Write What You Know

Write what you know . . . arguably the most important lesson in writing I ever learned! It was my mother who taught me this lesson. She did so when I was nine. How it came about is an interesting story (well, I think it’s interesting or I wouldn’t be telling it to you). But more than that, from an historical perspective, I think you might get a kick out of seeing the first eleven words of what was destined to be an 1100 word ‘opus’.

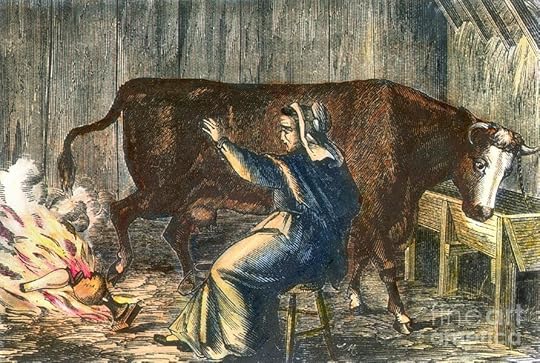

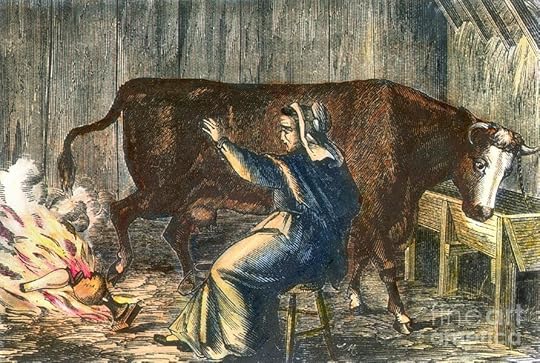

My story begins in 1871. No, that’s not the year of my birth…that came a few years later. But if you live in Chicago, have relatives who live in Chicago, or ever traveled to Chicago, you might recognize the scene below.

Yes, of course, it’s Catherine O’Leary and her infamous cow, the one who kicked over a lantern on October 8, 1871, starting a three-day conflagration that reduced the Windy City to ashes. Among other things, the city went ‘dry,’ which is to say, there wasn’t a drop of beer to be had within 100 miles.

But fear not. Into the breach stepped Joseph Schlitz. Now, this wasn’t the first time Mr. Schlitz had taken advantage of a tragedy. A lowly accountant at the August Krug Brewery in the 1850s, he was in the rather fortunate position of being in the right place at the right time when old man Krug departed this Earth in 1856. Within a few years, Schlitz changed both Krug’s widow’s name and the brewery’s name to his. It was in early October, 1871, then, that the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company started shipping beer to Chicago like it was going out of style. The result, of course, was, it made Milwaukee—and Schlitz—famous!

So it was that in 1944, just before the end of World War II, the Family Cohen found itself in Milwaukee. By 1947, at age nine, we were living near 17th and Lloyd Streets on Milwaukee’s West Side, where my younger brother and I attended the Lloyd Street Elementary School. The school was located about one-half mile from the house. We left each weekday for classes at exactly '9-9'—quarter to nine in the morning—with me responsible for getting my brother to school (and, of course, home again). This was necessitated by the fact my father had already left for work while my mother was busy with my baby sister.

Having to shepherd my brother to and from school didn’t leave much time to explore the neighborhood in the morning, of course, so days on which he stayed home for one reason or another were to be coveted. Why? Because on those days, it meant by leaving slightly earlier, I was free, for example, to stop at Pete’s Tavern, which was located a block from the house. My intent was always to learn whether or not he had any empty cigar boxes into which I could put my ‘stuff'…baseball cards, marbles, a stray ball and jack, my Duncan Yo-Yo, chalk...whathaveyou! Stuff!

What? You’re surprised a nine-year-old could boldly walk into a tavern on his way to school without anyone batting an eye. Hey! This was Milwaukee!! And this wasn’t the only tavern on my route to school, by the way. Sooner or later I hit them all during the school year.

And when I left Pete’s, say, I’d move on to the back of the slaughterhouse down the street where, after climbing the back stairs, it was possible by peering into the windows to determine whether cattle or sheep were being processed on any given day.

Frankly, on the days I was alone, it’s a wonder I made it to school at all.

But it was after school that the real fun began. By accident one day I found a garage in an alley several blocks from my house that contained a stable with four ponies. Shetland mares all, they were owned by the father of a boy who became a good friend of mine. His name was Stefan. His father used to give children rides on Sundays at local parks on the north and west sides of the city. The ponies fascinated me, and I never passed up an opportunity to sneak over to visit them and Stefan after school before running home to practice the piano. Occasionally, when no one else was around, Stefan would let me sit on one of the gentler ones, easily distinguished from the others by her shiny black coat and a white star under her forelock.

“Come on, Stefan, let’s play some stickball in the alley before I have to go home,” I’d often would call after school when I got within earshot of the little stable.

“Can’t, Teddy,” was Stefan’s forlorn reply more often than not. “Must do stable.” Stefan did not speak English well. His family, like several others in his neighborhood, immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe following World War II with the help of the Roman Catholic Church. Still, he and his little sister, Kasienka, were the only two in their family who spoke much English, and only then because of having attended public school. His father, a janitor, worked at two jobs during the week while his mother cleaned houses for women on Milwaukee’s east side. Stefan and Kasienka attended Brown Street Grade School, so at least during the day, their parents did not have to worry about them. But after school, it was Stefan’s job to muck out the stable as soon as he got home.

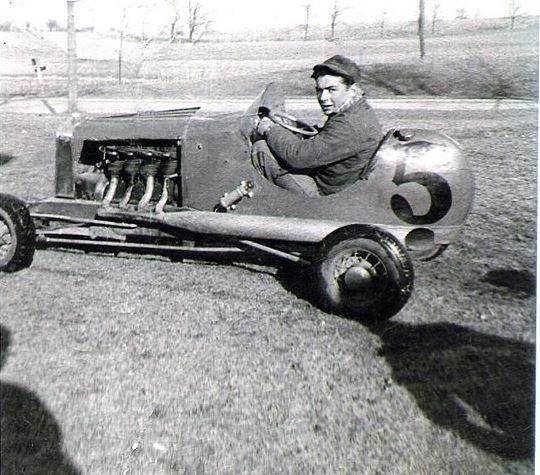

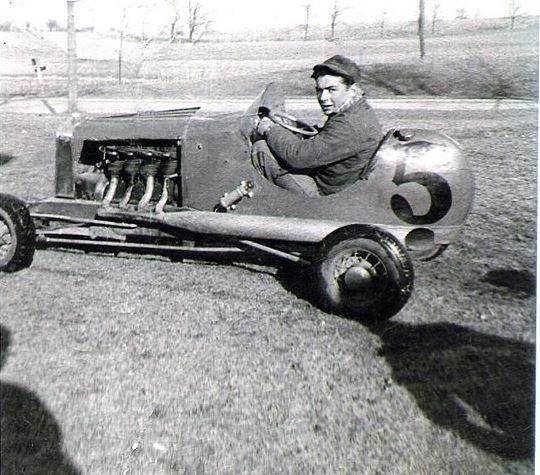

The alley behind our house was quite interesting as well. Among other attractions was a man who garaged his midget racer several garages to the north of where my father stored his Packard.

And not too much farther up the alley was where Old Ned was stabled.

Remember, the war had only ended two years earlier…the American truck and automobile industries were still getting back on their feet. In Milwaukee, horses still were used to help deliver milk, pull trash and garbage wagons, pull snow plows, and even deliver ice (yes, not everyone had an electric refrigerator in 1947).

But back to my writing lesson and to the incident that triggered my first introduction to prose, as it were. Enter ‘Jimmy’.

Anyone who knows dogs will recognize this little guy as a rat terrier. I knew two of them. Jimmy and his partner used to come down our alley every evening just after the sun set with their owner, a grizzled old man with five-days stubble on his face. Carrying a long stick, he would poke around the garbage cans in the alley, the intent being to scare rats into the open for Jimmy and his partner to dispatch. For me it was great sport just to walk with them. And so, whenever possible, while my father was at work and my mother was busy with my younger brother and sister, I snuck out to walk the alley with Jimmy & Company.

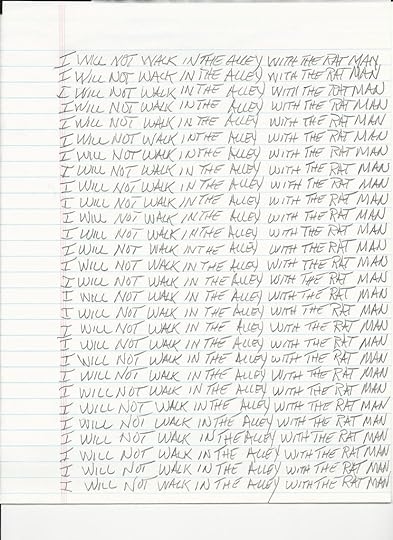

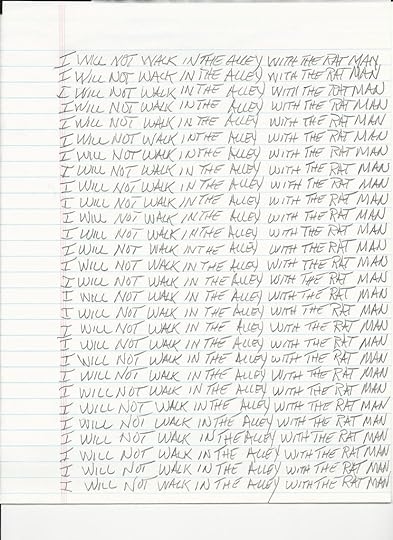

Until one night I got caught. And therein hangs the tale of my first lesson in writing from my mother. It comprised writing eleven words one-hundred times each, in order, before I would be allowed to play outside again after school. Here's the first page of my tome:

Despite getting dispensation to listen to 'The Lone Ranger' on the radio while serving my sentence, this exercise, excruciating as it was, demonstrated unequivocally how important it is to write about the things you know. It’s a lesson I’ve never forgotten and is something you might want to keep in mind as you sit down to write your Great American Novel.

My story begins in 1871. No, that’s not the year of my birth…that came a few years later. But if you live in Chicago, have relatives who live in Chicago, or ever traveled to Chicago, you might recognize the scene below.

Yes, of course, it’s Catherine O’Leary and her infamous cow, the one who kicked over a lantern on October 8, 1871, starting a three-day conflagration that reduced the Windy City to ashes. Among other things, the city went ‘dry,’ which is to say, there wasn’t a drop of beer to be had within 100 miles.

But fear not. Into the breach stepped Joseph Schlitz. Now, this wasn’t the first time Mr. Schlitz had taken advantage of a tragedy. A lowly accountant at the August Krug Brewery in the 1850s, he was in the rather fortunate position of being in the right place at the right time when old man Krug departed this Earth in 1856. Within a few years, Schlitz changed both Krug’s widow’s name and the brewery’s name to his. It was in early October, 1871, then, that the Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company started shipping beer to Chicago like it was going out of style. The result, of course, was, it made Milwaukee—and Schlitz—famous!

So it was that in 1944, just before the end of World War II, the Family Cohen found itself in Milwaukee. By 1947, at age nine, we were living near 17th and Lloyd Streets on Milwaukee’s West Side, where my younger brother and I attended the Lloyd Street Elementary School. The school was located about one-half mile from the house. We left each weekday for classes at exactly '9-9'—quarter to nine in the morning—with me responsible for getting my brother to school (and, of course, home again). This was necessitated by the fact my father had already left for work while my mother was busy with my baby sister.

Having to shepherd my brother to and from school didn’t leave much time to explore the neighborhood in the morning, of course, so days on which he stayed home for one reason or another were to be coveted. Why? Because on those days, it meant by leaving slightly earlier, I was free, for example, to stop at Pete’s Tavern, which was located a block from the house. My intent was always to learn whether or not he had any empty cigar boxes into which I could put my ‘stuff'…baseball cards, marbles, a stray ball and jack, my Duncan Yo-Yo, chalk...whathaveyou! Stuff!

What? You’re surprised a nine-year-old could boldly walk into a tavern on his way to school without anyone batting an eye. Hey! This was Milwaukee!! And this wasn’t the only tavern on my route to school, by the way. Sooner or later I hit them all during the school year.

And when I left Pete’s, say, I’d move on to the back of the slaughterhouse down the street where, after climbing the back stairs, it was possible by peering into the windows to determine whether cattle or sheep were being processed on any given day.

Frankly, on the days I was alone, it’s a wonder I made it to school at all.

But it was after school that the real fun began. By accident one day I found a garage in an alley several blocks from my house that contained a stable with four ponies. Shetland mares all, they were owned by the father of a boy who became a good friend of mine. His name was Stefan. His father used to give children rides on Sundays at local parks on the north and west sides of the city. The ponies fascinated me, and I never passed up an opportunity to sneak over to visit them and Stefan after school before running home to practice the piano. Occasionally, when no one else was around, Stefan would let me sit on one of the gentler ones, easily distinguished from the others by her shiny black coat and a white star under her forelock.

“Come on, Stefan, let’s play some stickball in the alley before I have to go home,” I’d often would call after school when I got within earshot of the little stable.

“Can’t, Teddy,” was Stefan’s forlorn reply more often than not. “Must do stable.” Stefan did not speak English well. His family, like several others in his neighborhood, immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe following World War II with the help of the Roman Catholic Church. Still, he and his little sister, Kasienka, were the only two in their family who spoke much English, and only then because of having attended public school. His father, a janitor, worked at two jobs during the week while his mother cleaned houses for women on Milwaukee’s east side. Stefan and Kasienka attended Brown Street Grade School, so at least during the day, their parents did not have to worry about them. But after school, it was Stefan’s job to muck out the stable as soon as he got home.

The alley behind our house was quite interesting as well. Among other attractions was a man who garaged his midget racer several garages to the north of where my father stored his Packard.

And not too much farther up the alley was where Old Ned was stabled.

Remember, the war had only ended two years earlier…the American truck and automobile industries were still getting back on their feet. In Milwaukee, horses still were used to help deliver milk, pull trash and garbage wagons, pull snow plows, and even deliver ice (yes, not everyone had an electric refrigerator in 1947).

But back to my writing lesson and to the incident that triggered my first introduction to prose, as it were. Enter ‘Jimmy’.

Anyone who knows dogs will recognize this little guy as a rat terrier. I knew two of them. Jimmy and his partner used to come down our alley every evening just after the sun set with their owner, a grizzled old man with five-days stubble on his face. Carrying a long stick, he would poke around the garbage cans in the alley, the intent being to scare rats into the open for Jimmy and his partner to dispatch. For me it was great sport just to walk with them. And so, whenever possible, while my father was at work and my mother was busy with my younger brother and sister, I snuck out to walk the alley with Jimmy & Company.

Until one night I got caught. And therein hangs the tale of my first lesson in writing from my mother. It comprised writing eleven words one-hundred times each, in order, before I would be allowed to play outside again after school. Here's the first page of my tome:

Despite getting dispensation to listen to 'The Lone Ranger' on the radio while serving my sentence, this exercise, excruciating as it was, demonstrated unequivocally how important it is to write about the things you know. It’s a lesson I’ve never forgotten and is something you might want to keep in mind as you sit down to write your Great American Novel.

Published on May 15, 2015 08:34

•

Tags:

autobiography, lessons_learned, milwaukee, writing

No comments have been added yet.