More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

August 22 - August 24, 2019

just two weeks earlier, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin—he had been shot in the chest by a thirty-six-year-old New York bartender named John Schrank, a Bavarian immigrant who feared that Roosevelt’s run for a third term was an effort to establish a monarchy in the United States. Incredibly, Roosevelt’s heavy army overcoat and the folded fifty-page manuscript and steel spectacle-case he carried in his right breast pocket had saved his life, but the bullet had plunged some five inches deep, lodging near his rib cage. That night, whether out of an earnest desire to deliver his message or merely an

...more

“I know the American people,” he had said prophetically in 1910, upon returning to a hero’s welcome after an epic journey to Africa. “They have a way of erecting a triumphal arch, and after the Conquering Hero has passed beneath it he may expect to receive a shower of bricks on his back at any moment.” *

At 3:00 a.m. on February 14, Valentine’s Day, Martha Roosevelt, still a vibrant, dark-haired Southern belle at forty-six, died of typhoid fever. Eleven hours later, her daughter-in-law, Alice Lee Roosevelt, who had given birth to Theodore’s first child just two days before, succumbed to Bright’s disease, a kidney disorder. That night, in his diary, Roosevelt marked the date with a large black “X” and a single anguished entry: “The light has gone out of my life.”

“Of course a man has to take advantage of his opportunities, but the opportunities have to come,” he told an audience in Cambridge, England, in the spring of 1910. “If there is not the war, you don’t get the great general; if there is not the great occasion, you don’t get the great statesman; if Lincoln had lived in times of peace, no one would know his name now.”

In fact, at that time less was known about the interior of South America than about any other inhabited continent.

Roosevelt was an avid proponent of the Monroe Doctrine, and he had even attached his own imperialistic twist to it.

Edith was also worried about Roosevelt’s safety. He was no longer a young man, and he had driven his body too hard for too long. Worse, he had become secretive. She complained that Theodore had maintained a “sphinx-like silence” about his expedition into the Amazon. If he thought that his reticence might spare her worry, he was wrong. “I can but hope that the wild part of his trip is being more systematically arranged than is apparent,” she had written Kermit just a few weeks before they sailed.

John Hay, quickly understood that what his distinguished guest really wanted was an expedition that had much more potential for scientific discovery and historical resonance than the journey that Father Zahm had laid out for him. With a single question—startling for its simplicity in light of the series of events that it set in motion—Müller made Roosevelt an offer. “Colonel Roosevelt,” he asked, “why don’t you go down an unknown river?”

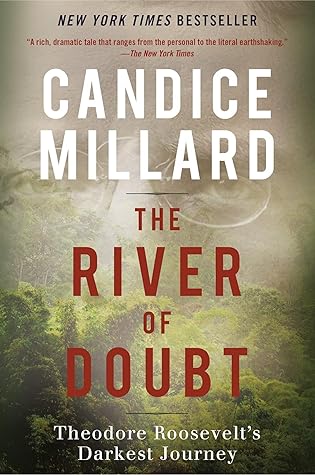

THE RIVER that Müller had in mind was one of the great remaining mysteries of the Brazilian wilderness. Absent from even the most accurate and detailed maps of South America, it was all but unknown to the outside world. In fact, the river was so remote and mysterious that its very name was a warning to would-be explorers: Rio da Dúvida, the River of Doubt.

Roosevelt’s admission that his new plan was “slightly more hazardous” than the original was, according to Frank Chapman, the understatement of the century. “In a word,” the bird curator later wrote, “it may be said with confidence . . . that in all South America there is not a more difficult or dangerous journey than that down the [River of Doubt].”

Drama was Roosevelt’s forte, and few subjects stirred him to greater emotion than did the Panama Canal.

Even for the most hardened, ambitious Brazilian frontiersmen, the territory that Roosevelt was preparing to cross was considered too difficult and dangerous to settle or explore. Indeed, except for indigenous tribesmen, only a handful of men in the history of Brazil had ever reached the headwaters of the River of Doubt and survived to tell the tale. Those men had been led by Cândido Rondon.

In the early twentieth century, modern maps of the Brazilian Highlands, drawn up by the world’s most respected and experienced cartographers, were strikingly wrong.

decade earlier, while he was campaigning in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Roosevelt’s carriage had been struck by a runaway trolley. One of his secret-service agents had been killed instantly, and he had been thrown thirty feet. The accident had left Roosevelt with loosened teeth, a swollen and bruised cheek, a black eye, and a severe injury to his left leg.

The expedition had now turned into a race against time. The survival of every man would depend on their collective ability to master the churning river, evade its ever-present dangers, and discover a route out of the deepest rain forest before their supplies ran out.

it represented a gamble of life-or-death proportions, because, from the moment the men of the expedition launched their boats, they would no longer be able to turn around. The river would carry them ever deeper into the rain forest, with whatever dangers that might entail. When they reached a series of rapids, they would have to portage around them—or mumble a prayer and plunge ahead. In either case, the option of returning the way they came was no longer available to them. They would find a way through, or they would perish in the attempt.

Father Zahm had certainly been the worst offender, but the comfort of all the Americans had always come first—even before the Brazilians’ basic needs. Unknown to Roosevelt, Rondon had not only ordered his men to eat less so that the Americans could eat more, but had intentionally overloaded the pack oxen and abandoned entire crates of the camaradas’ provisions in the hope that he would not have to ask the Americans to leave behind any of their ponderous baggage.

Even for Roosevelt, this trip, which was a rare opportunity for both adventure and achievement, was simply another trophy, one that he could keep next to his memories of his ranching days in the West, the Battle of San Juan Hill, and his seven years in the White House. If he survived, he would return as quickly as possible to the United States and the hectic political life that he had led before he had even set foot on South American soil.

The Amazon Basin gets as much as a hundred inches of rain each year, three times as much as New York City. The rain forest itself generates 60 percent of the precipitation through the transpiration process, and most of it falls during the months of March and April. The temperature was consistently high, usually in the mid-to-high eighties, but the heat was powerless to counteract the effects of the relentless rain. “There would be a heavy downpour,” Kermit wrote. “Then out would come the sun and we would be steamed dry, only to be drenched once more a half-hour later.”

It was the roar of a howler monkey, one of the loudest cries of any animal on earth. The sound, which can be heard from three miles away, is formed when the monkey forces air through its large, hollow hyoid bone, which sits between its lower jaw and voice box and anchors its tongue. The result is a deep, resonating howl that vibrates through the forest with strange, inhuman intensity, and echoes so pervasively that its location can be nearly impossible to identify.

So perfectly has the sloth adapted to its strange treetop life-style that its hair grows forward to allow the rain to drip effectively from its inverted body, and its sharp, curved claws are so specialized for the job of clinging to branches that the female cannot even pick up her young to carry them on her back—they must climb on by themselves after they are born.

“There were sufficient rations for the men to last about thirty-five days,” he wrote. “While the rations that had been arranged for the officials of the party would perhaps last fifty days.” With grim certainty, the officers calculated that, if the expedition continued to advance at this slow rate, they would be without food of any kind, beyond what they could catch or forage, for the last month of their journey.

There was no question that Rondon cared more for these dogs than he did for his own men, or that he worried about their safety and comfort. He showered them with affection, shared his food with them, and, on one occasion, even halted a march so that they could rest.

Although he rarely devoted more than a single sentence in his journal to the death of one of his men, Rondon penned heartfelt eulogies to his dogs.

Now retreat was impossible. In fact, in order to survive, they would have to go deeper into the territory of this unknown tribe—a land where, they now knew with certainty, they were not welcome.

BY ROUGHLY TWO MILLION years ago, humans had spread out of Africa and into Europe and Asia. Hundreds of thousands of years later, they migrated to Australia and New Guinea, which were then connected as a single continent. Because they did not yet have boats and could not endure the cruel cold of Siberia, tens of thousands of years more passed before they crossed the Bering Land Bridge and made their way into the Americas. When they finally began to populate North America, however, human beings quickly dispersed throughout the continent and, by crossing the Panamanian Land Bridge, soon reached

...more

RONDON’S CONCERN about the Indians did not mean that he agreed with the expedition’s forced march through the rain forest. He had faced unknown, unpredictable Indian tribes before, and if he was killed with an arrow or the entire expedition was massacred, he accepted that fate as the price of completing the work to which he had devoted his life. Roosevelt, on the other hand, was more determined than ever to finish their journey as quickly as possible, and was willing to make whatever sacrifices were necessary to minimize the dangers to the men, especially to Kermit. Under the strain of their

...more

man may be a pleasant companion when you always meet him clad in dry clothes, and certain of substantial meals at regulated intervals, but the same cheery individual may seem a very different person when you are both on half rations, eaten cold, and have been drenched for three days—sleeping from utter exhaustion, cramped and wet.”

Cherrie and Kermit’s greatest concern, however, was for Roosevelt. As devastating as it was for the other men, the idea of abandoning the canoes meant certain death for Roosevelt, and he knew it.

Roosevelt had never allowed himself to fear death, famously writing, “Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die.”

“I had always felt that if there were a serious war I wished to be in a position to explain to my children why I did take part in it, and not why I did not take part in it,” he had written in his autobiography just months before heading to South America.

Roosevelt’s friends, however, suspected that he wanted not only to fight in a war, but to die in one. “The truth is, he believes in war and wishes to be a Napoleon and to die on the battle field,” former President William Howard Taft had written of his estranged friend. “He has the spirit of the old berserkers.”

Before he even left New York, he had packed in his personal baggage, tucked in among his extra socks and eight pairs of eyeglasses, a small vial that contained a lethal dose of morphine. “I have always made it a practice on such trips to take a bottle of morphine with me. Because one never knows what is going to happen,” he told the journalist Oscar Davis. “I always meant that, if at any time death became inevitable, I would have it over with at once, without going through a long-drawn-out agony from which death was the only relief.”

Then, without a trace of self-pity or fear, Roosevelt informed his friend and his son of the conclusions he had reached. “Boys, I realize that some of us are not going to finish this journey. Cherrie, I want you and Kermit to go on. You can get out. I will stop here.”

Kermit met his father’s decision to take his own life with the same quiet strength and determination that the elder Roosevelt had so carefully cultivated and admired in him. This time, however, the result would be different. For the first time in his life, Kermit simply refused to honor his father’s wishes. Whatever it took, whatever the cost, he would not leave without Roosevelt.

Roosevelt realized that if he wanted to save Kermit’s life he would have to allow his son to save him. “It came to me, and I saw that if I did end it, that would only make it more sure that Kermit would not get out,” Roosevelt would later confide to a friend. “For I knew he would not abandon me, but would insist on bringing my body out, too. That, of course, would have been impossible. I knew his determination. So there was only one thing for me to do, and that was to come out myself.”

After finding Paishon, the four officers walked back to camp looking for Roosevelt. “When I met him,” Rondon later recalled, “he was very pent up.” “Julio has to be tracked, arrested and killed,” Roosevelt barked when he saw Rondon. “In Brazil, that is impossible,” Rondon answered. “When someone commits a crime, he is tried, not murdered.” Roosevelt was not convinced. “He who kills must die,” he said. “That’s the way it is in my country.”

When Henry Ford had introduced the Model T in 1908, the Amazon had been the world’s sole source of rubber. The wild popularity of these automobiles, and the seemingly insatiable demand for rubber that accompanied them, had ignited a frenzy in South America that rivaled the California gold rush. In The Sea and the Jungle, H. M. Tomlinson complained that the only thing Brazilians saw in their rich rain forests in 1910 was rubber.

for most Americans his death still seemed impossible. A man like Roosevelt could never die.

Rondon today remains one of Brazil’s greatest heroes, and his efforts on behalf of the Amazonian Indians have endured in the form of the modern Indian Protection Service—the National Indian Foundation, or FUNAI. In spite of all that he had tried to do for the Indians he loved, however, the inroads he made into their territory have had as devastating an impact on their survival as the rubber boom.