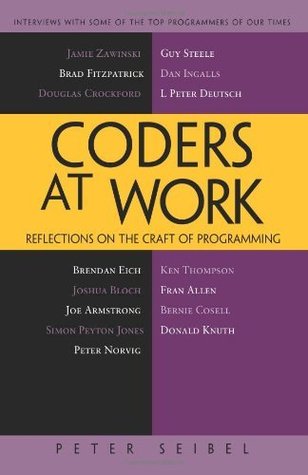

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Peter Seibel

Read between

April 2 - May 14, 2020

Deutsch: Yes, pure functional languages have a different set of problems, but they certainly cut through that Gordian knot. Every now and then I feel a temptation to design a programming language but then I just lie down until it goes away. But if I were to give in to that temptation, it would have a pretty fundamental cleavage between a functional part that talked only about values and had no concept of pointer and a different sphere of some kind that talked about patterns of sharing and reference and control.

But I feel like all of this is looking at the issue from a fairly low level. If there are going to be breakthroughs that make it either impossible or unnecessary to build catastrophes like Windows Vista, we will just need new ways of thinking about what programs are and how to put them together.

Deutsch: My PhD thesis was a 600-page Lisp program. I'm a very heavy-duty Lisp hacker from PDP-1 Lisp, Alto Lisp, Byte Lisp, and Interlisp. The reason I don't program in Lisp anymore: I can't stand the syntax. It's just a fact of life that syntax matters.

Seibel: Some people love Lisp syntax and some can't stand it. Why is that? Deutsch: Well, I can't speak for anyone else. But I can tell you why I don't want to work with Lisp syntax anymore. There are two reasons. Number one, and I alluded to this earlier, is that the older I've gotten, the more important it is to me that the density of information per square inch in front of my face is high. The density of information per square inch in infix languages is higher than in Lisp. Seibel: But almost all languages are, in fact, prefix, except for a small handful of arithmetic operators. Deutsch:

...more

Seibel: How do you design software? Do you scribble on graph paper or fire up a UML tool or just start coding? Thompson: Depends on how big it is. Most of the time, it sits in the back of my mind—nothing on paper—for a period of time and I'll concentrate on the hard parts. The easy parts just fade away—just write 'em down; they'll come right out of your fingertips when you're ready. But the hard parts I'll sit and let it germinate for a period of time, a month maybe. At some point pieces will start dropping out at the bottom and I can see the pyramid build up out of the pieces. When the

...more

Documenting is an art as fine as programming. It's rare I find documentation at the level I like. Usually it's much, much finer-grained than need be. It contains a bunch of irrelevancies and dangling references that assume knowledge not there. Documenting is very, very hard; it's time-consuming. To do it right, you've got to do it like programming. You've got to deconstruct it, put it together in nice ways, rewrite it when it's wrong. People don't do that.

Seibel: So some folks today would say, “Well, certainly assembly has all these opportunities to really corrupt memory through software bugs, but C is also more prone to that than some other languages.” You can get pointers off into la-la land and you can walk past the ends of arrays. You don't find that at all problematic? Thompson: No, you get around that with idioms in the language. Some people write fragile code and some people write very structurally sound code, and this is a condition of people. I think in almost any language you can write fragile code. My definition of fragile code is,

...more

Seibel: But there is a difference between a denial-of-service attack and an exploit where you get root and can then do whatever you want with the box. Thompson: But there are two ways to get root—one is to overflow a buffer and the other is to talk the program into doing something it shouldn't do. And most of them are the latter, not overflowing a buffer. You can become root without overflowing any buffers. So your argument's just not on. All you've got to do is talk su into giving you a shell—the paths are all there without any run-time errors. Seibel: OK. Leaving aside whether it results in

...more

Seibel: What was the relation between the design phase and the coding? You four got together and sorted out the interfaces between the parts. Did that all happen before your 17 programmers started writing code, or did the coding feed back into your design? Allen: It was pretty much happening as we went. Our constraints were set by the people we reported to. And the heads of the different pieces, like myself, reported to one person, George Grover, and he had worked out the bigger picture technically. And a lot of it was driven by the constraints of the customers. There was a lot of teamwork and

...more

Allen: Yes, I think he had the whole thing. But he replaced some of the software heads with people with hardware experience. And it was really the right thing to do because the hardware people already had a wonderful discipline around building hardware—the chip design and the testing process and all of that. And that was an older and much more rigorous ways of expressing designs. We software people were just making it up. Seibel: So you feel that, at least on that project, that they brought something to the software-development process that saved the project? Allen: It was absolutely

...more

Seibel: So sometimes—maybe even often—your people actually know what they're talking about and you shouldn't interfere too much because you might stomp out a good idea. It's trickier when you're really right and their idea really is a little bit flawed but you don't want to beat up on them too much. Allen: There was some of that. It was often where somebody came in with a knowledge of some area and wanted to apply that knowledge to an ongoing piece of project without having been embedded in the project long enough to know, and often up against a deadline. I ran into it big time doing some

...more

Seibel: Do you think C is a reasonable language if they had restricted its use to operating-system kernels? Allen: Oh, yeah. That would have been fine. And, in fact, you need to have something like that, something where experts can really fine-tune without big bottlenecks because those are key problems to solve. By 1960, we had a long list of amazing languages: Lisp, APL, Fortran, COBOL, Algol 60. These are higher-level than C. We have seriously regressed, since C developed. C has destroyed our ability to advance the state of the art in automatic optimization, automatic parallelization,

...more

But there was no real-time debugging. When the system crashed, basically the run light went out and that was it. You had control-panel switches where you could read and write memory. The only way to debug the system was to say, “What was the system doing when it crashed?” You don't get to run a program; you get to look at the table that kept track of what it was doing. So I got to look at memory, keeping track on pieces of graph paper what it was doing. And I got better at that. In retrospect, I got scarily better at that. So they had me have a pager. This was back in the era when pagers were

...more

I really believed that computers were deterministic, that you could understand what they were supposed to do, and that there was no excuse for computers not working, for things not functioning properly. In retrospect, I was surprisingly good at keeping the system running, putting in new code and having it not break the system. That was the first instance of something I got an undeserved reputation for. I know that my boss, and probably some other of my colleagues, have said I was a great debugger. And that's partly true. But there's a fake in there. Really what I was was a very careful

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

I really believed that computers were deterministic, that you could understand what they were supposed to do, and that there was no excuse for computers not working, for things not functioning properly. In retrospect, I was surprisingly good at keeping the system running, putting in new code and having it not break the system. That was the first instance of something I got an undeserved reputation for. I know that my boss, and probably some other of my colleagues, have said I was a great debugger. And that's partly true. But there's a fake in there. Really what I was was a very careful

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Cosell: I have to admit that I did both. I would make things simple in the large. But when I say that programs should be easy, it's not necessarily the case that specific pieces of the functionality of the program have to be easy. I could write some very complicated code to do the right thing, right there, code that people would cringe at and not be willing to touch. But it was always in an encapsulated place. Most of the bad programs I ran into, the ones where I threw things out and recoded them, there wasn't a little island of complexity you could try to understand and fix, but the

...more

So when they ask, “How long is it going to take you to put this change in?” you have three answers. The first is the absolute shortest way, changing the one line of code. The second answer is how long it would be using my simple rule of rewriting the subroutine as if you were not going to make that mistake. Then the third answer is how long if you fix that bug if you were actually writing this subroutine in the better version of the program. So you make your estimate someplace between those last two and then every time you get assigned a task you have a little bit of extra time available to

...more

Seibel: Have you heard of refactoring? Cosell: No, what is that? Seibel: What you just described. I think now there's perhaps a bit more acceptance, even among the project managers of this idea.

Seibel: Do you think that the nature of programming has changed as a consequence of the fact that we can't know how it all works anymore? Cosell: Oh, yeah. That's another thing that makes me a little bit more dinosaurlike. Everything builds assuming what came before. I remember on our old PDP-11, 7th edition Unix, we were doing some animation and graphics. That was a big deal. It was hard to program. The displays weren't handy. There were no libraries. Each generation of programmers gets farther and farther away from the low-level stuff and has fancier and fancier tools for doing things. The

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Now, why hasn't this spread over the whole world and why isn't everybody doing it? I'm not sure who it was who hit the nail on the head—I think it was Jon Bentley. Simplified it is like this: only two percent of the world's population is born to be super programmers. And only two percent of the population is born to be super writers. And Knuth is expecting everybody to be both. I don't think we're going to increase the total number of programmers in the world to more than two percent—I mean programmers who really resonate with the machine and that's their bread and butter that they've been

...more

Knuth: They were very weak, actually. It wasn't presented systematically and everything, but I thought they were pretty obvious. It was a different culture entirely. But the guy who said he was going to fire people, he wants programming to be something where everything is done in an inefficient way because it's supposed to fit into his idea of orderliness. He doesn't care if the program is good or not—as far as its speed and performance—he cares about that it satisfies other criteria, like any bloke can be able to maintain it. Well, people have lots of other funny ideas. People have this

...more

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

So there's that change and then there's the change that I'm really worried about: that the way a lot of programming goes today isn't any fun because it's just plugging in magic incantations—combine somebody else's software and start it up. It doesn't have much creativity. I'm worried that it's becoming too boring because you don't have a chance to do anything much new. Your kick comes out of seeing fun results coming out of the machine, but not the kind of kick that I always got by creating something new. The kick now is after you've done your boring work then all of the sudden you get a great

...more

Seibel: In 1974 you said that by 1984 we would have “Utopia 84,” the sort of perfect programming language, and it would supplant COBOL and Fortran, and you said then that there were indications that such language is very slowly taking shape. It's now a couple of decades since '84 and it doesn't seem like that's happened. Knuth: No. Seibel: Was that just youthful optimism? Knuth: I was thinking about Simula and trends in object-oriented programming when I wrote that, clearly. I think what happens is that every time a new language comes out it cleans up what's understood about the old languages

...more