More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Laura Bates

Read between

August 1 - August 17, 2018

I quickly learned, however, that a university education is not a prerequisite to reading Shakespeare. After all, his original audience was not college-educated. Neither was he.

I was not teaching them how to read and understand Shakespeare; they were teaching one another.

“This place is great!” Newton told me that day, gesticulating around his cell. “Great for reading Shakespeare!”

True, we grew up a generation apart, but there were a number of similarities in our childhood experiences. I grew up in an inner-city ghetto, as did Newton. I was white in a black neighborhood, as was Newton. I was a scrawny insecure kid, as was Newton.

Both Newton and I grew up on the streets, avoiding school much of the time—although we were both good students when we “applied” ourselves.

His hangout was the underpass of the highway; mine was the public restroom in back of the Shell gas station.

Criminal activity was common among his peers and mine: shoplifting, vandalism, drugs, and gang violence were part of everyday life during our elementary school years. My first boyfriend was gunned down in a drug deal gone bad. It could have been Newton who was teaching Shakespeare to me.

Newton’s childhood medical records include a history of untreated serious illnesses, injuries, and malnutrition.

“The one thing I remember,” he said, pointing at the entries, “is all these ‘missed medical appointments.’ ‘Follow-up not done.’ ‘Shots not up to date.’”

At the trial, when his attorneys tried to mitigate his guilt by describing his mother’s neglect, Newton sat with his fingers in his ears.

And then there was this one time, I’m too young to remember, but Mom says I was being babysat and these kids strapped me down to this ironing board and they were burning my arms with the iron. She pulls up and hears me screaming from outside the house. She says both my arms were all black.”

“Hospitalized me twice. Welfare took me out of the house. Said they wouldn’t let me back in unless he signed a paper promising not to beat me anymore. But here’s the thing: he refused to sign—and they put me back in anyway!”

I did start running away, then it was the bricks. I was free! That itself was addictive. It got to the point where even when I could defend myself and fight against him, I just wanted that life.

Muncie, Indiana, is the small Midwestern town in which Newton was born and raised, a working-class industrial city fallen on hard economic times. It was on the streets (the “bricks”) that he finally found the caring family that he never had at home.

We’d go back behind Kmart—their deli throws out a lot of food—and we’d get our food, the best food ever ’cause it was free, not just free of price, but free. As crazy and dumb as that sounds, I was free.”

At the start, my goal was simple and selfish: I wanted to learn from these convicted killers whether Shakespeare’s representation of murder is accurate. Whether it has verisimilitude, as they say in literary studies.

I was not only volunteering my time to this program, but I was also covering all my own expenses: reading materials, gas, a quick burger and fries munched on the road, and a bottle of vitaminwater that kept me going through the long evenings.

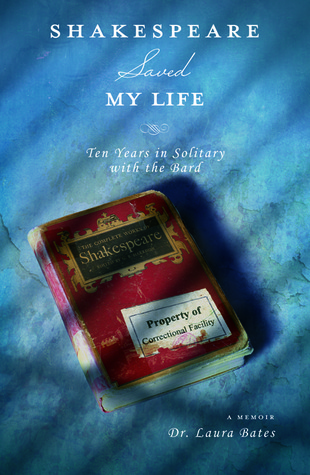

Two, some books were contraband in supermax. I could not give a segregated prisoner a hardbound book at all; it was considered a potential weapon.

From stealing ice cream to committing murder, Newton never acted alone. This was true from his earliest days. Like many kids do, Newton got involved in criminal activity at the urging of his buddies.

I started stealing with a neighborhood kid, I would have to say around age eight. The first thing I remember stealing was money out of my mom’s purse. I went to Kmart and bought Teddy Ruxpin; it had just come out. It was a bear that talked, and I thought that was the coolest thing.”

’Cause I remember him suggesting I wasn’t scared and how I felt with that, even though I was scared.”

“What was the impact of the first arrest?” “I mean, it made the wrong impression. I had status now. I was like, I been to Juvenile: ‘Give me rank, yeah!’ People looked at me different on the streets, like, ‘Aw, that’s Dink, man, he just got out of Juvenile!’”

Juvenile is not like some school or something. It’s nothing. You just sit in this big room and serve your little time, watch TV. Well, the other kids did. I didn’t.”

“‘Cabined, cribbed, confined’—like Macbeth says he feels. Or, maybe more like a coffin?”

“The program? Wow: full circle! It’s a small world, man.” I would find out just how small when a senior professor at the university approached me after my glowing report of Newton and his Shakespearean accomplishments to tell me that she recalled vividly the campus reaction to a murder of one of their students—the murder for which Newton was convicted.

I walked to the back of the room, turned a corner, and found it: the dark cell! Clearly, its original purpose had been as a storage closet, so there would have been no need for windows or ventilation. The thrift shop used it to store, ironically, used children’s toys. I found a beat-up little teddy bear, propped him up against the brick wall, and took his picture. He looked, I don’t know, scared.

My mother suffered a stroke just weeks after I started working at Indiana State University, and my meager part-time salary went entirely to covering her medical expenses.

The stressors about reaching that tenured position were directly related to my need to be able to support my parents.

My father’s world revolved entirely around caring for her. When she died, he moved into a small condominium and spent the next twelve years in one lonely little room surrounded by his books in boxes that he didn’t even bother to unpack. The man who had once been moved by the view from the Alps now didn’t even open the curtains to look out of the window.

“Everyone just puts themselves into so many prisons,” Newton had said, and it so aptly applied to my aging parents. I worried that it would apply to me as well.

Would I let childhood phobias become crippling paranoias? Literally or metaphorically, how long would I continue to miss out on my day at the beach because of my fear of boats?

As I would leave an institution, they would just place me in a grade. So I never really graduated from grade school. I remember being in middle school and looking at the material like Homer Simpson: duh! I was out within the week.

To this day, the sound of a semitrailer takes me back to the interruption of sleep. I just smile, because memories of any sort are my only freedoms, and even tough “freedoms” beat captivity!

I never studied Shakespeare in school. He was just a one-named figure from history to me, like Moses or Hitler. I had no idea that he wrote.

After just a few months, he had grown comfortable with the language. He likened it to solving math puzzles, something he enjoyed and was very good at.

That’s a Class A felony: strong-arm robbery. You take it physically, which usually entails you beating somebody, but I didn’t do anything like that.

Newton was living on the streets, robbing liquor stores, getting in and out of juvenile institutions, he did get a chance to make something of his life: he received an opportunity to join the Job Corps in Wisconsin. Instead, he ended up in prison for life.

The problem is when we look back, we don’t consider certain things. And that is that these two parts of the brain aren’t really connected—the part with the ‘I’m gonna get away’ and the other part ‘I’m in this life and gonna live this life.’

When I’m on the street, I’m not thinking about two weeks from now. I’m only thinking right now. I think for the great deal of troubled youth, it’s a common thing.”

I always wanted to be a father because I hated mine so much and I thought I would be a good father.”

It’s kinda strange, now I look at him, the circumstances of his life, that’s the way he viewed the world, his people probably beat him and that taught him that’s how you deal with disappointment, and in turn that taught me that’s how you deal when you get angry, you lash out. It’s just that earlier in my life, I hated him so much.”

As Mac killed Duncan, he was just in la la land! Even forgetting to leave the weapon! Man, that is just so authentic! The detail in fears, confusion, and gut-wrenching anxiety is uncanny! I regret to say that I have experience.

They had no one. They seemed to need me—or, at least, seemed to need Shakespeare. I realized that I couldn’t leave—not now, maybe not ever. In a way, I started to feel like I was serving a life sentence myself.

I remember that moment, the feeling of it, like, ‘Man, this is a life sentence. It’s not gonna heal itself.’ Because I must’ve felt through the whole process that things will work out, things just do.” He laughed. “But, yeah, you’re right. I must’ve had that hope somehow.”

I like nightmares. I like ones that you’re the most active in. I like waking up and having to look around the cell, even though I know there’s nothing there. I love those dreams, man!”

I was already in seg when it hit me: ‘Man, I got life in prison!’ All along I thought somebody was gonna fix it. It’s dumb and it’s my own fault. Obviously, they meant life in prison. But it never sunk in.

“I escaped from all them places,” he said. “Every one of them: Children’s Home. Youth Service Bureau. Juvenile Detention Center. Indiana Boys’ School. Two from each. Total of eight.”

Newton had actually starved himself to become small enough to fit into this opening.)

Newton had recently told me that few prisoners are motivated just by a desire to hurt people, that most “troubles” happen because of peer pressure, the need to look tough in front of others, something that is especially important in a tough prison environment.

I finished our conversation with a quote from Macbeth: “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow creeps in its petty pace to the last syllable of recorded time.”