The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

Landslide

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES

>

PRESIDENTIAL SERIES: GLOSSARY -LANDSLIDE (SPOILER THREAD)

Queen Elizabeth II

Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; born 21 April 1926) is the constitutional monarch of 16 of the 53 member states in the Commonwealth of Nations. She is also Head of the Commonwealth and Supreme Governor of the Church of England.

Upon her accession on 6 February 1952, Elizabeth became Head of the Commonwealth and queen regnant of seven independent Commonwealth countries: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Pakistan and Ceylon. Her coronation the following year was the first to be televised. From 1956 to 1992, the number of her realms varied as territories gained independence and some realms became republics. Today, in addition to the first four of the aforementioned countries, Elizabeth is Queen of Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize, Antigua and Barbuda, and Saint Kitts and Nevis. She is the longest-lived and, after her great-great grandmother Queen Victoria, the second longest-reigning British monarch.

Elizabeth was born in London and educated privately at home. Her father acceded to the throne as George VI on the abdication of his brother Edward VIII in 1936, from which time she was the heir presumptive. She began to undertake public duties during the Second World War, in which she served in the Auxiliary Territorial Service. In 1947, she married Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, with whom she has four children: Charles, Anne, Andrew, and Edward.

Elizabeth's many historic visits and meetings include a state visit to the Republic of Ireland, the first state visit of an Irish president to the United Kingdom, and reciprocal visits to and from the Pope. She has seen major constitutional changes, such as devolution in the United Kingdom, Canadian patriation, and the decolonization of Africa. She has also reigned through various wars and conflicts involving many of her realms.

Times of personal significance have included the births and marriages of her children and grandchildren, the investiture of the Prince of Wales, and the celebration of milestones such as her Silver, Golden, and Diamond Jubilees in 1977, 2002, and 2012, respectively. Moments of sorrow for her include the death of her father, aged 56, the assassination of Prince Philip's uncle, Lord Mountbatten, the breakdown of her children's marriages in 1992 (a year deemed her annus horribilis), the death in 1997 of her son's former wife, Diana, Princess of Wales, and the deaths of her mother and sister in 2002. Elizabeth has occasionally faced republican sentiments and severe press criticism of the royal family, but support for the monarchy and her personal popularity remain high. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabet...)

More:

http://www.royal.gov.uk/hmthequeen/hm...

http://www.biography.com/people/queen...

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/people/q...

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/people/q...

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknew...

by Elizabeth Roberts (no photo)

by Elizabeth Roberts (no photo) by Susanna Davidson (no photo)

by Susanna Davidson (no photo) by Michael Paterson(no photo)

by Michael Paterson(no photo) by Andrew Marr (no photo)

by Andrew Marr (no photo) by

by

Cecil Beaton

Cecil Beaton by

by

Sally Bedell Smith

Sally Bedell Smith

message 303:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Dec 18, 2014 08:32AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Why the Cuba embargo needs to end, explained in 3 minutes

Updated by Zack Beauchamp on December 18, 2014, 9:30 a.m. ET

The US has started normalizing diplomacy with Cuba, but it will take an act of congress to end the embargo. Here are seven reasons why it should.

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/18/7414659...

Source: Vox

Article:

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/17/7408743...

Updated by Zack Beauchamp on December 18, 2014, 9:30 a.m. ET

The US has started normalizing diplomacy with Cuba, but it will take an act of congress to end the embargo. Here are seven reasons why it should.

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/18/7414659...

Source: Vox

Article:

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/17/7408743...

The End of the End of the Revolution

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/07/mag...

About the Author:

Roger Cohen, a columnist for The International Herald Tribune and The Times, is the author of “Hearts Grown Brutal: Sagas of Sarajevo.”

by Roger Cohen (no photo)

by Roger Cohen (no photo)

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/07/mag...

About the Author:

Roger Cohen, a columnist for The International Herald Tribune and The Times, is the author of “Hearts Grown Brutal: Sagas of Sarajevo.”

by Roger Cohen (no photo)

by Roger Cohen (no photo)

This powerful quote captures what life is like for Cubans under embargo

Cuban writer Yoani Sanchez speaking in Mexico

Jose Castanares/AFP/Getty

Author: Max Fisher

Article link below:

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/17/7412365...

But Yoani Sánchez, a Cuban dissident writer, articulated it heart-breakingly well, in a 2008 interview with New York Times columnist Roger Cohen. When Cohen asked her why the Cubans he saw sitting on Havana's seawall never seemed to look outward to the ocean, this is how she answered:

"We live turned away from the sea because it does not connect us, it encloses us. There is no movement on it. People are not allowed to buy boats because if they had boats, they would go to Florida. We are left, as one of our poets put it, with the unhappy circumstance of water at every turn."

Cuban writer Yoani Sanchez speaking in Mexico

Jose Castanares/AFP/Getty

Author: Max Fisher

Article link below:

http://www.vox.com/2014/12/17/7412365...

But Yoani Sánchez, a Cuban dissident writer, articulated it heart-breakingly well, in a 2008 interview with New York Times columnist Roger Cohen. When Cohen asked her why the Cubans he saw sitting on Havana's seawall never seemed to look outward to the ocean, this is how she answered:

"We live turned away from the sea because it does not connect us, it encloses us. There is no movement on it. People are not allowed to buy boats because if they had boats, they would go to Florida. We are left, as one of our poets put it, with the unhappy circumstance of water at every turn."

message 306:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

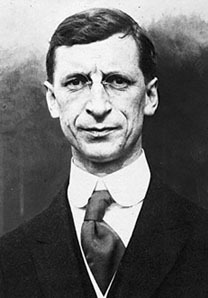

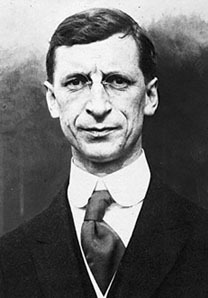

Éamon de Valera

Edward George de Valera was born on 14 October 1882 in New York to a Spanish father and an Irish mother. He moved to Ireland at the age of two and was brought up by relatives in Limerick. He became a teacher of mathematics and an avid supporter of the Irish language movement.

De Valera was a leader in the 1916 Easter Rising which proclaimed an Irish republic. Arrested, he was saved from a death sentence because of his American birth and instead received a prison term. On his release, he stood as a Sinn Fein Party candidate in the 1918 general election. Sinn Fein won the majority of seats outside Ulster, but refused to take their seats at Westminster, instead establishing an independent parliament (Dail Eireann) to govern Ireland. De Valera was elected president of the Dail.

The Irish Republican Army, the armed wing of Sinn Fein, began a guerrilla war against Crown forces. After two years of violence, a truce was agreed and a treaty with the British negotiated by a Sinn Fein deputation, which de Valera chose not to join. Michael Collins, who led the Sinn Fein negotiating party, described the result as 'the freedom to achieve freedom'. But de Valera opposed the agreement, because it involved the partition of Ireland and did not create an independent republic. The treaty was passed by a narrow margin in the Dail and de Valera resigned as president. He led the anti-treaty side in a bitter civil war against the government of the new Free State. Despite killing Collins, the irregulars were defeated.

De Valera reconciled himself to the new dispensation and led his party Fianna Fail into the Dail in 1927. Fianna Fail won elections in 1932. De Valera wrote a new constitution in 1937 asserting greater autonomy for Ireland, although stopping short of declaring the Free State a republic. This happened during a period in which he was in opposition in 1948. He was subsequently elected prime minister (taoiseach) three times and then president of the republic, a position he held until 1973. Under de Valera's rule, the cultural identity of the Irish Republic as Roman Catholic and Gaelic was asserted. Complete independence was secured, but a lasting accommodation with the majority Protestant and British Northern Ireland receded as a result. De Valera died on 29 August 1975.

(Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89am...

http://www.ireland-information.com/ar...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Eam...

http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/cocl...

http://www.ucd.ie/archives/html/colle...

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

http://www.biography.com/people/eamon...

http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/B...

http://www.winstonchurchill.org/suppo...

by Diarmaid Ferriter (no photo)

by Diarmaid Ferriter (no photo)

by Tim Pat Coogan (no photo)

by Tim Pat Coogan (no photo)

by T. Ryle Dwyer (no photo)

by T. Ryle Dwyer (no photo)

by Frank Pakenham Longford (no photo)

by Frank Pakenham Longford (no photo)

by Ryan Tubridy (no photo)

by Ryan Tubridy (no photo)

Edward George de Valera was born on 14 October 1882 in New York to a Spanish father and an Irish mother. He moved to Ireland at the age of two and was brought up by relatives in Limerick. He became a teacher of mathematics and an avid supporter of the Irish language movement.

De Valera was a leader in the 1916 Easter Rising which proclaimed an Irish republic. Arrested, he was saved from a death sentence because of his American birth and instead received a prison term. On his release, he stood as a Sinn Fein Party candidate in the 1918 general election. Sinn Fein won the majority of seats outside Ulster, but refused to take their seats at Westminster, instead establishing an independent parliament (Dail Eireann) to govern Ireland. De Valera was elected president of the Dail.

The Irish Republican Army, the armed wing of Sinn Fein, began a guerrilla war against Crown forces. After two years of violence, a truce was agreed and a treaty with the British negotiated by a Sinn Fein deputation, which de Valera chose not to join. Michael Collins, who led the Sinn Fein negotiating party, described the result as 'the freedom to achieve freedom'. But de Valera opposed the agreement, because it involved the partition of Ireland and did not create an independent republic. The treaty was passed by a narrow margin in the Dail and de Valera resigned as president. He led the anti-treaty side in a bitter civil war against the government of the new Free State. Despite killing Collins, the irregulars were defeated.

De Valera reconciled himself to the new dispensation and led his party Fianna Fail into the Dail in 1927. Fianna Fail won elections in 1932. De Valera wrote a new constitution in 1937 asserting greater autonomy for Ireland, although stopping short of declaring the Free State a republic. This happened during a period in which he was in opposition in 1948. He was subsequently elected prime minister (taoiseach) three times and then president of the republic, a position he held until 1973. Under de Valera's rule, the cultural identity of the Irish Republic as Roman Catholic and Gaelic was asserted. Complete independence was secured, but a lasting accommodation with the majority Protestant and British Northern Ireland receded as a result. De Valera died on 29 August 1975.

(Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89am...

http://www.ireland-information.com/ar...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Eam...

http://www.clarelibrary.ie/eolas/cocl...

http://www.ucd.ie/archives/html/colle...

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

http://www.biography.com/people/eamon...

http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/B...

http://www.winstonchurchill.org/suppo...

by Diarmaid Ferriter (no photo)

by Diarmaid Ferriter (no photo) by Tim Pat Coogan (no photo)

by Tim Pat Coogan (no photo) by T. Ryle Dwyer (no photo)

by T. Ryle Dwyer (no photo) by Frank Pakenham Longford (no photo)

by Frank Pakenham Longford (no photo) by Ryan Tubridy (no photo)

by Ryan Tubridy (no photo)

message 308:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I, original name Tafari Makonnen (born July 23, 1892, near Harer, Eth.—died Aug. 27, 1975, Addis Ababa), emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974 who sought to modernize his country and who steered it into the mainstream of post-World War II African politics. He brought Ethiopia into the League of Nations and the United Nations and made Addis Ababa the major centre for the Organization of African Unity (now African Union).

Tafari was a great-grandson of Sahle Selassie of Shewa (Shoa) and a son of Ras (Prince) Makonnen, a chief adviser to Emperor Menilek II. Educated at home by French missionaries, Tafari at an early age favourably impressed the emperor with his intellectual abilities and was promoted accordingly. As governor of Sidamo and then of Harer province, he followed progressive policies, seeking to break the feudal power of the local nobility by increasing the authority of the central government—for example, by developing a salaried civil service. He thereby came to represent politically progressive elements of the population. In 1911 he married Wayzaro Menen, a great-granddaughter of Menilek II.

When Menilek II died in 1913, his grandson Lij Yasu succeeded to the throne, but the latter’s unreliability and his close association with Islam made him unpopular with the majority Christian population of Ethiopia. Tafari became the rallying point of the Christian resistance, and he deposed Lij Yasu in 1916. Zauditu, Menilek II’s daughter, thereupon became empress in 1917, and Ras Tafari was named regent and heir apparent to the throne.

While Zauditu was conservative in outlook, Ras Tafari was progressive and became the focus of the aspirations of the modernist younger generation. In 1923 he had a conspicuous success in the admission of Ethiopia to the League of Nations. In the following year he visited Rome, Paris, and London, becoming the first Ethiopian ruler ever to go abroad. In 1928 he assumed the title of negus (“king”), and two years later, when Zauditu died, he was crowned emperor (Nov. 2, 1930) and took the name of Haile Selassie (“Might of the Trinity”). In 1931 he promulgated a new constitution, which strictly limited the powers of Parliament. From the late 1920s on, Haile Selassie in effect was the Ethiopian government, and, by establishing provincial schools, strengthening the police forces, and progressively outlawing feudal taxation, he sought to both help his people and increase the authority of the central government.

When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Haile Selassie led the resistance, but in May 1936 he was forced into exile. He appealed for help from the League of Nations in a memorable speech that he delivered to that body in Geneva on June 30, 1936. With the advent of World War II, he secured British assistance in forming an army of Ethiopian exiles in the Sudan. British and Ethiopian forces invaded Ethiopia in January 1941 and recaptured Addis Ababa several months later. Although he was reinstated as emperor, Haile Selassie had to recreate the authority he had previously exercised. He again implemented social, economic, and educational reforms in an attempt to modernize Ethiopian government and society on a slow and gradual basis.

The Ethiopian government continued to be largely the expression of Haile Selassie’s personal authority. In 1955 he granted a new constitution giving him as much power as the previous one. Overt opposition to his rule surfaced in December 1960, when a dissident wing of the army secured control of Addis Ababa and was dislodged only after a sharp engagement with loyalist elements.

Haile Selassie played a very important role in the establishment of the Organization of African Unity in 1963. His rule in Ethiopia continued until 1974, at which time famine, worsening unemployment, and the political stagnation of his government prompted segments of the army to mutiny. They deposed Haile Selassie and established a provisional military government that espoused Marxist ideologies. Haile Selassie was kept under house arrest in his own palace, where he spent the remainder of his life. Official sources at the time attributed his death to natural causes, but evidence later emerged suggesting that he had been strangled on the orders of the military government.

Haile Selassie was regarded as the messiah of the African race by the Rastafarian movement.

(Source:http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...)

More:

http://life.time.com/history/haile-se...

http://www.biography.com/people/haile...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haile_Se...

http://www.ethiopiantreasures.co.uk/p...

http://www.angelfire.com/ny/ethiocrow...

http://www.libcom.org/history/article...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Hai...

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/gener...

by Bereket Habte Selassie (no photo)

by Bereket Habte Selassie (no photo)

by Haile Selassie I (no photo)

by Haile Selassie I (no photo)

by Jeff Pearce (no photo)

by Jeff Pearce (no photo)

by Anthony Mockler (no photo)

by Anthony Mockler (no photo)

by

by

Theodore M. Vestal

Theodore M. Vestal

Haile Selassie I, original name Tafari Makonnen (born July 23, 1892, near Harer, Eth.—died Aug. 27, 1975, Addis Ababa), emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974 who sought to modernize his country and who steered it into the mainstream of post-World War II African politics. He brought Ethiopia into the League of Nations and the United Nations and made Addis Ababa the major centre for the Organization of African Unity (now African Union).

Tafari was a great-grandson of Sahle Selassie of Shewa (Shoa) and a son of Ras (Prince) Makonnen, a chief adviser to Emperor Menilek II. Educated at home by French missionaries, Tafari at an early age favourably impressed the emperor with his intellectual abilities and was promoted accordingly. As governor of Sidamo and then of Harer province, he followed progressive policies, seeking to break the feudal power of the local nobility by increasing the authority of the central government—for example, by developing a salaried civil service. He thereby came to represent politically progressive elements of the population. In 1911 he married Wayzaro Menen, a great-granddaughter of Menilek II.

When Menilek II died in 1913, his grandson Lij Yasu succeeded to the throne, but the latter’s unreliability and his close association with Islam made him unpopular with the majority Christian population of Ethiopia. Tafari became the rallying point of the Christian resistance, and he deposed Lij Yasu in 1916. Zauditu, Menilek II’s daughter, thereupon became empress in 1917, and Ras Tafari was named regent and heir apparent to the throne.

While Zauditu was conservative in outlook, Ras Tafari was progressive and became the focus of the aspirations of the modernist younger generation. In 1923 he had a conspicuous success in the admission of Ethiopia to the League of Nations. In the following year he visited Rome, Paris, and London, becoming the first Ethiopian ruler ever to go abroad. In 1928 he assumed the title of negus (“king”), and two years later, when Zauditu died, he was crowned emperor (Nov. 2, 1930) and took the name of Haile Selassie (“Might of the Trinity”). In 1931 he promulgated a new constitution, which strictly limited the powers of Parliament. From the late 1920s on, Haile Selassie in effect was the Ethiopian government, and, by establishing provincial schools, strengthening the police forces, and progressively outlawing feudal taxation, he sought to both help his people and increase the authority of the central government.

When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Haile Selassie led the resistance, but in May 1936 he was forced into exile. He appealed for help from the League of Nations in a memorable speech that he delivered to that body in Geneva on June 30, 1936. With the advent of World War II, he secured British assistance in forming an army of Ethiopian exiles in the Sudan. British and Ethiopian forces invaded Ethiopia in January 1941 and recaptured Addis Ababa several months later. Although he was reinstated as emperor, Haile Selassie had to recreate the authority he had previously exercised. He again implemented social, economic, and educational reforms in an attempt to modernize Ethiopian government and society on a slow and gradual basis.

The Ethiopian government continued to be largely the expression of Haile Selassie’s personal authority. In 1955 he granted a new constitution giving him as much power as the previous one. Overt opposition to his rule surfaced in December 1960, when a dissident wing of the army secured control of Addis Ababa and was dislodged only after a sharp engagement with loyalist elements.

Haile Selassie played a very important role in the establishment of the Organization of African Unity in 1963. His rule in Ethiopia continued until 1974, at which time famine, worsening unemployment, and the political stagnation of his government prompted segments of the army to mutiny. They deposed Haile Selassie and established a provisional military government that espoused Marxist ideologies. Haile Selassie was kept under house arrest in his own palace, where he spent the remainder of his life. Official sources at the time attributed his death to natural causes, but evidence later emerged suggesting that he had been strangled on the orders of the military government.

Haile Selassie was regarded as the messiah of the African race by the Rastafarian movement.

(Source:http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...)

More:

http://life.time.com/history/haile-se...

http://www.biography.com/people/haile...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haile_Se...

http://www.ethiopiantreasures.co.uk/p...

http://www.angelfire.com/ny/ethiocrow...

http://www.libcom.org/history/article...

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Hai...

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/gener...

by Bereket Habte Selassie (no photo)

by Bereket Habte Selassie (no photo) by Haile Selassie I (no photo)

by Haile Selassie I (no photo) by Jeff Pearce (no photo)

by Jeff Pearce (no photo) by Anthony Mockler (no photo)

by Anthony Mockler (no photo) by

by

Theodore M. Vestal

Theodore M. Vestal

message 309:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth and Baron Greenwich, was born Prince of Greece and Denmark in Corfu on 10 June 1921.

He was born the only son of Prince Andrew of Greece. His paternal family is of Danish descent - Prince Andrew was the grandson of King Christian IX of Denmark.

His mother was Princess Alice of Battenberg, the eldest child of Prince Louis of Battenberg and sister of Earl Mountbatten of Burma. Prince Louis became a naturalised British subject in 1868, joined the Royal Navy and rose to become an Admiral of the Fleet and First Sea Lord in 1914.

During the First World War Prince Louis changed the family name to Mountbatten and was created Marquess of Milford Haven. Prince Philip adopted the family name of Mountbatten when he became a naturalised British subject and renounced his Royal title in 1947.

Prince Louis married one of Queen Victoria's granddaughters. Thus, The Queen and Prince Philip both have Queen Victoria as a great-great-grandmother. They are also related through his father's side. His paternal grandfather, King George I of Greece, was Queen Alexandra's brother.

(Source:http://www.royal.gov.uk/thecurrentroy...)

More:

http://www.biography.com/people/princ...

http://www.infoplease.com/spot/royalb...

http://www.lifetimetv.co.uk/biography...

http://www.britroyals.com/family.asp?...

http://www.britainexpress.com/royals/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_P...

http://www.royal.gov.uk/ThecurrentRoy...

http://www.royal.gov.uk/thecurrentroy...

http://www.biography.com/people/princ...

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/artic...

by Lynne Bell (no photo)

by Lynne Bell (no photo)

by Philip Eade (no photo)

by Philip Eade (no photo)

by Andrzej Olechnowicz (no photo)

by Andrzej Olechnowicz (no photo)

by Andrew Marr (no photo)

by Andrew Marr (no photo)

by

by

Penny Junor

Penny Junor

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Merioneth and Baron Greenwich, was born Prince of Greece and Denmark in Corfu on 10 June 1921.

He was born the only son of Prince Andrew of Greece. His paternal family is of Danish descent - Prince Andrew was the grandson of King Christian IX of Denmark.

His mother was Princess Alice of Battenberg, the eldest child of Prince Louis of Battenberg and sister of Earl Mountbatten of Burma. Prince Louis became a naturalised British subject in 1868, joined the Royal Navy and rose to become an Admiral of the Fleet and First Sea Lord in 1914.

During the First World War Prince Louis changed the family name to Mountbatten and was created Marquess of Milford Haven. Prince Philip adopted the family name of Mountbatten when he became a naturalised British subject and renounced his Royal title in 1947.

Prince Louis married one of Queen Victoria's granddaughters. Thus, The Queen and Prince Philip both have Queen Victoria as a great-great-grandmother. They are also related through his father's side. His paternal grandfather, King George I of Greece, was Queen Alexandra's brother.

(Source:http://www.royal.gov.uk/thecurrentroy...)

More:

http://www.biography.com/people/princ...

http://www.infoplease.com/spot/royalb...

http://www.lifetimetv.co.uk/biography...

http://www.britroyals.com/family.asp?...

http://www.britainexpress.com/royals/...

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prince_P...

http://www.royal.gov.uk/ThecurrentRoy...

http://www.royal.gov.uk/thecurrentroy...

http://www.biography.com/people/princ...

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/artic...

by Lynne Bell (no photo)

by Lynne Bell (no photo) by Philip Eade (no photo)

by Philip Eade (no photo) by Andrzej Olechnowicz (no photo)

by Andrzej Olechnowicz (no photo) by Andrew Marr (no photo)

by Andrew Marr (no photo) by

by

Penny Junor

Penny Junor

message 311:

by

Jerome, Assisting Moderator - Upcoming Books and Releases

(new)

Larry O'Brien

Lawrence (Larry) O'Brien was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on 7th July, 1917. As a young man O'Brien met John F. Kennedy and helped him in his various political campaigns. This included managing his successful campaigns for the Senate in 1952 and 1958. O'Brien also played a significant role in Kennedy being elected president in 1960.

Kennedy appointed O'Brien as its special assistant in 1961. O'Brien was in the Presidential Motorcade in Dealey Plaza when Kennedy was assassinated. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed O'Brien as Postmaster General in 1965 and he held the post of three years.

O'Brien remained active in the Democratic Party and was chairman of the Democratic National Committee (1968–69 and 1970–73). He was also employed by Howard Hughes to protect his interests in Washington.

On 20th March, 1972 Frederick LaRue and John Mitchell of the Nixon's re-election committee decided to plant electronic devices in O'Brien's Democratic campaign offices in an apartment block calledWatergate. The plan was to wiretap O'Brien's conversations. Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barkerand E.Howard Hunt were later arrested and imprisoned for this crime.

O'Brien was also commissioner of the National Basketball Association (1975–84). His achievements included the merger of the ABA with the NBA, negotiating and signing a lucrative television contract with CBS, arranging a historic collective bargaining agreement with the NBA Players Association and introducing an innovative anti-drug program in 1983. In 1984, the NBA Championship Trophy was renamed the Larry O'Brien Championship Trophy.

Lawrence O'Brien died in New York on 28th September, 1990.

(Source:http://spartacus-educational.com/JFKo...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_O&...

http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/29/obi...

http://articles.latimes.com/1990-09-2...

http://mentalfloss.com/article/24894/...

http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Re...

http://www.masslive.com/tomshea/index...

http://millercenter.org/president/lbj...

http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/...

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

by W. Marvin Watson (no photo)

by W. Marvin Watson (no photo)

by Lady Bird Johnson (no photo)

by Lady Bird Johnson (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Irving Bernstein (no photo)

by Irving Bernstein (no photo)

by Sherwin J. Markman (no photo)

by Sherwin J. Markman (no photo)

Lawrence (Larry) O'Brien was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on 7th July, 1917. As a young man O'Brien met John F. Kennedy and helped him in his various political campaigns. This included managing his successful campaigns for the Senate in 1952 and 1958. O'Brien also played a significant role in Kennedy being elected president in 1960.

Kennedy appointed O'Brien as its special assistant in 1961. O'Brien was in the Presidential Motorcade in Dealey Plaza when Kennedy was assassinated. President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed O'Brien as Postmaster General in 1965 and he held the post of three years.

O'Brien remained active in the Democratic Party and was chairman of the Democratic National Committee (1968–69 and 1970–73). He was also employed by Howard Hughes to protect his interests in Washington.

On 20th March, 1972 Frederick LaRue and John Mitchell of the Nixon's re-election committee decided to plant electronic devices in O'Brien's Democratic campaign offices in an apartment block calledWatergate. The plan was to wiretap O'Brien's conversations. Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barkerand E.Howard Hunt were later arrested and imprisoned for this crime.

O'Brien was also commissioner of the National Basketball Association (1975–84). His achievements included the merger of the ABA with the NBA, negotiating and signing a lucrative television contract with CBS, arranging a historic collective bargaining agreement with the NBA Players Association and introducing an innovative anti-drug program in 1983. In 1984, the NBA Championship Trophy was renamed the Larry O'Brien Championship Trophy.

Lawrence O'Brien died in New York on 28th September, 1990.

(Source:http://spartacus-educational.com/JFKo...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Larry_O&...

http://www.nytimes.com/1990/09/29/obi...

http://articles.latimes.com/1990-09-2...

http://mentalfloss.com/article/24894/...

http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Re...

http://www.masslive.com/tomshea/index...

http://millercenter.org/president/lbj...

http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/...

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

by W. Marvin Watson (no photo)

by W. Marvin Watson (no photo) by Lady Bird Johnson (no photo)

by Lady Bird Johnson (no photo) by Jeff Shesol (no photo)

by Jeff Shesol (no photo) by Irving Bernstein (no photo)

by Irving Bernstein (no photo) by Sherwin J. Markman (no photo)

by Sherwin J. Markman (no photo)

Ben Bradlee

Ben Bradlee

As a reporter in the 1950s, Bradlee became close friends with then-senator John F. Kennedy, who had graduated from Harvard two years before Bradlee, and lived nearby. Bradlee's wife at the time, Jean Saltonstall, was related to Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy through her father's sister Rosamund who married Charles Auchincloss. In 1960 Bradlee toured with both Kennedy and Richard Nixon in their presidential campaigns. He later wrote a book, Conversations With Kennedy, recounting their relationship during those years. Bradlee was, at this point, Washington Bureau chief for Newsweek, a position from which he helped negotiate the sale of the magazine to The Washington Post holding company. Bradlee maintained that position until being promoted to managing editor at the Post in 1965. He became executive editor in 1968, and on October 20, 1978, he married fellow journalist Sally Quinn. Quinn and Bradlee have one child, Quinn Bradlee, who was born in 1982 when Quinn was 41 and Bradlee was 61. In 2009 they appeared with Quinn Bradlee on the Charlie Rose show on PBS and spoke of their son's having been born with Velo-cardio-facial syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome and Shprintzen syndrome (named after Dr. Robert Shprintzen, who first identified the disorder in 1978 and who also diagnosed Quinn Bradlee).

Bradlee retired as the executive editor of The Washington Post in September 1991 but continued to serve as vice president at large until his death. He was succeeded as executive editor at the Post by Leonard Downie Jr., whom Bradlee had appointed as managing editor seven years earlier.

Under Bradlee's leadership, The Washington Post took on major challenges during the Nixon administration. In 1971 The New York Times and the Post successfully challenged the government over the right to publish the Pentagon Papers. One year later, Bradlee backed reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein as they probed the break-in at the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate Hotel. According to Bradlee:

"You had a lot of Cuban or Spanish-speaking guys in masks and rubber gloves, with walkie-talkies, arrested in the Democratic National Committee Headquarters at 2 in the morning. What the hell were they in there for? What were they doing? The follow-up story was based primarily on their arraignment in court, and it was based on information given our police reporter, Al Lewis, by the cops, showing them an address book that one of the burglars had in his pocket, and in the address book was the name 'Hunt,' H-u-n-t, and the phone number was the White House phone number, which Al Lewis and every reporter worth his salt knew. And when, the next day, Woodward—this is probably Sunday or maybe Monday, because the burglary was Saturday morning early—called the number and asked to speak to Mr. Hunt, and the operator said, 'Well, he's not here now; he's over at' such-and-such a place, gave him another number, and Woodward called him up, and Hunt answered the phone, and Woodward said, 'We want to know why your name was in the address book of the Watergate burglars.' And there is this long, deathly hush, and Hunt said, 'Oh my God!' and hung up. So you had the White House. You have Hunt saying 'Oh my God!' At a later arraignment, one of the guys whispered to a judge. The judge said, 'What do you do?' and Woodward overheard the words 'CIA.' So if your interest isn't whetted by this time, you're not a journalist."

Ensuing investigations of suspected cover-ups led inexorably to congressional committees, conflicting testimonies, and ultimately to the resignation of Richard Nixon in 1974. For decades, Bradlee was one of only four publicly known people who knew the true identity of press informant Deep Throat, the other three being Woodward, Bernstein, and Deep Throat himself, who later revealed himself to be Nixon's FBI associate director Mark Felt.

In 1981 Post reporter Janet Cooke won a Pulitzer Prize for "Jimmy's World", a profile of an 8-year-old heroin addict. Cooke's article turned out to be fiction: there was no such addict. As executive editor, Bradlee was roundly criticized in many circles for failing to ensure the article's accuracy. After questions about the story's veracity arose, Bradlee (along with publisher Donald Graham) ordered a "full disclosure" investigation to ascertain the truth. Bradlee personally apologized to Mayor Marion Barry and the chief of police of Washington, D.C., for the Post's fictitious article. Cooke, meanwhile, was forced to resign and relinquish the Pulitzer.

Bradlee published an autobiography in 1995, A Good Life: Newspapering and Other Adventures. He had an acting role in Born Yesterday, the 1993 remake of the 1950 romantic comedy. In 1983 he gave the inaugural Vance Distinguished Lecture at Central Connecticut State University. On May 3, 2006, Bradlee received a Doctor of Humane Letters from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. Prior to receiving the honorary degree, he taught occasional journalism courses at Georgetown.

In 1991 he was persuaded by then–governor of Maryland William Donald Schaefer to accept the chairmanship of the Historic St. Mary's City Commission and continued in that position through 2003. He also served for many years as a member of the board of trustees at St. Mary's College of Maryland, and endowed the Benjamin C. Bradlee Annual Lecture in Journalism there. He continued to serve as vice chairman of the school's board of trustees.

In the fall of 2005, Jim Lehrer conducted six hours of interviews with Bradlee on a variety of topics, from the responsibilities of the press to Watergate to the Valerie Plame affair. The interviews were edited for an hour-long documentary, Free Speech: Jim Lehrer and Ben Bradlee, which premiered on PBS on June 19, 2006.

At The Washington Post, Bradlee carried the title vice president at large. He and Quinn lived at the Todd Lincoln House in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. The middle part of the house was built in 1792. They also restored Porto Bello, their home in Drayden, Maryland.

Bradlee received the French Legion of Honor, the highest award given by the French government, at a ceremony in 2007 in Paris.

Bradlee was named as a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama on August 8, 2013, and was presented the medal at a White House ceremony on November 20, 2013.

In late September 2014, Bradlee entered hospice care due to declining health as a result of Alzheimer's disease. He died of natural causes on October 21, 2014, at his home in Washington, D.C., at the age of 93. His funeral was held at the Washington National Cathedral on October 29. He was buried at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C. afterwards. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ben_Bradlee)

More:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/...

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/22/bus...

http://nymag.com/news/features/ben-br...

http://www.npr.org/2014/10/21/3527587...

http://time.com/3450585/ben-bradlee-2/

by Ben Bradlee(no photo)

by Ben Bradlee(no photo) by Benjamin C. Bradlee(no photo)

by Benjamin C. Bradlee(no photo) by The Washington Post (no photo)

by The Washington Post (no photo) by The Washington Post(no photo)

by The Washington Post(no photo) by

by

Carl Bernstein

Carl Bernstein

message 313:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Dec 19, 2014 06:50PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

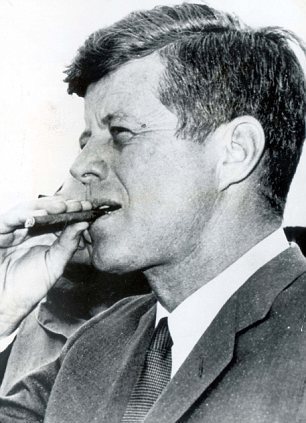

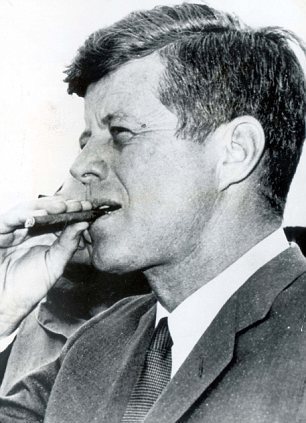

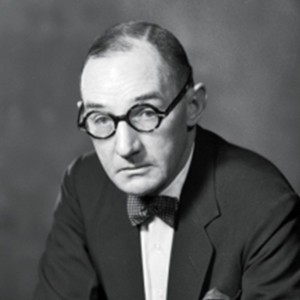

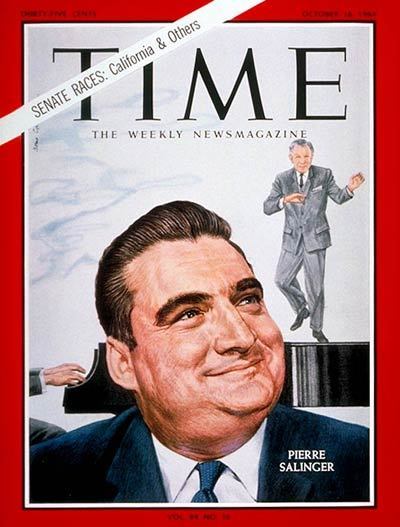

How John F. Kennedy got 1,200 hand rolled Cuban cigars just hours before he ordered his trade embargo against Castro more than 53 years ago

JFK's press secretary told the story on video before his death, describing a evening mad dash to buy up the president's favorite Cuban stogies

Pierre Salinger laid his hands on 1,200 H.Upmann cigars in Kennedy's favorite size – in just one night

After JFK found out he had all the cigars he would need, he immediately signed the trade embargo declaring future purchases illegal

President Barack Obama relaxed trade sanctions against Cuba on Wednesday, allowing US travelers to Cuba to bring back up to $100 worth of cigars - That amount would buy no more than 10 of JFK's favorite smokes today on the open market

By David Martosko, US Political Editor for MailOnline

PARTNERS IN CRIME - Pierre Salinger (was a regular cigar smoker, so he asked all the stores he knew to sell him every H. Upmann 'petit' cigar they had so JFK could stock up)

Here is a very funny video with Pierre Salinger telling the story: (it is embedded in this article - just scroll down and you will see the video).

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/artic...

JFK's press secretary told the story on video before his death, describing a evening mad dash to buy up the president's favorite Cuban stogies

Pierre Salinger laid his hands on 1,200 H.Upmann cigars in Kennedy's favorite size – in just one night

After JFK found out he had all the cigars he would need, he immediately signed the trade embargo declaring future purchases illegal

President Barack Obama relaxed trade sanctions against Cuba on Wednesday, allowing US travelers to Cuba to bring back up to $100 worth of cigars - That amount would buy no more than 10 of JFK's favorite smokes today on the open market

By David Martosko, US Political Editor for MailOnline

PARTNERS IN CRIME - Pierre Salinger (was a regular cigar smoker, so he asked all the stores he knew to sell him every H. Upmann 'petit' cigar they had so JFK could stock up)

Here is a very funny video with Pierre Salinger telling the story: (it is embedded in this article - just scroll down and you will see the video).

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/artic...

John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth "Ken" Galbraith (October 15, 1908 – April 29, 2006) was a Canadian and, later, American economist, public official, and diplomat, and a leading proponent of 20th-century American liberalism. His books on economic topics were bestsellers from the 1950s through the 2000s, during which time Galbraith fulfilled the role of public intellectual. As an economist, he was a Keynesian and an institutionalist.

Galbraith was a long-time Harvard faculty member and stayed with Harvard University for half a century as a professor of economics.[3] He was a prolific author and wrote four dozen books, including several novels, and published more than a thousand articles and essays on various subjects. Among his most famous works was a popular trilogy on economics, American Capitalism (1952), The Affluent Society (1958), and The New Industrial State (1967).

Galbraith was active in Democratic Party politics, serving in the administrations of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson. He served as United States Ambassador to India under the Kennedy administration. His prodigious literary output and outspokenness made him, arguably, "the best-known economist in the world" during his lifetime. Galbraith was one of few recipients both of the Medal of Freedom (1946) and the Presidential Medal of Freedom (2000) for his public service and contribution to science. The government of France made him a Commandeur de la Légion d'honneur.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ken...)

More:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1000142...

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bi...

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/30/obi...

http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/aut...

http://globetrotter.berkeley.edu/conv...

by Jacqueline Bloom Stanfield (no photo)

by Jacqueline Bloom Stanfield (no photo) by Andrea Williams (no photo)

by Andrea Williams (no photo) by Jim Dell (no photo)

by Jim Dell (no photo) by Richard Parker (no photo)

by Richard Parker (no photo)

all by

all by

John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith

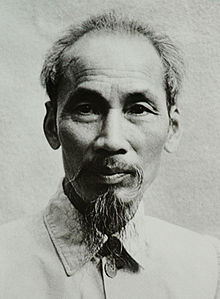

Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh

Ho Chi Minh led the Vietnamese nationalist movement for more than three decades, fighting first against the Japanese, then the French colonial power and then the US-backed South Vietnamese. He was President of North Vietnam from 1954 until his death.

Ho Chi Minh (originally Nguyen That Thanh) was born on 19 May 1890 in Hoang Tru in central Vietnam. Vietnam was then a French colony, known as French Indo-China, but under the nominal rule of an emperor. Ho's father worked at the imperial court but was dismissed for criticising the French colonial power.

In 1911, Ho took a job on a French ship and travelled widely. He lived in London and Paris, and was a founding member of the French communist party. In 1923, he visited Moscow for training at Comintern, an organisation created by Lenin to promote worldwide revolution. He travelled to southern China to organise a revolutionary movement among Vietnamese exiles, and in 1930 founded the Indo-Chinese Communist Party (ICP). He spent the 1930s in the Soviet Union and China.

After the Japanese invasion of Indo-China in 1941, Ho returned home and founded the Viet Minh, a communist-dominated independence movement, to fight the Japanese. He adopted the name Ho Chi Minh, meaning 'Bringer of Light'.

At the end of World War Two the Viet Minh announced Vietnamese independence. The French refused to relinquish their colony and in 1946, war broke out. After eight years of war, the French were forced to agree to peace talks in Geneva. The country was split into a communist north and non-communist south and Ho became president of North Vietnam. He was determined to reunite Vietnam under communist rule.

By the early 1960s, North Vietnamese-backed guerrillas, the Vietcong, were attacking the South Vietnamese government. Fearing the spread of communism, the United States provided increasing levels of support to South Vietnam. By 1965, large numbers of American troops were arriving and the fighting escalated into a major conflict.

Ho Chi Minh was in poor health from the mid-1960s and died on 2 September 1969. When the Communists took the South Vietnamese capital Saigon in 1975 they renamed it Ho Chi Minh City in his honour. (Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ho_Chi_Minh

http://spartacus-educational.com/VNho...

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/gener...

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/honor/pe...

by Philip Steele (no photo)

by Philip Steele (no photo) by Milton E. Osborne (no photo)

by Milton E. Osborne (no photo) by Pierre Brocheux (no photo)

by Pierre Brocheux (no photo) by Lady Borton (no photo)

by Lady Borton (no photo) by

by

William J. Duiker

William J. Duiker

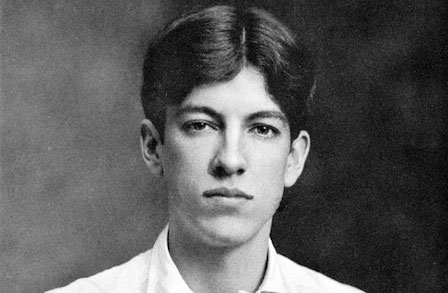

Alan Seeger

Alan Seeger

Alan Seeger (22 June 1888 – 4 July 1916) was an American poet who fought and died in World War I during the Battle of the Somme serving in the French Foreign Legion. Seeger was the uncle of American folk singer Pete Seeger, and was a classmate of T.S. Eliot at Harvard. He is most well known for having authored the poem, I Have a Rendezvous with Death, a favorite of President John F. Kennedy. A statue modeled after Seeger is found on the monument honoring fallen Americans who volunteered for France during the war, located at the Place des États-Unis, Paris. He is sometimes called the "American Rupert Brooke."

Born in New York on June 22, 1888, Seeger moved with his family to Staten Island at the age of one and remained there until the age of 10. In 1900, his family moved to Mexico for two years, which influenced the imagery of some of his poetry. His brother Charles Seeger, a noted pacifist and musicologist, was the father of the American folk singers Peter "Pete" Seeger, Mike Seeger, and Margaret "Peggy" Seeger.

Seeger entered Harvard in 1906 after attending several elite preparatory schools, including Hackley School.

At Harvard, he edited and wrote for the Harvard Monthly. Among his friends there (and afterward) was the American Communist John Reed, though the two had differing ideological views, and his Harvard class also included T.S. Eliot and Walter Lippmann, among others. After graduating in 1910, he moved to Greenwich Village for two years, where he wrote poetry and enjoyed the life of a young bohemian. During his time in Greenwich Village, he attended soirées at the Mlles. Petitpas' boardinghouse (319 West 29th Street), where the presiding genius was the artist and sage John Butler Yeats, father of the poet William Butler Yeats.

Having moved to the Latin Quarter of Paris to continue his seemingly itinerant intellectual lifestyle, on August 24, 1914, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion so that he could fight for the Allies in World War I (the United States did not enter the war until 1917).

He was killed in action at Belloy-en-Santerre on July 4, 1916, famously cheering on his fellow soldiers in a successful charge after being hit several times by machine gun fire.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Seeger)

"I Have a Rendezvous with Death"

poem by Alan Seeger

I have a rendezvous with Death

At some disputed barricade,

When Spring comes back with rustling shade

And apple-blossoms fill the air-

I have a rendezvous with Death

When Spring brings back blue days and fair.

It may be he shall take my hand

And lead me into his dark land

And close my eyes and quench my breath-

It may be I shall pass him still.

I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,

When Spring comes round again this year

And the first meadow-flowers appear.

God knows 'twere better to be deep

Pillowed in silk and scented down,

Where love throbs out in blissful sleep,

Pulse nigh to pulse, and breath to breath,

Where hushed awakenings are dear...

But I've a rendezvous with Death

At midnight in some flaming town,

When Spring trips north again this year,

And I to my pledged word am true,

I shall not fail that rendezvous.

(Source: http://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Re...)

More:

http://www.english.emory.edu/LostPoet...

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-hi...

http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/a...

http://net.lib.byu.edu/estu/wwi/memoi...

http://www.scuttlebuttsmallchow.com/a...

by M. Paul Holsinger (no photo)

by M. Paul Holsinger (no photo) by Ann M. Pescatello (no photo)

by Ann M. Pescatello (no photo) by N. P. Dawson (no photo)

by N. P. Dawson (no photo)

both by

both by

Alan Seeger

Alan Seeger

Battle of Dien Bien Phu

Battle of Dien Bien Phu

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu was the decisive engagement in the first Indochina War (1946–54). After French forces occupied the Dien Bien Phu valley in late 1953, Viet Minh commander Vo Nguyen Giap amassed troops and placed heavy artillery in caves of the mountains overlooking the French camp. Boosted by Chinese aid, Giap mounted assaults on the opposition’s strong points beginning in March 1954, eliminating use of the French airfield. Viet Minh forces overran the base in early May, prompting the French government to seek an end to the fighting with the signing of the Geneva Accords of 1954.

The battle that settled the fate of French Indochina was initiated in November 1953, when Viet Minh forces at Chinese insistence moved to attack Lai Chau, the capital of the T’ai Federation (in Upper Tonkin), which was loyal to the French. As Peking had hoped, the French commander in chief in Indochina, General Henri Navarre, came out to defend his allies because he believed the T’ai “maquis” formed a significant threat in the Viet Minh “rear” (the T’ai supplied the French with opium that was sold to finance French special operations) and wanted to prevent a Viet Minh sweep into Laos. Because he considered Lai Chau impossible to defend, on November 20, Navarre launched Operation Castor with a paratroop drop on the broad valley of Dien Bien Phu, which was rapidly transformed into a defensive perimeter of eight strong points organized around an airstrip. When, in December 1953, the T’ais attempted to march out of Lai Chau for Dien Bien Phu, they were badly mauled by Viet Minh forces.

Viet Minh commander Vo Nguyen Giap,with considerable Chinese aide, massed troops and placed heavy artillery in caves in the mountains overlooking the French camp. On March 13, 1954, Giap launched a massive assault on strong point Beatrice, which fell in a matter of hours. Strong points Gabrielle and Anne-Marie were overrun during the next two days, which denied the French use of the airfield, the key to the French defense. Reduced to airdrops for supplies and reinforcement, unable to evacuate their wounded, under constant artillery bombardment, and at the extreme limit of air range, the French camp’s morale began to fray. As the monsoons transformed the camp from a dust bowl into a morass of mud, an increasing number of soldiers–almost four thousand by the end of the siege in May–deserted to caves along the Nam Yum River, which traversed the camp; they emerged only to seize supplies dropped for the defenders. The “Rats of Nam Yum” became POWs when the garrison surrendered on May 7th.

Despite these early successes, Giap’s offensives sputtered out before the tenacious resistance of French paratroops and legionnaires. On April 6, horrific losses and low morale among the attackers caused Giap to suspend his offensives. Some of his commanders, fearing U.S. air intervention, began to speak of withdrawal. Again, the Chinese, in search of a spectacular victory to carry to the Geneva talks scheduled for the summer, intervened to stiffen Viet Minh resolve: reinforcements were brought in, as were Katyusha multitube rocket launchers, while Chinese military engineers retrained the Viet Minh in siege tactics. When Giap resumed his attacks, human wave assaults were abandoned in favor of siege techniques that pushed forward webs of trenches to isolate French strong points. The French perimeter was gradually reduced until, on May 7, resistance ceased. The shock and agony of the dramatic loss of a garrison of around fourteen thousand men allowed French prime minister Pierre Mendes to muster enough parliamentary support to sign the Geneva Accords of July 1954, which essentially ended the French presence in Indochina. (Source: http://www.history.com/topics/battle-...)

More:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_o...

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://www.historynet.com/battle-of-d...

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-2724...

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/...

by Ricky Balona (no photo)

by Ricky Balona (no photo) by

by

John Keegan

John Keegan by

by

Pierre Langlais

Pierre Langlais by

by

Howard R. Simpson

Howard R. Simpson by

by

Bernard B. Fall

Bernard B. Fall

Martin wrote: "Wow. Something in that gene pool, no?"

Martin hard to believe they were all compatriots.

Martin hard to believe they were all compatriots.

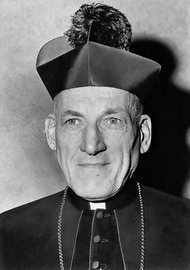

St. Matthew's Cathedral

St. Matthew's Cathedral

The Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle in Washington D.C., most commonly known as St. Matthew's Cathedral, is the seat of the Archbishop (currently Donald Cardinal Wuerl) of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington. As St. Matthew's Cathedral and Rectory, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

The cathedral is located in downtown Washington at 1725 Rhode Island Avenue NW between Connecticut Avenue and 17th Street. The closest Metrorail station is Farragut North, on the Red Line.

St. Matthew's is dedicated to the Apostle Matthew, who among other things is patron saint of civil servants, having himself been a tax collector, and was established in 1840 as the fourth Catholic parish in the District of Columbia. Originally located at 15th and H Streets, construction of the current church began in 1893, with the first Mass being celebrated June 2, 1895. Construction continued until 1913 when the church was finally dedicated. In 1939, it became cathedral for the newly established Archdiocese of Washington.

The structure is constructed of red brick with sandstone and terra cotta trim in the Romanesque Revival style with Byzantine elements. Designed by architect C. Grant La Farge, it is in the shape of a Latin cross measuring 155 ft × 136 ft (47 m × 41 m) and seats about 1,200 persons. The interior is richly decorated in marble and semiprecious stones, notably a 35 ft (11 m) mosaic of Matthew behind the main altar by Edwin Blashfield. The cathedral is capped by an octagonal dome that extends 190 ft (58 m) above the nave and is capped by a cupola and crucifix that brings the total height to 200 ft (61 m). Both structural and decorative elements underwent extensive restoration between 2000 and September 21, 2003, the Feast day of St. Matthew.

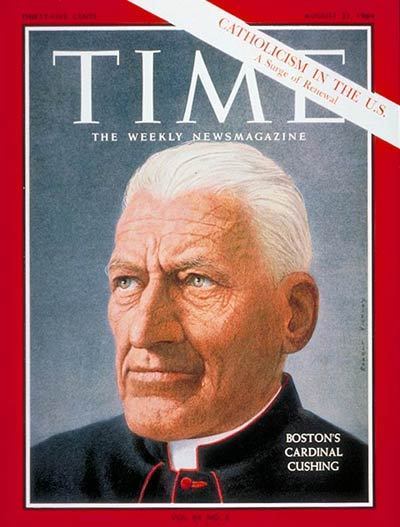

The first notable funeral Mass offered there was for Philippine President Manuel L. Quezon, who died August 1, 1944, and was intered at Arlington National Cemetery until the end of World War II. In 1957, a Solemn Requiem Mass was offered at the cathedral for the funeral of Senator Joseph McCarthy; the liturgy was attended by 70 senators and hundreds of clergymen. The cathedral drew world attention on November 25, 1963, when Richard Cardinal Cushing, Archbishop of Boston and a Kennedy family friend, offered a recited (not sung) Pontifical Requiem Low Mass during the state funeral of President John F. Kennedy. Other notable events at the cathedral include a Mass celebrated by Pope John Paul II during his 1979 visit to Washington, D.C. and the 1997 funeral of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice William J. Brennan, Jr..

The cathedral was also the site of a Lutheran funeral service for Chief Justice William Rehnquist on September 7, 2005.

St. Matthew's is the location for one of the most famous Red Masses in the world. Each year on the day before the term of the Supreme Court of the United States begins, Mass is celebrated to request guidance from the Holy Spirit for the legal profession. Owing to the Cathedral's location in the nation's capital, the Justices of the Supreme Court, members of Congress and the Cabinet, and many other dignitaries (including, at times, the President of the United States) attend the Mass.

Near the entry of the St. Francis Chapel is a burial crypt with eight tombs intended for Washington’s archbishops. Currently two former archbishops, Patrick Cardinal O’Boyle and James Cardinal Hickey, are interred here. (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cathedra...)

More:

http://www.stmatthewscathedral.org/

http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc5...

http://stmatthew.webhero.com/cathedra...

http://www.jfklibrary.org/Asset-Viewe...

http://www.adw.org/parishes/search/pa...

(no image) Saints Alive!: A Book of Patron Saints by Enid Broderick Fisher(no photo)

by E. Jacquier (no photo)

by E. Jacquier (no photo) Jesse Russell (no photo)

Jesse Russell (no photo) by Jesse Russell (no photo)

by Jesse Russell (no photo) by Mina Rieur Weiner (no photo)

by Mina Rieur Weiner (no photo)

Theodore C. Sorensen with President John F. Kennedy in the Oval Office in 1961 - George Thames - New York Times

Here is Theodore Sorensen's obituary written by the History Book Club's good friend and author - Tim Weiner.

Theodore C. Sorensen, 82, Kennedy Counselor, Dies

By TIM WEINER

Published: October 31, 2010

Theodore C. Sorensen, one of the last links to John F. Kennedy’s administration, a writer and counselor who did much to shape the president’s narrative, image and legacy, died Sunday in Manhattan. He was 82.

His death, at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, was from complications of a stroke he suffered a week ago, his wife, Gillian Sorensen, said.

Mr. Sorensen once said he suspected that the headline on his obituary would read “Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy Speechwriter,” misspelling his name and misjudging his work, but he was much more. He was a political strategist and a trusted adviser on everything from election tactics to foreign policy.

“You need a mind like Sorensen’s around you that’s clicking and clicking all the time,” Kennedy’s archrival, Richard M. Nixon, said in 1962. He said Mr. Sorensen had “a rare gift”: the knack of finding phrases that penetrated the American psyche.

He was best known for working with Kennedy on passages of soaring rhetoric, including the 1961 inaugural address proclaiming that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans” and challenging citizens: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Mr. Sorensen drew on the Bible, the Gettysburg Address and the words of Thomas Jefferson and Winston Churchill as he helped hone and polish that speech.

First hired as a researcher by Kennedy, a newly elected senator from Massachusetts who took office in 1953, Mr. Sorensen collaborated closely — more closely than most knew — on “Profiles in Courage,” the 1956 book that won Kennedy a Pulitzer Prize and a national audience.

After the president’s assassination, Mr. Sorensen practiced law and politics. But in the public mind, his name was forever joined to the man he had served; his first task after leaving the White House was to recount the abridged administration’s story in a 783-page best seller simply titled “Kennedy.”

He held the title of special counsel, but Washington reporters of the era labeled him the president’s “intellectual alter ago” and “a lobe of Kennedy’s mind.” Mr. Sorensen called these exaggerations, but they were rooted in some truth.

Kennedy had plenty of yes-men. He needed a no-man from time to time. The president trusted Mr. Sorensen to play that role in crises foreign and domestic, and he played it well, in the judgment of Robert F. Kennedy, his brother’s attorney general. “If it was difficult,” Robert Kennedy said, “Ted Sorensen was brought in.”

Mr. Sorensen was proudest of a work written in haste, under crushing pressure. In October 1962, when he was 34 years old, he drafted a letter from Kennedy to the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, which helped end the Cuban missile crisis. After the Kennedy administration’s failed coup against Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs, the Soviets had sent nuclear weapons to Cuba. They were capable of striking most American cities, including New York and Washington.

“Time was short,” Mr. Sorensen remembered in an interview with The New York Times that was videotaped to accompany this obituary. “The hawks were rising. Kennedy could keep control of his own government, but one never knew whether the advocates of bombing and invasion might somehow gain the upper hand.”

Mr. Sorensen said, “I knew that any mistakes in my letter — anything that angered or soured Khrushchev — could result in the end of America, maybe the end of the world.”

The letter pressed for a peaceful solution. The Soviets withdrew the missiles. The world went on.

Theodore Chaikin Sorensen was born in Lincoln, Neb., on May 8, 1928 — Harry S. Truman’s 44th birthday, as he was fond of noting. He described himself as a distinct minority: “a Danish Russian Jewish Unitarian.” He was the son of Christian A. Sorensen, a lawyer, and Annis Chaikin, a social worker, pacifist and feminist. His father, a Republican who had named him after Teddy Roosevelt, ran for public office for the first time that year; he served as Nebraska’s attorney general from 1929 to 1933.

Lincoln, the state capital, was named for the 16th president. Near the Statehouse stood a statue of Abraham Lincoln and a slab with the full text of the Gettysburg Address. As a child, Mr. Sorensen read it over and over. The Capitol itself held engraved quotations; one he remembered was “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Mr. Sorensen earned undergraduate and law degrees at the University of Nebraska and, on July 1, 1951, at the age of 23, he left Lincoln to seek his fortune in Washington. He knew no one. He had no appointments, phone numbers or contacts. Except for a hitchhiking trip to Texas, he had never left the Midwest. He had never had a cup of coffee or written a check.

Eighteen months later, after short stints as a junior government lawyer, he was hired by John F. Kennedy, the new Democratic senator from Massachusetts. Kennedy was “young, good-looking, glamorous, rich, a war hero, a Harvard graduate,” Mr. Sorensen recalled. The new hire was none of those, save young. They quickly found that they shared political ideals and values.

“When he first hired me,” Mr. Sorensen recalled, Kennedy said, “ ‘I want you to put together a legislative program for the economic revival of New England.’ ” Kennedy’s first three speeches on the Senate floor — late in the evening, when nobody was around — presented the program Mr. Sorensen proposed.

Kennedy made his mark with “Profiles in Courage,” published in January 1956. It was no great secret that Mr. Sorensen’s intellect was an integral part of the book. “I’ve tried to keep it a secret,” he said jokingly in his interview with The Times. But Mr. Sorensen drafted most of the chapters, and Kennedy paid him for his work. “I’m proud to say I played an important role,” Mr. Sorensen said.

He spent most of the next four years working to make his boss the president of the United States. “We traveled together to all 50 states,” Mr. Sorensen wrote in his book “Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History,” a memoir published in 2008, “most of them more than once, initially just the two of us.” There was no entourage until Kennedy won the Democratic nomination in 1960. It was not clear at the outset that he could do that, much less capture the White House.

“It was only after we had crisscrossed the country and began to build support at the grass roots, largely unrecognized in Washington, where Kennedy was dismissed as being too young, too Catholic, too little known, too inexperienced,” Mr. Sorensen said in the interview.

In those travels, Mr. Sorensen found his own voice as well as Kennedy’s. “Everything evolved during those three-plus years that we were traveling the country together,” he said. “He became a much better speaker. I became much more equipped to write speeches for him. Day after day after day after day, he’s up there on the platform speaking, and I’m sitting in the audience listening, and I find out what works and what doesn’t, what fits his style.”

The Kennedy White House was never a Camelot: “Neither Kennedy nor any of us who worked with him were mythical characters who had magical powers,” Mr. Sorensen said, “and we obviously had our share of mistakes.” But Mr. Sorensen was not ashamed to say he worshipped Kennedy. He was devastated by his assassination in November 1963.

“It was a feeling of hopelessness,” he said, “of anger, of bitterness. That there was nothing we could do. There was nothing I could do.”

For more than 40 years after he left the White House, Mr. Sorensen practiced law, mostly as a senior partner at the New York firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. He counseled leaders like Nelson Mandela of South Africa and Anwar Sadat of Egypt.

His life went on, in public and private; he was writing and making speeches well past his 80th birthday. But it was never the same.

In 1970, two years after Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated on the presidential campaign trail, Mr. Sorensen ran for the Senate seat that Robert Kennedy had held in New York. The run was a mistake, he conceded. “I simply thought that if I were to carry on the Kennedy legacy, if I were to perpetuate the ideals of John Kennedy, as Robert Kennedy tried to do, that I would need to be in public office,” he said. “Frankly, it was an act of hubris on my part.”

In December 1976, out of the blue, President-elect Jimmy Carter offered Mr. Sorensen the post of director of central intelligence.

“I had to make a very quick decision,” Mr. Sorensen remembered. “I did not know whether a lawyer and a moralist was suitable for a position that presides over all kinds of law-breaking and immoral activities. But I wanted to be involved. I wanted to be back in government at a position where I could help things in a sound and progressive way, and so I said, ‘Yes, I accept.’ ”

Opponents of the nomination pointed out a potential problem. More than 30 years before, after the end of World War II, Mr. Sorensen, not yet 18, had registered with his draft board as a conscientious objector to combat. President-elect Carter’s top aide, Hamilton Jordan, placed an angry call to Mr. Sorensen, asking why he had not mentioned this suddenly salient fact before accepting the nomination.

“I said, ‘I didn’t know that the C.I.A. director was supposed to kill anybody,’ ” Mr. Sorensen recalled. “He wasn’t too happy with that answer.”

The nomination was withdrawn. That ended Mr. Sorensen’s ambition to return to work in Washington.

A stroke in 2001 took away much of his eyesight, but afterward Mr. Sorensen continued to lead “a very full life, speaking, writing, creating new enterprises and mentoring many young people,” his wife said.

Mr. Sorensen remained active in Democratic politics and took a particular liking to a freshman senator from Illinois, Barack Obama, when he arrived in Washington in 2005. When Mr. Obama began running for president two years later, Mr. Sorensen endorsed his candidacy and campaigned across the country, particularly to audiences who were opposed to the Iraq war.

“It reminds me of the way the young, previously unknown J. F. K. took off,” Mr. Sorensen said in an interview with The Times in 2007.

A year after Mr. Obama took office, Mr. Sorensen acknowledged frustration with his presidency, particularly the decision to send more troops to Afghanistan, a conflict that he called “Obama’s Vietnam.” But, Mr. Sorensen said, “The foreign policy problems are more difficult than they were in Kennedy’s day.”

“I still think it was amazing that a man with his skin color — and also he was a liberal Democrat, let’s face it — was elected,” Mr. Sorensen said in a 2009 interview in his Manhattan apartment, where a photograph of Mr. Obama joined a tableau of images from the Kennedy administration. “I haven’t the slightest doubt that there are a lot of white men who still find it difficult to accept the fact, the reality, that we have a black president in this country.”

President Obama said Sunday in a statement, “I know his legacy will live on in the words he wrote, the causes he advanced, and the hearts of anyone who is inspired by the promise of a new frontier.”

Mr. Sorensen’s 1949 marriage to Camilla Palmer and his 1964 marriage to Sara Elbery ended in divorce. In 1969 he married Gillian Martin. Besides his wife, he is survived by their daughter, Juliet Sorensen Jones; three sons from his first marriage, Eric, Stephen and Phil; a sister, Ruth Singer; a brother, Phillip; and seven grandchildren.

Theodore C. Sorensen, 82, Kennedy Counselor, Dies

By TIM WEINER

Published: October 31, 2010

Theodore C. Sorensen, one of the last links to John F. Kennedy’s administration, a writer and counselor who did much to shape the president’s narrative, image and legacy, died Sunday in Manhattan. He was 82.

His death, at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital, was from complications of a stroke he suffered a week ago, his wife, Gillian Sorensen, said.

Mr. Sorensen once said he suspected that the headline on his obituary would read “Theodore Sorenson, Kennedy Speechwriter,” misspelling his name and misjudging his work, but he was much more. He was a political strategist and a trusted adviser on everything from election tactics to foreign policy.

“You need a mind like Sorensen’s around you that’s clicking and clicking all the time,” Kennedy’s archrival, Richard M. Nixon, said in 1962. He said Mr. Sorensen had “a rare gift”: the knack of finding phrases that penetrated the American psyche.

He was best known for working with Kennedy on passages of soaring rhetoric, including the 1961 inaugural address proclaiming that “the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans” and challenging citizens: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Mr. Sorensen drew on the Bible, the Gettysburg Address and the words of Thomas Jefferson and Winston Churchill as he helped hone and polish that speech.

First hired as a researcher by Kennedy, a newly elected senator from Massachusetts who took office in 1953, Mr. Sorensen collaborated closely — more closely than most knew — on “Profiles in Courage,” the 1956 book that won Kennedy a Pulitzer Prize and a national audience.

After the president’s assassination, Mr. Sorensen practiced law and politics. But in the public mind, his name was forever joined to the man he had served; his first task after leaving the White House was to recount the abridged administration’s story in a 783-page best seller simply titled “Kennedy.”

He held the title of special counsel, but Washington reporters of the era labeled him the president’s “intellectual alter ago” and “a lobe of Kennedy’s mind.” Mr. Sorensen called these exaggerations, but they were rooted in some truth.

Kennedy had plenty of yes-men. He needed a no-man from time to time. The president trusted Mr. Sorensen to play that role in crises foreign and domestic, and he played it well, in the judgment of Robert F. Kennedy, his brother’s attorney general. “If it was difficult,” Robert Kennedy said, “Ted Sorensen was brought in.”

Mr. Sorensen was proudest of a work written in haste, under crushing pressure. In October 1962, when he was 34 years old, he drafted a letter from Kennedy to the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, which helped end the Cuban missile crisis. After the Kennedy administration’s failed coup against Fidel Castro at the Bay of Pigs, the Soviets had sent nuclear weapons to Cuba. They were capable of striking most American cities, including New York and Washington.

“Time was short,” Mr. Sorensen remembered in an interview with The New York Times that was videotaped to accompany this obituary. “The hawks were rising. Kennedy could keep control of his own government, but one never knew whether the advocates of bombing and invasion might somehow gain the upper hand.”

Mr. Sorensen said, “I knew that any mistakes in my letter — anything that angered or soured Khrushchev — could result in the end of America, maybe the end of the world.”

The letter pressed for a peaceful solution. The Soviets withdrew the missiles. The world went on.

Theodore Chaikin Sorensen was born in Lincoln, Neb., on May 8, 1928 — Harry S. Truman’s 44th birthday, as he was fond of noting. He described himself as a distinct minority: “a Danish Russian Jewish Unitarian.” He was the son of Christian A. Sorensen, a lawyer, and Annis Chaikin, a social worker, pacifist and feminist. His father, a Republican who had named him after Teddy Roosevelt, ran for public office for the first time that year; he served as Nebraska’s attorney general from 1929 to 1933.

Lincoln, the state capital, was named for the 16th president. Near the Statehouse stood a statue of Abraham Lincoln and a slab with the full text of the Gettysburg Address. As a child, Mr. Sorensen read it over and over. The Capitol itself held engraved quotations; one he remembered was “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.”

Mr. Sorensen earned undergraduate and law degrees at the University of Nebraska and, on July 1, 1951, at the age of 23, he left Lincoln to seek his fortune in Washington. He knew no one. He had no appointments, phone numbers or contacts. Except for a hitchhiking trip to Texas, he had never left the Midwest. He had never had a cup of coffee or written a check.

Eighteen months later, after short stints as a junior government lawyer, he was hired by John F. Kennedy, the new Democratic senator from Massachusetts. Kennedy was “young, good-looking, glamorous, rich, a war hero, a Harvard graduate,” Mr. Sorensen recalled. The new hire was none of those, save young. They quickly found that they shared political ideals and values.

“When he first hired me,” Mr. Sorensen recalled, Kennedy said, “ ‘I want you to put together a legislative program for the economic revival of New England.’ ” Kennedy’s first three speeches on the Senate floor — late in the evening, when nobody was around — presented the program Mr. Sorensen proposed.

Kennedy made his mark with “Profiles in Courage,” published in January 1956. It was no great secret that Mr. Sorensen’s intellect was an integral part of the book. “I’ve tried to keep it a secret,” he said jokingly in his interview with The Times. But Mr. Sorensen drafted most of the chapters, and Kennedy paid him for his work. “I’m proud to say I played an important role,” Mr. Sorensen said.

He spent most of the next four years working to make his boss the president of the United States. “We traveled together to all 50 states,” Mr. Sorensen wrote in his book “Counselor: A Life at the Edge of History,” a memoir published in 2008, “most of them more than once, initially just the two of us.” There was no entourage until Kennedy won the Democratic nomination in 1960. It was not clear at the outset that he could do that, much less capture the White House.

“It was only after we had crisscrossed the country and began to build support at the grass roots, largely unrecognized in Washington, where Kennedy was dismissed as being too young, too Catholic, too little known, too inexperienced,” Mr. Sorensen said in the interview.