More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Laura Bates

Read between

August 1 - August 17, 2018

Larry asked me, “Do you think that Shakespeare wrote King John after the death of his own child? The pain he describes just seems so real.”

Larry had clearly done a lot of reading, all the more remarkable considering he did not have access to books about Shakespeare, getting his insights instead from the Shakespearean texts themselves.

He says that he wants to be the first prisoner in the state of Indiana to earn a PhD while incarcerated. I have no doubts of his ability.

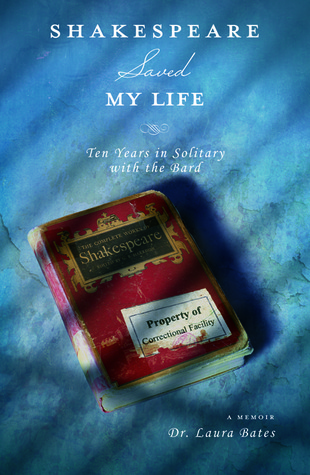

And then to be able to flip open the two-thousand-page Complete Works of Shakespeare and find the quote immediately: “When that this body did contain a spirit, a kingdom for it was too small a bound”!

Now we have received unprecedented permission to work together, alone, unsupervised, to create a series of Shakespeare workbooks for prisoners.

A record ten and a half consecutive years in solitary confinement, and he’s not crazy, he’s not dangerous—he’s reading Shakespeare. And maybe, just maybe, it is because he’s reading Shakespeare that he is not crazy, or dangerous.

Like war refugees, prisoners have lost everything: home, possessions, friends, and often family. For a prisoner, education has a special value as the one thing that no one can take from him.

Why is a prisoner’s motivation to earn a degree so that he can return to his family sooner viewed more negatively than a campus student’s motivation to earn a degree so he can make more money? And, two: What about the motivation of a prisoner, like Newton, who is serving a sentence of life with no possibility of parole?

Our final reading assignment was The Tragedy of Macbeth. It’s been a special piece of literature for me ever since I first read it at the age of ten. Well, I can’t really say that I “read” it at that age, but I did check it out of my elementary school library. And I can still recall the thrill of poring over its archaic words that I knew meant something significant, that I hoped would someday mean something to me.

Breaking into the state’s most secured unit would prove to be almost as difficult as breaking out. Neither one could be done legally.

As a middle-aged Shakespeare professor, I’m hardly an intimidating presence. But maybe I did need to convince myself that I was fearless. Maybe that was one of my reasons for teaching in prison.

Unfortunately, like almost everyone else I knew, my boss was not very supportive of my work in prison. He worried about my safety, and he also resented the hours that it took away from my day job.

My favorite Dave Matthews song came on the radio. “I will go in this way / and find my own way out,” Dave sang. Whatever might happen, I figured I would find my own way too.

In the twenty years I had spent working as a volunteer and as an instructor in minimum- and maximum-security prisons in Chicago and in Indiana, I had never met an inmate who scared me—until Newton.

Awareness of multiplicity of interpretation is the key to reading Shakespeare.

until you have been at peace, or content, with nothing…you cannot be pleased with anything. Or that you cannot be truly happy until you have come to terms with being nothing.

Now think of all the choices you make every day: what to wear, what to have for dinner, whom to call on the phone—these are choices Newton had not made in more than a decade.

During my SHU orientation days, I walked the ranges accompanied by Father Bob, the resident chaplain. With his long gray ponytail, his denim attire, and his laid-back demeanor, he reminded me of Willie Nelson (one of my husband’s favorite singers).

No volunteer had ever worked in this unit before, so there was no volunteer training program in place. Instead, I was required to complete the standard weeklong training program along with officers and other prison staff.

How to throw off an attacker (when I got home that evening, I practiced this move on my husband, a former college wrestling coach—and it worked!)

I quickly learned that it wasn’t the noisy ranges but the quiet ones—eerily quiet—that I needed to worry about.

Whenever I stepped onto a quiet range, I wondered whether everyone was sleeping, or medicated, or planning the next prison riot.

Volunteers never entered the SHU. Once they got to know me, they called out, “Shakespeare on the range!”

Because of Newton’s stabbing of Sgt. Harper (the only stabbing incident in the history of the SHU), the central administration in Indianapolis issued a mandate that everyone who worked in the SHU—officers, counselors, and, yes, even the Shakespeare professor—wear a bulletproof (i.e., knife-proof) vest.

(In my experience, male officers often cussed in the presence of a female visitor; prisoners rarely did so, and when they did, they usually apologized.)

I soon learned that the most popular reading material among SHU inmates was true-crime stories.

“You’ll never get these guys to talk about Shakespeare,” an inmate told me.

I have been studying how I may compare This prison where I live unto the world: And for because the world is populous And here is not a creature but myself, I cannot do it; yet I’ll hammer it out.

Thus play I in one person many people, And none contented: sometimes am I king; Then treasons make me wish myself a beggar, And so I am: then crushing penury

The day would include a group session in the specially designated wing where the prisoners would be brought and placed into individual cells, with me seated in the middle. But first, I had an individual session with Newton. He was not allowed to join the group. Given his history, he was considered to be too great of an escape risk.

I could tell only that he was not very big, not very tall, and dressed in white undershorts. It was not a sign of disrespect; it was the typical attire for segregated inmates—and why shouldn’t it be? Their cells were stifling hot, and they rarely, if ever, saw another human being.

With no natural light and an artificial light on twenty-four hours a day, segregated prisoners had no way of knowing if it was day or night. Surrounded by concrete, they didn’t even know whether it was winter or summer. When I arrived from the outside world, they never asked me about the weather. It didn’t matter in there.

“Fortune could be a reference to the classical idea of the Wheel of Fortune that determines man’s fate regardless of his actions,” he suggested. “It raises the dilemma of free choice versus predetermination.”

“Not that Wheel of Fortune, asshole!” Green shouted across the range. Then he muttered, “Freakin’ psych patients.

I found myself reflecting that I had never heard such an enthusiastic Shakespearean discussion in any college course I’d taken or taught.

here were a couple of prisoners locked away from the world, finding real-life meaning in Shakespeare’s four-hundred-year-old words. I thought my Shakespeare professors would be impressed. I thought Shakespeare would be impressed.

He was offended by the intrusion of Shakespeare into the wrestling match on his TV.

I couldn’t help beaming as I realized that on my very first day, I had already achieved what the prisoners themselves told me was impossible: I had gotten these guys to talk about Shakespeare!

With his hands and feet bound and a leather leash attached to his chains, he shuffled along, flanked by two officers, to the Shakespeare “classroom,” where he was again locked into an individual cell, placing his hands through the slot to be uncuffed.

Stunned to discover that long-term segregated prisoners still had a sense of humor, I found it hard to be annoyed with his constant quipping.

Surely, solitary confinement was the most absurd environment in which Shakespeare had ever been studied.

I had come to prison to teach prisoners about Shakespeare, but I would learn from them at least as much as I would teach to them.

When tigers start to pace, it’s taken the wild out of them. The psychological shift is happening. We do the same thing.

Everybody paces. And that’s what they’re all doing: playing out these fantasies in their head. You know, like old boy Richard.”

“Hey, you know what’s really cool? Here’s old boy Richard in this supermax, and he’s building a world inside of there with his thoughts. He’s trying to make his life mean something. And then here I am—it’s really cool how they mirror!—here I am, in that same little prison, trying to make my life mean something.”

(My husband liked the way Newton so often addressed me, a woman, with his common expression: “man.” Newton’s language was an eclectic mix of street slang and self-made intellectual.)

“Have you never met anyone who found his happiness in being the great killer?” “No, never.” He’d known more than his share of killers, so I accepted his statement as authority.

I would later learn that prisoners’ reading matter was quite eclectic. In segregation, it was largely determined by whatever was available to be circulated, illegally of course, from one prisoner to another.

But that is the beauty of Shakespeare: there often is more than one way of looking at the text, and I encouraged prisoners to do just that—and to respect one another’s interpretations. That lesson—how to look at things from more than one perspective—was precisely what they needed.

I found that the prisoners who had a genuine desire to read Shakespeare were able to do so, even though many of them had limited education and little, if any, previous experience with this literature.