More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Laura Bates

Read between

August 1 - August 17, 2018

I did try to talk with a few of the inmates on B-East, but communication was all but impossible through those plexiglass partitions, and the inmates were too unfocused to comprehend, or to care about, anything Shakespearean.

I like to use the analogy that you’re way out in the middle of the ocean. You’re scared, panicking, desperate to do anything. You try swimming in one direction, you try another direction. You’re just desperate; that’s why you do desperate things and you overlook that it’s gonna make it worse. You see the potential for land, not thinking that it’s more sharks over there.”

Newton led a discussion of Hamlet’s observation that, to those who see it that way, all the world is a prison.

“This prison don’t matter,” Newton countered. “It’s not that you’re in prison. I’m sure it doesn’t help matters, but a lot of the guys here were in prison before they came here and they’ll still be in prison when they leave here.”

“They associate their misery to the fact that they’re in prison, and it’s not that. I think a lot of my misery was me hating me, and hating me made me hate everyone else.

I’m feeling stronger in my abilities every day, and the world just opens up. You really can do anything, you can shape your life any way you want it to be.

Prison is being entrapped by those self-destructive ways of thinking.”

For two years now, I had seen that Newton’s insights into prison and prisoners were of great value to the prison population. I started feeling that his insights into Shakespeare could be of value to the academic world as well.

I presented several professional papers on our work at national and international conferences. Some of these papers were published in collected volumes on Shakespeare studies.

I decided to share this work with my PhD dissertation director, Professor David Bevington. I considered him not only a great scholar, but also a great human being. He had traveled to a number of prisons in Chicago and Indiana to observe my work with Shakespeare and inmates, and he conducted guest lectures for my incarcerated students in the Indiana State University Correctional Education Program.

Newton’s enthusiasm for Shakespeare was becoming contagious throughout the prison population. “You can catch Shakespeare like a bad bug,” one prisoner told me, “and you just can’t shake it.”

In each case, the uneducated incarcerated reader was not intimidated by the idea of looking into Shakespeare. On the contrary, Newton put the reader at ease—and then always threw out those curveballs: his challenging, life-altering questions.

the nervousness undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that this conversation was being observed by the prison superintendent, the staff videographer, his Shakespeare professor and her husband, and Amy Scott-Douglass, an author of a book on studying Shakespeare in prison. Surrounded by these six people in this cramped space, he had to somehow focus his thoughts on the plays of Shakespeare.

“Did Shakespeare write King John after experiencing the death of a child of his own?” That was Newton’s opening question. “Because the grieving over the death of Arthur just seems so real, man.”

I was equally impressed with Bevington, who seemed perfectly at ease with this convicted killer sitting beside him, as they leaned close to each other to look at the Shakespeare book together.

“I felt like I could relate to Macbeth,” said Newton, “and I never exonerated him because of the influence of the witches. I mean, we all have influences.”

“But Julius Caesar has one my favorite freakin’ quotes,” he continued, quoting from memory: ‘So every bondman in his own hand bears the power to cancel his captivity.’ To me, that’s empowering, that we can free ourselves at any time—psychologically, I mean.”

With his dog-eared and annotated copy of The Complete Works of Shakespeare in front him, Newton was able to flip through the two thousand pages and find a particular quote he needed instantly, without even a pause in the conversation.

“‘There is no sure foundation set on blood, no certain life achieved by others’ death,’” he read from King John, act 4, scene 2. Then he slapped the book and added, “Exactly, exactly! That’s our life in here, man!”

“I think Henry the Fifth is my favorite play,” he said as they began to walk him out. “What a guy! I really want to be like him: strong, confident…honorable.”

“Amazing,” he said to me. I nodded. I knew it was unlike any Shakespearean dialogue he’d ever had at the university.

As we watched him disappear down the long corridor, walking on a leash between two officers and clutching his Shakespeare book with his hands cuffed behind his back, Professor Bevington turned to me and repeated, “He’s truly amazing.”

“I want to be the first prisoner in the state of Indiana to earn a PhD while incarcerated!”

“I’m pleased indeed to hear about Newton,” wrote Bevington. “I support the idea of his working toward the PhD. I do believe in him.”

It is the academic paradox: up or out. At any university, an assistant professor’s first six years must be followed by application for tenure.

Unfortunately, I was lacking in the required number of publications in peer-reviewed academic journals.

Committees don’t care. They don’t know prison; they know peer-reviewed academic publications—the more footnotes, the better. And here’s an irony: as a direct result of my work in prison, I was on probation myself.

“Shakespeare is my liberty,” he finished my sentence.

“You’re always railing against being treated like a subject, and now you’re turning me into a subject!”

Oh, great. I started envisioning a porno portrait of his middle-aged Shakespeare professor—sunbathing nude on the deck of a boat, perhaps—circulating among the prisoners in the segregation unit. They’ve been locked away for a long time, but are they really that desperate?

Newton was proud of telling me that she took on two jobs when his stepdad became ill and couldn’t work, because she never wanted to go on welfare. I respected her for that. (My mom had worked two jobs too.)

Her other two sons, one older than Newton and the other younger, turned out all right. One is a minister and the other is a police officer—at the same university in Muncie where Christopher J. Coyle had been killed.

In the summer of 2006, after more than ten years in isolation, Newton received word that he would finally be released into the general prison population.

“He’s changed a lot,” Harper said to me as his officers went to remove Newton from his cell. “If Shakespeare did that, then I’m impressed.”

I was happy to see him being released from his cage, sad to think what the loss of him would mean to the Shakespeare program.

It’d been three years since we met, but this was the first time we had sat down together alone, not in a group or at a cell door, but just sat together for a normal conversation—normal, that is, if you disregard the fact that one of us was sitting in a box and peering out through a little slot.

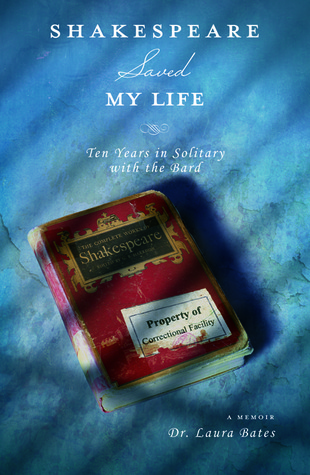

After I watched Newton disappear down the hallway, I took the folded paper out of my pocket. It was the survey. What has Shakespeare done for you? He had written, “Shakespeare saved my life.”

F-house! He was not sent to the other end of the state, after all; he was sent to the other side of the facility! Immediately, I requested permission for Newton to be admitted into the Shakespeare group in open population.

And I suggested that we use the time to create a workbook for the Shakespeare program that could be used in the SHU, which would present segregated prisoners with Newton’s insights and questions, even though he was no longer there in person. Even more remarkable, the manager obtained permission for me to meet with this hard-core prisoner—one just released after ten years in supermax—face-to-face, one-on-one, alone and unsupervised. Absolutely unprecedented.

Strangely, I felt the kind of anxiety that Newton had described feeling prior to the murder: “There is a point of no return,” he said, “when you have to fully commit to the deed.” That’s where I was now.

Harper picked up the phone, placed a call, then turned to me and said, “You’re all set.” As I walked away, he repeated, “He’s changed a lot.”

“How do we know when the killer dog can come into the house?” I had asked him. “You never do. It’s still a dog, it’s still got teeth, it can still bite. There’s no line that lets you know it’s a safe thing to do. But if you are the owner of the dog, you’ve developed a trust.” “Okay, so I’m the owner of this dog—” “That’s right. You are the owner of this dog. We have a relationship. You just know what you know—hopefully.

He was so self-conscious walking across the yard that he felt like everyone was looking at him, as if a spotlight was on him. It seemed like the longest walk ever! He told me that he felt “exposed and vulnerable”—and that when he entered the building and saw me, he felt “safe.”

I took his hand in mine, shook it, and, for the first time, called him by his first name. “Welcome to the world, Larry.”

And he reminds his readers that a wise man learns from others’ mistakes.

“Pronouns, Larry!” The English teacher in me reminded him to be more specific in his use of language. “What’s ‘this’ and what’s ‘that’?”

It is not our conscience that torments us over our image; that is our ego tormenting us. Our conscience torments us when we behave in ways that are contrary to our values.

When you look in the mirror and cringe as a result of your shame, it is conscience. When you look in the mirror and cringe as a result of how people think of you, it is ego. Which of the two is more prevalent in your life?

Larry’s job was working in the prison industries, making leather belts for the military. It was the first real job he’d ever had, and he proudly showed me his first check stub.

Hamlet is fighting the torment of what he could’ve done or should’ve done, or how he might have prevented the outcome. How many times have you laid there in bed fighting the torment of what you could’ve done, or should’ve done, or how you might have prevented the outcome?