Korean History as Told Through Objects

An hour’s drive south of Seoul’s center, in Seongnam City, the photographer Bohnchang Koo occupies two small buildings resting on a verdant hillside. Designed by an architect friend twenty-five years ago, the airy buildings serve as Koo’s living space, studio, and home for a sprawling, eclectic collection. Ceramic vessels sit atop bookshelves, a decorative paper lantern in the shape of a lotus flower hangs from the ceiling, a rusted cash register proudly presents itself as an objet trouvé, and ancient wooden doors from the late Joseon dynasty enjoy a new life as window shutters. Under a vitrine is a recent acquisition: a thousand-year-old figure from Inner Mongolia, part human, part animal. “I could feel the touch of the craftsman who made it,” Koo tells me, recalling what attracted him to the curious form when he came across it at a local antique shop. His chockablock but orderly interiors have the feel of a well-selected antiques market—or the back room of a museum—and are the inevitable domain of an artist who chronicles how histories are revealed through talismanic objects.

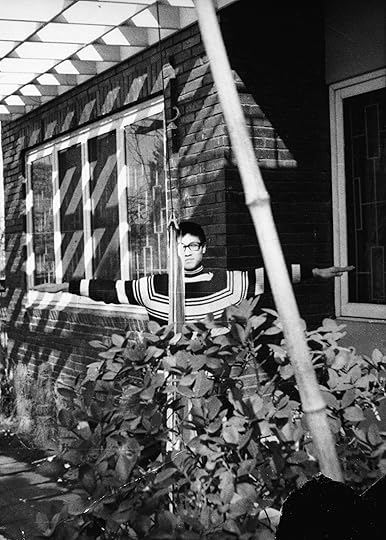

Bohnchang Koo, Self-portrait, 1968

Bohnchang Koo, Self-portrait, 1968Koo, a slim, gregarious man in his early seventies, traces his impulse to observe and collect to his childhood. The self-described shy one in a family of six children, his introversion drew him to become a diligent gleaner while growing up in Seoul, excavating shards of porcelain, pocketing peculiar rocks, pieces of colored paper, boxes, and other street detritus. He would assemble small collections of castaway treasure only to have his mother, concerned about space in the crowded family home, toss them into the trash bin. One acquisition, though, points to when his twin arts of collecting and photography first became intertwined. A 1964 brochure for the Tokyo Olympic Games—acquired by his father, who frequently traveled for his job in the textile industry—made an early impression about the allure of visual storytelling and, perhaps, Korea’s fraught relationship with its nearby island neighbor.

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

Aperture Magazine Subscription 0.00 Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

[image error]

[image error]

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription $ 0.00 –1+ View cart DescriptionSubscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Although Koo studied business administration at Yonsei University, in Korea, he moved to Germany in 1979 to pursue art at the Hamburg Fachhochschule für Gestaltung (University of Applied Sciences for Design). He thought he might become a painter, maybe a graphic designer. A life as a photographer hadn’t yet occurred to him, nor had the idea that anyone might pursue this as an occupation. Even so, he picked up the camera and began capturing, in both color and black and white, the abstracted textures of European cities. His professors, in response, encouraged him to bring more of himself, his own background and subjectivity, into the work. When he returned to Seoul in 1985, having encountered the work of Joseph Beuys, Irving Penn, Josef Sudek, and others, he embarked on projects that rejected the then-dominant style of social documentary. He experimented with photograms, Polaroids, and photo collage, stitching images together into elaborate tactile patchworks that emphasized the physicality of images and their capacity for personal expression.

In 1988, he organized an exhibition at Seoul’s Walker Hill Art Center titled The New Wave of Photography, participating as one of the artists. “It was considered a decisive turning point in the history of Korean photography,” said Hee Jean Han, curator at the Photography Seoul Museum of Art, who recently organized a retrospective of Koo’s work and credits him with fostering experimentation in the Korean photography scene. “Amid the politically repressive 1980s under Korea’s military dictatorship and the rapidly transforming city of Seoul, Koo’s personal feelings of anxiety and alienation became a catalyst for his exploration of self and society. It was ultimately a journey that established him as a pioneer bridging photography and contemporary art in Korea,” Han explained. Although Koo only taught for around two years at Kaywon University of Art & Design, his expanded notion of photography would serve as a model for younger generations.

Bohnchang Koo’s studio, Seoul, 2025

Bohnchang Koo’s studio, Seoul, 2025  Bohnchang Koo, Yeouido Hangang Park, Seoul, ca. 1985

Bohnchang Koo, Yeouido Hangang Park, Seoul, ca. 1985 Koo’s penchant for formal experimentation, however, didn’t mark a complete abandonment of an observational way of working. He made a body of work on Seoul, rendered in saturated color, around the time of the 1988 Olympic Games. The city’s multibillion-dollar civic project saw the construction of new highways, subways, stadiums, and the cleanup of the Han River. This was an era also marked by political change and street protests, as the country evolved from dictatorship to democracy. Koo’s read of urban space in this transitional time, despite the punchy Ektachrome and Kodachrome colors, is melancholic. Six years abroad afforded critical distance. Missing the calm gray days in Germany, all he saw was color, sometimes in garish expressions. Picnickers find refuge on a solitary patch of green grass in an expanse of dirt; a family poses in front of the river with a partly constructed bridge in the background; pedestrians pass under a monolithic elevated highway; a rack of women’s shoes is left abandoned. The air of optimism is deflated by an undercurrent of uncertainty. Koo recalls this period in Seoul as one of change and chaos; it was not uncommon to hear tear gas being fired onto the streets somewhere off in the distance.

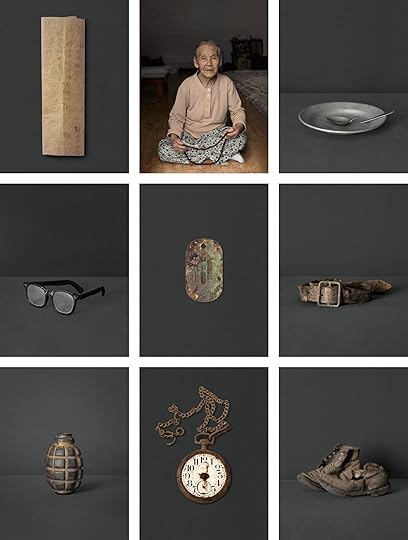

South Korea would chart a future of economic ascent, realized in the ubiquitous clusters of high-rises that today dominate Seoul’s skyline. As his city transformed into shimmering glass and steel, Koo began to look closely at what older surfaces transmitted, seeking trapdoors to the metaphysical in the everyday. A series on his terminally ill father, Breath (1995), a kind of memento mori, homes in on textures and details: his father’s leathery skin, a stopped pocket watch, a decaying bird—among inky images of nature suggestive of temporal ebb and flow.

Bohnchang Koo, Concrete Gwanghwamun 01, 2010

Bohnchang Koo, Concrete Gwanghwamun 01, 2010  Bohnchang Koo, Horse Riding Kkokdu 02, 1998, from the collection of the Ockrang Cultural Foundation, Seoul

Bohnchang Koo, Horse Riding Kkokdu 02, 1998, from the collection of the Ockrang Cultural Foundation, Seoul Koo continued to shift toward still life, isolating objects he viewed as messengers from the past. After encountering, in the late 1980s, a photograph of the Austrian Anglo ceramicist Lucie Rie posing with a Korean moon jar, he became preoccupied with ceramics, especially white porcelain, as conduits of history. “The vessel seemed to me as if it was waiting to be rescued and yearning for its hometown,” he said. Years later, an encounter in a Japanese women’s magazine with images of Joseon dynasty– era porcelains inspired a similar feeling. Why were these pieces so far from home, residing in collections abroad? Koo began to seek out and photograph vessels displaced from Korea in museum collections in Japan, Europe, and the United States. In 2006, he photographed the moon jar, now held in the British Museum, in London, with which Rie had posed. Widely exhibited and published, his photographs would popularize white ceramics that had previously been overlooked as pedestrian, fueling a revival of interest among artists and collectors.

Bohnchang Koo, Gobdol JM-GD 14-2, 2006, from the collection of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum

Bohnchang Koo, Gobdol JM-GD 14-2, 2006, from the collection of the Japan Folk Crafts Museum  Bohnchang Koo, Vessel OSK 22-2, 2005, from the collection of the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka

Bohnchang Koo, Vessel OSK 22-2, 2005, from the collection of the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka In the recently collected compendium of essays The Beauty of Everyday Things, the Japanese art historian and poet Soetsu Yanagi, a leading thinker behind the mingei (often translated as “arts for common people”) movement, praises humble everyday objects made by anonymous producers for their marriage of aesthetics and functionality. Yanagi founded the Korean Folk Art Museum in Seoul in 1924, and the Japan Folk Crafts Museum in Tokyo in 1936. His essays ponder and celebrate the aura of patina, pattern, embroidery, and clay, invoking Zen expressions such as “the inelegant is also the elegant.” In 1920, in response to Japan’s ongoing occupation of Korea, which began in 1910 and lasted for thirty-five years, and its repression of the March First Movement in 1919, he penned “A Letter to My Korean Friends,” an earnest, heartbroken apology in epistolary form, which appeared, albeit as a censored version, in the Japanese magazine Kaizo. Among his calls for spiritual and cultural common ground to resist a cult of imperial conquest, Yanagi praised the character of Korean ceramics of the Goryeo Kingdom (918–1392) and the utilitarian forms of the Joseon era (1392–1897), describing them as “sorrowful objects” of the everyday that offered comfort. (His conflation of Korean ceramics and “sorrow” would later be critiqued as a colonial read.) For Yanagi, the form of an object was imbued with meaning. “It is line,” he wrote, in reference to Korean porcelain, “that vividly chronicles the pathos of life and the trials and tribulations of history.”

Installation view of Koo Bohnchang: Look of Things, 2024, at the National Asian Culture Center, Gwangju, South Korea

Installation view of Koo Bohnchang: Look of Things, 2024, at the National Asian Culture Center, Gwangju, South KoreaThis observation might be applied to Koo’s photography. He became interested in Yanagi’s writing in the early aughts and appreciated how he had praised less ornate Korean ceramic traditions that were superseded by celadon porcelain, revered for its lustrous green glazes. However, Koo’s interest exceeds aesthetic appreciation. He sees his still lifes, or portraits, of vessels as a reclamation effort, a way of bringing these works back together, “a reunion through photographs.” These frontal, shadowless images, photographed against rice paper and printed large-scale, monumentalize the delicate forms. They appear vividly charged, leaning toward abstraction with the otherworldly presence of a Constantin Brancusi sculpture and the softness of a Giorgio Morandi painting. The curator Alejandro Castellote has observed that “several types of aura overlap in this series: the aura of beauty, the aura of polyphony emanating from its minimalist forms, the aura of Taoist spirituality, the aura that pertains to the assertion of Korean cultural identity, and the aura of coloniality.”

Bohnchang Koo, Mask Gangneung Gwanno 03-2, 2002

Bohnchang Koo, Mask Gangneung Gwanno 03-2, 2002  Bohnchang Koo, DMZ, 2010

Bohnchang Koo, DMZ, 2010All works courtesy the artist

Koo acknowledges the politics at play in his work. “I chased the collections of the most important museums in Japan,” he said. “As an artist, I am proud that I have brought their images and spirits into my negatives. Not using weapons, like guns and swords, but with my camera.” He would chase objects close to home as well. A 2010 series on the Gwanghwamun Gate of the sprawling landmark Gyeongbokgung Palace, originally built in 1395, shows the broken remains, propped with metal beams, of an ornately decorated structure that has been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times over the centuries due to fires, wars, and colonial dictates. The sections photographed by Koo are from the 1960s reconstruction, after the gate was destroyed during the Korean War. A series called DMZ (2010) is less ambiguous, looking, with forensic precision, at the legacy of the war through items at the War Memorial of Korea. Other series, on traditions of mask making and performance, wooden funereal figures called kkokdu, and golden royal crowns, extend his desire to elevate and preserve elements of Korean history. “His images do not simply document cultural heritage,” noted Sujong Song, of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. “They reanimate it, inviting viewers to reconsider the resonance of history in the here and now.”

Advertisement

googletag.cmd.push(function () {

googletag.display('div-gpt-ad-1343857479665-0');

});

On a more workaday level, Koo has photographed the colorful oval nubs of his almost finished soap bars, presenting them as typological grids, marking his own passage of time. Most he retrieved from his own bathroom, but, as a preternatural collector, he acquired others from café restrooms around town. “I am very interested in surface texture,” he said. “Photography and objects both keep time.” Lately, Koo is thinking about photographing Roman and medieval armor helmets: “They attract me a lot. I would like to catch the sweat and the agony of the soldiers who wore them.” He is also at work on a new book, revisiting those early pictures made in Europe at the start of his career, when he roamed the streets of Venice, London, Hamburg, and other cities with a 35mm camera. This editing process has been a means of conversing with his past self, and he has been pleased to discover the continuity, across half a century, of his search for the hidden and quietly surreal in the everyday.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 260, “The Seoul Issue.”

Aperture's Blog

- Aperture's profile

- 21 followers