting snippets:One of Dickens's fleeting cameos in chapter 28 is a Mr. Slum, who was trying to persuade Mrs. Jarley to employ his services as a poet in helping to advertise the waxworks. He shows her an example of his works, and says,

"It's an acrostic - the name at this moment is Warren"

There's a BIG clue there - Dickens usually alters the names a bit more! But apparently Mr. Slum was based on a person Dickens remembered from his horrific days at Warren's Blacking Factory!

By the time of this novel, however, the use of poetry in advertising was thought very old-fashioned, so Dickens was really poking fun at his characters by referring to a "convertible acrostic".

Another name puzzled me - Buffon. Clearly it was a pun, or a reference to a character whom I didn't know. In chapter 51, there's a conversation between the wonderful Sally Brass and her brother, and the chatterbox slimy Sampson butts in, talking about Quilp,

"He's extremely pleasant!" cried the obsequious Sampson. "His acquaintance with Natural History too is surprising. Quite a Buffoon, quite!" There is no doubt that Mr Brass intended some compliment or other; and it has been argued with show of reason that he would have said Buffon, but made use of a superfluous vowel."

Buffoon is from 1540s French for a clown - OK, I knew what a "buffoon" was - but not "buffon". It turns out that he was referring to a,

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopedic author...It has been said that "Truly, Buffon was the father of all thought in natural history in the second half of the 18th century".

Sometimes I wonder just how many of these "in-jokes" by Dickens just pass us by! :D

Is Quilp funny? Or just plain evil so you shudder? Well I find he's just so over the top. I suppose it's a bit like "booing" a baddie at the pantomime when you're a kid! You're scared of him but you love it too!

Is Quilp funny? Or just plain evil so you shudder? Well I find he's just so over the top. I suppose it's a bit like "booing" a baddie at the pantomime when you're a kid! You're scared of him but you love it too!Looking back over the last few chapters for an example, there's this,

"Mr Quilp shut himself in his Bachelor's Hall, which, by reason of its newly-erected chimney depositing the smoke inside the room and carrying none of it off, was not quite so agreeable as more fastidious people might have desired."

Now that puts a smile on my face, and I suspect that Dickens is going to continue to be sarcastic and present us with highly exaggerated, laughable images. It carries on,

"Such inconveniences, however, instead of disgusting the dwarf with his new abode, rather suited his humour"

and we get a description of the room filling with smoke,

"until nothing was visible through the midst but a pair of red and highly inflamed eyes, with sometimes a dim vision of his head and face, and, as in a violent fit of coughing, he slightly stirred the smoke and scattered the heavy wreaths by which they were obscured."

So now we have a ridiculous picture in our heads of an odd-looking man who has chosen to do this, to closet himself up in a poky little room, making himself extremely uncomfortable in the process. And in case we start to feel sorry for him, Dickens piles it on,

"In the midst of this atmosphere, which must have infallibly smothered any other man, Mr Quilp passed the evening with great cheerfulness; solacing himself all the time with the pipe and case-bottle; and occasionally entertaining himself with a melodious howl, intended for a song, but bearing not the faintest resemblance to any scrap of any piece of music, vocal or instrumental, ever invented by man."

Yes, I find this hilariously funny, even though he's evil and almost sub-human! There's another part near here where he's dancing around like a little demon or devil, but I can't quite put my finger on it at the moment.

Dickens seems to be detailing the horrific abuses of women, and how very powerless they truly were, to a great extent. From an innocent little girl, to marriageable young ladies, to wives and even mother-in-laws. No one is safe; all are susceptible to mistreatment without recourse.

Dickens seems to be detailing the horrific abuses of women, and how very powerless they truly were, to a great extent. From an innocent little girl, to marriageable young ladies, to wives and even mother-in-laws. No one is safe; all are susceptible to mistreatment without recourse. By distancing us from the villain he can make the social "crimes" even more explicit. Perhaps that is why Quilp's character is so evil. Dickens can spotlight the atrocities without being offensive to the majority of men who would certainly never identify with the hideous, villainous dwarf.

I find very little moral ambiguity in Dickens, but this would be a way of writing about them, making his views quite plainly. Detailing the total oppression, subservience and physical abuse of females in The Old Curiosity Shop, he didn't let himself open to criticism, yet continued to have an effect on public opinion and legislation. And of course the supremely good female, "the child", quickly takes on the adult role.

I have just finished the book and need to ponder awhile now. I am so pleased that on his final tying up of ends Dickens told us what happened to the horse Whiskers. He was one of my favourite characters - so self-willed and also so canny!

I have just finished the book and need to ponder awhile now. I am so pleased that on his final tying up of ends Dickens told us what happened to the horse Whiskers. He was one of my favourite characters - so self-willed and also so canny!I was particularly gripped near the final chapters by (view spoiler)

And I now think Oscar Wilde's comment about the ending of The Old Curiosity Shop was just done for cleverness. Very witty, but not very fair!

What I always say about Dickens is he makes you laugh, he makes you cry...

What I always say about Dickens is he makes you laugh, he makes you cry...Oh here's a pointed remark - a little dig at us all, voiced by Sampson Brass but really a long-standing irritation of Dickens, who always wanted to be ultra-respectable,

"I am styled "gentleman"... I am not one of your players of music, stage actors, writers of books, or painters of pictures, who assume a station that the laws of their country don't recognise. I am none of your strollers or vagabonds."

Of course Dickens was both a stage actor and a writer - doubly damned ;)

Real-life Locations:

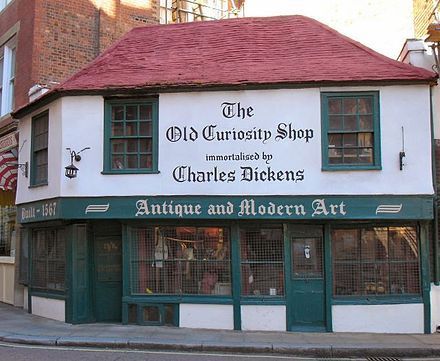

Real-life Locations:1. This building on Portsmouth Street, Holborn, London

seems to have been the inspiration for the shop of the title. It was built in 1567, and Dickens used to frequent it. After The Old Curiosity Shop was published, the building was named in its honour.

2. St Bartholomew's Church in Tong, Shropshire

is supposed to be where the grave of Little Nell was situated. Hang on, you say, she was fictitious! Well exactly...

The serialisation of The Old Curiosity Shop was hugely successful in the USA, and with the last installment, people crowded on the pier in New York demanding to know the ending (view spoiler) Afterwards, Americans started to come over to visit various sites in the novel. Dickens had visited Tong church when his grandmother worked at Tong castle, and it was possible to identify it from various references in the novel. Once the visitors came a money-spinning plot was hatched...

The local verger forged an entry in the church register of burials, the local people paid for a headstone, and the American tourists were thus duped into paying to see the supposed grave.

With apologies to all you USA readers :D

3. Other identifiable locations are:

Aylesbury, Bucks the churchyard where Nell and her Grandfather meet Codlin and Short

Banbury, Oxon the horse races where Nell and her Grandfather go with the show people

Warmington, Warwicks where the schoolmaster lives

Gaydon, Warwicks where they originally meet Mrs Jarley

Warwick the town where her waxworks are based

Birmingham, of course, the heavily industrialised town where the furnaces are

Wolverhampton, in the Black Country where Nell (view spoiler)

Dickens lived very near The Old Curiosity Shop which is why he visited it so often, and his grandmother lived in Tong. Not absolutely sure when he saw the others... he walked for miles and miles of course, but they do seem a little far!

(The Nicholas Nickleby research, on the other hand, was all done secretly in Yorkshire, with Hablot Browne, both in cognito.)

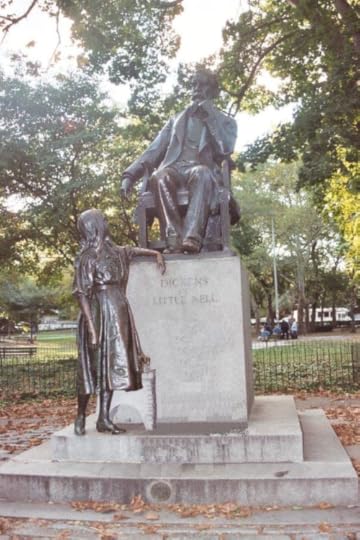

Here's the statue of Charles Dickens and "Little Nell" in Phildelphia, dating from 1890

Here's the statue of Charles Dickens and "Little Nell" in Phildelphia, dating from 1890

Originally it was commissioned by the founder of the "Washington Post" to be placed in London, but did not get approval, because any statue of him was expressly against Dickens's wishes.

His will had forbidden "any monument, memorial or testimonial, whatever. I rest my claims to remembrance on my published works and to the remembrance of my friends upon their experiences of me."

There was only one other statue of Charles Dickens in the world until the one which was placed in Portsmouth, England in February of this year! Amid much controversy, as you might expect.

Another interesting titbit, the Small Servant aka "the Marchioness" aka Sophronia Sphynx. Why is she so illtreated by Sally Brass? It turns out that Dickens made their relationship far more explicit in his original version.

Another interesting titbit, the Small Servant aka "the Marchioness" aka Sophronia Sphynx. Why is she so illtreated by Sally Brass? It turns out that Dickens made their relationship far more explicit in his original version.(view spoiler)

I found the middle part pretty grim. But chapter 38 contains one of my favourite paragraphs - the true heart of Dickens:

I found the middle part pretty grim. But chapter 38 contains one of my favourite paragraphs - the true heart of Dickens:"Oh! if those who rule the destinies of nations would but remember this - if they would but think how hard it is for the very poor to have engendered in their hearts, that love of home from which all domestic virtues spring, when they live in dense and squalid masses where social decency is lost, or rather never found - if they would but turn aside from the wide thoroughfares and great houses, and strive to improve the wretched dwellings in bye-ways where only Poverty may walk - many low roofs would point more truly to the sky, than the loftiest steeple that now rears proudly up from the midst of guilt, and crime, and horrible disease, to mock them by its contrast. In hollow voices from Workhouse, Hospital, and jail, this truth is preached from day to day, and has been proclaimed for years."

In fact I love this so much that I'll extract a little bit and upload it to add to the "Goodreads Old Curiosity Shop quotes" bank right now.

About Sally Brass... The fact that Charles Dickens altered his manuscript of The Old Curiosity Shop before publishing it in novel form, does imply that he had second thoughts about "the Marchioness" I think. The backstory I mentioned, which he originally wrote for her, didn't really ring true with anything else in the book, so was probably just a loose end, that he might or might not have developed later on. When he found that he hadn't, and the serial was over, he just eliminated it.

About Sally Brass... The fact that Charles Dickens altered his manuscript of The Old Curiosity Shop before publishing it in novel form, does imply that he had second thoughts about "the Marchioness" I think. The backstory I mentioned, which he originally wrote for her, didn't really ring true with anything else in the book, so was probably just a loose end, that he might or might not have developed later on. When he found that he hadn't, and the serial was over, he just eliminated it. He must have been keen to make many changes - if he'd only had the time, I should think! He didn't bother with the first three chapters, for instance. That seems the most likely interpretation of events. And then of course any theory as to (view spoiler) would still hold.

I expected to dislike this one, having remembered it as sentimental, but in fact I found far more to enjoy - the characterisation in particular. I think the characters were a little exaggerated perhaps, but to me that was part of its fairytale charm. No way would I say this novel is without faults! It does split opinion with modern audiences, and probably depends a lot on how much you are willing to forgive Dickens his extravagances and bluster in order to enjoy his quirks and wit!

Two main reasons that I forgive him:

1. It was serial fiction, with all the "quick fixes" that implies. We don't really expect our soap characters to hold up to close analysis.

2. He wrote so much, so fast. When I consider whether I would have preferred him to edit in a less slapdash way, I wonder if this would be at the expense of half his output. Would I lose one novel, to gain a slightly better other novel? And the answer for me is "No!" Jane Austen, a lot earlier, edited over and over again, apparently. Her novels are razor-sharp and superb. But there are only six that are any good.

As I say, I think this is a matter of preference, rather than a "right or wrong" issue. My favourite Dickens novels are the middle ones, but they do lose some of the wonderful humour (as far as I remember!!)

The public knew all about Mary Hogarth. They all lived together after all. But it's unlikely they knew to what extent Dickens was obsessed by her. He always presented himself as the archetypal respectable husband. He even justified himself years later, after Catherine had borne him 10 children, when he ordered a carpenter to build a barrier between their two parts of the bedroom. A little later Catherine was denied access to all but one of their children, just on Dickens's whim. The public forgave him an awful lot. Times were very different...

Is there a "right way" to read the novels of Charles Dickens? I don't think so! I do understand and empathise with both the people who rush through a novel - and also those who take it dead slow.

Is there a "right way" to read the novels of Charles Dickens? I don't think so! I do understand and empathise with both the people who rush through a novel - and also those who take it dead slow. In real life, never mind reading, I've frequently been told not to "overanalyse" things, but it's in my nature. I hate the feeling that there's something there but I'm not understanding it. Never have been one to let things "wash over" me. (This saying has gone down in family history, as the defence of one particular head teacher, when I suggested that the children in her school were running riot. Shouldn't she take it in hand? But that was her disgraceful reply. I did not apply for the job...) And I know there are some readers who hate my analytical reviews, for instance, because it can spoil a novel for them to "pick it to pieces".

And I too like to sit back and admire the "verve and gusto" of Dickens. So it's all a matter of degree, and mood, because one of the most enjoyable things about Goodreads is that it's not formal study! We can read what we want, when we want and how we want! Nobody to breathe down our necks :)

Maybe it's a question of age and experience? As we get older we can approach reading however we like. We do not have to do anything except have a gut reaction to our reading, but if we want to, we can analyse it to death. Plenty of critics do this with Dickens, and I suppose I do if something takes my fancy. I just don't expect there to be any "right answers".

A lot of the time his writing was so heavily influenced by his life, his beliefs, his personality and his hang-ups. Maybe more than some other writers, because he didn't iron it out. The reason I compared him with Jane Austen was because they are such polar opposites in this way!

I think her novels are especially appealing classics for young girls, who tend to identify with the heroines. Then their additional depth becomes more apparent to experienced readers of both sexes. Chris (my husband) told me once that his English master at Grammar school said to him, "If you don't like Jane Austen, then read her when you get older." I think that was sound advice ;)

Everything we read seems to tell us that Dickens was regarded with awe - rather like the Beatles in their heyday. And of course Queen Victoria liked The Old Curiosity Shop and loved the portrayal of Little Nell. Unfortunatle now he seems to have quite a lot in common with Quilp's behaviour. I'm not sure I can really see the resemblance to Dickens in this illustration of Quilp though...

Everything we read seems to tell us that Dickens was regarded with awe - rather like the Beatles in their heyday. And of course Queen Victoria liked The Old Curiosity Shop and loved the portrayal of Little Nell. Unfortunatle now he seems to have quite a lot in common with Quilp's behaviour. I'm not sure I can really see the resemblance to Dickens in this illustration of Quilp though...

Grip was based on a pet raven Dickens had, called Grip. It wasn't his first, but it was the one he loved most. And this raven died in 1841, from eating lead chips. Dickens had it stuffed, copying George IV who had had his pet giraffe stuffed.

Grip was based on a pet raven Dickens had, called Grip. It wasn't his first, but it was the one he loved most. And this raven died in 1841, from eating lead chips. Dickens had it stuffed, copying George IV who had had his pet giraffe stuffed.And Edgar Allan Poe's poem The Raven was inspired by Grip ... Russell Lowell, who was a contemporary of Poe's, rather unkindly wrote,

"Here comes Poe with his Raven, like Barnaby Rudge,

Three fifths of him genius, two fifths sheer fudge."

The original engravings in this book are by two of Dickens's favourite artists, George Cattermole and Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). Here's Cattermole's very first illustration of "The Maypole" public house, where a lot of the action will be set:

The original engravings in this book are by two of Dickens's favourite artists, George Cattermole and Hablot K. Browne ("Phiz"). Here's Cattermole's very first illustration of "The Maypole" public house, where a lot of the action will be set:

And here's some of Dickens's description of it. He often makes his buildings sound like actual people :)

"The Maypole was an old building, with more gable ends than a man would care to count on a sunny day ... It was a hale and hearty age though, still: and in the summer or autumn evenings, when the glow of the setting sun fell upon the oak and chestnut trees of the adjacent forest, the old house, partaking of its lustre, seemed their fit companion, and to have many good years of life in him yet."

Now I particularly love this picture, because it's a real place, a few minutes' drive from where I live! In Dickens's day the road was not a very easy one to travel and inhabited by highwaymen - but the building is still there. It's not the one called "The Maypole" - they pinched the name - but the original pub is this one:

And this is what Dickens wrote about it to his mentor, friend, and later, biographer John Forster,

“Chigwell, my dear fellow, is the greatest place in the world. Name your day for going. Such a delicious old inn facing the church–such a lovely ride–such forest scenery–such an out-of-the-way rural place–such a sexton! I say again, Name your day.”

Although it was built in 1547, and is one of the oldest public houses in England, "Ye Olde Kings Head" has actually been an upmarket Turkish restaurant since 2011! :D

I'm really enjoying it right from the start! There's such an air of mystery with the two strangers in the Maypole, that long involved story of murder and intrigue told by old Solomon Daisy, envigorating horserides in the pitch black across the treacherous highwayman-infested wilds of Essex, the young gentleman set upon in the dark by ... unknown foes, two claimants on Dolly's affections, and the feeling of unease and change - the brewing of the riots, just under the surface. Derring deeds afoot! And I've only read 5 chapters.

I'm really enjoying it right from the start! There's such an air of mystery with the two strangers in the Maypole, that long involved story of murder and intrigue told by old Solomon Daisy, envigorating horserides in the pitch black across the treacherous highwayman-infested wilds of Essex, the young gentleman set upon in the dark by ... unknown foes, two claimants on Dolly's affections, and the feeling of unease and change - the brewing of the riots, just under the surface. Derring deeds afoot! And I've only read 5 chapters.All the Maypole scenes are steeped in atmosphere. I have the feeling of being sat right there with the characters, on a cold, dark winter's evening, enjoying a glass of punch, listening to the crackle of the fire, and watching the smoke curling upwards from one of those long-stemmed pipes ...

I'm noticing far more "cliffhangers" than before in his novels. Barnaby Rudge was originally published in 88 weekly installments in Master Humphrey's Clock, between Feb and Nov 1841. So although it's a longish novel, it has a short gap between each episode compared with, say the previous one Nicholas Nickleby, which was in 19 monthly installments.

I'm noticing far more "cliffhangers" than before in his novels. Barnaby Rudge was originally published in 88 weekly installments in Master Humphrey's Clock, between Feb and Nov 1841. So although it's a longish novel, it has a short gap between each episode compared with, say the previous one Nicholas Nickleby, which was in 19 monthly installments.Take the thrilling end of chapter 20,

"She was really frightened now, and was yet hesitating what to do, when the bushes crackled and snapped, and a man came plunging through them, close before her."

So readers at the time would have to wait until the next episode to find out that it is (view spoiler).

Or the one I've just read, chapter 30, where (view spoiler),

"I have done it now ... I knew it would come at last. The Maypole and I must part company. I'm a vagabond - she hates me for evermore - it's all over!"

Dickens certainly knew how to keep his audience in suspense! We of course can just turn the page, or swipe the ereader, but they must have found it unbearably frustrating. There's an anecdote about this, which is probably apocryphal ...

"One day a lady was at a Smiths bookseller at a train station and asked the vendor for the next installment of the most recent Dickens novel. The vendor said that he had not received them yet. She persisted and said he should have it in stock by now. The lady became irritated on the station platform.

A rather short, well-dressed man approached her and said,

"Excuse me. My name is Charles Dickens and I have not yet even begun the next installment. It is not due until next week."

I'm enjoying rereading this book far more than I expected to - there are just so many things going on. Dickens is clearly viewing this as a serious novel; it gives the impression of being carefully planned out in his mind. This means it doesn't wander as much and he can create all the tension and atmosphere - far more than in any of his other novels up to this point. So much moody menace - it's wonderful!

I'm enjoying rereading this book far more than I expected to - there are just so many things going on. Dickens is clearly viewing this as a serious novel; it gives the impression of being carefully planned out in his mind. This means it doesn't wander as much and he can create all the tension and atmosphere - far more than in any of his other novels up to this point. So much moody menace - it's wonderful! Yet he still is essentially Dickens. Within all that darkness he'll sometimes pop a quirky character, or a droll episode, the description of which makes me laugh out loud. It's still very episodic although there's more direction.

I did find Dolly tiresome at the beginning, but very funny from the beginning. Parts like these,

"Dolly's eyes, by one of those strange accidents for which there is no accounting, wandered to the glass again"

"To make one's sweetheart miserable is well enough and quite right, but to be made miserable one's self is a little too much!"

show a keen eye for the vanity of youth by Dickens. One feels he is somehow in love with his coquettish character yet if she existed in real life she'd be unbearable!

She's improving a little now though, and we see an inner astuteness coming out, when she remarks of the manipulative smooth-talker (view spoiler),

"I'm pretty sure he was making game of us, more than once."

I didn't expect such a little cutie to be quite so acute.

from chapter 33 "One wintry evening, early in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty, a keen north wind arose as it grew dark, and night came on with black and dismal looks. A bitter storm of sleet, sharp, dense, and icy-cold, swept the wet streets, and rattled on the trembling windows."

from chapter 33 "One wintry evening, early in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and eighty, a keen north wind arose as it grew dark, and night came on with black and dismal looks. A bitter storm of sleet, sharp, dense, and icy-cold, swept the wet streets, and rattled on the trembling windows."could describe today in the same location too!

I'm really quite taken with the idea that I'm only a couple of miles down the road from these events, and although it's set well over 200 years ago, some things are the same ...

I am loving Barnaby Rudge! I can remember having previously said (maybe a year ago?) that I didn't feel historical novels were Dickens's forte - well I now wish I could take that back as the descriptions of the riots are so powerful and intense. Yet his quirky humour is present too, in all the eccentric characters and environments. I know of no other author who can do this quite so well. This is my second reading of the novel (first was audio) and I am savouring every word.

I am loving Barnaby Rudge! I can remember having previously said (maybe a year ago?) that I didn't feel historical novels were Dickens's forte - well I now wish I could take that back as the descriptions of the riots are so powerful and intense. Yet his quirky humour is present too, in all the eccentric characters and environments. I know of no other author who can do this quite so well. This is my second reading of the novel (first was audio) and I am savouring every word.There's a definite switch in the second part - it's far more savage, and now I realise Charles Dickens's inspired choice of a simple-minded man for his focus character - it points up the ridiculousness of both the warring factions - ie the situation itself. Not only has Lord George Gordon (who is in this story presented as a deranged leader of the rioters) been sadly misinformed by his henchmen, but just in case you missed that, we have what Dickens calls a "natural" at the head of the riots, and standing guard over the treasure, ready to carry the can for all misdemeanours. And Grip of course provides a perfect foil - someone for him to pour his heart out to - all his steadfastness and determination - all his hopes of making his mother proud of him. Now he and Grip are both in (view spoiler), and I want to weep for the deliberate manipulation and contrived destruction of such innocent joy in life.

Charles Dickens's original title for this novel was "Gabriel Varden - The Locksmith of London", but by altering the title itself - even if he did not include any more episodes about Barnaby - he has made his readers focus more on Barnaby Rudge. Just brilliant!

It's been said that some passages are similar to those of Victor Hugo, whom I have not yet read. Charles Dickens only ever wrote two historical novels - this one and A Tale of Two Cities - which was much later. And by then he'd learnt his lesson, and did a lot of prior research, spending a lot of time with Thomas Carlyle discussing the French Revolution as well as borrowing many of Carlyle's books on the subject. This was because Barnaby Rudge had been criticised for having some details wrong. For example two of the characters in this one - Lord Gordon and Gashford - talk of the Catholic Relief Bill as though it was still under discussion, but it had already been passed as a law 2 years earlier in 1778, and the Gordon Riots were in fact a reaction to it.

It's been said that some passages are similar to those of Victor Hugo, whom I have not yet read. Charles Dickens only ever wrote two historical novels - this one and A Tale of Two Cities - which was much later. And by then he'd learnt his lesson, and did a lot of prior research, spending a lot of time with Thomas Carlyle discussing the French Revolution as well as borrowing many of Carlyle's books on the subject. This was because Barnaby Rudge had been criticised for having some details wrong. For example two of the characters in this one - Lord Gordon and Gashford - talk of the Catholic Relief Bill as though it was still under discussion, but it had already been passed as a law 2 years earlier in 1778, and the Gordon Riots were in fact a reaction to it. That's not his real focus of interest though, nor mine! And the broad outline is correct. Individual characters spring to life, their idiosyncracies, vagaries and (in this novel) manipulative behaviour - what makes them tick - it's all there. The descriptions of mob mentality are spot-on - very detailed, grim and chilling. He really makes you see what is happening in your mind's eye:

"Covered with soot, and dirt, and dust, and lime; their garments torn to rags; their hair hanging wildly about them; their hands and faces jagged and bleeding with the wounds of rusty nails; Barnaby, Hugh, and Dennis hurried on before them all, like hideous madmen. After them, the dense throng came fighting on: some singing; some shouting in triumph; some quarrelling among themselves; some menacing the spectators as they passed; some with great wooden fragments, on which they spent their rage as if they had been alive, rending them limb from limb, and hurling the scattered morsels high into the air; some in a drunken state, unconscious of the hurts they had received from falling bricks, and stones, and beams; one borne upon a shutter, in the very midst, covered with a dingy cloth, a senseless, ghastly heap. Thus — a vision of coarse faces, with here and there a blot of flaring, smoky light; a dream of demon heads and savage eyes, and sticks and iron bars uplifted in the air, and whirled about; a bewildering horror, in which so much was seen, and yet so little, which seemed so long, and yet so short, in which there were so many phantoms, not to be forgotten all through life, and yet so many things that could not be observed in one distracting glimpse — it flitted onward, and was gone."

A glimpse straight from Dickens's imagination shooting into ours. I could choose many descriptions, but these next bits have a truly nightmarish quality for me:

"The more the fire crackled and raged, the wilder and more cruel the men grew; as though moving in that element they became fiends, and changed their earthly nature for the qualities that give delight in hell...

On the skull of one drunken lad — not twenty, by his looks — who lay upon the ground with a bottle to his mouth, the lead from the roof came streaming down in a shower of liquid fire, white hot; melting his head like wax. When the scattered parties were collected, men — living yet, but singed as with hot irons — were plucked out of the cellars, and carried off upon the shoulders of others, who strove to wake them as they went along, with ribald jokes, and left them, dead, in the passages of hospitals. But of all the howling throng not one learnt mercy from, or sickened at, these sights; nor was the fierce, besotted, senseless rage of one man glutted."

With this book being set in the small area where I'm living, everything seems to be more immediate. Things have moved on, and it just seems a very ordinary sort of place. Comment 638 shows what "The Maypole Inn", where a lot of it was set, looks like now. But the weather is the same! And people don't change much, just adapt to the mores of the society they're living in.

With this book being set in the small area where I'm living, everything seems to be more immediate. Things have moved on, and it just seems a very ordinary sort of place. Comment 638 shows what "The Maypole Inn", where a lot of it was set, looks like now. But the weather is the same! And people don't change much, just adapt to the mores of the society they're living in.So when I think that just over 200 years ago this was a wild area at the mercy of desperate highwaymen, and those riots although maybe not correct in every detail did really happen, and the descriptions are of actual events, it seems very close to home. The horror feels very real. Whereas if I read a novel by Steven King, its a different sort of horror and not as intense. He once said, if he couldn't scare people then he tried to disgust them. Charles Dickens's descriptions of mob behaviour in Barnaby Rudge may not be gross as King's, but they are every bit as explicit in places, hair-raising and horrific.

On the other hand, Dickens is a dab hand at discursiveness, and just when I think I can't take any more of this he has me laughing out loud with some ridiculous episode, description of an eccentric character - or just an observation in passing such as this:

“"It’s as plain", returned Solomon, "as the nose on Parkes’s face" – Mr Parkes, who had a large nose, rubbed it, and looked as if he considered this a personal allusion.”

I think he knows people inside out, although to a certain extent he is constrained by the times he lives in, as are we all. We have more opportunities than ever now to look at different ways of seeing the world, but sadly not all people open up their minds.

This is a quotation from chapter 68, which is incredibly graphic and horrible. I do not want to lose it,

This is a quotation from chapter 68, which is incredibly graphic and horrible. I do not want to lose it,"But there was a worse spectacle than this - worse by far than fire and smoke, or even the rabble's unappeasable and maniac rage. The gutters of the street, and every crack and fissure in the stones, ran with scorching spirit, which being dammed up by busy hands, overflowed the road and pavement, and formed a great pool, into which the people dropped down dead by dozens. They lay in heaps all round this fearful pond, husbands and wives, fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, women with children in their arms and babies at their breasts, and drank until they died. While some stooped with their lips to the brink and never raised their heads again, others sprang up from their fiery draught, and danced, half in a mad triumph, and half in the agony of suffocation, until they fell, and steeped their corpses in the liquor that had killed them. Nor was even this the worst or most appalling kind of death that happened on this fatal night. From the burning cellars, where they drank out of hats, pails, buckets, tubs, and shoes, some men were drawn, alive, but all alight from head to foot; who, in their unendurable anguish and suffering, making for anything that had the look of water, rolled, hissing, in this hideous lake, and splashed up liquid fire which lapped in all it met with as it ran along the surface, and neither spared the living nor the dead."

MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT:

MARTIN CHUZZLEWIT:Complete list of publication dates:

I – January 1843 (chapters 1–3)

II – February 1843 (chapters 4–5)

III – March 1843 (chapters 6–8)

IV – April 1843 (chapters 9–10)

V – May 1843 (chapters 11–12)

VI – June 1843 (chapters 13–15)

VII – July 1843 (chapters 16–17)

VIII – August 1843 (chapters 18–20)

IX – September 1843 (chapters 21–23)

X – October 1843 (chapters 24–26)

XI – November 1843 (chapters 27–29)

XII – December 1843 (chapters 30–32)

XIII – January 1844 (chapters 33–35)

XIV – February 1844 (chapters 36–38)

XV – March 1844 (chapters 39–41)

XVI – April 1844 (chapters 42–44)

XVII – May 1844 (chapters 45–47)

XVIII – June 1844 (chapters 48–50)

XIX-XX – July 1844 (chapters 51–54)

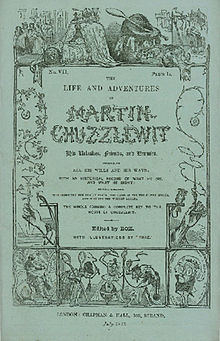

The original title for Martin Chuzzlewit was:

The original title for Martin Chuzzlewit was:"The

Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

His relatives, friends, and enemies.

Comprising all

His Wills and His Ways,

With an Historical record of what he did

and what he didn't;

Shewing moreover who inherited the Family Plate,

who came in for the Silver spoons,

and who for the Wooden Ladles.

The whole forming a complete key

to the House of Chuzzlewit."

By the time it was published in book form it was simply called "The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit"

Some of the chapter titles are equally long. Chapter 4's title takes up a whole page on my kindle!

I assume the titles for each serial number were the same as these in the book form, since the tendency was to shorten things when published as a book, but can't be sure. Maybe to whet the appetite?

I assume the titles for each serial number were the same as these in the book form, since the tendency was to shorten things when published as a book, but can't be sure. Maybe to whet the appetite?I laughed out loud at his sarcastic comments regarding the ancient family of Chuzzlewit. Then loved all the personification at the beginning of chapter 2. All the elements of Nature being so cheery and optimistic just for a moment, but then,

"The sun went down beneath the long dark lines of hill and cloud which piled up in the west an airy city, wall heaped on wall, and battlement on battlement; the light was all withdrawn; the shining church turned cold and dark; the stream forgot to smile; the birds were silent; and the gloom of winter dwelt on everything."

I feel almost sure this must be foreshadowing the feel and tone of the novel to come, and all the dark elements we are to expect. Oh - and I love the introduction we get to that oily Mr Pecksniff, where the impish wind knocks him over making him look ridiculous :D

The oily hypocrite

Mr Pecksniff

was based on a real person, Samuel Carter Hall. Samuel Carter Hall was an Irish-born Victorian journalist who edited "The Art Journal" and was widely satirised. He made Old Masters (such as Raphael or Titian's paintings) virtually unsaleable, by exposing the profits that custom-houses were earning by importing them. By doing this, he hoped to support modern British art by promoting young artists and attacking the market for unreliable Old Masters. However, he was deeply unsympathetic to the Pre-Raphaelites, and published several attacks upon the movement. Here's a description of him by Julian Hawthorne,

The oily hypocrite

Mr Pecksniff

was based on a real person, Samuel Carter Hall. Samuel Carter Hall was an Irish-born Victorian journalist who edited "The Art Journal" and was widely satirised. He made Old Masters (such as Raphael or Titian's paintings) virtually unsaleable, by exposing the profits that custom-houses were earning by importing them. By doing this, he hoped to support modern British art by promoting young artists and attacking the market for unreliable Old Masters. However, he was deeply unsympathetic to the Pre-Raphaelites, and published several attacks upon the movement. Here's a description of him by Julian Hawthorne,"Hall was a genuine comedy figure. Such oily and voluble sanctimoniousness needed no modification to be fitted to appear before the footlights in satirical drama. He might be called an ingenuous hypocrite, an artless humbug, a veracious liar, so obviously were the traits indicated innate and organic in him rather than acquired ... His indecency and falsehood were in his soul, but not in his consciousness; so that he paraded them at the very moment that he was claiming for himself all that was their opposite."

And here are some quotes about Mr Pecksniff which delighted me :)

"When I say we, my dear ... I mean mankind in general; the human race, considered as a body, and not as individuals. There is nothing personal in morality, my love."

So as he gives his daughters Charity and Mercy a lecture, he sermonises using abstract principles, thus cleverly distancing himself from any moral responsibility!

And here, he's doing what he's so expert at - sanctimoniously pretending he's providing for others, whilst in actuality making sure of his own comfort. This seems to me to be a direct comparison with the observation made of Samuel Carter Hall,

"And how,' asked Mr Pecksniff, drawing off his gloves and warming his hands before the fire, as benevolently as if they were somebody else's, not his; 'and how is he now?"

"Who is with him now,' ruminated Mr Pecksniff, warming his back (as he had warmed his hands) as if it were a widow's back, or an orphan's back, or an enemy's back, or a back that any less excellent man would have suffered to be cold. 'Oh dear me, dear me!"

The beginning of this one is so very funny and full of joie de vivre! It's always such a relief to be reading Dickens again!

The beginning of this one is so very funny and full of joie de vivre! It's always such a relief to be reading Dickens again!Yet I've just been reading about Charles Dickens's precarious situation when he started writing Martin Chuzzlewit. He was 30 when he started writing the novel, and given his responsibilities, I don't know how he could write with such a light touch. Apparently the sales were much lower than expected, and it was a worrying time for him. He'd borrowed money to finance his American trip the year before (1842), and he and Kate were expecting child number 5.

It's apparently also the first novel which he planned in advance, and he had his hero Martin go off to America, in the sixth installment, to try to stimulate a bit more interest.

This is really surprising to me, as it's easily among the funniest and most smoothly written so far! I wonder what it was that his readers were wanting, and that they found lacking.

Back to read a bit more. I can't keep away from these wonderful characters - and those names Montague Tigg, Chevy Slyme, Mr and Mrs Spottletoe, Tom Pinch, Charity and Mercy (Cherry and Merry) Pecksniff ...

I'm really enjoying the passages about Montague Tigg and Chevy Slyme (what wonderful names!) Here's Montague Tigg pontificating,

I'm really enjoying the passages about Montague Tigg and Chevy Slyme (what wonderful names!) Here's Montague Tigg pontificating,"I understand your mistake, and I am not offended. Why? Because it's complimentary. You suppose I would set myself up for Chevy Slyme. Sir, if there is a man on earth whom a gentleman would feel proud and honoured to be mistaken for, that man is my friend Slyme. For he is, without an exception, the highest-minded, the most independent-spirited, most original, spiritual, classical, talented, the most thoroughly Shakspearian, if not Miltonic, and at the same time the most disgustingly-unappreciated dog I know. But, sir, I have not the vanity to attempt to pass for Slyme. Any other man in the wide world, I am equal to; but Slyme is, I frankly confess, a great many cuts above me. Therefore you are wrong."

It's not at all clear why Tigg, such a shabby mockery of a gentleman is feigning such admiration for his companion, Slyme, a drunk, self-important and self-loathing, embittered man.

When Mark Tapley describes Tigg, he says,

"And I think Mrs Lupin lets him and his friend off very easy in not charging 'em double prices for being a disgrace to the Dragon. That's my opinion. I wouldn't have any such Peter the Wild Boy as him in my house, sir, not if I was paid race-week prices for it."

Here's a bit about Peter the Wild Boy:

"Peter the Wild Boy was a mentally handicapped boy from Hanover in northern Germany who was found in 1725 living wild in the woods near Hamelin, the town of Pied Piper legend. The boy, of unknown parentage, had been living an entirely feral existence for an unknown length of time, surviving by eating forest grass and leaves; he walked on all fours, exhibited uncivilized behaviour and could not be taught to speak a language. Peter was found in the Hertswold Forest by a party of hunters led by George I while on a visit to his Hanover homeland and brought to Great Britain in 1726. He is now believed to have suffered from the very rare genetic disorder Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome... Jean-Jacques Rousseau called Peter ‘the noble savage’, man ‘unspoilt’ by society and civilisation. Daniel Defoe addressed the subject in his pamphlet 'Mere Nature Delineated', published in 1726. He described Peter as an ‘object of pity’ but cast doubt on the story of his origins, dismissing it as a ‘Fib’"

There's a lot of subtlety in the relationship between Monatague Tigg and Chevy Slyme.

There's a lot of subtlety in the relationship between Monatague Tigg and Chevy Slyme.Sometimes Dickens is clearly referring to stories or people who were well known at the time, and now more or less forgotten. It's easy to miss even the fact that it's a reference!

When one of the characters mistakenly suggests "oysters" instead of sirens or mermaids it's just funny, but sometimes the jokes pass by without being noticed, I think. Such as this, when Mr. Pecksniff assures Martin Chuzzlewit and Tom Pinch,

"There is no mystery; all is free and open. Unlike the young man in the Eastern tale - who is described as a one-eyed almanac, if I am not mistaken, Mr Pinch? -'

'A one-eyed calender, I think, sir,' faltered Tom."

Apparently there's a meaning of "calender" which I didn't know, that of meaning "a dancing dervish who begs". So perhaps Pecksniff has not only mistaken the word "almanac" for this meaning of "calendar", but also presumably chosen the grander word of the two in keeping with his self-aggrandisement. So so many levels it's possible to probe ...

Ho ho! The words "Pecksniffian" and Pecksniffery" are in the dictionary! He's certainly one of the most odious characters I've come across yet in Dickens.

Ho ho! The words "Pecksniffian" and Pecksniffery" are in the dictionary! He's certainly one of the most odious characters I've come across yet in Dickens. "Sanctimonious, officious, hypocritical, pretentious and condescending, affecting high moral standards, hypocritically benevolent."

Similar to (the as yet uncreated) Uriah Heep?

Maybe Pecksniff was festering along nicely in the back of his mind all through Dombey and Son, and then reached new depths of obsequiousness and depravity 5 years later, culminating in the Uriah Heap of David Copperfield.

I'm mulling over who the title actually refers to. The senior or the junior Martin. It sounds like the senior, and originally I think Dickens meant it to be so, as he had no idea how the novel was going to develop. John Forster notes,

I'm mulling over who the title actually refers to. The senior or the junior Martin. It sounds like the senior, and originally I think Dickens meant it to be so, as he had no idea how the novel was going to develop. John Forster notes,"Title and even story had been undetermined while we travelled" and "Beginning so hurriedly as at last he did, altering his course at the opening and seeing little as yet of the main track of his design,"

He even fiddled about with the main character's name, trying out Sweezleden, Sweezleback, Sweezlewag, Chuzzletoe, Chuzzleboy, Chubblewig, and Chuzzlewig

By the third number he'd decided it would be partly about "old Martin's plot to degrade and punish Pecksniff," but this was all writing on the hoof, as usual!

Who does the title refer to? It's quite a conundrum.

Who does the title refer to? It's quite a conundrum.I think we all assume it's the younger, because that's who the novel concentrates on, and who readers are ususally interested in, not the old codgers. Mainly it is about Martin junior's journey, his personal and moral development, just as Nicholas Nickleby was. But the complete title (in message 731) seems much more to refer to Martin senior. And John Forster (who was there at the time) says,

"All which latter portion of the title was of course dropped as the work became modified, in its progress, by changes at first not contemplated"

So it sounds to me as if Dickens himself changed his mind. Martin senior plays an important role in the novel anyway. He's a pivotal character in a way as it is his money which starts the whole thing off. And his temperament is irresistible - a really quirky so-and-so!

I'm just about to start chapter 18. I'm reserving judgement about the American scenes so far. Part of me think they're just too over-blown to be funny. I'm wondering if Dickens's anger at events such as copyright infringement is leading to him overstating his case. I have to admit I'm looking forward to the next chapter and getting back to the Chuzzlewits!

I'm just about to start chapter 18. I'm reserving judgement about the American scenes so far. Part of me think they're just too over-blown to be funny. I'm wondering if Dickens's anger at events such as copyright infringement is leading to him overstating his case. I have to admit I'm looking forward to the next chapter and getting back to the Chuzzlewits!

I like the titles of the American newspapers, The"Sewer", "Stabber", "Family Spy", "Private Listener", "Peeper" and so on.

I like the titles of the American newspapers, The"Sewer", "Stabber", "Family Spy", "Private Listener", "Peeper" and so on.And this is a very droll observation which could probably be applied to the citizens of various countries,

"'You have come to visit our country, sir, at a season of great commercial depression,' said the major.

'At an alarming crisis,' said the colonel.

'At a period of unprecedented stagnation,' said Mr Jefferson Brick.

'I am sorry to hear that,' returned Martin. 'It's not likely to last, I hope?'

Martin knew nothing about America, or he would have known perfectly well that if its individual citizens, to a man, are to be believed, it always IS depressed, and always IS stagnated, and always IS at an alarming crisis, and never was otherwise; though as a body they are ready to make oath upon the Evangelists at any hour of the day or night, that it is the most thriving and prosperous of all countries on the habitable globe."

But the depiction of Colonel Diver is so embittered. And the Norris family! What is their purpose? It seems to be solely so that Dickens can say how hypocritical all Americans are, and that even those who claim to be abolitionists are just as bigoted and racist as all the others.

He really seems to have it in for Americans. They have no table manners, they spit freely, they are coarse, bullies, blackmailers, out to defraud ... I am hoping that when we return we meet some more noble representatives! Yes, we had some very unpleasant greedy egotistical characters in the Chuzzlewit family, but it wasn't quite so unremitting. We also had Tom Pinch, his sister Ruth, Mary, Mark Tapley - in fact quite a few well-meaning characters now I think of it.

I usually really enjoy all his hyperbole. I'm just not sure the American part hits the spot for me just yet.

I usually really enjoy all his hyperbole. I'm just not sure the American part hits the spot for me just yet.But I think Dickens's heart was in the right place, and sometimes he managed to alter public opinion and in turn that sometimes fed into and influenced legal changes.

I'm just amazed that he could be so bitter and sarcastic when they had welcomed him with open arms and he was such a celebrity there! Is it that Dickens thought a tirade against Americans would be popular, because England had been at war with them within living memory? Maybe after all he was trying to appeal to recent grudges by the British population. There's an awful lot about how hypocritical he thinks the Americans are with their regard to Liberty and Independence.

I shouldn't be surprised at all the sarcasm, should I? Dickens was never one for half-measures, and I doubt whether he ever compromised on anything.

I've just met Mrs Gamp now. Ho ho ho!

I'm thinking Bleak House is still my favourite, at least it has been up to now. Who knows whether it still will be when I get there though! All these rereads have been an absolute delight :)

I'm thinking Bleak House is still my favourite, at least it has been up to now. Who knows whether it still will be when I get there though! All these rereads have been an absolute delight :)Or maybe Little Dorrit, which is also in my mind. Some don't like the split narration, with Little Dorrit being in two discrete parts, whereas with Bleak House Esther's narrative is interwoven.

I am looking forward to his greats, but enjoying the skill of these earlier one too. It strikes me that Martin Chuzzlewit is far more about character than story, but then the early part of Barnaby Rudge was also like that. You wonder when the story was going to begin, but thoroughly enjoy the incidentals. The descriptions of the various forms of greed, avarice and selfishness masquerading as benevolence are masterly.

A lot of people talk about Dickens's great stories, which is odd in a way, as I wouldn't have said it was his main thing!

It's difficult, this American issue. I think Dickens allowed his resentment against the copyright issue to cloud his judgement as to precisely how far he could go in order to make something or someone ridiculous. In these scenes so far he's strained my credibility. It's more as if he's on his soapbox, yet he usually does the satire so well.

It's difficult, this American issue. I think Dickens allowed his resentment against the copyright issue to cloud his judgement as to precisely how far he could go in order to make something or someone ridiculous. In these scenes so far he's strained my credibility. It's more as if he's on his soapbox, yet he usually does the satire so well. Still, they're just embarking on the voyage to Eden, so I have all that to come before I can judge properly for myself.

Books mentioned in this topic

Our Mutual Friend (other topics)Nicholas Nickleby (other topics)

The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (other topics)

Bleak House (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Charles Dickens (other topics)Anne Brontë (other topics)

Henry Mayhew (other topics)

Harland S. Nelson (other topics)

John Forster (other topics)

More...

We're getting some marvellously eccentric characters as well. I had thought that it was only in Nicholas Nickleby where he indulged his love for theatricals so much. But here, we've had a circus troupe... and now waxworks. And what a show! Mannequins who can double as different characters at the... drop of a hat? LOL! I particularly liked a Jasper Packlemerton who had 14 wives and destroyed them all by tickling the souls of their feet. An amazing feat of imagination by The Inimitable? Well...no, actually!

"A news item first published in the Illustrated Police News on December 11, 1869: "A Wife Driven Insane by Husband Tickling Her Feet." The account states that Michael Puckridge had previously threatened the life of his wife... Puckridge tricked his wife into allowing herself to be tied to a plank. Afterward, "Puckridge deliberately and persistently tickled the soles of her feet with a feather. For a long time he continued to operate upon his unhappy victim who was rendered frantic by the process. Eventually, she swooned, whereupon her husband released her. It soon became too manifest that the light of reason had fled. Mrs. Puckridge was taken to the workhouse where she was placed with the other insane inmates."

Extraordinary!