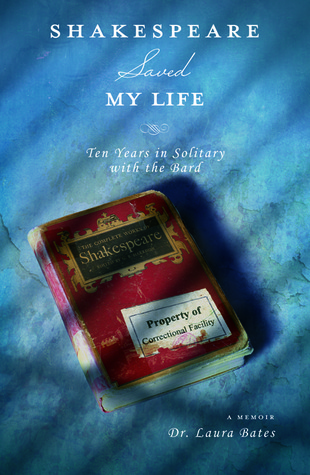

More on this book

Community

Kindle Notes & Highlights

by

Laura Bates

Read between

August 1 - August 17, 2018

We are all heroes in our own tragedies.

The “Tragical History” of a prisoner’s life seems to be one of many abuses, and therefore one with many justifications for revenge.

We relate to Hamlet because he is in the same kind of “prison of expectation.” His father has returned from the dead not to tell Hamlet how much he loved him, not to apologize for all the times that he worked late. He returned to make Hamlet revenge his death! It is that prison of expectation that we can relate to.

No matter what kind of social prison we are placed in, we are all empowered to make choices that are rooted in what we want, and not what others expect of us.

Our workbooks were being used by nearly one hundred students: approximately twenty in the SHU program and thirty in my Correctional Education capstone course in general population, plus close to fifty in my Shakespeare class on campus.

I enjoyed reading some of the best—and worst—responses to our considerations and asking Larry to guess whether they were written by a campus student or a prisoner in SHU or population. It was often hard to tell.

The idea is not to give them the answers, but to make themselves question.”

Larry usually did the same, but after ten years without access to Commissary (the prison’s mini-mart), the luxury was getting the better of him and junk food became his passion.

He spent a chunk of his weekly paycheck on Little Debbie cakes (the rest he sent home to Mom for his education fund). “Look at me,” he said between bites. “I’ve gained seventy pounds since I left the SHU!”

The Tragedy of Othello is the third of Shakespeare’s “criminal tragedies,” and it is an important...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Racial issues are especially sensitive and susceptible to misunderstanding in prison. At one prison I had visited before starting my own program, I was told that prisoners have threatened to kill one another over co...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.

Of all the experiences we go through, love is sometimes the most pleasurable, and sometimes it is the most painful. It is also one of the most used story lines of storytellers, and The Tragedy of Othello is no exception.

For a seasoned warrior, therapy for betrayal is most often violent. Othello is again no exception.

But the fact is, no one can make you be anything that is not already you, even if that you is buried deep inside, no?

If your mother was not forced to work away from home, she could have paid more attention to you and you might not have done such and such, but should your mother be in prison for what you have done? Who is responsible for what you do?

I had to ask myself what was motivating me in my deeds, and I came face-to-face with the realization that I was fake, that I was motivated by this need to impress those around me, that none of my choices were truly my own.

I’m of the opinion that we are the source of our misery; we perpetuate our own misery. And that realization is empowering! So Shakespeare saved my life, both literally and figuratively. He freed me, genuinely freed me.

“Hey,” he said. “Don’t get me all choked up. You’re gonna make me all sad and teary-eyed, and I’m a big strong convict.”

“I don’t think being dead worried me too much. Obviously, it must have somewhat. I can honestly say the one reason that I didn’t do it, and there may be other subconscious reasons, but the one reason is I kept picturing the impact on my loved ones. I was more worried about how they would take it. I didn’t want to hurt them anymore.”

I just really feel like I can go anywhere and do anything. I make decisions now ’cause I want to. Just the liberty in it, the freedom in it, that’s what makes me the happiest. So maybe that’s why I got choked up.”

I found myself wondering what his life would have been like had he been introduced to Shakespeare—or to a caring teaching on any subject matter—earlier in his life. There might have been one less man in prison—and one more man alive.

Their hostages were the teachers and other volunteers, some of whom were riding to the prison in the van with me. The incident had happened the previous Friday night.

In any case, on that night, when I could’ve been one of those teachers on the prison floor with a gun to her head, Shakespeare saved my life.

“but, hey, I also care about you and me. Most of these guys will be on the street one day, and when they move in next door to you or enroll in one of my classes on campus, I want them to be less violent than they were when they came to prison.”

If Shakespeare saves the life of a violent criminal, through rehabilitation, then he saves the life of potential future victims. At least, that’s the conviction that drove my work during my decade in supermax.

Another prisoner added that “most murders aren’t some passionately planned thing; most are just stupid circumstantial behaviors.”

“I believe,” Leonard continued, “as a convict having been allowed to interact with Shakespeare, that you and this program have allowed people to release anger, to release thoughts of revenge, various forms of frustrated thoughts or confusions.

And when you talk about the issue of murder, I believe that if an individual had a small alternative, a moment to think, a person to lean on, in that split second, it probably never would’ve happened.”

“Has Shakespeare saved a victim’s life?” I asked. “Yes. For sure, it’s saved one other person.” That was the answer I was hoping for. And it was echoed by another prisoner, who added: “At least two.”

Man, I’m set for life! That’s the good news. The bad news is, I’m doing life.

Because segregated prisoners could not come out of their cages to perform their scripts, I enlisted another group of prisoners from open population.

Dustin (our Macbeth) was sentenced to 199 years but reduced it to fifty. With time cuts and good behavior, he could be out before he reaches the age of fifty.

Greg (our resident singer-songwriter with a melodious and gentle voice) premeditatedly killed both of his parents, shooting them as they slept; he’ll be only thirty- five when he’s released.

Larry is, in fact, the only prisoner I’ve ever met who was convicted as a juvenile and is serving life without parole.

Through his good work in the Shakespeare program, in college, in other prison programs and job assignments, as well as in his acceptance of responsibility for his crime, Larry consistently demonstrated evidence of rehabilitation for nearly ten years. But every request for the right to appeal his sentence was denied. No matter what he does, he will never leave prison.

This prison that we’re in physically doesn’t matter. We were prisoners before we got here, and we’ll be prisoners when we leave here unless we realize that we’re fighting the wrong battle.

In the film, they speak directly to the teenage audience, telling them about the story of Romeo and Juliet and how it relates to them, trying to convince them to turn their lives around before it’s too late—before they end up with life in prison.

I’m the one who said that Shakespere was retarted and there was no point to it. But hearing it from you guys and not a boring teaher is making it a lot better.

Their self-image, insecurities, social icons—all that is not impacted, and that is the cancer!

Trust: that’s the key word in prison, and it’s not earned easily. And you never, ever ask anyone in prison to close his eyes. The fact that every one of them did was the strongest evidence I’ve ever had of how much they did, in fact, trust me.

After years without contact, Larry had reunited with his own family—mother, two brothers, countless nieces and nephews—thanks to Shakespeare.

Family visits are even more restrictive: the prisoner sits in a closed-circuit video booth while his relative sits in another booth in a different part of the prison.

Few prisoners have family members devoted enough to drive for hours to talk to their loved one through video.)

Now, with the cameras rolling and the audience watching, he held his script tightly in his shaking hands…and never even looked at it.

While most people spend their twenties trying to find their place in this world, I spent every single day of my twenties pacing my cell in isolation, trying to find reasons not to leave this world.

From somewhere in the audience, I could hear a gasp. I wondered if it was Larry’s mom. I wondered if she knew that he had been to that point in his life. He had told me that he had written a suicide letter—but did he send it?

“It was the right moment for me, so I said yes, I wanted to study Shakespeare. She left me a speech by King Richard the Second, which he was expressing from his own supermax dungeon four hundred years before. I just couldn’t believe that this guy was pacing around in his own dungeon, just like me. That was my first exposure to Shakespeare, and it would literally change the rest of my life.”

We’d try to define these terms like honor, integrity, etc. It really forced me to find some kind of substance to these terms that shape our lives. I was forced to look into a mirror, basically, at myself, to give these things real meaning.

I was literally digging into the very root of myself while digging into Shakespeare’s characters.

For instance, I couldn’t say that Hamlet’s impulse for revenge was honorable if I couldn’t tell you what honor is, and I couldn’t. I still can’t tell you what honor is, but I can tell you some of the thi...

This highlight has been truncated due to consecutive passage length restrictions.