More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

Read between

October 18 - November 6, 2021

That night, whether out of an earnest desire to deliver his message or merely an egotist’s love of drama, Roosevelt had insisted on delivering his speech to a terrified and transfixed audience. His coat unbuttoned to reveal a bloodstained shirt, and his speech held high so that all could see the two sinister-looking holes made by the assailant’s bullet, Roosevelt had shouted, “It takes more than that to kill a bull moose!”

“Friends, perhaps once in a generation, perhaps not so often, there comes a chance for the people of a country to play their part wisely and fearlessly in some great battle of the age-long warfare for human rights.”

“We do not set greed against greed or hatred against hatred,” he thundered. “Our creed is one that bids us to be just to all, to feel sympathy for all, and to strive for an understanding of the needs of all. Our purpose is to smite down wrong.”

Perhaps even more striking than the peaks and valleys of Roosevelt’s life was the clear relationship between those extremes—the ex-president’s habit of seeking solace from heartbreak and frustration by striking out on even more difficult and unfamiliar terrain, and finding redemption by pushing himself to his outermost limits.

The impulse to defy hardship became a fundamental part of Roosevelt’s character, honed from earliest childhood.

Although it was Theodore’s own iron discipline that brought about this transformation, it was his father’s encouragement that sparked his resolve.

Finally, Theodore Sr. sat his son down and told him that he had the power to change his fate, but he would have to work hard to do it. “Theodore, you have the mind but you have not the body,” he said, “and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body. It is hard drudgery to make one’s body, but I know you will do it.”

After his father’s funeral, Roosevelt fought back. Upon finishing the school year, he fled to Oyster Bay to wrestle with his grief and anger in seclusion. In the small, heavily wooded village where his family had long spent their summers, he swam, hiked, hunted, and thundered through the forest on his horse Lightfoot, riding so hard that he nearly destroyed her. Then, before returning to Harvard, he disappeared into the Maine wilderness with an ursine backwoodsman named Bill Sewall. “Look out for Theodore,” a doctor traveling with Roosevelt advised Sewall. “He’s not strong, but he’s all grit.

...more

“Black care,” he explained, in a rare unguarded comment on the subject, “rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough.”

“Of course a man has to take advantage of his opportunities, but the opportunities have to come,” he told an audience in Cambridge, England, in the spring of 1910. “If there is not the war, you don’t get the great general; if there is not the great occasion, you don’t get the great statesman; if Lincoln had lived in times of peace, no one would know his name now.”

“The only question that gives me concern in connection with it is whether letting you take it will tend to unsettle you for your work afterwards. I should want you to make up your mind fully and deliberately that you would treat it just as you would a college course; enjoy it to the full; count it as so much to the good, and then when it was over turn in and buckle down to hard work; for without the hard work you certainly can not make a success of life.”

George Cherrie had spent the past quarter-century, more than half his life, collecting birds in South America. Although he had the lean, carved muscles of a jaguar and skin that looked as if it had been soaked in tannin and left to dry in the sun, Cherrie also had the refined features of a venerated statesman. His hair was closely clipped and graying, and he had a handsome face, a modest mustache, and a calm, dignified expression that unfailingly inspired trust and respect. If you were about to go into the Amazonian jungle, George Cherrie was the man you wanted by your side.

There was no cause for concern—so long as Roosevelt’s plans did not change.

Enunciated by President James Monroe in 1823, the doctrine sent a clear message to any European powers with colonial ambitions in South America that the United States would not stand idly by and allow the oppression, control, or colonization of any country in its hemisphere.

Whereas the Monroe Doctrine barred Europe from intervening in the affairs of any country in the Western Hemisphere, the Roosevelt Corollary asserted America’s right to intervene whenever it felt compelled.

A few weeks before his departure, Roosevelt had received a letter from former New York Congressman Lemuel Quigg—a longtime supporter of Roosevelt’s who had traveled through much of South America as a journalist—warning him that, if he planned to talk about the Monroe Doctrine on his trip, he could expect the political equivalent of being tarred, feathered, and ridden out of the continent on a rail.

The Mexican Revolution had been raging since 1910 and had already brought about the forced resignation and exile of one of the country’s presidents and the imprisonment and assassination of another.

Their grandfather, whom Roosevelt had idolized, had paid another man to fight for him during the Civil War, and Roosevelt had never gotten over it.

But Roosevelt could never understand what he saw as the one flaw in his father’s otherwise irreproachable character.

“I should regard it as an unspeakable disgrace if either of them failed to work hard at any honest occupation for his livelihood, while at the same time keeping himself in such trim that he would be able to perform a freeman’s duty and fight as efficiently as anyone if the need arose,”

Kermit had been the perfect companion in Africa, hardworking, uncomplaining, and independent,

“The ordinary traveller, who never goes off the beaten route and who on this beaten route is carried by others, without himself doing anything or risking anything, does not need to show much more initiative and intelligence than an express package,” Roosevelt sneered. “He does nothing; others do all the work, show all the forethought, take all the risk—and are entitled to all the credit. He and his valise are carried in practically the same fashion; and for each the achievement stands about on the same plane.”

With a single question—startling for its simplicity in light of the series of events that it set in motion—Müller made Roosevelt an offer. “Colonel Roosevelt,” he asked, “why don’t you go down an unknown river?”

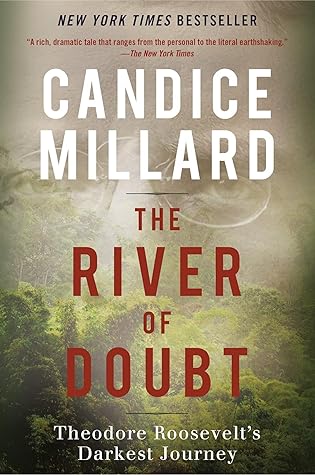

In fact, the river was so remote and mysterious that its very name was a warning to would-be explorers: Rio da Dúvida, the River of Doubt.

Rondon had stumbled upon its source five years earlier while on a telegraph line expedition in the Brazilian Highlands, the ancient plateau region south of the Amazon Basin, and he and his men had followed it just long enough to realize that they would need a separate expedition, one solely devoted to mapping its entire length, to know anything of substance about it.

Orellana, who had lost one of his eyes during the conquest of the Incas in Peru, plunged into the Amazon rain forest in 1541, in the hope of discovering the legendary kingdom of El Dorado,

The journey that Roosevelt had lightheartedly described as his “last chance to be a boy” had suddenly turned into his first chance to be something that he had always dreamed of being: an explorer.

“Tell Osborn I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know; I have had my full share, and if it is necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite ready to do so.”

Not everyone in South America admired Theodore Roosevelt, however, and he soon found that his detractors were as loud and passionate in their derision as his supporters were in their praise.

He wrote to his secretary of state, John Hay, that the United States should not allow the “lot of jackrabbits” in Colombia “to bar one of the future highways of civilization,” and he proceeded quietly to encourage and support a Panamanian revolution that had been bubbling under the surface for years.

“The human multitude, showing marked hostility, shouted with all their might vivas!—to Mexico and Colombia, and Down with the Yankee Imperialism!” a journalist for Lima’s West Coast Leader excitedly reported.

On the contrary, he took every opportunity to face down his attackers, ready to explain in no uncertain terms why he was right and they were wrong.

“The large auditorium in which he spoke seemed to be surcharged with electricity and everyone seemed to be prepared for a shock or an explosion. Everything—the environment, the speaker, the subject, the great historical event under review—was dramatic in the extreme, and everyone felt that it was dramatic.”

“I love peace, but it is because I love justice and not because I am afraid of war,” Roosevelt told the spellbound crowd. “I took the action I did in Panama because to have acted otherwise would have been both weak and wicked. I would have taken that action no matter what power had stood in the way. What I did was in the interest of all the world, and was particularly in the interests of Chile and of certain other South American countries. I was in accordance with the highest and strictest dictates of justice. If it were a matter to do over again, I would act precisely and exactly as I in very

...more

“I don’t remember a word I said tho’ I remember all I thought for I was with you the whole time,” he wrote her. “It just seems like a dream, dearest, and I get so afraid that I may wake, for if it’s a dream I want to stay asleep forever.”

“We would have both felt that I must go with father,” he wrote to Belle that night. “If I weren’t going I should always feel that when my chance had come to help, I had proved wanting, and all my life I would feel it.”

His determination to protect South American Indians and incorporate them into mainstream Brazilian society—a passion that would come to override all others in his life—grew less out of his ethnic background than his philosophical convictions. Rondon was a member of Brazil’s Positivist movement, which, founded by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in the mid-nineteenth century, had its foundations in the French Enlightenment and British Empiricism.

Largely a philosophy of humanity, Positivism chose scientific knowledge and observed facts over mysticism and blind faith, putting its trust in the inevitable pull of progress, a type of Darwinian evolution toward civilization.

the leaders of the Republic created a new flag for Brazil, choosing a green background with a bright-blue globe resting on a gold diamond. On the globe they scattered twenty-seven five-pointed stars, one for each of Brazil’s states and for the Federal District, and stretched a white banner across its face that today still proudly bears the Positivist motto: Ordem e Progresso, Order and Progress—not just for Brazilians but also for the country’s native inhabitants.

For Roosevelt, Rondon represented the kind of man he had championed and admired throughout his life: a disciplined officer who thrived on physical challenges and hardship, and accomplished great feats through sheer force of will. It would be a measure of his profound respect for Rondon that, years later, Roosevelt would count the Brazilian officer among the four greatest explorers of his time—alongside Roald Amundsen, Richard Byrd, and Robert Peary.

Although a military officer, Rondon approached his duties with a pacifist’s idealism that would ultimately secure him a place not merely as Brazil’s greatest explorer, but as one of its pioneering social thinkers.

Not only could Roosevelt withstand extreme tests of physical endurance, but he relished them—to the distress of anyone who was unfortunate enough to be along for the ride.

Their conversation often centered on the river toward which they were riding—its length, its character, where it would take them, and when they would reach its end. But the River of Doubt still seemed impossibly far away, and their past lives were ever present in vivid, and often disturbing, memories.

A cool man with a rifle, if he has mastered his weapon, need fear no foe.”

The trucks, which belonged to the Rondon Commission, each carried two tons of freight and had been outfitted with wide, slatted belts that wrapped around the wheels on each side like tank treads, forming what Miller referred to as an “endless trail” through the thick mud. This invention, which anticipated the use of the first military tank two years later, during World War I, amazed and elated the explorers. “It was a strange sight to see them racing across the uninhabited chapadão at a speed of thirty miles an hour,” Miller wrote. “Surely this was exploring de luxe.”

“We, however, did not share in our friend’s astonishment, inasmuch as we consider this and other differences as natural consequences of the methods adopted for the education of the Indians. . .. If we propose to educate men, so that they may incorporate themselves into our midst and become our co-citizens, we have nothing more to do than to persevere in applying the methods up to the present adopted in Brazil: if, however, our intention is to create servants of a restricted and special society, the best road to follow would be the one opened by the Jesuitic teachings.”

“The colonel’s Positivism was in very fact to him a religion of humanity,” Roosevelt wrote, “a creed which bade him be just and kindly and useful to his fellow men, to live his life bravely, and no less bravely to face death, without reference to what he believed, or did not believe, or to what the unknown hereafter might hold for him.”

Rondon’s brave and unyielding advocacy of the Amazonian Indian was to become his most important legacy—outshining even his achievements as an explorer.

Rondon believed that his mission in protecting and pacifying the Indians was larger than his own life, larger than any of their lives. He would rather die than surrender his ideals, and he obliged his men to follow suit.

Though Roosevelt had sympathy for the Indians and understood the injustices and cruelties that they had endured, in South America as well as in North America, Rondon’s passive, pacifist approach was alien to his entire way of thinking. He was much more inclined to conquer than to be slaughtered.